Mimarlık, genellikle tarihin büyük dönüşümlerini takip eden dalgalar halinde ilerler: savaşlar, ekonomik patlamalar, teknolojik atılımlar ve kültürel değişimler. 1950’ler, İkinci Dünya Savaşı’ndan sonraki ilk tam on yıl olarak, her yerdeki mimarlar, planlamacılar ve hükümetlerin aynı acil soruyu yanıtlamak zorunda kaldığı bir dönemdir: Şehirleri, evleri ve kamusal yaşamı hızlı, uygun maliyetli ve yeni fikirlerle nasıl yeniden inşa edebiliriz? Bu baskı, bugün hala şehir silüetlerimizi şekillendiren tasarım dilleri ve inşaat yöntemlerinin ortaya çıkmasına neden oldu: işlevsellik ve netliğe daha güçlü bir inanç (Uluslararası Stil), toplu konut sistemleri ve prefabrikasyon denemeleri ve hem modern hem de gerekli görülen beton ve camın kamusal kullanımları. Bu unsurlar — aciliyet, standardizasyon ve daha iyi bir yaşam için ahlaki talep — 1950’li yılları tanımlar ve sonraki on yılların tonunu belirler.

1950’ler: Savaş Sonrası Pragmatizm ve Modernizmin Yükselişi

Küresel Bağlam: Yıkımın Ardından Yeniden İnşa

1950’ler stilistik kaprislerle değil, acil yeniden yapılanma ile şekillendi. Avrupa ve Asya’nın büyük bir kısmındaki şehirler fiziksel ve ekonomik olarak harap olmuştu; hükümetler hızlı bir şekilde konut, altyapı ve yeni kamu binalarına ihtiyaç duyuyordu. Bu aciliyet, rasyonelleştirilebilen ve ölçeklendirilebilen yaklaşımları destekledi: sistematik planlama, standartlaştırılmış bileşenler ve betonarme ve çeliğin yaygın kullanımı. Savaş öncesinde modern fikirleri savunan mimarlar, artık bunları büyük ölçekte uygulamak için resmi görevler ve devasa sosyal projeler buldular. Bu savaş sonrası durum, bir zamanlar avant-garde çevrelerin alanı olan modernist ilkelerin küresel yayılmasını hızlandırdı.

İnsan ve siyasi çıkarlar, mimariyi bir formdan daha fazlası haline getirdi: mimari, sosyal politikanın bir aracı haline geldi. Konut sıkıntısı, ulusal ve belediye yönetimlerini on yıllar yerine birkaç yıl içinde bütün mahalleler inşa etmeye itti; ekonomik kısıtlamalar ise tasarımcıları verimlilik ve tekrarlanabilirlik yönünde zorladı. Sovyet bloğu ve Batı Avrupa’da bu durum, aynı teknik çözümün farklı siyasi varyasyonlarına yol açtı: Doğu Avrupa’da büyük panel prefabrikasyon, Batı’da ise prefabrikler, belediye konutları ve yüksek katlı sosyal konutların bir karışımı. Her ikisi de özel yapım zanaatkarlıktan çok hız ve ölçeği hedefliyordu.

Uluslararası Tarzın Doğuşu

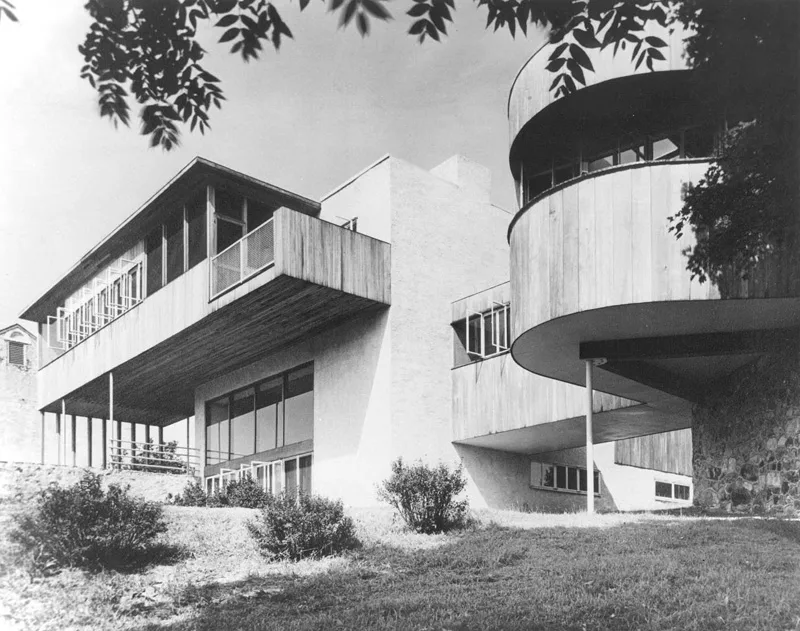

1930’larda Philip Johnson ve Henry-Russell Hitchcock tarafından isimlendirilen ve kanonize edilen Uluslararası Stil, biçimsel netliği ve yeni malzemelere olan güveni yeniden yapılanma dönemine uygun olduğu için savaş sonrası dönemde kitlesel görünürlük kazandı. Bu stilin ayırt edici özellikleri düz yüzeyler, minimal süslemeler, cam perde duvarlar ve yapının ve işlevin görünümü belirlemesi gerektiği inancıdır. 1950’lerde bu dil sadece estetik değildi: birçok ülkede ofisler, okullar, hastaneler ve konutlar hızlı ve anlaşılır bir şekilde üretmek için pratik bir araçtı. Müzeler, şirketler ve hükümetler, ölçülü ve anonim görünümü modern yaşamın ileriye dönük bir sembolü olarak benimsedi.

Ancak Uluslararası Stil tek ve tek tip bir sonuç değildi. 1950’lerde bölgesel özellikler taşıyan biçimlere dönüştü: Kuzey Avrupa’daki bazı binaların sıcak tuğla ve insancıl oranları, Güney Avrupa ve Latin Amerika’daki betonarme heykelsi denemeler ve büyüyen Amerikan şehir merkezlerindeki pragmatik cam ve çelik kuleler. En önemli olan, rasyonel düzene, standart detaylara ve malzemelerin dürüst ifadesine olan temel inançtı.

Önemli Mimarlar ve İmza Eserleri

1950’lerin bazı mimarları, savaş öncesinde de aktif olarak çalışıyorlardı ve artık daha geniş platformlarda yer alıyorlardı. Le Corbusier’in sosyal konut deneyimleri, Marsilya’daki Unité d’Habitation’da (1947-1952) somutlaştı. Bu, apartmanlar ve ortak tesislerden oluşan dikey bir “şehir”di ve hem bir prototip hem de savaş sonrası yaşam için tartışmalı bir model haline geldi. Projenin ölçeği ve programı, savaş sonrası kolektif yaşam ve mimarların ahlaki sorumlulukları hakkındaki tartışmalar için bir mihenk taşı haline geldi.

