To stand within a great English cathedral is to be in a library where the books are made of stone and glass. Each arch, window, and vault tells a story of faith, engineering, and artistry spanning centuries. But how does one learn to read this complex language? For generations, students of architecture have sought a key to unlock these stories, a system to bring order to the beautiful chaos of five hundred years of construction.

That key was forged by the 19th-century architect and scholar, Edmund Sharpe. In his masterwork, The Seven Periods of English Architecture, Sharpe argued that the existing classifications were inadequate, failing to capture the nuance and pivotal moments of stylistic change. With the precision of an architect and the clarity of a dedicated teacher, he presented a new framework—a seven-part system that remains one of the most logical and useful tools for understanding English architectural history.

This guide aims to distill the essence of Sharpe’s brilliant work, making his seven-period system accessible to a modern audience. By using comparative tables and focusing on the defining characteristics he identified, we can learn to see these magnificent buildings as living documents of an ever-evolving art form. Our journey through this system is a tribute to Sharpe’s scholarship, and all credit for the detailed observations that follow belongs to him.

Understanding the Architectural Compartment

To compare styles across centuries, Sharpe focused on a single, repeating unit of a cathedral’s main wall: the Compartment (or Bay). This is the section from the center of one great pier to the next. He observed that this compartment is almost always divided vertically into three distinct stories. Understanding these three levels is fundamental to reading the architecture:

- 1. The Ground-story (or Pier Arcade): This is the lowest level, consisting of the massive piers and the great arches that separate the central nave or choir from the side aisles.

- 2. The Triforium (or Blind-story): The middle story, located above the aisle roof. It can range from a large, open gallery to a small, decorative band of “blind” (un-glazed) arcading. Its changing size and importance are a crucial indicator of style.

- 3. The Clere-story (or Clear-story): The upper story, which rises “clear” of the surrounding roofs. This is the primary source of light for the central space, and its windows are one of the most telling features of any period.

By observing how the form, proportion, and decoration of these three stories change over time, we can accurately identify the architectural period of any part of a building.

The Seven Periods: A Comparative Overview

This table provides a high-level summary of Sharpe’s system, allowing for a quick, at-a-glance comparison of the defining features of each era.

| Period Name | Dates | Key Characteristic | Dominant Arch |

| I. Saxon | pre-1066 | Early, simpler Romanesque forms. | Round |

| II. Norman | 1066-1145 | Overwhelming mass and universal use of the heavy round arch. | Round |

| III. Transitional | 1145-1190 | Pointed arches for structure, co-existing with round arches for decoration. | Pointed & Round |

| IV. Lancet | 1190-1245 | Tall, narrow, unadorned pointed windows (lancets) without tracery. | Pointed |

| V. Geometrical | 1245-1315 | Invention of window tracery using perfect circles and compass-drawn shapes. | Pointed |

| VI. Curvilinear | 1315-1360 | Flowing, flame-like window tracery based on the reverse “Ogee” curve. | Pointed & Ogee |

| VII. Rectilinear | 1360-1550 | Rigid, grid-like design with an emphasis on vertical and horizontal lines. | Pointed & Four-Centred |

An In-Depth Journey Through the Seven Ages

Part One: The Romanesque Foundation

Defined by the strength and solemnity of the round arch, this era represents the architectural language England shared with continental Europe before the great Gothic revolution.

I. The Saxon Period (pre-1066)

Sharpe notes that a comprehensive analysis of the Saxon cathedral is impossible, as no complete example survives. The fragments that remain, primarily in parish churches like St. Wistan’s, Repton, or the tower of Earl’s Barton, hint at an architecture of sturdy simplicity. It was the native prelude to the continental style that would soon arrive with overwhelming force.

