A fascinating monument rising by the sea in the heart of Istanbul. Topkapi Palace, with its walls reeking of history, is a marvel that rises on Istanbul’s Sarayburnu and represents more than just a building. This stunningly beautiful palace is like a time machine that holds the brightest memories and secrets of the Ottoman Empire. Throughout its more than 600-year history, it served as the center of the state for 400 years, not only with stone walls, but also with the heart of the empire. A symbol of throne and splendor, this palace is the place where Ottoman sultans established their thrones, signed autographs and shaped world history. The greatness of Topkapi Palace is not only physical, but also the high meaning it has carried throughout history. Every wall, every corner is a witness to thousands of stories and experiences. While its unique architecture fascinates its visitors with the works of art hidden in every detail, it stands like a portal that carries the traces of the past to the present.

Let’s examine this unique historical building together…

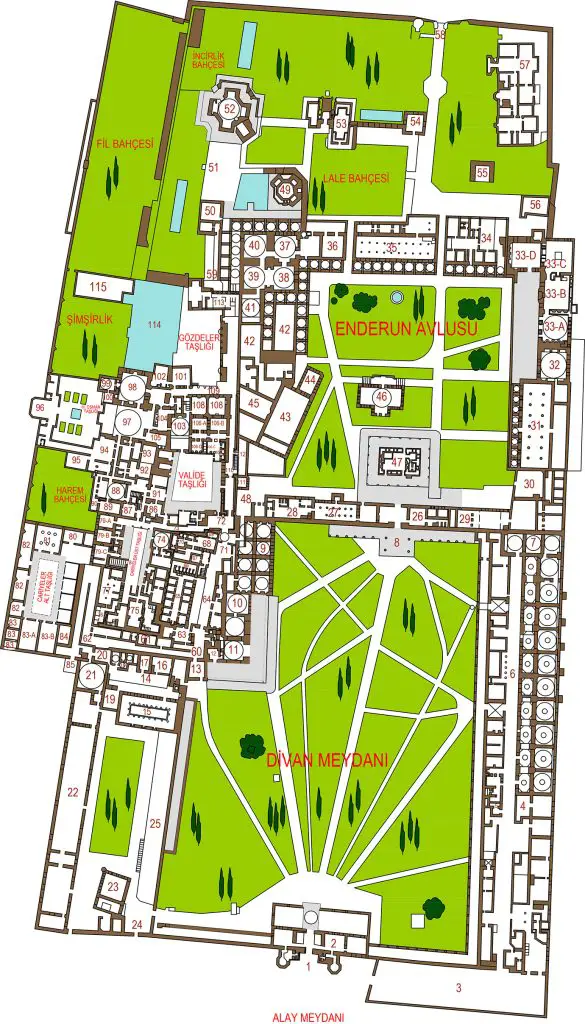

Topkapi Palace was built on the highest hill of Istanbul during the years it was built and had a magnificent view. The palace is also remarkable in terms of architecture. The unique structure bears the traces of many different periods. There are influences from the Islamic, Byzantine and Ottoman periods. The combination of these differences adds a distinct beauty to the palace.

Inside Topkapi Palace, there are the living quarters of the sultans, the harem, places where religious and official ceremonies are held, study rooms, courtyards and gardens. When you enter the palace, you will feel like you have embarked on a journey into its history and rich culture. Carrying the traces of thousands of years of history, Topkapi Palace offers a journey through time.

- A symbol of the Ottoman Empire, Topkapi Palace is one of the most historically and architecturally significant buildings in Istanbul.

- The architectural design of the palace has continued to evolve with buildings and additions from many periods, making it a unique and complex structure.

- The main palace building is surrounded by a complex of courtyards and buildings and consists of many rooms used for different purposes in different periods.

- The architecture includes traditional Ottoman design as well as influences from various periods, particularly Byzantine and Seljuk architecture.

- Pools, gardens and decorations in the inner courtyards add to the aesthetic richness and beauty of the palace.

- The harem section is the most mysterious and intriguing part of the palace and is considered the center of Ottoman court life.

- Given its architectural, religious, cultural and political significance, Topkapi Palace is a symbol reflecting the power and wealth of the Ottoman Empire.

- Restoration work is constantly underway to preserve the palace’s original splendor and offer visitors the best experience.

- Visitors have an in-depth experience through carefully organized museums to explore the history and architecture of the palace.

- As an important part of Istanbul’s cultural heritage, Topkapi Palace serves as an unforgettable destination and learning center for local and international visitors.

There are also museums in many parts of the palace that exhibit artworks and collections from the Ottoman Empire’s period. In the museums in the palace, there are many historical artifacts such as valuables, jewelry, paintings and manuscripts belonging to the priceless Ottoman sultans. Thanks to these museums, you can get to know the rich culture and art of the Ottoman Empire more closely.

Let’s examine this magnificent structure that witnessed the centuries of the Ottoman Empire.

Topkapi Palace History

Topkapı Palace was built by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror in 1478 and was the administrative center of the state and the official residence of the Ottoman sultans for about 380 years until Abdülmecitbuilt Dolmabahçe Palace. Topkapı Palace, which was not built with all its additional buildings at once like Dolmabahçe Palace, expanded with additional buildings until the 19th century.

Topkapı Palace was evacuated after the construction of Dolmabahçe Palace when the dynasty started to live there. After being abandoned by the sultans, Topkapı Palace, where many officials lived, never lost its importance. The palace was restored from time to time. The Department of Holy Relics, which was visited by the sultan and his family during Ramadan, was given special importance to be maintained every year.

The first time Topkapı Palace was opened to visitors as a museum was during the reign of Abdülmecit. The British ambassador of that period was shown the items in the Topkapı Palace Treasury. After this, it became a tradition to show the antiquities in the Topkapı Palace Treasury to foreigners, and during the reign of Abdülaziz, glass showcases were built in the empire style, and the antiquities in the treasury began to be shown to foreigners in these showcases.During the reign of Abdülhamid II, Topkapı Palace Treasury-i Hümâyûn was planned to be opened to the public on Sundays and Tuesdays, but this could not be realized due to the abdication of Abdülhamid II.

With the order of Mustafa KemalAtatürk, on April 3, 1924, Topkapı Palace was connected to the Istanbul Directorate of Museums of Antiquities to be opened to the public on April 3, 1924, and started to serve under the name of Treasury Chamberlain and then Treasury Directorate. Today, it continues to serve under the name of Topkapı Palace Museum Directorate.

In 1924, Topkapı Palace was opened as a museum on October 9, 1924, after some minor repairs were made and the necessary administrative measures were taken for visitors to visit. It is the first museum of the Republic. The sections opened to visitors at that time are Kubbealtı, Arz Room, Mecidiye Pavilion, Hekimbaşı Room, Mustafa Pasha Pavilion and Baghdad Pavilion.

Topkapı Palace, which attracts large crowds of tourists today, is one of the historical monuments located in the Historical Peninsula region of Istanbul and was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985. The palace was the residence of many sultans who ruled in Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire.

Topkapi Palace was started to be built in the 15th century by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror and expanded during the reigns of subsequent sultans to its present magnificent form. The palace is of great historical and cultural importance, both for its palace structure and its museum.

Today, the palace complex covers an area of approximately 300,000 square meters and is one of the largest palace-museums in the world with its various buildings, impressive architecture, magnificent collections and approximately 300,000 archival documents.

When you take a stroll inside Topkapi Palace, you can visit important sections such as the Sultan’s Chamber, the Harem Chamber, the Enderun School and the Topkapi Palace Museum. In these areas, it is possible to see many historical artifacts and works of art related to Ottoman palace life.

The garden of Topkapi Palace is also very impressive. It offers a visual feast to its visitors with its large and beautiful gardens, fountains and views. While strolling through the gardens, you can enjoy the historical atmosphere and tranquility.

Sections inside Topkapi Palace

Located right next to Hagia Sophia, Topkapi Palace is one of the most important winter palaces of the Ottoman Empire and has witnessed many important events throughout history. This magnificent structure is one of the most magnificent monuments in Istanbul and offers its visitors a unique historical and cultural experience.

The sultanate gate on the Hagia Sophia side, symbolizing the entrance to the palace, invites visitors into the depths of history. As soon as you step through this gate, you feel like you are on a journey through time. As you move forward, you are greeted by four fascinating courtyards. Each courtyard is surrounded by different architectural structures and has details that reflect the aesthetic values of the period.

Historical Significance

Topkapi Palace is a symbolic and historical landmark of Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. The palace was used as the residence of the Ottoman sultans and was also a center where administrative and political affairs were conducted. In addition, important state ceremonies and events were held in the palace.

The architectural features of Topkapi Palace are an important monument reflecting the rich cultural heritage of the Ottoman Empire. Both the structures and decorations inside and the gardens show visitors the splendor and beauty of the Ottoman period. For this reason, Topkapi Palace has been a great center of attraction, both architecturally and historically.