Aynı zamanda, bu on yıl, zorlu dersler veren sembolik başarısızlıklara da sahne oldu. St. Louis’deki Pruitt-Igoe konut kompleksi (1950’lerin ortasında tamamlandı), başlangıçta modern sosyal konut olarak övgüyle karşılandı, ancak hızla bozuldu ve 1972’de yıkılmasıyla ün kazandı; bu kompleksin kaderi, uzun vadeli bakım ve yerel bağlamdan kopuk, yukarıdan aşağıya planlama ve teknik çözümlerin istenmeyen sosyal sonuçlarının simgesi haline geldi. Pruitt-Igoe’nin hikayesi, mimarları ve planlamacıları tasarım, politika ve sosyal sistemlerin nasıl birbirine bağlı olduğu ile yüzleşmeye zorladı.

Dönemin Malzemeleri ve İnşaat Teknikleri

Betonarme, çelik iskelet ve cam perde duvarlar, 1950’lerin teknik terimleridir. Beton, hız, yapısal esneklik ve maliyet verimliliği sağladı; otoyol köprülerinden apartman bloklarına kadar daha uzun açıklıklar ve yeni bina tipleri mümkün kıldı. İngiltere’deki ahşap kit evler veya Orta ve Doğu Avrupa’daki büyük beton panel sistemleri gibi prefabrikasyon, malzeme kıtlığı ve işgücü kısıtlamalarına karşı ana akım bir çözüm haline geldi. Bu teknikler estetik sonuçlar da doğurdu: açıkta kalan beton ve modüler tekrarlar, on yılın karakteristik görünümleri haline geldi.

İnşaat teknikleri de bu süreçte gelişti: elemanların fabrika üretimi, şantiyede montaj iş akışları ve standart detayların kodlanması, vasıflı işgücü ihtiyacını azalttı ve teslimatı hızlandırdı. Bunun karşılığında, daha hızlı teslimat ve daha düşük birim maliyet, daha az özelleştirme ve çoğu durumda, ancak on ya da yirmi yıl sonra ortaya çıkan uzun vadeli bakım sorunları vardı. 1950’lerin teknik iyimserliği, böylece dayanıklılık, kullanıcı ihtiyaçları ve yenileme konusunda daha sonra ortaya çıkan tartışmaların tohumlarını içermekteydi.

Sosyal Konut ve Kentsel Projeler

Sosyal konutlar, 1950’lerin kamu mimarisi gündemini domine etti. Hükümetler, bombalanmış gecekondu mahallelerinin yerine geçmek veya savaş sonrası hızla artan nüfusu barındırmak için tasarlanmış büyük siteler, çok katlı bloklar ve bütün mahalleler inşa etmek için fon sağladı. Le Corbusier’in Unité modeli, İngiltere’deki belediye prefabrikleri ve Sovyetler Birliği’ndeki kitlesel panel sistemleri, bu siyasi iradenin ifadesidir: konut, kamu sorumluluğu; mimari ise kamu aracıdır. Bu projelerin başarısı, finansmanın sürekliliği, yerel yönetim ve planlamacıların günlük yaşamı tasarımlarına ne kadar iyi dahil ettiklerine bağlı olarak büyük farklılıklar gösterdi.

1950’lerden alınan gerçek hayattan dersler bugün de geçerliliğini korumaktadır. Yatırım ve sivil bakımın sürekli olduğu yerlerde, birçok savaş sonrası konut projesi uzun ömürlü mahalleler haline gelmiştir; bakım, topluluk katkısı veya sosyal hizmetlerin yetersiz olduğu yerlerde ise, başlangıçta ilerici niyetlere rağmen binalar çöküşe geçmiştir. 1950’ler bize açık bir ders vermektedir: ölçek ve teknoloji hızlı bir şekilde çok sayıda barınak sağlayabilir, ancak sosyal altyapı ve uzun vadeli yönetim, konutları zaman içinde insancıl hale getiren unsurlardır.

1960’lar: Ütopik Hayaller ve Acımasız Gerçekler

Kentsel Formda Deneyimleme Ruhu

1960’lar, şehirlerin tamamının modern yaşam için tutarlı makineler olarak yeniden tasarlanabileceğine inanan planlamacılar ve mimarlarla başladı. Brezilya’da, 1960 yılında Brasília’nın açılışı bu inancı ulusal ölçekte görünür kıldı: Lúcio Costa tarafından tasarlanan ve Oscar Niemeyer tarafından inşa edilen yepyeni bir başkent, caddeler, bakanlıklar, konut blokları ve peyzajların tek bir vizyon olarak işlediği toplam bir tasarım olarak tasarlandı. Katılıklarını takdir etseniz de eleştirseniz de, Brasília, verimlilik, sembolizm ve hız vaat eden kentsel deneyimlere olan on yıllık ilgiyi belirledi.

İnşa edilen başkentlerin yanı sıra, şehir kavramını yeniden şekillendiren spekülatif planlar da ortaya çıktı. Tokyo’da Kenzō Tange, büyümeyi karşılamak için körfezi aşan doğrusal bir mega yapı önerdi. Bu, modernist sistemleri Japon duyarlılığıyla birleştiren, radyalden genişletilebilir kentsel forma cesur bir geçişti. İnşa edilmemiş olsalar bile, bu öneriler önemliydi çünkü şehri tasarlanabilir, geliştirilebilir bir organizma olarak ele alıyorlardı ve bu, on yılın temel kentsel metaforu haline geldi.

Brutalizm: Felsefe, Biçim ve Tepki

1950’ler modernizmi normalleştirdiyse, 1960’lar onun en ham hali olan Brutalizm’i kamusal ve politik hale getirdi. Reyner Banham gibi eleştirmenler tarafından savunulan ve Team 10 ile bağlantılı mimarlar tarafından keşfedilen Brutalizm, “malzemelerin gerçeği”, yapının okunabilirliği ve sosyal amacı sadece bir görünüm olarak değil, etik olarak çerçeveledi. Pürüzlü beton, vurgulu kütle ve katmanlı sirkülasyona sahip binalar, özellikle üniversiteler ve hükümet için netlik ve sivil ciddiyet vaat ediyordu. Bu etik iddia, bu on yılda bu tarzın neden bu kadar yaygınlaştığını anlamak için çok önemlidir.

Aynı özellikler hızlı bir tepkiyi tetikledi. Betonun aşınması, bakımın gecikmesi ve yukarıdan aşağıya yenileme bürokrasiye dönüşmesiyle, Brutalist eserler, iddiaları cömert olsa bile, caydırıcı veya kentsel karşıtı olarak nitelendirildi. Boston Belediye Binası’nın şiddetli tartışmaları bu dönüşümü yansıtıyor: şeffaf bir sivil düzenin ifadesi olarak tasarlanan bina, o günden bu yana övgü ve eleştiri döngüsüne maruz kalıyor. Günümüzün yeniden değerlendirmeleri, sarkacın tekrar sallandığını gösteriyor — eleştiriler ortadan kalkmadı, ancak yeni nesil betonun ardındaki kamusal hırsı fark ediyor.

