Kimbell Art Museum (Texas)

Commissioning and architectural summary

Kimbell began as a civic promise: The Kay and Velma Kimbell Foundation aimed to create not just a place to store a collection, but a “first-class” museum. After Kay Kimbell’s death, the foundation formalized its intent in 1966 with a policy statement and planning efforts led by founding director Richard F. Brown, and then moved to achieve this goal. Louis I. Kahn took on the task in October 1966, and the museum opened in October 1972, embodying an approach in which architecture was considered part of the institution’s identity, rather than an afterthought. The project brief was unusually clear about atmosphere: Brown explicitly stated that “natural light must play a vital role in illumination,” thus transforming daylight from a convenience into an ethical imperative. This focus led Kahn to design a museum with modest, controlled grandeur; one where the building would not overshadow the art or the visitor, but would quietly elevate both. In other words, the program was not a list of rooms, but a stance on how culture should be felt upon entering.

The architect’s philosophy behind the design

Kahn’s guiding question was famously simple: “What does this building want to be?” For Kimbell, the answer begins with the room and then transforms into a “family of rooms” created through classical proportions, repetitions, and variations, allowing the visitor to sense the order without being lectured. The structure is not hidden; it is an idea made visible, so quiet it could disappear into use. Even the vault geometry reflects a philosophy: the cycloid presents a monumental appearance, yet its gently rising edges keep the scale human, as if held steady by a large hand rather than lifted to be impressive. Kahn wanted permanence without heaviness and clarity without coldness, so the building teaches you how to look before you look at a painting.

The concept of light as the primary design element

At Kimbell, light is treated as a building material with its own structure and rules. Daylight enters through narrow skylights along the cycloidal vaults, then encounters wing-shaped perforated aluminum reflectors, which soften the light and create that famous silvery sheen on the concrete. The result is not a theatrical spotlight, but a quiet, variable luminosity that makes the art feel fresh, as if the room were breathing. This “natural” light is also a feat of high engineering, because museums must protect the works they display. Lighting designer Richard Kelly helped resolve the conflict between the beauty and danger of daylight, designing a reflector system that redirects and diffuses the sun while eliminating the risk of ultraviolet rays, creating a subtle connection to the time of day. The building does not block the outside world; it transforms it into a safe, legible glow.

The influence of classical and ancient architecture

Kahn clearly linked the museum to “the splendor of Rome” not by copying its decorations, but by reviving the emotional logic of its arches, vaults, and porticos. Kimbell’s long bays and courtyards feel like a pre-constructed modern ruin; a place where mass and void are balanced, where your body understands the plan before your mind names it. Classically sensitive: measured, durable, and confident enough to remain quiet. Kimbell Art Museum References delve even deeper into ancient utility: Kahn admired Roman arches and storage structures, even Egyptian granaries that solved the problems of gravity, shadow, and time with simple forms. This lineage explains the simplicity of materials and the dignity of details, using concrete, travertine, and oak like a limited palette in a painting. The past is present here not as nostalgia, but as discipline.

Architectural Features and Spatial Arrangement

The use of cycloid vaults and vaulted wings

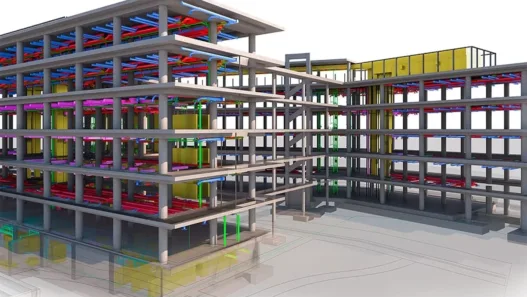

Kahn’s museum consists primarily of a series of repeated cycloid “rooms” that are essentially replicated and transformed into architecture: sixteen barrel vaults arranged in parallel strips (6-4-6), each measuring approximately 100 x 20 feet. The cycloid curve is not merely a beautiful cross-section; it is structurally reliable, a geometry that can be read as monumental without overwhelming visitors. The arches are reinforced with concrete supports and tension cables, as they are cut at their upper sections for skylights, making the serene ceiling also an engineering tool. Outside, the same arch logic transforms into porticos and the “wings” of the enclosed space, presenting the building’s internal layout as a public threshold.

Natural lighting system: skylights and light reflectors

Light enters through the narrow roof windows at the top of each cycloid vault, then spreads softly and evenly across the concrete via wing-shaped perforated aluminum reflectors. Richard Kelly Grant This is gentle daylight: it remains responsive to the variability of the outside world, yet prevents the harshness of direct sunlight that could damage paper and textile products. Richard Kelly Grant Richard Kelly’s contribution extends to the details that enable tranquility, from UV filtration to reflective materials and perforated patterns that adjust contrast. Richard Kelly Grant Courtyards are also part of the lighting system; by leaving space between the vaults, they transfer the reflected brightness to the interior spaces and make “museum time” feel like real time.