- Bâbüsselâm

- Doorkeeper’s Apartment

- Cabinet Stove

- Cooks Masjid

- Cooks Bath

- Kitchens

- Helvahane

- Bâbüssaâde

- External Treasury

- Grand Vizier Room

- Divan-ı Hümâyûn

- Tower of Justice

- Cabinet Dome

- Zülüflü Axemen’s Quarry

- Zülüflü Baltacılar Ward

- Zülüflü Baltacılar Masjid

- Zülüflü Baltacılar Külhanı

- Zülüflü Baltacılar Hamam

- Zülüflü Baltacılar Rest Hall

- Shawl Circle

- Raht Treasure

- Has Stables

- Beşir Aga Masjid

- Funeral Door

- Mehterhane

- Bâbussaade Agha Office

- Enderun School Great Room

- Enderun School Bath and Footpaths

- Enderun School Small Room

- Hünkâr Hamam Külhane

- Seferli Ward

- Fatih Mansion Bath

- Fatih Mansion 33-a) Fatih Mansion Rest Room 33-b) Sultan’s Room 33-c) Eyvan 33-d) Fatih Mansion Treasury

- Cellar Ward

- Treasurer Ward

- Squire Ward

- Arzhane

- Sofa with Fountain

- Has Oda Masjid

- Has Room (Hırka-i Saadet Apartment)

- Destimâl Room

- Has Room Ward

- Agalar Masjid

- Hünkâr Mahfili (Sultan Namazgah)

- Harem Ladies Masjid

- Enderun Library (Third Ahmed Library)

- Supply Room

- Kuşhane Gate (Gate Opening to Harem)

- Revan Pavilion

- Circumcision Room

- Iftariye Kameriyesi

- Baghdad Pavilion

- Sofa Pavilion

- Hekimbasi Room

- Esvab Room

- Sofa Masjid

- Mecidiye Mansion

- Gulhane Gate

- Iron Gate (Gate to Harem)

- Sofa with Fountain

- Karaağalar Hamam and Külhane

- Big Ride

- Karaagalar Masjid

- Elmagalar gizzard

- Elm Ward

- Elmagalar Footpath

- Şehzade School

- Dârüssaâde Agha Sofas

- Dârüssaâde Agha Chamber

- Dârüssaâde Agha Hamamı

- Curtain Door

- Duty Station

- Concubine Corridor

- Cariyeler Hamam

- Concubines Kitchen and Pantry

- Concubines Footpath

- Concubine Ward

- Stairs to the Concubines’ Subcourt

- 79-a) First Women’s Suite 79-b) Second Women’s Suite 79-c) Third Women’s Suite

- Department of Nurses

- Concubine Ward

- Woodshed

- Cariyeler Hospital Bath 83-a) Gasilhane 83-b) Laundry

- Footpaths

- Shawl Gate

- Valide Sultan Kitchen

- Treasurer’s Apartment

- Valide Sultan Sofas

- Valide Sultan Bedroom

- Valide Sultan Place of Worship

- Valide Sultan Apartment Main Entrance

- Valide Sultan Hamam

- Hünkâr Hamam

- Sultan Abdulhamid I Office

- Sultan Selim III Apartment

- Sultan Osman III Apartment

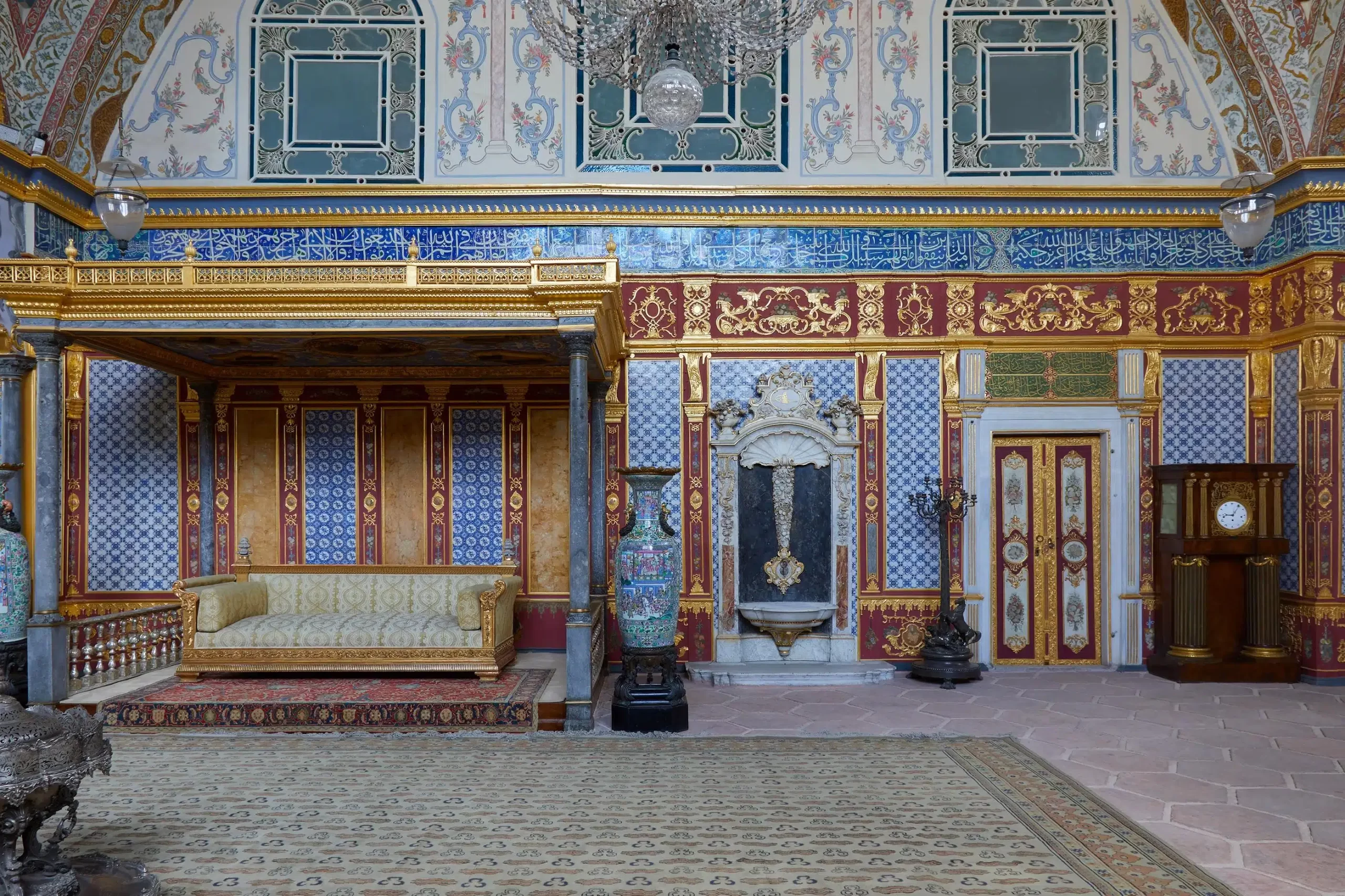

- Hünkâr Sofas

- Murad III Mansion

- Sultan Ahmed I Pavilion

- Sultan Ahmed III Pavilion

- Sultan Osman II Pavilion

- Sultan Mehmed IV Pavilion

- Sofa with Hearth

- Fountain Sofa

- Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Apartment

- 106-a) First Haseki Sultan Apartment 106-b) Second Haseki Sultan Apartment 106-c) Third Haseki Sultan Apartment 106-d) Fourth Haseki Sultan Apartment

- Warehouse

- Harem Treasure

- The Jinns’ Place of Consultation

- Golden Road

- Aviary Department

- Kushane Cuisine

- Mabeyn-i Hümâyûn Department

- Big Pool

- Aslanhane

In the first courtyard, a large square decorated with gardens and flowers welcomes you. In this square, there are areas where Ottoman sultans held ceremonies. The second courtyard has a quieter and more peaceful atmosphere. Here is the harem section of the palace and many fountains and pools. As you stroll through this courtyard, you are enveloped by history and beauty intertwined.

The third courtyard is one of the most lively and vibrant parts of Topkapi Palace. This is where the main buildings of the palace are located and where government business is conducted. As you explore the unforgettable views of the palace, you feel the splendor of the Ottoman Empire. The final courtyard is protected by the walls surrounding the palace and offers spectacular views of the Bosphorus.

Topkapi Palace is not only a palace, but also the center of the Ottoman Empire and a cultural heritage. With thousands of years of history, it bears the traces of many different civilizations. Visitors can not only explore historical buildings and works of art, but also experience the lifestyle and culture of the Ottoman Empire.

Topkapi Palace is one of the most important tourist attractions in Istanbul, offering visitors an unforgettable experience. You will take a journey through history, discover the splendor of the Ottoman Empire and enjoy a unique cultural atmosphere. Visiting Topkapi Palace is a must-do activity for anyone who wants to discover the historical and cultural richness of Istanbul.