Megastrüktürler ve Modüler Konseptler

1960’ların hayal gücü, yaşamın takılabileceği, değiştirilebileceği ve büyüyebileceği devasa yapılar olan megastrüktürlerden daha fazla hiçbir yerde bu kadar ateşli değildi. Archigram’ın Plug-In City projesi, konut, hizmet ve mobilite birimlerinin vinçlerle kaldırılıp değiştirildiği bir altyapı iskeleti hayal ediyordu; bu şehir, sabit bir formdan ziyade yaşayan bir teknoloji platformu gibi ele alınıyordu. Bu imge pop, küstah ve hızla değişen dünyada uyum sağlama konusunda son derece ciddiydi.

Japonya’nın Metabolistler grubu, bu uyarlanabilirliğe biyolojik bir metafor kazandırdı. Tange’nin Tokyo Körfezi planı ve grubun projeleri, kapsüller, modüler hizmetler ve genişletilebilir omurgalar aracılığıyla kimliğini kaybetmeden parçalarını değiştiren, metabolize olan şehirler öneriyordu. Montreal’deki Habitat 67, Expo ’67’de istiflenebilir prefabrik birimlerin mantığını gerçek konutlara dönüştürerek, megastrüktür hayalini somut ve fotojenik hale getirdi. Bu çalışmalar, mimariyi büyüme, bakım ve yenilemeyi sonradan akla gelen fikirler olarak değil, temel tasarım eylemleri olarak hayal etmeye itti.

Mimarlık ve Sosyal Hareketler

1960’lar, vatandaşların planlamacılara karşı çıktıkları on yıl oldu. Jane Jacobs’un 1961 tarihli kitabı, günlük kentsel deneyimlere dil kazandırdı ve toplulukları yıkıcı yenileme planlarına ve şehir içi otoyollara karşı çıkmak için silahlandırdı. New York, San Francisco, Boston ve diğer şehirlerde yaşanan “otoyol isyanları”, iktidar, yerinden edilme ve verimliliğin gerçek maliyetleri konusunda hesaplaşmayı zorunlu kıldı. Mimarlık bir boşlukta gerçekleşmedi; sokaklarda, mahkemelerde ve mahalle toplantılarında tartışıldı.

Columbia’dan Japonya’daki üniversitelere kadar kampüs ve gençlik hareketleri, bu sürece bir başka boyut kattı. İşgal eylemleri, savaş karşıtı protestolar ve sivil haklar aktivizmi, kurumların mekan, güvenlik ve açıklık planlamalarını yeniden şekillendirdi. On yılın sonunda, Ian McHarg’ın Design with Nature (Doğa ile Tasarım) adlı eseriyle çevrecilik ortaya çıktı. Bu eser, ekolojik sistemler etrafında planlamayı yeniden çerçevelendirdi ve günümüzün peyzaj şehirciliği ve yeşil altyapısının temellerini attı. Sonuç olarak, mimarinin sadece müşterilere ve kurallara değil, aynı zamanda kamusal yaşama, siyasete ve gezegene de cevap vermesi gerektiği ortaya çıktı.

Önemli Projeler ve Küresel Etki

Binalarda on yılı görmek istiyorsanız, Tokyo’daki Yoyogi Ulusal Spor Salonu’ndan başlayın. Tange’nin 1964 Olimpiyatları için tamamladığı geniş kablo ile asılı çatı, yeni bir yapısal şiirsel ifadeyi somutlaştırdı: köprüler binalara dönüştü, mühendislik ulusal kimlik olarak kutlandı. Aynı 60’ların ortalarında, Louis Kahn’ın La Jolla’daki Salk Enstitüsü, anıtsal sükuneti bilime adanmış bir mekana dönüştürdü; titiz bir yapı ile Pasifik’e uzanan ince bir dere ile kesilmiş, düşüncelere daldırıcı bir avluyu bir araya getirdi. Bunlar sadece formlar değildi; kamu kurumlarının nasıl hissedilebileceğine dair argümanlardı.

Sivil alanda, Boston Belediye Binası brutalizmi belediye yaşamının merkezine taşıdı, Expo ’67 ise Habitat 67’de modüler konutları bir gösteri olarak sergiledi ve jeodezik ABD Pavyonu mühendisliği göz alıcı hale getirdi. Atlantik ve Amerika kıtalarında, 1960’ların imgeleri ve tartışmaları dışa yayıldı: sıfırdan planlanan başkentler, stüdyolara asılan mega yapı çizimleri, hızla yükselen beton kampüsler. Küresel ders iki yönlüydü: mimari, kentsel ölçekte yeni dünyalar çizebilirdi, ancak bu dünyalar ancak sürdürülebilir, sevilen ve içinde yaşayan insanlara karşı sorumlu olmaları halinde gelişebilirdi.

1970’ler: Kriz, Ekoloji ve Karşı Kültür Estetiği

Ekonomik Durgunluk ve Mimari Kemer Sıkma

On yıl, petrol şokları ve stagflasyonun gölgesinde başlıyor ve bunu mimarların masalarına gelen özetlerde hissedebiliyorsunuz. Enerji birdenbire gerçek paraya mal oluyor, enflasyon bütçeleri eritiyor ve kamu işleri duruyor ya da değer mühendisliğine tabi tutuluyor. İngiltere’de “Üç Günlük Hafta” ve sürekli elektrik kesintileri kısıtlamayı somut hale getirirken, OECD raporları sanayi dünyasındaki enflasyon ve yavaşlayan büyüme konusunda endişe duyuyor. Ruh hali genişlemeden tasarrufa doğru değişiyor: daha az büyük jestler, daha dikkatli zarflar, işletme maliyetlerine ve aydınlatma yüklerine daha fazla dikkat. Mimarlık, enerjiyi sadece bir fatura olarak değil, bir tasarım malzemesi olarak ele almaya başlıyor.

Sonuçlar ilk olarak binaların içinde ortaya çıkıyor. Bir zamanlar tek tip floresan tavanlarla parıldayan ofisler lambalarını dökmeye başlıyor; tasarımcılar gün ışığını ve görev aydınlatmasını eski moda ideallerden ziyade performans stratejileri olarak yeniden keşfediyor. On yılın sonunda, ekonomik tahminlerde bile inşaat sektörünün zayıfladığı belirtiliyor ve mimarlar, yerel yönetimleri ve uygulamaları neyin nasıl inşa edilebileceğini yeniden düşünmeye zorlayan bir “kriz” hakkında açıkça konuşuyor. Daha yalın, daha taktiksel bir mimari ortaya çıkıyor; bu mimari, bina kabuğunun performansını, aşamalı teslimatı ve şehirlerin halihazırda sahip olduğu şeylerin yeniden kullanımını ön plana çıkarıyor.

