Cardboard Cathedral— Shigeru Ban

The 2011 Christchurch earthquake and the destruction of the old cathedral

In February 2011, the devastating earthquake that struck Christchurch severely damaged the city’s Anglican cathedral, destroying not only stone and wood but also a shared civic symbol. Shigeru Ban When such a symbolic structure is destroyed, the loss is not only religious but also urban and emotional: the horizon becomes silent, rituals lose their place, and grief becomes spatial. The Cardboard Cathedral begins here as an answer to an unavoidable question for Christchurch: When a city’s heart is fenced off, what does the city gather around?

The necessity of a temporary cathedral for the Anglican Diocese of Christchurch

The project was not, in the narrow sense, a “temporary shelter”; it was a temporary cathedral, a temporary space where the bishopric could continue its functions and remain visible. Public life had to continue alongside worship, because disasters do not just destroy buildings; they also destroy programs, communities, and trust. Therefore, while long-term work continued in the background to rebuild the original cathedral, the project was expanded into a civil interior space that served as an Anglican cathedral “for everyone”: Christchurch Cathedral.

Shigeru Ban and the implementation of the philosophy of humanistic design

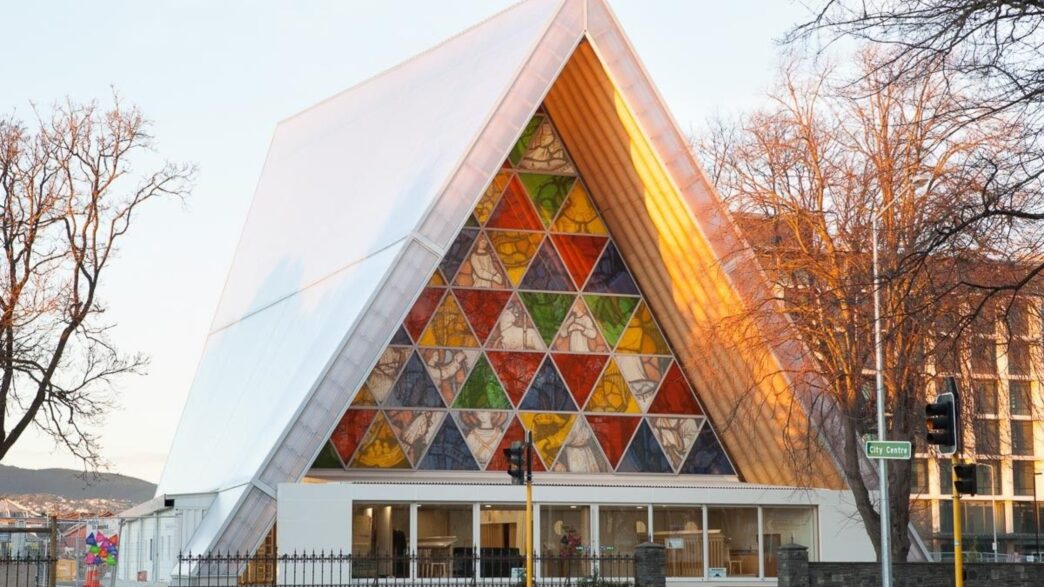

Shigeru Ban was asked to respond because he treats emergencies not as side projects but as real architectural work in his career. Shigeru Ban is known for using recyclable paper tubes for disaster relief structures. Because with serious design, dignified structures can be built from existing, inexpensive, and portable materials. In Christchurch, this ethic becomes legible as a building: a calm, sensitive A-frame form that rejects the usual hierarchy between “proper” architecture and “temporary” survival.

Site selection: from the site of the former St John the Baptist Church to the new location at Latimer Square

The cathedral rises on the site of the old St John the Baptist Church in Latimer Square, just a few blocks away from the damaged ChristChurch Cathedral. Close enough to remain in the city’s memory, yet far enough to distance itself from the weight of destruction. This choice is significant: by shifting from a “central” monumental square to a restored corner, it allows healing to become local and walkable. St John’s had been demolished due to earthquake damage, and the new building was constructed on this cleared site, acting as a bridge between loss and continuity.

Design and Structural Innovation

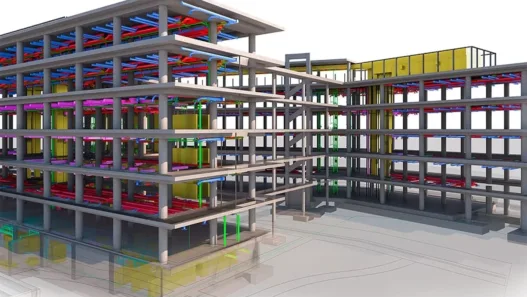

Cardboard tubes, wood, and steel usage: material selection and rationale Ban’s “cardboard” is actually a disciplined hybrid: 98 paper tubes form the roof and side walls, but each tube is reinforced with laminated wood inserts and the entire structure is fixed with steel. The rationale is both practical and philosophical: local production makes the building quick and understandable, while the low-status material sends a message to the public that prestige is not exclusive to stone. The cladding and fire resistance do more than just protect the tubes; even if the structure appears extremely ordinary, it restores the city’s confidence in this area.