I. Courtyard

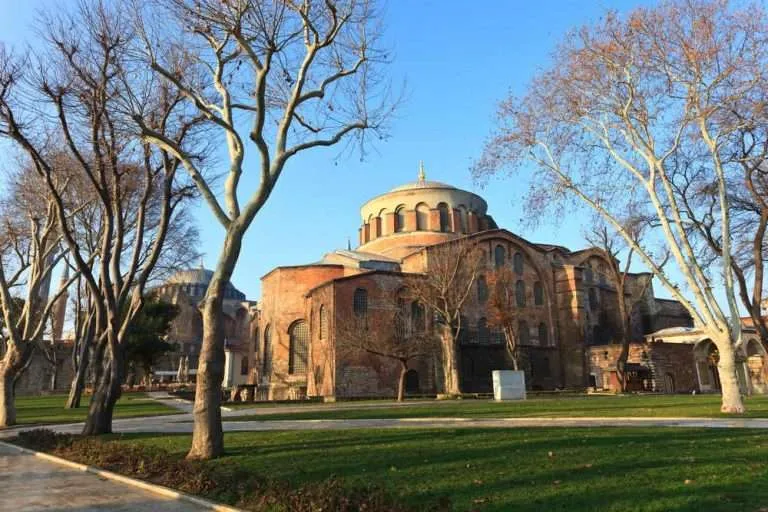

The buildings in the first courtyard (Alay Square), which was the first courtyard of Topkapı Palace and accessible to the public, housed various services of the palace. Among these buildings were the Hagia Irene Church, which was used as a Gibehane, the Mint, the Bakery, the Hospital, the Wood Warehouse and the Strawmakers’ Quarry.

Hagia Irene Church was built as a religious building during the Byzantine Empire and had a special position as it was located inside the palace. The building was used for various purposes over time and functioned as the public face of the palace. Today, it is known for hosting cultural events.

The Mint was an important building where the minting of coins in the palace was carried out. Used during the Ottoman Empire, this mint served as a workshop where precious metals were melted and processed.

The bakery was a structure used to produce bread and bakery products needed by the palace. Here, carefully selected grains were skillfully processed to produce the delicious breads and cakes that graced the palace’s rich tables.

The hospital was a building used to provide health care to the palace residents and visitors. Here, physicians and health workers worked to treat various diseases and alleviate health problems.

The Wood Warehouse was a storage area used to meet the heating and energy needs of the palace. Considering that the palace was a large structure, it is understood that the need for wood was quite high. Thanks to this storehouse, the inhabitants of the palace could always live in a warm and comfortable environment.

The Strawmakers’ Quarry was used as an accommodation and resting area for the crowded staff of the palace. In addition to this hearth, where the art of wicker-working was practiced, there were also shops to meet the basic needs of the staff.

In this way, the first courtyard of the palace contained different but important buildings. In addition to contributing to the functioning of the palace, these buildings also provided services to the public, making the palace visually and functionally rich.

II. Courtyard

The second courtyard of the palace is the Divan Square (Justice Square), where state administration took place. Many important ceremonies have taken place in this fascinating space throughout history. In the center of Divan Square is the Divan-ı Hümayun (Kubbealtı), the place where divan meetings were held in the Ottoman Empire. This was a center where the highest level decisions of the state were taken, the palace bureaucracy gathered and justice was administered.

An important building accompanying the Divan-ı Hümayun is the Divan-ı Hümayun Treasury. This building, where the state treasury was kept in the Ottoman Empire, attracts attention with its magnificent architecture. In addition to these important buildings of the Justice Square, there is also the Justice Tower, which symbolizes the justice of the sultan. The Tower of Justice was built to represent the justice and fairness of the ruling class of the palace.

Other buildings next to the Kubbealtı include the entrance to the Harem Chamber and the Zülüflü Baltacılar Ward. The Harem Apartment is the area where the sultan’s family lived and is one of the most secret and private parts of the palace. The Zülüflü Baltacılar Ward is a building where the palace guards stay. In this fragrant garden, there are guards who play an important role in the security of the sultan and the protection of the palace.

To the north of the Justice Square is the Babüssaade, where important ceremonies such as the julus, eve, feast and funeral are held. This is the place with historical significance, where the standards were handed over to the sovereigns. Babüssaade is the point where the palace opens to the public and where the monarch interacts directly with the public.

Behind the porticoes of the Justice Square are the palace kitchens and ancillary service buildings. These buildings are part of an enormous organization, responsible for feeding the thousands of inhabitants and visitors to the palace. The cooks, maids and other staff who work here support the bustling life that goes on in the palace.

Courtyard III

The Third Courtyard, the Enderun (inner palace), houses the wards and buildings belonging to the Palace School established during the reign of Sultan Murad II, as well as the spaces belonging to the Sultan.

While the Arz Room where the Sultan received statesmen and some foreign ambassadors, the Fatih Pavilion / Enderun Treasury and the Has Room are the places belonging to the Sultan, the wards belonging to the Enderun Palace School, known as the Small Room, the Great Room, the Seferli, the Cellar, the Treasury and the Has Room, are lined up around the courtyard from the Babüssaade entrance.

The 15th century Agalar Mosque, placed diagonally across the courtyard, and the Ahmed III Library, which was built after the demolition of the pavilion with pool during the reign of Ahmed III, emphasize the importance given to Enderun education.

Courtyard IV

After the Enderun Courtyard, one passes to Courtyard IV, where the pavilions and hanging gardens belonging to the Sultan are located. In this space, which can also be accessed through the doors of the Has Room opening to the Marble Sofa, there are the Circumcision Room, Baghdad and Revan Pavilions and the Iftariye Kameriyesi, which are the most distinguished examples of the classical pavilion architecture of Ottoman art. On the lower level of Courtyard IV, there is a hanging flower garden, the wooden Kara Mustafa Pasha Pavilion, the Hekim Başı Tower, and on the lowest level, the Sofa Mosque, the Mecidiye Pavilion and the Esvab Room, which were built during the reign of Sultan Abdülmecid and were the last buildings of the Palace.

It is known that there are many pavilions and pavilions that have not survived to the present day, except for the substructure of the Tiled Pavilion, Sepetçiler Pavilion and İncili Pavilion among the pavilions within the Hasbahçeler surrounding Topkapı Palace.

I. Courtyard and its architectural parts

Courtyard I, where the outer service buildings called Birûn are located, is the largest courtyard of the Palace. The Ottoman sultans used to pass through this courtyard in splendor on their way to and from campaigns and during processions (ceremonies) such as the Friday Salute. This courtyard was used as a waiting area for janissaries, servants and their horses before various ceremonies and during the reception of ambassadors. Unlike other parts of the palace, the public was allowed to enter this courtyard.

On both sides of the courtyard there were external service buildings. On the left were the wood storerooms, the workshops where the mats for the carpets were made, and the construction and repair workshops. Among the buildings on this side, the church of Hagia Irene, which was used as an armory, and the Mint, which was built in the 16th century and renovated and expanded in the 18th century, still exist today. In the Mint, where gold and silver coins were minted, there were workshops belonging to the Ehl-i Hiref organization, the artists and artisans of the Palace. To the right of the courtyard were the Enderun Hospital where the Enderunlu inner boys were treated, the Dolap Furnace, which formed the water distribution system of the Palace, and the Has Bakery, which produced bread (fodla) and bagels for the Palace. All these buildings were separated from the courtyard by high walls. Near the second gate of the palace, there was a small pavilion called the Deavi Pavilion, where the people submitted their petitions and complaints.

Hagia Irene

Built in the 4th century, Hagia Irene Church was rebuilt by the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian in 548 after a fire in 532. The basilical-planned building with three naves consists of three parts: the main space (naos), narthex (entrance) and atrium (courtyard). On the half dome of the apse, there is a wide-armed cross on a gilded mosaic background, and on the apse arch there is an inscription taken from the Torah that means “God is the name of the one who makes you ascend to heaven with his good deeds on earth”.

Since it was not converted into a mosque after the conquest of Istanbul, not much change was made inside and outside the space, and it was named “Cebehane” because it was used as a place where weapons and booty were stored.

There are two repair inscriptions on the entrance portico built during the reign of Ahmed III. This inscription dated 1726 indicates that the building was repaired as Darü’l-Esliha and the weapons stored here were organized and turned into a weapons museum. The second inscription on the portico is dated 1744 and it is understood from this inscription that the building was turned into Cebehane again after the repairs made during the reign of Mahmud I. In the 19th century, the building, which continued to function as a warehouse under the name “Harbiye Ambarı”, was transformed into a museum in two sections under the name Mecma-i Esliha-i Atika and Mecma-i Âsâr-ı Atika (Museum of Old Weapons and Antiquities) on the initiative of Tophane Müşiri Fethi Ahmed Pasha in 1846. The building, which later became a warehouse again, was used as a Military Museum between 1908 and 1940.

Babüsselam

It was built by Fatih Sultan Mehmed in 1468. After the repairs made during the reign of Kanuni, the gate reflects the classical elements of 16th century Ottoman architecture with its cut stone, wide arched portal vault and side niches, and is similar to the contemporary European castle gates with its two towers. The iron gate was built in 1524 by Isa bin Mehmed. The facade facing the first courtyard has the Kelime-i Tevhid, Sultan Mahmud II’s tughra, repair inscriptions dated 1758 and Sultan Mustafa III’s tughra on the sides. The facade facing the second courtyard has wide porticoes decorated in rococo style in the 18th century. The landscape-themed wall paintings here are dated to the 19th century. On both sides of the gate, the wards used by the gate guards called “Bevvabân-ı Dergâh-ı Âli” have not survived to the present day.