Yüksek Teknolojili Mimarinin Yükselişi

Bu tutumluluğa karşı, farklı bir iyimserlik ortaya çıkıyor: binanın içini gösterin, yapıyı ve hizmetleri mimariye dönüştürün ve uyarlanabilirlik için tasarım yapın. Bu fikir, 1977’de Paris’teki Centre Pompidou’da birleşiyor. Bu bina, sirkülasyonu ve kanalları renk kodlu bir dış iskelete dönüştürüyor ve müzeyi bir kamu makinesi olarak yeniden şekillendiriyor. Anında tartışmalı ve anında çekici olan bu bina, karşı kültür ethosunu titiz mühendislikle birleştiriyor.

İngiltere’de dil, disiplinli bir zanaat olarak olgunlaşır. Norman Foster’ın 1978 yılında tamamladığı Sainsbury Görsel Sanatlar Merkezi, yapı ve hizmetleri ince, hizmet verilen bir kabuğun içine yerleştirerek galeriler, öğretim ve sosyal yaşam için tek ve esnek bir oda yaratır. Richard Rogers, 1978 yılında tamamlanan Lloyd’s of London’da “içten dışa” mantığını daha da ileri götürür. Burada merdivenler, asansörler ve tesisler, merkezdeki uyarlanabilir ticaret salonunu serbest bırakmak için çevreye taşınır. High-Tech’in vaadi dekorasyon değil, değişim yoluyla uzun ömürlülüktür; binalar sabit nesnelerden ziyade yükseltilebilir çerçevelerdir.

Yeşil Başlangıçlar: Erken Sürdürülebilir Tasarım

Enerji şokları sadece ışıkları kısmakla kalmaz, aynı zamanda bir araştırma kültürünü de tetikler. Mimarlar ve mühendisler süper yalıtım, hava sızdırmazlığı ve ısı geri kazanımlı havalandırmayı test etmeye başlar ve soruyu “nasıl daha fazla enerji ekleyebiliriz”den “nasıl daha az enerjiye ihtiyaç duyabiliriz”e kaydırır. Illinois “Lo-Cal” House (1976) ve Saskatchewan Conservation House (1977) gibi prototipler, dikkatlice yalıtılmış, yüksek izolasyonlu bir dış cephe ile kontrollü taze hava değişiminin bir araya gelmesiyle ısıtma ihtiyacının geleneksel talebin çok altına düşebileceğini göstermektedir. Bu küçük evler, onlarca yıl sonra yankı bulacak standartları ve uygulamaları besleyen büyük fikirler haline gelir.

Aynı zamanda, tasarım kültürü pasif güneş enerjisi bilgisini ve iklime duyarlı formları benimser. Edward Mazria’nın 1979 tarihli kitabı, pratik kuralları, güneş açısı çizelgelerini ve sistem türlerini bir araya getirerek, bir nesil uygulayıcının gadget’lar yerine yönelim, kütle ve gölgeleme konusunda düşünmesine yardımcı olur. ABD, 1977’de Enerji Bakanlığı’nı kurarak, performansın niş bir hobi değil, ulusal bir proje olacağını işaret eder. Acil durum müdahalesi olarak başlayan şey, günümüzün net sıfır ve pasif bina hareketlerinin tohum yatağı olan bir yöntem haline gelmiştir.

4 Ağustos 1977: Başkan Carter, Enerji Bakanlığı Teşkilat Kanunu’nu imzalar.

Eleştirel Bölgeselcilik ve Kültürel Kimlik

Bir kesim evrensel teknolojiyi kutlarken, diğer kesim binaların pastişe kaçmadan bulundukları yere nasıl ait olabileceğini sorguluyor. Bu teori, 1980’lerin başında Alexander Tzonis, Liane Lefaivre ve Kenneth Frampton tarafından isimlendirilecek, ancak 1970’lerde atılan temelleri şimdiden görülebilir: iklim, zanaat ve yerel kültürle şekillenen modern mimari. Bu argüman nostalji değil; yerellikten uzaklaşmaya karşı ölçülü bir direniş, modernliğin yerel bir aksanla konuşması için yapılan bir çağrıdır.

Küresel Güney’deki uygulamalar bunun nasıl yapılabileceğini gösteriyor. Hassan Fathy’nin 1969 yılında yayınlanan ve çok okunan kitabı, toprak yapılar, avlular ve pasif soğutmayı modern bir sosyal projeye dönüştürürken, Sri Lanka’lı Geoffrey Bawa, çağdaş planlama ile muson yağmurlarına hazır bölümler, gölgeli verandalar ve gözenekli kenarları sessizce radikal bir şekilde harmanlayan “tropikal modernizm”i geliştiriyor. On yılın sonunda, Balkrishna Doshi ve meslektaşları gibi Hintli mimarlar da benzer melezler geliştirerek, bağlamsal zekanın dar görüşlü olmaktan ziyade ilerici olabileceğini kanıtlamışlardır.

Kentsel Çürüme ve Uyarlanabilir Yeniden Kullanım

Fabrikalar kapanıp vergi gelirleri azaldıkça, birçok şehir zor günler yaşamaya başlar. New York’un 1975 mali krizi, belediye tasarrufları ve kentsel istikrarsızlığın sembolü haline gelirken, kullanılmayan depolar ve pazarlarla dolu mahalleler atıl kalır. Ancak bu gerileme, yeni bir yaklaşımı da beraberinde getirir: Mevcut olanı yeniden kullanmak, karma programlar düzenlemek ve mega projeler yerine küçük adımlarla kamusal yaşamı yeniden inşa etmek. Boston’da, 19. yüzyıldan kalma Quincy Market, 1976’da Faneuil Hall Marketplace olarak yeniden açılır. Uzun hangarları onarılır ve canlı bir “festival pazarı”na dönüştürülür. Bu, korumanın muhafazakar değil, katalizör olabileceğini gösterir.

New York’ta, 1960’ların sonlarında ve 1970’lerde sanatçıların SoHo loftlarını işgal etmeleri, yasal imar çerçeveleri ve endüstriyel alanların konut alanlarına dönüştürülmesine yönelik kalıcı bir modele dönüşmüştür. Hayatta kalmak için başlayan bu süreç —ucuz alan, geniş katlar, iyi ışık— daha sonra dünyanın dört bir yanındaki şehirlerin uyarlayacağı bir kentsel gelişim senaryosuna dönüştü. 1970’lerdeki uyarlanabilir yeniden kullanım, doktriner olmaktan çok pragmatik bir yaklaşımdı: somut enerji tasarrufu, karakterin korunması ve sokakları zaten tanıyan binalara sivil yaşamın yeniden kazandırılması.