Material palette: concrete, travertine, wood, metal

Kimbell’s palette is deliberately sparse and highly tactile: concrete, travertine, white oak, metal, and glass, selected with tones close to each other so that light becomes the primary “color.” Concrete here forms both the structure and the atmosphere; the vaults are poured and finished for surface quality, then brightened by the reflector system above. Travertine lends an old-world tranquility to the floors and walls, while white oak warms the experience at eye level, ensuring the building never feels clinical. Metal appears more like precision than decoration; at the edges of the skylights, in the reflectors, and in the fixtures, it acknowledges that the building is, in part, a finely crafted device.

Layout: galleries, courtyards, porticos, and circulation areas

The plan reads like a disciplined rhythm: on the west facade, three 100-foot bays, each expressed as a portico with a cycloid vault, the central entrance recessed and glazed. Inside, the vaulted sequence is interrupted by three courtyards, which divide the museum into breathable sections and allow you to find your way without directional signs. The arch modules extend deep behind the porticos (five behind the side bays, three behind the center), so circulation feels like moving within a long, measured sentence rather than jumping between rooms. Even the daylight strategy shapes the layout; the arched galleries are designed with a north-south orientation, so light arrives as a consistent and functional presence.

Integration of structures and service areas/service providers

At Kimbell, the “service areas” are clearly visible: vaulted galleries where art and daylight meet, where the ceiling is not a covering but a character. However, the building’s intelligence lies in how it conceals its support systems without denying them: mechanical services are hidden where the vaulted edges almost meet, and the structural geometry is used as a place to conceal necessity. Lighting is treated in the same way and is designed as a single integrated concept consisting of “shell, skylight, and fixture” rather than ceiling and equipment. Richard Kelly Grant Thus, the structure, light, and services do not compete with each other; they collaborate and leave visitors with a rare feeling that the museum is both inevitable and gentle.

Legacy, Impact, and Subsequent Expansion

Acceptance and influence in modern architecture

Kimbell has always been regarded as more than just a successful museum: it became a reference point, the “center of modern architecture,” and is still defined by the museum as one of the outstanding achievements of the modern era. This reputation was cemented in 1998 when it received the AIA Twenty-Five Year Award, given to buildings whose impact and excellence endure for decades. The Kimbell Art Museum’s influence is quiet but felt everywhere: Architects come here to study how proportion, structure, and daylight can create authority in an unassuming way, and they carry what they learn into projects far beyond museums.

How did the building change museum design traditions?

Kimbell demonstrated that daylight and conservation are not mutually exclusive when light is shaped, filtered, and treated as an architectural material, thereby helping to redefine what a “suitable” museum could be. At the opening, founding director Richard F. Brown praised this museum as “what every museum seeks,” citing its seamless floor and “perfect lighting,” which redefined flexibility and clarity as the true luxury of the exhibition space. The Kimbell Art Museum Kahn designed a series of tranquil rooms where the rhythm of the structure and the atmosphere of light take precedence over a dark, artificially lit box, making viewing art feel like a daily human act rather than a staged event.

Expansion: the addition of a new pavilion and its dialogue with the original structure

In the subsequent expansion project, respect took precedence over imitation: Renzo Piano’s pavilion is located approximately 65 meters west of Kahn’s building and, while preserving the original form intact, creates a new “campus” dialogue on the lawn. Piano produced a parallel work to Kahn’s without imitating him; he chose a similar height, used natural light, employed concrete alongside glass and wood, and then divided the pavilion into two parts connected by a glass passageway, achieving a light and uncluttered appearance. Opened to the public on November 27, 2013, the structure was clearly framed as a dialogue between old and new, even doubling the gallery’s capacity and improving visitors’ access to the original west facade, while managing to remain unobtrusive by concealing approximately half of its footprint underground.

The enduring importance for today’s architects and visitors

Kimbell remains relevant because its fundamental issues never grow stale: how can we soften the light, how can we make the structure legible, how can we make the museum feel dignified without making it feel noisy. For visitors, the lasting impact is physical and immediate: rooms that feel neither valuable nor exhausting, where daylight softens rather than demands attention. For architects, it continues to serve as a lesson that good buildings do not need novelty to be new, but rather consistency, so that the space can continue to teach even after the initial applause has faded.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.