This monumental gate, which no one but the Sultan could enter on horseback, gave access to the main parts of the Palace. Even today, visits to the Museum start from this gate.

Bâb-ı Hümâyûn

Bâb-ı Hümâyûn, one of the three ceremonial gates of Topkapı Palace and the gateway to the First Courtyard, was built by Mehmed the Conqueror in 1478. Originally a two-storeyed, symmetrical, rectangular gate with a domed space between the interior and exterior, it is reminiscent of medieval castles and the monumental portals of Seljuk buildings with niches on either side. There are janitor wards on both sides. The upper floor was used as a Hünkâr Pavilion where the sultans watched various processions (ceremonies). On the inner and outer facades of the door are verses from the Holy Qur’an, Sultan Abdülaziz’s tughra and an Arabic inscription bearing the signature of Ali bin Yahya es-Sufi and giving the date 1478.

When we translate this inscription into today’s language, the following sentences are written: “By the grace and permission of Allah, the Sultan of the two continents and the Sultan of the two seas, the shadow of Allah in this world and the hereafter, the favorite of Allah in the East and the West, the ruler of the lands and the seas, the conqueror of the Castle of Constantinople, Sultan Mehmed Khan son of Sultan Murad Khan son of Sultan Mehmed Khan, may Allah make your property eternal and raise your position above the brightest stars of the sky, by the order of Abu’l-Feth Sultan Mehmed Khan, in the blessed year of 883In the month of Ramadan, the foundation of this blessed fortress was laid and its structure was firmly consolidated to strengthen peace and tranquility”

II. Courtyard and Architectural Sections

This courtyard, which was the administrative center of the Ottoman Empire and a ceremonial area, was shaped during the construction of the Palace and was expanded and renovated in the 16th century, especially during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. The courtyard is surrounded by porticoes on all four sides. The most important axis of the courtyard, which has various axes, is the Babüssaade axis representing the Sultan. To the right of the courtyard are the Palace kitchens, to the left are the Divanhane (Divan-ı Hümâyûn or Kubbealtı), the Outer Treasury, the Harem’s Carriage Gate, the Tower of Justice, the Zülüflü Baltacılar Ward, while on the lower level behind the porticoes on the left side at the entrance to the courtyard are the Stables and the Beşir Ağa Mosque. This courtyard, where the Divanhane, where state affairs were discussed four times a week, and the Tower of Justice towering above it, was also called Divan Square or Justice Square.

The Sultan’s enthronement ceremony called Cülus, the ceremony of handing over the flag to the Grand Vizier before the army set out on a campaign, the arefe divan, the feasting ceremony, the funeral ceremony of the sultans, the ulûfe ceremonies organized during the payment of quarterly salaries to the sipahi and janissaries, and the reception of ambassadors were held in this courtyard. In this ceremony, called the Galebe Divan, salaries and food were distributed to the janissaries and sipahi lined up on the porticoes of the courtyard for the ambassadors to see. In these ceremonies, which were held with great splendor, the wealth and power of the state was intended to be shown to foreign ambassadors.

Kubbealtı (Divan-ı Hümayun)

The first divanhane was a wooden structure built during the reign of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror (1451-1481). The present porticoed structure was rebuilt by Architect Alaeddin in 1527-29 during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, and then underwent various repairs and changes in various periods. In the 16th century, the interior walls were covered with marble. Some of the decorations in the Kubbealtı, the columns and arches of the portico with muqarnas capitals and the marble blank door with a crown symbolizing power belong to the 16th century period. In 1792, during the Sultan Selim III period, the building took its present appearance with ornaments and additions. Arch spaces were covered with gilded networks and doors with rococo reliefs were added. In 1819, during the reign of Sultan Mahmud II, the building underwent another repair; one of the two verse inscriptions on the façade belongs to Sultan Selim III and the other to Sultan Mahmud II. The arch wall of the Divan-ı Hümayûn pen has the tughra of Sultan Mustafa III.

Kubbealtı, where state affairs are discussed, consists of three sections: the Divan-ı Hümayûn pens where the decisions taken here are written, the notebooks where the decisions are written and the Defterhane where the documents are archived. The members of the Divan-ı Hümâyun would meet four days a week. The members of the Divan, namely the Grand Vizier, the viziers of the dome, the Anatolian and Rumeli kazasker, would discuss state affairs, make decisions to be submitted to the Sultan and hear cases. In case of need, the Sheikhulislam was also invited to the meetings. The other officials of the Divan-ı Hümayun were the engagement officer, notary, reis-ül küttab, tezkereciler and clerks. In these meetings, political, administrative, financial and customary affairs of the state and important cases of the people were discussed. In addition, the grand vizier’s receptions of ambassadors and the marriages of the sultan’s daughters were also held here.

The Ottoman sultans did not attend the meetings held in Kubbealtı. Most of the time, they would watch the meetings from behind the latticed window of a room in the Tower of Justice that overlooked the Kubbealtı, and when a wrong decision was taken, they would close the window curtain and end the meeting. The grand vizier and the viziers would then go to the Chamber of Arz and appear before the sultan to discuss the matter.

Kubbealtı has many symbolic elements that symbolize the justice of the state. The fact that the space was open and visible with gilded grids meant that there was no secrecy about the decisions taken here. The latticed window through which the sultan watched the meetings symbolizes that although the sultan delegated his authority to the statesmen, he personally ensured that no injustice was done to his subjects.

Pavilion of Justice

Built as a tower-pavilion during the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror (1441-46/1451-81), it was renovated during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. On top of the structure was a wooden pavilion with a conical cone. It was raised in 1820 during the reign of Sultan Mahmud II and an empire style pavilion was built on it during the reign of Sultan Abdülaziz (1861-76). The stairs of the five-story tower belong to the 19th century. As an example of traditional palace towers, the tower was built for the sultan to watch the city, the palace and especially the Divan meetings with its latticed room.

External Treasury

The Outer Treasury building, which is now used as the Weapons Section and was first built during the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror (1451-81), was demolished together with the old Divanhane during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent and rebuilt between 1526 and 1528. The space is covered with eight domes rising on three large pillars.

The Outer Treasury building was used as the official treasury of the state until the mid-19th century. Taxes collected from countries and provinces, revenues from spoils, as well as the hil’ats worn by ambassadors, silk and gold brocade caftans, sable and lynx furs, and the old record books of the Divanhane were kept here; the quarterly salaries (ulûfe) of janissaries and sipahis, navy and expedition expenses, and the salaries of public officials in the center were paid from here. The External Treasury, which was under the responsibility of the Defterdar, was opened and closed by being sealed with the seal of the sultan on the grand vizier.

Zülüflü Baltacılar Ocağı

The Zülüflü Baltacılar Quarry was established in the 15th century to pave the way for the army. Zülüflü Baltacılar were responsible for cleaning the harem and selamlık sections of the palace, safe and fast communication of the sultan, carrying and setting up the throne during the coronation and feast ceremonies, transporting belongings, and carrying the funerals of the sultan and his family members. The term “Zülüflü” (Zülüflü), given to the members of the hearth, comes from the hair braid-like zülüf (zülüf) hanging from the two sides of the pointed serape they wore on their heads. The wide upturned collars of their clothes and the zülüfüf hanging from both sides prevented them from seeing the surroundings during services within the Harem. The Zülüflü Baltacı Kethüdası was the most authorized supervisor of this chamber. Depending on the work they performed, the members of this room were named as chief axe-masters, divanhaneci, kilerci head axe-masters, company chief, odabaşı, yemişçi, suyolucu, koşucu.

Has Stables

The structure used for the horses of the sultan and Enderun aghas dates back to the first period of the palace. This stable, which housed a small number of selected horses of the sultans, was under the responsibility of an administrator called Imrahor. The single domed space at the northern end of the long rectangular stable structure and the rooms connected to it were used as the Raht-ı Hümâyun Treasury, where valuable horse harnesses were kept. The decorated ceiling of the domed space was brought from Köçeoğlu Mansion during the 1940 repairs. In this section, there are also the apartments of the Stable Commander (Chief Imrahor) and other administrators. It is understood from the inscription on the door of the Has Stable that it was completely repaired in 1736 and the old mosque and baths in the courtyard were rebuilt by Dârü’s-saâde Agha Beşir Ağa. The troughs in the courtyard belong to the reigns of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror (1451-81) and Sultan Murad III (1574-95). The passage called the Stable Gate or Meyyit Gate connects the Has Stable Courtyard to the Regimental Square.

Beşir Ağa Mosque and Bath

It was built in 1736 by Hacı Beşir Ağa, the Dârüssaâde Agha of Sultan Mahmud I, for the use of the Has Stable officials. This historical building is an example of the fevkani (raised from the ground) mosque in the late classical style. Its walls are covered with plaster in imitation of stone-brick masonry in the 18th century fashion. The mosque has a single minaret, which adds an aesthetic element to the building and is used to announce the call to Islam.

This mosque, whose wooden parts and cloister have now been renovated, is characterized by its early baroque stained glass windows and marble mihrab. The stained glass windows, which retain their original features, are decorated with religious symbols while displaying a magnificent play of light inside the mosque. The marble mihrab is the part of the mosque that shows the direction of qibla and is the focal point of worship.