1980’ler: Postmodernizmin Cesur Renkleri ve İronileri

Modernizmden Postmodern Neşeliye

1980’lerin havası kostüm değişikliği gibi gelir: On yıllar süren sade modernizmden sonra, mimarlar renk, alıntı ve zekâya adım atarlar. Önemli bir dönüm noktası, 1980 Venedik Bienali sergisi “Geçmişin Varlığı”dır. Burada Robert Venturi’den Ricardo Bofill’e kadar birçok isim, klasik anıları çağdaş ihtiyaçlarla harmanlayan binalar sunar. Mesaj basit ama yıkıcıdır: tarih bir yük değil, bir araç kutusudur. Süslemeler geri döner, cepheler yeniden konuşur ve binalar tarafsızlığın arkasına saklanmak yerine sembolizmle flört eder.

Bu değişim sadece görsel değildir. Entelektüel ve kültürel bir değişimdir ve tek bir evrensel dilin her yere uyması gerektiği fikrine karşı çıkmaktadır. Postmodern mimari, şehirleri anlamların dokumaları olarak ele alır; burada kırık bir alınlık veya bir renk sıçraması yerel referanslar, mizah ve eleştiri taşıyabilir. On yılın tonu kasıtlı olarak çoğuldur: birçok ses, birçok kelime dağarcığı ve artık kitle iletişim araçları ve tüketim kültürünü de içeren bir izleyici kitlesi önünde binaların ironik bir şekilde performans sergilemesine izin verme isteği.

Mimari Dil ve Tarihsel Referans

Modernizm soyutlamayı önemserken, 1980’ler kelimeleri ve grameri geri getirir. Venturi ve Denise Scott Brown’ın Las Vegas çalışmaları, sokak için yeni bir sözlük sunarak, kelimenin tam anlamıyla “ördek” ile pragmatik “süslenmiş kulübe”yi birbirinden ayırır. Bu ayrım, tasarımcılara tabelaları, yüzeyleri ve uygulanan motifleri gizlenmesi gereken günahlar olarak değil, meşru iletişim biçimleri olarak ele alma izni verir. Bir cephe sahte olmadan alıntı yapabilir; bir çatı hattı manşet haline gelebilir.

Bu dil, gökdelen ölçeğinde ortaya çıkıyor. Philip Johnson’ın AT&T Binası (şimdiki adı 550 Madison), granit bir kulenin tepesini devasa bir Chippendale tarzı kırık alınlık ile taçlandırıyor ve Manhattan’ın merkezine eğlenceli bir klasik selam gönderiyor. Bu hareket hem teatral hem de ciddidir — kurumsal mimarinin sadece şık bir tarafsızlık değil, kültürel hafızayı da taşıyabileceği argümanıdır. Bofill farklı bir geçmişe uzanır ve Barok ölçeğinde eksenler ve zafer kemerlerini Les Espaces d’Abraxas’taki sosyal konutlara aktarır, burada anıtsallık günlük yaşamı çerçeveler.

Kurumsal Gökdelenler ve Tüketimcilik

On yılın kurumsal ikonları, markalaşmayı mimari olarak anlıyor. AT&T, Johnson ve Burgee’nin tasarımını açıkladığında, bu haber manşetlere taşındı ve anında “postmodern gökdelen” olarak adlandırıldı. Bu, bir genel merkezin reklam kampanyası kadar net bir şekilde sembollerle konuşabileceğinin kanıtıydı. Granit, alınlıklar ve büyük boyutlu detaylar, silüette tanınabilir bir görüntü oluşturdu: üç boyutlu bir logo. Bu görünürlük, daha sonra yenileme ve koruma konusunda şiddetli tartışmalara yol açtı ve binanın kamuoyunun bilincine ne kadar güçlü bir şekilde girdiğini vurguladı.

Tüketici kültürü, ürün ve binayı birbirine karıştırır. Michael Graves, postmodern paleti cephelerden su ısıtıcılarına taşır: 1985 yılında Alessi için tasarladığı 9093 çaydanlık, kitlesel pazarda büyük bir başarı elde eder ve aynı eğlenceli dilin hem ocak başında hem de şehir bloklarında nasıl yaşayabileceğini gösterir. Bu geçiş önemlidir. Postmodernizmin neden sadece profesyonel bir tartışma değil, geniş bir yaşam tarzı değişikliği gibi hissedildiğini gösterir: kurumsal lobileri, müze atriyumları ve ev eşyaları, hepsi aynı parlak, referanslı tonda konuşmaya başlar.

Önemli Kişiler: Venturi, Graves ve Bofill

Venturi (Denise Scott Brown ile birlikte) bu on yıla teorik bir temel kazandırır. Las Vegas’tan Öğrenmek, şehri sembolizm ve günlük ticaretin otantik kentsel ipuçları ürettiği, okunabilir bir manzara olarak yeniden çerçeveler. Uygulamada, onların yaklaşımı okunabilir planları, iletişimsel cepheleri ve sıradanlığa olan rahatlığı tercih eder; bu, katı evrenselciliğin panzehiri gibidir. Onların fikirleri 1980’lerde stüdyolara ve planlama departmanlarına sızarak, izleyicileri kendilerini açıklarken gülümseyen binaları takdir etmeye hazırlar.

Graves, hareketin kamuoyundaki yüzü olur. 1982 yılında tamamlanan Portland Binası, mütevazı bir ofis kulesini cesur renk blokları, kilit taşları ve dev çelenklerle sararak, belediye işyerini bir sivil poster haline getirir. Aynı duyarlılık, Alessi ürünlerinde de kendini gösterir ve tasarım müzesini hiç ziyaret etmemiş milyonlarca insana postmodern motifleri tanıtır. Sevgi ve tepki eşit ölçüde gelir, ancak bu çalışma, sıcaklık, mizah ve tarihin kurumsal programları ve günlük ürünleri aynı şekilde taşıyabileceğini kanıtlar.

Bofill, dili kentsel dramaya taşıyor. Paris dışındaki Les Espaces d’Abraxas’ta, ekibi klasik parçalardan (saray, kemer, tiyatro) oluşan bir sosyal konut sahne dekoru oluşturuyor ve bunları modern malzemelerle yeniden şekillendiriyor. Sonuç sinematik ve tartışmalı, ancak inkar edilemez bir şekilde etkileyici; bir film arka planı ve anıtsallık ve hafızanın sıradan konutlara nasıl hizmet edebileceğini araştıran tasarımcılar için bir referans noktası haline geliyor.