Cardboard tubes, use of wood and steel — material selection and rationale

Geometric derivation: establishing a connection with the proportions of the original cathedral

The cathedral’s geometry is not a random A-frame symbol; its angles are derived from the original ChristChurch Cathedral’s plan and heights. Shigeru Ban This connection is important because it lends a quiet familiarity to the new form, like hearing a melody in a new instrument. Ban explains that he started with an economical A-frame, then steepened the triangles to create a trapezoid with dimensions directly analyzed from old drawings. ArchitectureAu The result is a structure that feels “accepted” not through imitation, but through proportional memory.

A-frame / trapezoidal plan and altar reaching a height of 21–24 m

The plan tapers like a funnel and forms a clean triangle in cross-section, so the space naturally slopes forward and upward, toward the altar. This tapering is not just geometry, but also choreography: as the walls draw closer together, the roof rises to a height of approximately 79 feet (about 24 m), transforming the Gothic impulse into a single, decisive movement. At the same time, the repeated portal-like frames create a rhythm at a height of 21 m, transforming simple tubes into a series of structures you can feel with your body.

Integration of shipping containers and polycarbonate roof for base and storage

Eight 20-foot shipping containers stand like heavy bases, forming the side walls and anchoring the lighter tubular roof above. Shigeru Ban This is an organized tectonic narrative: mass at the base, air and light above, a stability you can grasp at a glance when the city tires of invisible risks. The polycarbonate cladding protects the structure from weather while keeping the building bright, thus transforming the cladding from a hard boundary into a soft filter. Interior lighting strategy: the spaces between the tubes and stained glass create ambiance Light enters through the deliberate gaps between the tubes, transforming daylight into delicate vertical lines that calm the interior without making it feel dim. Material Zone Polycarbonate sheets soften the brightness, so the space appears like a lantern rather than a glass box. At the entrance, the stained glass wall made of triangular glass panes reflects the lost rose window by dividing it into colors and memories rather than copying it.

Interior lighting strategy — creating ambiance with the spaces between tubes and stained glass

Social, Cultural, and Architectural Impact

Functionality: from temporary cathedral to community, concert, and event venue

The Cardboard Cathedral, built as the “temporary home” of the cathedral community, was not only meant to carry symbolic meaning but also had to immediately fulfill its function. Christchurch Cathedral’s interior space, which seats 700 people, is the size of a real town hall, allowing it to host not only services but also concerts, recitals, and various events. Christchurch Cathedral Shigeru Ban This mix is important because after a disaster, a city needs not only shelter but also rehearsal spaces for normal life: music, gatherings, public speeches, simply coming together. Christchurch Cathedral Message of resilience: Symbolizes recovery and hope for Christchurch The building transforms “recovery” into something you can enter, a place where grief ceases to be an abstract headline and becomes a shared atmosphere. The Guardian, in its report on Christchurch after the earthquake, clearly stated that the cardboard cathedral had become a symbol of “carrying on with life,” a kind of optimism that is not cheerful, but simply necessary. The Guardian’s transparency and modest materials offer a silent promise: strength does not always look like stone, and faith can be rebuilt as a temporary act repeated every day.

Message of resilience — Symbolizing recovery and hope for Christchurch

Acceptance by the architectural community and the public; the debate between temporary value and lasting value

It gained worldwide attention from an architectural perspective and, in terms of reconstruction, was cited as an example of “international acclaim” that helped keep civilian life active during the reconstruction process, along with other temporary structures. Lincoln Land Policy Institute However, this reception sparked a deeper debate: While church officials characterized it as a temporary structure, Ban completely opposed the hierarchy and emphasized that if the space is good, there is no real difference between temporary and permanent. This debate reflects the Christchurch cathedral conflict, where decisions regarding demolition, heritage, cost, and identity became not only technical but also public and emotional.

Heritage: Its impact on disaster relief architecture and sustainable design approaches

The lasting impact of the Cardboard Cathedral stems not from its being made of paper, but from its demonstration that “lightweight” materials can carry significant social meaning when carefully designed and constructed. As noted in the Pritzker Prize citation, Ban’s broader work on disasters treats recyclable paper tubes as legitimate structural elements because they are local, inexpensive, portable, and resistant to water and fire. In this sense, the cathedral functions as a full-scale demonstration project for Ban’s humanitarian aid toolkit. The same logic applies to paper tube partitions that restore privacy and dignity in emergency shelters. Shigeru Ban Heritage is a design approach: Sustainability is not decoration; it is the ability to build quickly, responsibly, and beautifully at a time when the world is least prepared to wait.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.