The hamam, located to the south of the mosque, is a two-domed structure. This bath was built in an integrated manner with the mosque and is a part of the historical heritage. The hamam was used as a part of the social life of the period and thus met the needs of people for washing and cleaning. Today, it is restored and has become a place visited by tourists.

Palace Kitchens

The palace kitchens serving the Sultan, the Enderun and the Harem people opened to the Second Courtyard with the Kiler-i Amire, Has Kitchen and Helvahane doors behind the porticoes. The sherbet house/jam house, halvahane, kitchens, cooks’ masjid, oil house and cellar, now used as the palace archive, are located on three sides of a long inner courtyard, with the cooks’ ward opposite. The kitchens served various groups of the palace hierarchy and the state officials serving in the Kubbealtı during the Divan meetings.

The kitchens, divided into ten sections, were built in the 15th century and expanded in the 16th century during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. After the 1574 fire, they were repaired by Mimar Sinan. The flat domed buildings to the south of the kitchens date from the 15th century. The walls are masonry and the covering system is brick.

The halvahane part of the kitchens belongs to the Kanuni period and has four rooms. There is a foundation inscription dated 1767 and a fountain to the right of the entrance. This fountain and the Kelime-i Tevhid inscription on the door must belong to the repairs after 1574. From the halvahan, one passes to the jam house/sherbet house section on the short side of the courtyard. The inscription on this door with the name of Hacı Mehmed Ağa and the date 1699 is related to the repair of the building. The kundekâri doors with geometric interlacing motifs and the Iznik tiles with ulama belong to the same period. Built in the 18th century, the Cooks’ Masjid has a wooden mahfile. The wooden porticoed service road and wooden ward structures of the kitchens were removed in the 1920 repairs.

Babüssaade

This gate connects the Divan Square to the Enderun Courtyard, where the sultans’ courtly life at the palace took place and where the inner palace organization and the palace school were located. In front of this gate, which represented the Sultan, ceremonial or emergency meetings called jülus, feasts, eve divan and foot divan were held. Except for such events, the sultan would not leave the Divan Square through this door. Symbolically the sentence door of the sultan’s house and always kept closed, passing behind this door without permission was considered the biggest violation of law against the absolute administration. This gate, which was under the responsibility and control of Bâbüssaâde Agha, the most authorized agha of the palace, was built with a dome and portico in the 15th century during the construction of the palace. The Rococo covering system and ornaments belong to the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid I (1774-1789) and Sultan Selim III (1789-1807). The wooden-ceilinged dome is supported on four marble columns with ion capitals, one of the classical types of the Turkish baroque style during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid I. The landscape frescoed architrave, the simple decorations of the ceiling and eaves, and the carnations on the dome and pulley reflect the empire style of Sultan Mahmud II (1808-39). The keystone on the front facade bears Sultan Mahmud II’s own monogram and besmele inscription, the sides are decorated with verse odes praising Sultan Abdülhamid I, and the back facade bears inscriptions bearing the names of the same sultans. These inscriptions document the repairs the gate underwent.

On either side of the gate are the Bâbüssaâde Agha Department and the wards of the Akağalars in charge of the Enderun. It opens to the façade of the divan square with a portico with a muqarnas cap and pointed arches dating back to the 16th century.

Sukhum Fort inscription

This inscription is one of the artifacts of the historic Sukhum Fortress of the Ottoman Empire. Sukhum Fortress was built during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III, i.e. between 1703-1730. Located on the Black Sea coast, this fortress was used for both military and civilian purposes due to its strategic location.

However, the Sukhum Fortress and its inscription are important not only for their architectural and historical value, but also for the events that took place during the Ottoman-Russian War. This war took place between 1877-1878 and was fought between the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire. The Sukhum Fortress was brought to the Palace as a result of this conflict.

An important detail of the inscription is the inclusion of Sultan Abdülhamid II’s 1877 tughra at the beginning. This tughra is an important symbol of Abdulhamid II’s reign and was frequently used in various works of the Ottoman Empire.

The manzum inscription is a work of historical, cultural and artistic interweaving. It provides important information about the history of the Sukhum Fortress and the period of the Ottoman Empire.

Courtyard III (Enderun Courtyard) and its architectural sections

The Enderun, the selamlık section of the inner workings of the palace created for the sultan, was also called “Harem-i Hümayun” together with the Harem where the sultan lived with his family. The Enderun Courtyard, which was shaped during the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror (1451-1481), consists of the courtyard containing the buildings belonging to the sultan and the marble terrace and flower garden called Sofa-i Hümayûn, where the pavilions belonging to the sultan are located. In the Enderun Courtyard, there are also the wards of the Enderun School where the inner boys who were recruited to the palace through recruitment were educated.

The Enderun Organization, which was established by taking the organization of the Great Seljuk and Anatolian Seljuk States as an example, served for centuries as a school that trained high-level bureaucrats, soldiers and artisans for the state. The Ottoman sultans raised a loyal class educated with the principles of Islam and Turkish culture in accordance with the devshirme procedure, which continued from the first half of the 15th century until the end of the 17th century. After training some of the recruited inner boys in the palace and some in the army, they assigned them to positions in the upper echelons of the state. From the 18th century onwards, Turks started to be appointed to these positions.

The boys who were recruited through the devshirme method were first given to Turkish families to learn customs, traditions and language, and then sent to preparatory schools. Those who were successful were admitted to the Enderun School. Here, starting with the Great and Small Room wards, they would be educated in the Seferli, Kilerli, Treasury and Has Room wards in order, and would provide symbolic service in accordance with the functions of the wards, rising to the position of grand vizier, the second in command of the Empire.

As in the other spaces of the palace, the buildings belonging to the sultan were emphasized in the shaping of the Enderun Courtyard. The spaces used by the sultan, such as the Fatih Pavilion, the Has Room, and the Pool Pavilion, were gathered in the center and corners of the courtyard, while the wards of the Enderun inner boys, who were undergoing training, were placed at the edges. With their original appearance, the wards, which opened to the courtyard with porticoes and had wards, glasshouses and baths around a small hall inside, had an order according to the level of education. On either side of the Babüssaade, the Büyük and Küçük Oda wards for novice boys and the Seferli Ward, which was created in the 17th century by demolishing Selim II’s bathhouse, constituted the lower levels of the Enderun School. The others were the Kilerli, Treasury and Has Oda wards. It is known that the Has Oda ward was intertwined with the Has Oda. There is also the Agalar Mosque in this direction. In the middle of the Enderûn courtyard was the Pool Pavilion. In the 18th century, it was demolished and replaced by the Enderûn Library (Sultan Ahmed III Library).

After the abolition of the Janissary Corps in 1826, a new army was established and innovations were made in the education system. After this date, the Enderun School and its organization started to lose its importance.

Chamber of Arz

Located directly opposite the Bâbüssaade and integrated with this door with its eaves system, the Arz Room is the most important place in the Palace where the relations of the Sultans with the state administration are embodied. This room is also called the Arz Room or Arz Dîvanhane. It is the place called “makam-ı muallâ”, meaning the office of the sultan mentioned in the edicts. The sultans received the ambassadors of foreign states here and ceremoniously handed over the flag to the commanders going on an expedition. On Sundays and Tuesdays, called Arz Days, and after the Dîvan meetings, they held their private meetings with the state officials here.

The Arz Chamber, a classical example of the mansion style of Turkish architecture, is a vaulted structure consisting of a throne room and an ablution room next to it. It has two doors on the front facade and one door on the back facade. While the sultan used only the back door, the front door was used by the state officials and ambassadors who appeared before the sultan. The door on the left and the window with iron bars is where the gifts of the ambassadors were shown to the sultan. It is also called pişkeş gate (gift gate).

The most glorious period of the Chamber of Arz was during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. From the 16th century to the 19th century, the building underwent various repairs, and the poetic history inside the throne dome indicates that it was built during the reign of Sultan Mehmed III (1595-1603). The lacquered ceiling of the jewel-decorated throne depicts the struggle between a dragon and a simurg as a symbol of power among floral motifs. Although this throne room was saved from the fire in 1856 with little damage, the hearth mats, the tiles on the dome and wall surfaces, the wooden sashes of the doors and windows inlaid with baga and mother-of-pearl, and all the furniture inside were burned.

The Arz Room, which was renovated in the empire style by the architects and craftsmen of Dolmabahçe Palace after the fire of 1856 by Sultan Abdülmecid, has survived to the present day with its empire and neoclassical decoration. The marble relief inscriptions in the form of tughra on both sides of the door, praising Sultan Abdülmecid, were placed after this renovation. The 16th century tile panels were covered on the walls in the 19th century. The fountain to the right of the entrance was built by Suleiman the Magnificent. On the gate used by the sultans, there is the tughra and repair inscription of Sultan Mustafa III (1757-1774). There is an inscription written in the calligraphy of Sultan Mahmud II on the Pişkeş door.