Tepkiler ve Eleştiriler

On yılın ortasına gelindiğinde, parti eleştirilerle karşılaşır. Bazı gözlemciler, yüzeysel sembolizmin zayıf performansı maskelediğini ve birkaç yüksek profilli binanın dış cephe kaplaması ve bakımıyla ilgili sorunlar yaşadığını savunur. Portland’ın simgesel belediye kulesi, on yıllar sonra önemli bir dış cephe kaplaması yenilemesine ihtiyaç duyar ve ifade gücü yüksek dış cephe kaplamalarının dayanıklılık, nem ve enerji gibi zorlu gerçeklerle nasıl başa çıkması gerektiğine dair bir vaka çalışması haline gelir. Buradan çıkarılacak ders, oyun oynamanın yanlış olduğu değil, performansın sonradan akla gelen bir şey olamayacağıdır.

Entelektüel açıdan da rüzgar yön değiştirir. 1988’de MoMA’nın “Dekonstrüktivist Mimari” sergisi, postmodern tarihçiliği karmaşık bir dünya için fazla düzenli bulan, daha az ironik, daha parçalı yeni bir akımı bir araya getirir. Bu arada, 550 Madison’ın değiştirilmesine ilişkin tartışmalar protestolara ve nihayetinde tarihi eser koruma statüsüne yol açar, bu da hareketin en teatral eserlerinin bile şehrin kültürel hafızasının bir parçası haline geldiğini gösterir. Postmodernizm, hem sorgulanmış hem de kanonize edilmiş olarak on yılı sonlandırır: yüzeyselliği nedeniyle eleştirilirken, önemi nedeniyle korunur.

1990’lar: Küreselleşme, Dekonstrüktivizm ve Dijital Başlangıçlar

Dekonstrüktivizm ve Parçalanmış Formlar

1990’lar, mimarların önceki teorileri inşa edilmiş deneyimlere dönüştürmesiyle başladı. MoMA’nın 1988 tarihli “Dekonstrüktivist Mimari” sergisi etrafında bir araya gelen fikirler — parçalanmış geometri, dinamik yüzeyler ve klasik düzeni bozma isteği — çizimlerden ve manifestolardan beton ve çeliğe dönüştü. Bu dönüşümü, Zaha Hadid’in tamamladığı ilk bina olan Vitra İtfaiye İstasyonu’nda (1993) hissedebilirsiniz. Bu bina, hareketin ortasında donmuş gibi görünen kesik düzlemlerden oluşan gergin bir kompozisyondur. On yılın sonunda, Daniel Libeskind’in Berlin’deki zikzaklı Yahudi Müzesi, boşluklar, keskin kesikler ve kafa karıştırıcı yollar kullanarak yokluğu ve hafızayı somutlaştırarak köşeli formu kültürel bir anlatıya dönüştürdü. Bu eserler birlikte, mimarinin hem soyut hem de duygusal olabileceğini ve yeni formların karmaşık kamusal hikayeleri taşıyabileceğini gösterdi.

Dil yayıldıkça, “decon” bir etiket olmaktan çıkıp bir araç setine dönüştü. Mimarlar, kırık çizgilerle dolaşımı koreografik hale getirdiler, birleştirilmiş hacimlerle ışığı sahnelediler ve eğimli duvarlarla bedenin uzay algısını yoğunlaştırdılar. Amaç, sırf şok etmek değildi; algıyı yeniden aktif hale getirmekti. Ziyaretçiler bu binalara sadece bakmakla kalmadılar, onları izlediler, kenarlarında yürüdüler ve kenarlarının geri ittiğini hissettiler. 1990’lar, bu stilin hızlandırıcı etkisini kaybetmeden sivil ölçekte inşa edilebileceğini kanıtladı.

Küresel Simgeler ve Marka Mimarisi

Guggenheim Bilbao Müzesi (1997) kadar, on yılın küresel hayal gücünü şekillendiren başka bir proje yoktu. Frank Gehry’nin titanyum kıvrımları, Bask şehrine çekici bir siluet kazandırdı ve kültürel yatırım ile gerçekten farklı bir mimarinin turizmi ve ekonomik yenilenmeyi katalize edebileceği fikrini ifade eden “Bilbao etkisi”nin ortaya çıkmasına yardımcı oldu. O zamandan beri yapılan analizler, bölgede önemli bir etki yarattığını ölçerken, Bilbao’nun başarısının sadece şekle değil, dikkatli yönetişim, altyapı ve programlamaya bağlı olduğunu da vurguladı. Her halükarda, Bilbao bir müzenin bir şehir için neler yapabileceği ve bir imajın ne kadar hızlı bir şekilde dünyaya yayılabileceği konusundaki beklentileri yeniden belirledi.

Simgesel yarış sadece müzelerle sınırlı değildi. Ulusal ve kurumsal markalar, süper yüksek kuleler ve yeni nesil terminallerle yükselişe geçti: Petronas Kuleleri (1998’de tamamlandı) kısa bir süreliğine dünyanın en yüksek binası unvanını aldı ve Malezya’nın modernliğini dünyaya duyurdu; Hong Kong’un Chek Lap Kok Havalimanı (1998’de açıldı) tek bir yüksek salonda küresel bir hub’ı barındırdı; Şangay’ın Pudong silüeti, Jin Mao Kulesi (1999) ve Oriental Pearl Kulesi (1994/95) gibi simgesel yapılarla hızla şekillendi. Bu yapılar, kentsel ölçekte logolar gibi işlev gördü — anında okunabilir, medyaya hazır ve yeni ticaret akışlarıyla bağlantılıydı.

Ünlü mimarlar ve imza tasarımın yükselişi

İkonlar çoğaldıkça, medya yeni bir terim icat etti: “starchitect” (yıldız mimar). Sözlükler ve eleştirmenler, bu terimi, şöhreti ve tanınırlığı mesleğinin çok ötesine ulaşan tasarımcıları tanımlamak için kullandılar. Ödüller bu ilgiyi daha da güçlendirdi — 1990’larda Pritzker Ödülü, Tadao Ando (1995), Renzo Piano (1998) ve Norman Foster (1999) gibi isimlere verildi ve kalite ve ilgi garantisi olarak kabul edilen, küresel çapta faaliyet gösteren mimarların kanonunu pekiştirdi. Bu etiket her zaman tartışmalı olmuştur, ancak gerçek bir pazar mantığını yansıtıyordu: şehirler ve müşteriler, bir ismin fark yaratabileceğine inanıyordu.

Gehry’nin Bilbao’dan sonra ani şöhreti, bu dinamikleri daha da belirgin hale getirdi. Anketler ve haberler onu neslinin dönüm noktası olarak gösterdi ve tartışma, imza niteliğindeki tasarımların kültürü zenginleştirip zenginleştirmediği ya da sadece gösteriş peşinde olup olmadığına kadar genişledi. Bu şöhret çerçevesinin içinde bile, önde gelen mimarlar kamu değeri ve uzun vadeli performansın öncelikli olması gerektiğini savundu. Bu tartışma, bazı “ikonik” projelerin dengesiz bir şekilde eskimesiyle 2000’li yıllara kadar devam etti.