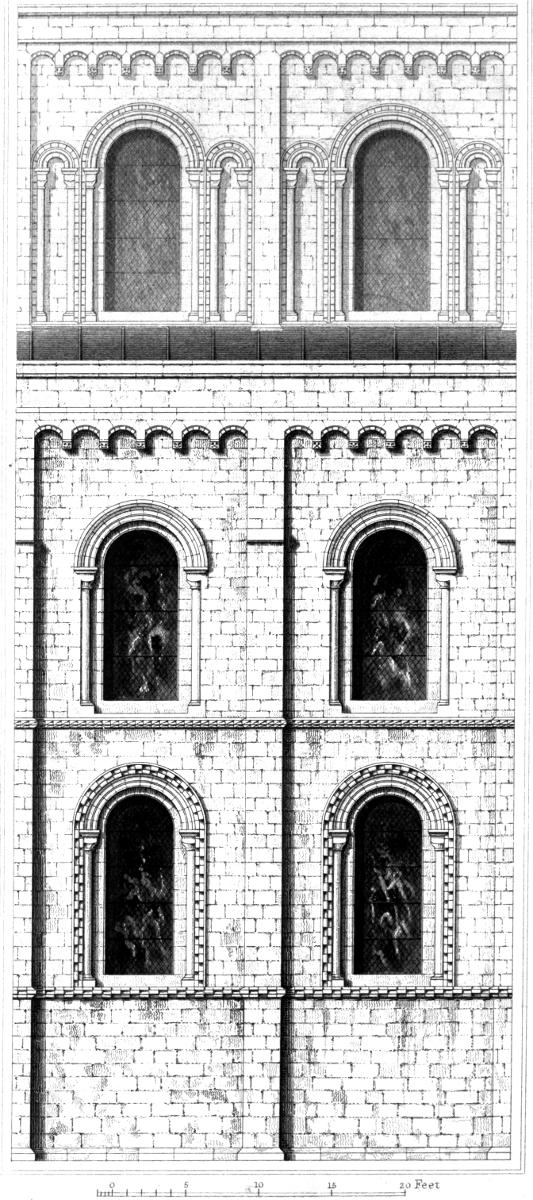

II. The Norman Period (1066 – 1145)

Principal Characteristic: The universal and uncompromising use of the massive, round arch in every part of the building.

The Architectural Philosophy: This is an architecture of conquest and control. The Norman cathedral was a fortress of God, built to inspire awe and declare the permanence of a new order. It is defined by immense scale, overwhelming mass, and a powerful, horizontal rhythm.

- Exterior Analysis: The walls are immensely thick, built of small, regular stones, with a simple projecting base-course. Buttresses are wide but so shallow they are mere “pilaster strips,” offering more visual division than structural support. The roofline is typically marked by a Corbel-table—a series of small, carved stone brackets supporting a projecting course. Windows are characteristically low and broad, small openings in the vast expanse of wall, often with a single shaft in the jamb.

- Interior Analysis: The impression is one of ponderous, solemn grandeur. The main arcade is carried on enormous, stout cylindrical columns or huge rectangular piers with attached semi-circular shafts. These piers are sometimes scored with bold incised patterns—chevrons (zig-zags), spirals, or lozenges, as seen magnificently at Durham Cathedral. Capitals are rudimentary cubical blocks, square on top and rounded at the bottom to meet the circular pier, known as cushion capitals. The great pier-arches are heavy, with square-edged orders or thick, rounded mouldings. Above this, the Triforium (the middle story) is a vast, shadowy gallery, often featuring a single, massive round arch almost equal in span to the pier-arch below it. The Clere-story (upper window level) is distinguished by a wall passage, an internal gallery set in the thickness of the wall, with an arcade of three arches on the interior face, the taller central one framing the window.

- Key Ornamentation: Decoration is geometric and forceful. The chevron is the ubiquitous ornament, often deeply carved in multiple concentric rows around arches. Other common motifs include the billet (a series of small cylindrical or square blocks) and the star.

- Prime Examples: The naves of Ely and Peterborough Cathedrals, the transepts of Winchester, and the entire structure of the White Chapel in the Tower of London.