Ahmed III Library (Enderun Library)

It was built by Sultan Ahmed III (1703-1730) on the site of the Pool Pavilion as a foundation library for the inner boys studying at the Enderun Palace School. Located in the center of the Enderun Courtyard, this building, the first library of the Palace, has an Arabic verse of six couplets on the sentence gate, which gives the date 1719 in ebced calculus. The inscription explains that Sultan Ahmed III had this building, in which books were to be collected, built with his own money to encourage the learning of science and to earn good deeds.

This building, also called the Enderun Library, consists of a domed central space rising above a vaulted substructure. This space is expanded with iwans on three sides. The exterior is covered with marble. There are two fountains at the entrance of the library, one on the building side and the other on the courtyard side. The palace is the most beautiful example of Tulip Period Mansion architecture that has survived without losing its features.

The interior of the Sultan Ahmed III Library is covered with 16th century Iznik tiles. The tiles were brought from other palaces and mansions of the sultans in Istanbul. The dome and vaults are decorated with floral motifs of the Tulip Period in malakâri technique. The window and door wings have classical geometric patterns inlaid with ivory. Window and door interiors are covered with 17th century ulama tiles, and the ceilings are inlaid with geometric stone like the Baghdad and Revan Mansions. There are built-in bookcases with silver wire cages between the windows. The collection, consisting of the books in Sultan Ahmed III’s own treasury and the books endowed by Sultan Abdülhamid I and Sultan Selim III, was preserved here until 1965, after which it was included in the Palace Library collection.

Fatih Pavilion (Enderun Treasury)

It is one of the first buildings built by Mehmed the Conqueror in 1462-63 to form the plan of Topkapı Palace. Like the other buildings belonging to the sultans in the palace, this one also has a quadrangular layout. The Fatih Pavilion reflects the lines typical of Imperial architecture with its large halls, iwan-like terrace, porticoed hall, high gate behind a pair of porphyry columns, deep windows and niches in the walls, and magnificent room hearth.

The Fatih Pavilion is a monumental application of the traditional outer house form in cut stone. The mansion’s two large cellars with massive walls and vaults have a substructure to cover a clover-planned baptistery from the Byzantine period. The building, which was covered with a wooden ceiling and lead roof when it was first built, was renovated in the 16th century and took its present appearance.

The Fatih Mansion, built by Fatih Sultan Mehmed as a viewing pavilion, soon became a place where treasure items were kept. After Yavuz Sultan Selim’s Egyptian expedition, the terraces and porticoes were covered with walls in order to preserve the treasury, which became quite rich. During the reign of Sultan Mahmud I (1730-1754), the green porphyry columns in front of the sentence gate were enclosed within the wall and a new space was created and named the Envoy Treasury. Thus, the monumental crown gate of the Fatih Pavilion and the entire façade facing Courtyard III were covered with windows and doors. In addition, a Jeweler’s Room was added here in 1766 for the on-site repair of Treasury artifacts. In the following periods, all these additions were removed and the building was restored to its 16th century condition.

Treasury Ward

The Treasury Ward, which was responsible for the palace treasury in the Enderun Courtyard, was of great importance during the Ottoman Empire. In this ward, the palace’s valuables, jewels, priceless works of art and other objects of treasure were stored and protected. An official called Hazinedarbaşı was in charge of the Treasury Ward. Hazinedarbaşı was both responsible for the execution of treasury-related affairs and also served as the supervisor of the Ehl-i Hiref organization, which produced the art and craft works of the palace.

Starting from the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror, the founder of the Ottoman Empire, the importance and presence of the Treasury Ward and Hazinedarbasi in the palace was constantly maintained. As a place where the wealth of the palace was kept, the Treasury Ward ensured the safety and protection of valuables. At the same time, precious stones, gold and silver objects reflecting the flamboyant lifestyle of the Ottoman Empire were stored and exhibited here.

However, the Treasury Ward was not only used for storage purposes. It was also a repository of valuable artifacts produced by artists, artisans and craftsmen in the palace. For this reason, the Treasury Ward housed unique handmade carpets, porcelains, ceramics, miniatures, jewelry and other similar works of art. These artifacts were part of the opulent and luxurious life of the palace and reflect the rich cultural heritage of the Ottoman Empire.

After the 1856 fire, the Treasury Ward building was renovated by order of Sultan Abdülmecid. While this fire destroyed many parts of the palace, it preserved the valuable contents of the Treasury Ward. The renovated Treasury Ward building still retained its importance and presence even in the last periods of the Ottoman Empire.

As such, the Treasury Ward was of historical significance, storing the riches of the Ottoman palace and reflecting the artistic and cultural heritage of the Ottoman Empire. This unique structure was a museum that could be visited for hours and shed light on the past of the Ottoman Empire, which was elegantly displayed to visitors.

Has Room and Department of Holy Relics

Built during the reign of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror (1451-1481) as the private apartments of the sultans in the Enderûn courtyard, the Has Oda (Hırka-i Saadet Dairesi) is a palace pavilion with two floors and a quadruple space layout. The double space at the entrance was named Şadırvanlı Sofa because of the marble fountain under the dome. The other two parts of the quadripartite space were designed as two domed rooms connected to each other and to the Sofa by doors.

The entrance of the Has Room Apartment has also survived to the present day with the changes made during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III (1703-1730). The Kelime-i Tevhid on the door, dated 1725 and written in celî sülüs calligraphy, is the work of Sultan Ahmed III, who was a good calligrapher. On both sides of the door, in the form of a tughra, are the phrases “Meliki Meliki Hakan-ı Emced” on the right and “Shari’a Saliki Sultan Ahmed” on the left.

The first room on the right at the entrance from the Sofa with Fountain is the Arzhane, where the sultan met with the Arz Aghas and where they presented their desires to the sultan. The second room in the corner is the Throne Room / Has Room, where the sultan’s throne is located and is the most important space of the building. Yavuz Sultan Selim I chose this room for the protection of the Holy Crown, which he brought with him after his Egyptian expedition, and made changes in the organization of the Has Room. Until the second half of the 16th century, the Sultans who stayed here until the end of the empire, sat on the throne here before the coronation ceremony, and visited the Holy House with official state ceremonies on the 14th and 15th days of Ramadan every year. The Has Room was meticulously restored by all sultans in honor of the Holy Crown, and almost every sultan endeavored to revitalize this place during his reign. The Has Room, as it has survived to the present day, has the most original tile design applied in the sultan’s quarters in the late 16th century in the palace.

The Has Room / The House of the Holy Cloth is now used as an exhibition hall for the Holy Relics kept in it for centuries.

When entering the Has Room from the Enderun Courtyard, a white marble bench stands out to the left of the door. This marble bench has a great symbolic meaning for the Ottoman sultans. The marble bench in question was reserved exclusively for the slain Ottoman sultans and their princes, and the coffin of the deceased sultan would be placed on the bench for the funeral prayers. Right next to the marble bench at the entrance of the Has Chamber, there is a well with a marble ring and an iron cover. This small well, the existence of which was hidden from the outside, is also related to the Chamber of the Holy Chamber. As the chamber was cleaned, the dust from the chamber was poured into this well as an expression of respect.

There is a marble mortar in the corner where the porticoes meet on the right of the entrance. In order to make the Has Room smell good, the Has Chamber people used to prepare courses here, which contained precious ingredients such as amber, sandalwood and oudwood. The courses, which were covered with gold leaf, were burned in the apartment to ensure that the place always smelled good.

In the 19th century, the Has Room ward and the porticoed section in front of the service buildings were closed and a new ward was built for the officials responsible for the Sacred Relics. The ward is used as an exhibition space for the Sultan Portraits collection.

Agalar Mosque

Ağalar Mosque was built during the reign of Fatih for the worship of the sultan, akağalar and inner boys. It is located on the Golden Horn side of the Enderûn Courtyard, after the Has Room. The large central space was covered with a wide barrel vault in the 18th century. There are two spaces on the narrow sides. The space on the Has room side has a separate mihrab. The space on the other side was reserved for the worship of the Seferli, Kilerli and Hazineli aghas. Three windows behind the large prayer room lead to the harem masjid. In addition to the sultans, Valide Sultan and Hasekis prayed here.

The walls are covered with 17th century tiles. The most interesting examples are the stacks with vav letters signed by Kemankeş Mustafa. This place was intended for high-ranking aghas to pray. According to the door inscription inside, Es-seyyid Mehmed Aga carried out the most important repair of the stone and brick structure in the previous centuries by renovating the adjacent masjid. The tile inscription on the inside of the door gives the date Hijrî 1136 (Miladî 1722) and the name “Es-seyyid Mehmed Aga”. After 1881, the building was used as a warehouse and was repaired in 1916. The other inscription dated 1928 and written by Kamil Akdik is dated 1928. The Agalar Mosque, which was repaired again in 1925, was named Yeni Kütüphane after the Ahmed III Library and other libraries in the Palace were gathered here.

Kilerli Ward

It was built by Mehmed the Conqueror within the design of Topkapı Palace, between the Fatih Pavilion and the Treasury Ward. The Kiler Kethüdası, the head of the Kiler Ward, was also responsible for the palace kitchens. The duties of the inner boys of the Kiler Ward included preparing the Sultan’s meals, setting and clearing the Sultan’s table, and preserving the valuable kitchen utensils that were served to the Sultan. In addition to preparing pastes, syrups, sherbets, nuts, etc. for the sultan, the inner boys would also prepare candles for the mansions, apartments and masjids of the palace. The inner boys of the Kiler Ward, who also prepared medicines for the patients staying in the Enderun hospital, would collect the “April rain” water, which was believed to be healing in April, and present it to the sultan.