Dijital Araçlar Tasarım Sürecine Giriyor

Yeni silüetlerin arkasında yeni yazılımlar yatıyordu. 1990’ların ortasından sonlarına doğru, 3D modelleme ve animasyon araçları stüdyolardan günlük mimari iş akışlarına taşındı: 3D Studio MAX, 1996 yılında Windows için piyasaya sürüldü; Rhino 1.0, erişilebilir NURBS modelleme özelliği ile 1998’de piyasaya sürüldü; Greg Lynn’in Animate Form (1999) adlı kitabı ise tasarımcılara sürekli, dijital olarak yönlendirilen formlar için bir kelime dağarcığı sağladı. Bu araçlar, yinelemeyi, ışık ve yapıyı test etmeyi ve karmaşık geometri etrafında çizimleri koordine etmeyi kolaylaştırdı — bu, çizilebilecek, iletilebilecek ve inşa edilebilecek şeyleri değiştiren sessiz bir devrimdi.

Gehry’nin ofisi, havacılık platformu CATIA’yı uyarlayarak Bilbao’nun kıvrımlı dış cephelerini üretim düzeyinde hassasiyetle tasarlamak ve teslim etmek suretiyle sınırları zorladı. Bu hamle, daha sonra ortaya çıkan “tasarımdan üretime” iş akışlarının habercisi oldu ve mimariye özel CATIA tabanlı bir araç olan Digital Project’in doğmasına neden oldu. Birdenbire, mimarlar belirsizliği verilerle değiştirebilir, geometriyi doğrudan imalatçılara ve müteahhitlere gönderebilirler hale geldi. Sonuç sadece yeni şekiller değil, çizim ve üretim arasında yeni bir sözleşmeydi.

Küreselleşmiş Ekonomide Mimarlık

On yılın ekonomisi, bu alanı yazılım kadar şekillendirdi. 1 Ocak 1995’te faaliyete geçen Dünya Ticaret Örgütü, küresel ticaretin kurallara dayalı bir şekilde genişleyeceğinin sinyalini verdi; bunu özellikle Asya ve Orta Doğu’da sermaye, yetenek ve komisyonlar izledi. Şanghay’ın Pudong finans bölgesi 1990’ların başında hızlı bir gelişme için seçildi ve on yılın sonunda bu bölgenin silüeti Çin’in dünyaya açıldığını gösteriyordu. Mimarlık firmaları, uluslararası ekipleri yönetmeyi, uzak mesafeli yarışmaları kazanmayı ve marka duyarlılığı yüksek, medyaya uygun projeleri hızla teslim etmeyi öğrendi.

Ardından bir sarsıntı yaşandı: 1997-98 Asya finans krizi finansmanı dondurdu ve coşkulu planları alçaltarak müşterilere ve tasarımcılara ikonların hala iş döngülerinde yaşadığını hatırlattı. Devam eden projeler, maliyet, aşamalandırma ve esnekliğe daha fazla dikkat ederek ilerledi — bu alışkanlıklar, küresel rekabetin ve kamu-özel sektör ortaklıklarının patlamasıyla birlikte 2000’li yıllara da taşındı. Kısacası, 1990’lar daha geniş bir pazarı daha geniş bir araç setiyle birleştirerek, ardından gelen “ikon çağı”nın karışık nimetlerini oluşturdu.

2000’ler–2020’ler: İklim Krizi, Veri ve Yeni Materyalizm

Milenyumun başlangıcı, mimari öncelikleri yeniden şekillendirdi. Raporlar, binaların enerji kullanımını ve emisyonları ne kadar etkilediğini göstererek iklim biliminin arka plandaki bir unsur olmaktan çıkıp ana gündem maddesi haline gelmesini sağladı ve tasarımcıları, gösteriş için gösterişten ziyade düşük karbon performansı ve uyarlanabilir yeniden kullanım yönünde itti. 2020’lerin başından ortasına kadar, küresel değerlendirmeler açık sözlüydü: binalar ve inşaatlar, enerji talebinin yaklaşık üçte birinden ve enerji ve süreçle ilgili CO₂ emisyonlarının üçte birinden fazlasından sorumluydu ve ilerleme, Paris Anlaşması’nın gerektirdiği yolun gerisinde kalıyordu. Mimarlığın görev tanımı, formu şekillendirmekten ayak izini yeniden şekillendirmeye doğru genişledi.

Aynı zamanda, hesaplama bir arka ofis aracından stüdyo yardımcısına dönüştü. Yazılım, geometriyi fizikle birleştirdi; veri akışları ve dijital üretim, çizim ve üretim arasındaki sınırı bulanıklaştırdı. Kütle ahşaptan yarı saydam polimerlere kadar yeni malzemeler daha hafif yapılar ve daha düşük karbon salınımı sağlarken, düzenlemeler de bu malzemelerin eskisinden çok daha yüksek seviyelere çıkmasına izin vermeye başladı. Bu dönemin en iyi çalışmaları, tek bir kahramanca hareketten çok, daha çok bir orkestrasyonla ilgilidir: performans analitiği, tedarik zinciri seçimleri, kamusal alan onarımı ve insan sağlığı, ilk günden itibaren tasarıma dahil edildi.

Parametrikizm ve Algoritmik Tasarım

Parametrik düşünce, tasarımı canlı bir ilişki sistemi olarak tanımlar: pencere derinliğini değiştirin, gün ışığı değişsin; cephe desenini hafifçe değiştirin, enerji talebi buna yanıt versin. “Parametriklik” terimi 2000’lerin sonlarında gündeme geldi, ancak daha geniş kapsamlı uygulama kısa sürede bir manifesto olmaktan çıkıp bir yöntem haline geldi; modelleri analiz motorlarına bağlayarak form ve performansın birlikte gelişmesini sağladı. Rhino+Grasshopper gibi araç zincirleri ve Ladybug ve Honeybee gibi açık kaynaklı eklentiler, mimarların geometriyi tasarım ortamı içinde doğrulanmış gün ışığı ve enerji simülasyonlarına bağlamasına olanak tanıyarak iklim dosyalarını anında görsel geri bildirime dönüştürür.

Stüdyolarda ve dersliklerde, bu algoritmik döngü yinelemenin hissini değiştirdi. Tasarımcılar artık, manzarayı korurken parlamayı azaltan bir cephe veya soğutma yükünü azaltan bir merdiven çekirdeği konumu bulmak için düzinelerce varyasyon çalıştırıyor. Bu değişim teknik olduğu kadar kültürel de: kararlar, çizimlerin yanı sıra gösterge panelleriyle tartışılıyor ve “en iyi” sadece görünümle değil, hava, ışık ve konforla da test ediliyor.

Net Sıfır, Pasif Evler ve Yeşil Sertifikalar

Net sıfır, ABD Enerji Bakanlığı’nın 2015 yılında ortak bir tanım yayınlamasıyla moda sözcük olmaktan çıkıp çalışma hedefi haline geldi: kaynak enerji bazında, yıllık olarak kullandığı kadar yenilenebilir enerji üreten enerji verimli bir bina. Bu çerçeve kampüslere, portföylere ve topluluklara genişletildi, böylece sahiplerin hedefleri belirlemesi ve doğrulaması kolaylaştı. Buna paralel olarak, küresel raporlar bunun neden önemli olduğunu vurguladı: bina sektörünün enerji talebi ve emisyonları, yoğunluk hafifçe düşmesine rağmen 2022’de yeni zirvelere ulaştı; bu da hedeflerin ölçeğinin büyütülmesi gerektiğinin kanıtıdır.

Pasif Ev, farklı ama tamamlayıcı bir yol sundu: önce talebi azaltmak, sonra yenilenebilir enerji kaynaklarını eklemek. Birçok iklim için metrekare başına yıllık yaklaşık 15 kWh olan iyi bilinen ısıtma ve soğutma eşikleri, tasarımları hava sızdırmazlığı, sürekli yalıtım ve ısı geri kazanımlı havalandırma üzerine odaklamaktadır. Projeler, performansı doğrulamak için PHPP aracını kullanır ve bu titiz rakamları, küçük mekanik sistemlere sahip sessiz ve konforlu binalara dönüştürür. LEED, BREEAM, WELL ve Living Building Challenge gibi sertifikalar, malzeme şeffaflığı ve su kullanımından eşitlik ve güzelliğe kadar daha geniş sağlık ve sürdürülebilirlik ölçütlerini katmanlayarak müşteriler ve şehirler için ortak ölçütler oluşturur.

Dijital Üretim ve Akıllı Malzemeler

Tasarım mantığı makinelerle buluştuğunda, elle çizilemeyecek kadar karmaşık parçalar ve şekillerinin neden böyle olduğunu bilen montajlar ortaya çıkar. İsviçre’deki DFAB House, Empa’nın NEST araştırma binasına bağlı olarak, robotik şekillendirme, 3D baskılı kalıplar ve hesaplamalı levhaların, sadece prototip olarak değil, gerçekten yaşanabilir, daha hafif ve malzeme verimli yapılar üretebileceğini gösterdi. Amsterdam’da, bir sensör ağıyla “dijital ikiz” besleyen 3D baskılı çelik bir köprü açıldı, böylece mühendisler gerilme, titreşim ve kalabalık modellerini gerçek zamanlı olarak takip edebiliyorlar — tahmin yerine ölçüm yoluyla bakım yapabiliyorlar.

Malzeme paletleri de genişledi. Münih’teki Allianz Arena’da kullanılan ETFE yastık cepheler, camın ağırlığının çok altında bir ağırlıkla olağanüstü ışık geçirgenliği sağlar ve daha az destek çeliği ile ışık saçan cepheler oluşturur. Diğer yandan, çapraz lamine ahşap (CLT) gibi “yeni geleneksel” malzemeler, yönetmelik değişiklikleriyle olgunlaştı: 2021 Uluslararası Bina Yönetmeliği, IV-A/B/C tipi yüksek kütle ahşapları tanıdı ve sırasıyla 18, 12 ve 9 katlı ahşap binalara izin verdi. Bu, kentsel ölçekte daha düşük karbonlu yapılar için yasal bir yeşil ışık oldu.

Pandemi Sonrası Alan ve Uzaktan Çalışmanın Etkisi

COVID-19, iç mekan havasını tasarımın itici gücü olarak yeniden tanımladı. Rehberlik, bulaşıcı aerosolleri kontrol etmek için ASHRAE 241-2023 gibi yeni standartlara dönüştü ve “minimum kod” havalandırmanın ötesine geçerek, filtreleme, hava dağıtımı ve temiz hava dağıtım oranlarını birinci sınıf tasarım kriterleri olarak dikkate alan stratejilere doğru ilerledi. İşyerlerinde, birçok ülkede hibrit ve uzaktan çalışma modelleri devam etti, bu da günlük işgal oranını düşürdü ve sahipleri, metrekareyi gerçekte ne için kullandıklarını yeniden düşünürken, esnek zemin plakaları, daha iyi akustik ve gün ışığına zengin işbirliği alanları peşinde koşmaya itti.

Bu değişiklikler şehirlerde dalga dalga yayılıyor. Bazı ofis kuleleri inceleniyor veya konutlara dönüştürülüyor; birçok kampüs, şeffaf operasyonlarla kullanıcıları güvence altına almak için WELL Sağlık-Güvenlik ve benzer çerçeveleri takip ediyor. Buna paralel olarak, hareketlilik ve yakınlık planlaması — 15 dakikalık mahalleler ve “evine yakın çalış” gibi kavramlar — iklim stratejileri olarak da işlev gören halk sağlığı araçları olarak ilgi gördü ve yaşam, çalışma ve hizmetleri daha kısa yolculuklar ve daha dayanıklı yerel yaşamla birleştirdi.

Tasarımda Kamusal Alanın ve Sosyal Eşitliğin Geri Kazanılması

Pandemi sırasında sokaklar güvenlik valfi görevi de gördü. Şehirler, adil dağıtım ve hızlı inşa taktikleri vurgulayan NACTO’nun “Pandemiye Müdahale ve İyileşme için Sokaklar” gibi kaynaklardan yararlanarak şeritleri yürüyüş, bisiklet ve yemek yeme amaçlı olarak yeniden düzenledi. New York’un Açık Sokaklar programı, bu fikirlerin çoğunu kodlayarak, seçilen koridorları yıl boyunca ortaklar, erişilebilirlik ve operasyonlar için kurallar içeren topluluk alanlarına dönüştürdü. Alınacak ders şudur: Politika ve tasarım birlikte hareket ettiğinde, küçük ölçekli, düşük maliyetli hamleler tüm mahalleleri yeniden programlayabilir.

Uzun vadede, şehirler sağlık, iklim ve adaleti aynı iğneye takıyor. Trafiği yeniden düzenleyerek sokakları insanlara geri kazandıran Barselona’nın süper blokları, gürültü ve kirliliğin azaltılması ve refahın artırılmasıyla olan bağlantıları açısından incelenmiştir; araştırmacılar kanıtları daha da netleştirirken, yönü de açıktır. Daha geniş kapsamlı Sürdürülebilir Kalkınma Hedefleri, güvenli, kapsayıcı yeşil alanlara evrensel erişimi talep ederek, mimarlara kamusal alanın bir lüks değil, günlük yaşamın altyapısı olduğunu hatırlatmaktadır.

Dök Mimarlık sitesinden daha fazla şey keşfedin

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.