When it was first built, the Cellar Ward was two-story and wooden. The floor was paved with patterned stone and there was a portico with marble columns in front of the ward. There was a furnace for the heating of the inhabitants of the ward. After the abolition of the Kiler Ward, it was demolished in 1847 and replaced by the Treasury Chamberlain’s Office. There is an arched passage between the Treasury and the Fourth Floor. The inscription on the arch of the passage is dated Hijrî 1152 (Miladî 1739).

In the repairs made between 1951-1967, the interior was converted into reinforced concrete and completely changed and opened to service as the administration building of the Topkapı Palace Museum Directorate. The building is still used as the Topkapı Palace Museum Directorate.

Kuşhane and Harem Gate

It is known that there was a small inner courtyard between the Agalar Mosque and the Small Chamber Ward until the end of the 19th century. From this courtyard, the Kuşhane door leads to the Harem. The existing Kuşhane next to the door, which is now used as the exit to the Harem Department, consists of two rooms on top of each other. The balcony in the upper room overlooking the courtyard was built in 1916. With its façade layout, it resembles a large-scale example of traditional birdhouses. However, the present condition of the building is not in accordance with its original appearance.

The inscription dated 1734/35 on the Kuşhane door of the harem states that Sultan Mahmud I (1730-1754) had the Kuşhane kitchen repaired.

Has Room Ward / Sultan Portraits

Hırka-i Saadet Dairesi is a historical building in Istanbul. In the second half of the 19th century, it was created by adding a vault to the porticoes of the Has Oda in the Enderun courtyard. This apartment is part of Topkapı Palace, the religious and political center of the Ottoman Empire.

The Chamber of the Holy House is a room where the clothes of the Prophet Muhammad, also known as the Holy House, which were held in high esteem by the Ottoman sultans, are kept. These clothes, which have a great sanctity in the Islamic world, have a religious and historical value.

The columns, domes and stone walls inside the building were built during the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror (1441-1446/1451-1481). This period coincides with the early years of the Ottoman Empire and is characterized by great architectural richness and aesthetics.

Courtyard IV

This part of the palace, called the Fourth Courtyard or Fourth Place, consists of the Tulip Garden and the terrace called Sofa-i Hümâyûn. In the first half of the 17th century, during the reigns of Sultan Murad IV (1623-1640) and Sultan Ibrahim (1640-1648), the terrace with a pool, also called the Marble Sofa, was expanded towards the Golden Horn and new pavilions were built. The marble Sofa porticoes took their present form in 1916.

The wooden Sofa Pavilion and the Stone Pavilion/Hekimbaşı Tower, which were used as private rooms by the sultans in the Lâla (Tulip) Garden below the terrace with pool, are the structures that have survived to the present day. In the garden, where various roses, tulips, hyacinths, carnations and jasmine flowers, as well as orange and lemon trees were grown, there were also vineyards and various fruit trees.

On the Marmara side of the Tulip Garden are the Mecidiye Pavilion, Esvap Room and Sofa Mosque, which were built in the empire style as the last buildings of the Palace in the 19th century. The garden is connected to the Has Garden, now Gülhane Park, by the Mabeyn Gate with a tower, reflecting the style of Sarkis Balyan, the architect of the Mecidiye Mansion.

Circumcision Room

The summer pavilion, located on the most spectacular facade of the palace facing Galata, is thought to have been built during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-1566). This pavilion is one of the most important architectural structures of the Ottoman period and has witnessed many historical events. This palace pavilion, designed as the sultan’s summer room, has a great historical and architectural value.

Also known as the Circumcision Room, this pavilion was used during the circumcision of the princes of Sultan Ahmed III (1703-1730). The circumcision ceremonies of the princes are considered as one of the important moments that shaped the future of the Ottoman Empire. For this reason, the Palace Pavilion, known as the Circumcision Room, has become an important historical and cultural symbol.

There is a small coffee stove at the back of the mansion, which has a square plan and a single room. This coffee stove is an element that reflects the social life of the period and adds a special charm to the mansion. Here, visitors of the Palace Pavilion can spend time drinking tea and coffee in a pleasant environment.

One of the most remarkable features of the Palace Pavilion is the blue-white tiles on its facade. These tiles are made in the saz style and belong to the famous 16th century painter Şah Kulu. The colorful and detailed tile work adds a fascinating look to the mansion. These tiles are considered an important example of Ottoman period art and are one of the elements that attract the attention of visitors.

The Palace Pavilion has undergone some renovations over time. In 1640, the space was renewed during the terrace arrangements made by Sultan Ibrahim. These terrace arrangements gave the mansion a wider and more spacious appearance.

Revan Pavilion

Built in 1635 to commemorate the conquest of Revan by Sultan Murad IV (1623-1640), the pavilion was constructed in the Sofa-i Hümayûn in the area gained by reducing the size of the pool that had existed since the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror (1451-1481). Thought to have been built by Koca Kasım Ağa, the chief architect of the period, the pavilion has an octagonal plan with three iwan. On the ceiling of the alcove between the two iwans on the eastern façade facing the Tulip Garden, there are some couplets from the Kaside-i Bürde.

In 1733, Sultan Mahmud I (1730-1754) created a foundation library in the wooden cabinets of the pavilion, which was extremely valuable for the Has Odalılar and was mainly composed of history books. This foundation library, which was developed by Sultan Osman III (1754-57) and Sultan Mustafa III (1757-1774), was included in the collection of the Palace Library after the Palace became a museum.

During the cleaning, called pars, of the Chamber of the Holy Crown, which was also attended by the Sultans, the Holy Relics were kept in the Revan Pavilion. In some sources, this pavilion is also referred to as the Sarık Room.

Baghdad Pavilion

Built to commemorate Sultan Murad IV’s (1623-1640) conquest of Baghdad, the pavilion was built at the end of the marble terrace, probably by the architect Koca Kasım in 1639, replacing a tower pavilion that had previously existed here. The verses on the sash surrounding the pavilion were written in white celî sülüs calligraphy on a blue background by Tophaneli Enderunî Mahmud Çelebi, one of the famous calligraphers of the palace. The Persian couplet on the door of the pavilion, which has no inscription, also includes the Word of God. In the cabinets of the pavilion with mother-of-pearl, baga and ivory carved wooden doors, books endowed by Sultan Abdülhamid I (1774-1789) and Sultan Selim III (1789-1807) were placed. The Baghdad Pavilion library was also included in the Palace Library collection after the Palace was turned into a museum. The small room behind the pavilion was used as a coffee stove.

Iftariye Kameriyesi (Moonlighting)

It was built during the reign of Sultan Ibrahim (1640-1648). The tombak pavilion, which is in the shape of a gazebo, was separated from the marble with its protruding position and was brought to a position overlooking the Golden Horn and Galata with the gardens below.

It is thought that the sultans used to break their fast here during Ramadan. For this reason, it must have been named İftariye. It is understood from the sources that during the feast ceremonies that coincided with the summer months, the sultans accepted the feast greetings of the Enderunlu here and watched the sports performances in the lower garden.

Sofa Pavilion

Known as Sofa Pavilion, Kara Mustafa Pasha Pavilion and Merdivenbaşı Pavilion, it was built during the reign of Sultan Mehmed IV (1648-1687). The pavilion, which consists of two independent sections called Divanhane and Şerbet Room, was repaired during the reigns of Sultan Ahmed III (1703-1730) and Sultan Mahmud I (1730-1754).

Sofa Pavilion is located in the garden of Beylerbeyi Palace in the Üsküdar district of Istanbul. This pavilion is an important part of the palace complex and has been used by various sultans throughout history. The pavilion, where the sultans watched the sports competitions of the inner boys of Enderunlu and organized conferences used for meetings and negotiations, has survived to the present day as the first example of the style called Turkish rococo with the repairs it has undergone.

The Divanhane, located inside the pavilion, is a section where the sultans sat and divan meetings were held. In this section, discussions on state affairs were held and decisions were taken. It serves a similar function to the divanhouses of Topkapı Palace, the administrative center of the Ottoman Empire. The Sherbet Room is an elegant place where the sultans and their guests consumed refreshing drinks.

Sofa Mosque

In later periods; Çadır Köşkü and Silahdarağa Köşkü were built in the place where Fatih had the Third Place Pavilion built while building Topkapı Palace. During the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, sources indicate that the Sofa Mosque was built along with the Sofa hearth.

Sultan Mahmud II had the building demolished and the Sofa Mosque built in its place in 1809, as the dethronement of Sultan Selim III was planned in the Silahdarağa Pavilion. When Sultan Abdülmecid built the Mecidiye Mansion and the Esvab Room in 1859, he had the masjid demolished again and today’s Sofa Mosque built. From the inscription of the mosque written by Safvet, it is understood that it was built for the officials of the Treasury Chamberlain’s Office and the Treasury Ward to perform their prayers here.

The Sofalılar Quarry, which gives its name to the mosque, is an old organization of the palace. Their wards were located under the Tent Pavilion. The Sofalılar, which can be considered a section of the Bostancı (gardeners), guarded the Fourth and Fifth places and took care of the cleanliness of the Chamber of the Holy House.

Mecidiye Mansion

It is the last building built in Topkapı Palace. It was built by Sultan Abdülmecid in 1859 by Serkis Balyan Kalfa, the architect of Dolmabahçe Palace. Although the pavilion was first called Yeni Köşk, in time it was named Mecidiye Köşkü in reference to Sultan Abdülmecid. It was built on top of the vaulted domed basement floors of the Third Place and Çadır Pavilions. Some of the walls in the basement and the retaining walls further down date from the Byzantine period. After the sultans started to reside in Dolmabahçe and Yıldız Palace, the sultans rested in this pavilion when they came to attend ceremonies such as the julus and the visit to the Holy Palace.

Hekimbasi Room / Chief Lala Tower

During the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror, the square space belonging to the Eastern Roman period was not destroyed and was built on the city wall.

The Hekimbaşı room is a kind of pharmacy named after the Hekimbaşı, who was the head of the 60-70 physicians, kehhaller and surgeons belonging to the Birûn organization of the palace. There were two pharmacies and five hospitals in the palace, one of which was located in the Harem.

In the palace, the treatment of the sultan and the members of the Harem and Enderun was carried out by the physicians, ophthalmologists (kehhaller) and surgeons in the health organization headed by Hekimbaşı. The medicines and preparations to be used in the treatment were prepared by the staff of the Hekimbaşı and especially by the inner boys of the Kilerli Ward. These special mixtures prepared by the Hekimbaşı were usually kept in special inkwells, bowls and bottles.

Abdülhak Molla, who served during the reign of Sultan Abdülmecid (1839-1861), was the last Hekimbaşı of Topkapı Palace. After the sultans stopped living in Topkapı Palace, the Hekimbaşı room was first converted into a meşkhane and then a weapon repair shop. In the early 20th century, the building was restored and materials related to medicine and pharmaceuticals were brought together.

Esvab Room

The clothes worn by the sultans during official ceremonies and the jewelry belonging to these clothes were among the important items carefully preserved in the Ottoman palace. For this purpose, Mecidiye Mansion, one of the most remarkable buildings of the palace, was built. Built in the mid-19th century in the European style, the pavilion has a flamboyant architecture and was used as a place where the sultans’ ceremonial clothes were stored.

The Esvab Rooms, on the other hand, were special rooms used in the Ottoman palace since the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror and reserved for the storage of the sultans’ fabrics, clothes and jewelry. This task, which was initiated by the Dulbent Agha, was eventually carried out by the Esvabcıbaşı and his entourage. Esvab Rooms are carefully protected areas where valuable fabrics and dresses are stored in an organized manner.

These important structures shed light on the rich cultural and historical heritage of the Ottoman Empire. The Mecidiye Pavilion and the Esvab Rooms are known as valuable places that bring important details of the sultans’ clothing and ceremonies to the present day.

Harem and Architectural Sections

Harem, which means “sacred place where no one is allowed to enter” in Arabic, describes private family life in Muslim countries. The word “harem” was used in two different senses. The first refers to the “harem of the sultan”, that is, his family, and the second refers to the place where the family lived. The purpose of the palace harem, which constituted a wing of the capitol staff recruited in accordance with the Ottoman understanding of governance, was not only to form the dynasty, but also to create a state aristocracy by marrying concubines after a disciplined education to the aghas trained in the Enderun school.

The Harem Department of Topkapı Palace was the living quarters of the sultan, the governor sultan, the sultan’s women, their children, sisters and brothers, servant concubines and the Black Aghas, the guardians of the Harem. This group of buildings, which was the private and forbidden place of the dynasty, is an extremely important complex in terms of architectural history, containing examples in the styles of various periods from the 16th century to the early 19th century. Expanding with additions during the reign of each sultan, the Harem today has approximately 300 rooms, 9 baths, 2 mosques, 1 hospital, 1 laundry and many wards.

In the Harem institutionalization, the spaces where all service groups lived were gathered around a courtyard. The podima stone floor concludes at the Sofa with Hearth, the entrance to the sultan’s apartment, emphasizing the sultan’s itinerary.

Cabinet Dome / Harem Treasury / Haremeyn Treasury

The Harem Apartment is an important part of the palace complex of the Ottoman Empire with a rich history. First built during the reign of Sultan Murad III (1574-95), it is one of the private living spaces within the palace. The Harem Department witnessed some of the most powerful and impressive periods of the Ottoman Empire.

In this private space, precious items belonging to the sultans of the palace and other high-ranking officials were preserved. Built-in wardrobes were used to store objects of great value that were used for Surre processions and other important events. Magnificent diamond jewelry, swords adorned with precious stones, gold-plated boxes and many other exquisite items were kept in these closets.

The splendor and luxury of the Harem Apartment is a testament to Ottoman court life. The apartment was decorated with elaborate wood carvings, colorful ceramics and rich carpets. Magnificent halls, spacious courtyards and fountains emphasize the elegance of this space.

The Harem Chamber has witnessed many historical events from the reign of Sultan Murad III to the present day. The social and political decisions made here could affect the fate of the Ottoman Empire. It was also a place that reflected the daily lives of the sultans and other women involved in the harem.

Sofa with Fountain

After the 1665 Harem fire, it has survived to the present day as it was renovated. It was built as the entrance to the Harem under the supervision of the Harem Aghas. The Great Boarding and Curtain Gate connecting the Harem to the Has Garden, the Harem Aghas Masjid and the Tower of Justice are connected to this place by one door each. The riding stone in front of the masjid was built for the sultan to ride a horse, and the sitting benches were built for those on guard duty. The fountain that gave the place its name is today in the pool under the Murad III Has Room. Its walls are covered with 17th century Kütahya tiles.

Kara Agalar Masjid

It was renovated after the 1665 Harem fire. It has a vaulted corridor with windows towards the hall. The walls are covered with 17th century tiles with floral decoration and verses from the Holy Quran. The mihrab has tile panels depicting the Kaaba and its holy places.

Kara Agalar and Kara Agalar Taşlığı

Black Aghas or Harem Aghas were usually selected from Abyssinian origin. Selected from among the eunuchs, the Kara Aghas were taught the rules of the Palace and the Harem and trained in strict discipline. Their main duties were to keep watch at the gates of the Harem, to control the entrances and exits, to escort the carriages and not to let anyone in without permission.

The Girls’ Agha (Dârüssaâde Agha), who was in charge of the Kara Aghas and supervised them, was the highest-ranking official of the Harem. His place in the protocol was after the Grand Vizier and the Sheikhulislam. The Dârüssaâde Aghas, who supervised the foundations of the salâtin as well as the foundations of the Haremeyn, built many mosques, schools and fountains in and outside Istanbul thanks to their high incomes. As they were close to the sultans and their families due to their duties, they were influential in the palace and especially in the state administration in the 17th and 18th centuries.

It is thought that the Kara Ağalar Taşlığı and its surrounding structures were formed during the institutionalization of the Harem in the mid-16th century. This courtyard was the first gizzard of the Harem. Many places where the Harem Aghas lived opened here. The spaces were renovated after the Harem fire of 1665. On the left, behind the porticoes, are the Kara Aghas ward, which was also a place of education, the Darüssaâde Agha’s office and the school for the princes, and on the right, the musahipler’s office and the guardroom. The inscriptions on the façade of the ward include the endowments of Sultan Mustafa IV, Sultan Mahmud II and Sultan Abdülmecid showing the revenues allocated for the eunuchs.

Musahibler Ward

People who were close to the sultans were called musahib. These people were usually knowledgeable, polite, witty and witty, usually chosen by the sultan. Musahibs, as an important part of the court, were the sultan’s trusted advisors and assistants.

Musahibs performed many important duties in the palace. They attended important meetings of the sultan, advised him and contributed to decision-making processes. They also undertook tasks such as conveying the sultan’s orders and managing palace affairs.

There were specially built structures for the accommodation of these musahibs. These buildings consisted of multi-storey spaces made of cut stone. They were usually located close to the courtyard or garden of the palace. These places provided a comfortable and luxurious place for the musahibs to stay and allowed them to be close to the sultan.

These buildings where the musahibs stayed were also used by other important officials of the palace. For example, Hazinedar aga and dwarf aga, who organized the financial affairs of the Harem, also used these places. These people, who were influential in the internal affairs of the palace, played an important role in the administration of the palace together with the musahibs.

The accommodation structures of the musahibs developed and changed over time. The walls, which were covered with tiles in the classical period, were painted on plaster in the 19th century. These changes gave the palace an aesthetically successful and flamboyant appearance. Part of the façade facing the gizzard was decorated with tiles, thus emphasizing the splendor and wealth of the palace.

The duties of the Musahibs and the buildings where they stayed constitute an important part of Ottoman palace culture. Responsible for the internal affairs of the palace, they were knowledgeable and talented people who had gained the trust of the sultan. Musahibs were an important element in the functioning of the palace and were part of the administrative system of the Ottoman Empire.

Black Aghas Ward