III. The Transitional Period (1145 – 1190)

Principal Characteristic: The contemporaneous use, in the same building, of both round and pointed arches.

The Architectural Philosophy: This is the style of an age in conflict, a fascinating architectural “battle of the forms.” Builders had discovered the structural genius of the pointed arch—its ability to direct weight more efficiently downwards—but were aesthetically reluctant to abandon the familiar harmony of the round arch. The result is a dynamic, experimental style where austerity gives way to aspiration.

- Exterior Analysis: The building begins to lighten. Buttresses gain greater projection, and windows become more elongated. The crude corbel-table is replaced by a more refined, regularly moulded Cornice. The walls, while still substantial, are no longer as oppressively thick.

- Interior Analysis: The revolution is most apparent inside. The heavy cylindrical column disappears, replaced by piers composed of a lighter cluster of shafts. Sharpe notes the appearance of the pear-shaped shaft, a key transitional feature. The capitals are the most telling detail: still square on top (the abacus), the bell of the capital is a concave shape, often adorned with a delicate, curled leaf or “small volute.” The pointed arch makes its decisive appearance, but with a specific logic: it is used for Arches of Construction (the main pier-arches and the primary ribs of the vault), while the round arch is retained for Arches of Decoration (the windows, doorways, and the triforium arcade).

- Key Ornamentation: The bold Norman chevron still appears, but a new, more delicate chevron moulding, peculiar to this period, also emerges. Mouldings in general become lighter, more numerous, and more complex.

- Prime Examples: Ripon Cathedral’s choir, the nave of Malmesbury Abbey, and the later work at Fountains Abbey are textbooks in this fascinating style.

Part Two: The Gothic Ascendancy

With the pointed arch now triumphant, English architecture entered a new phase of grace, light, and verticality. Sharpe brilliantly observed that the most reliable way to chart the course of Gothic is to follow the evolution of the window.

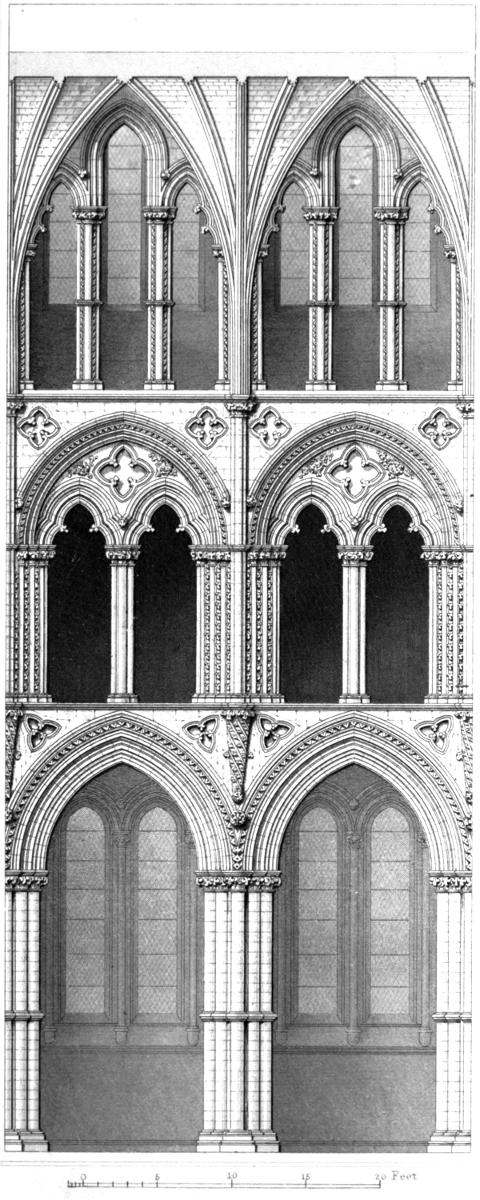

IV. The Lancet Period (1190 – 1245)

Principal Characteristic: The use of tall, narrow, acutely pointed windows (lancets), without tracery, used singly or in arranged groups.

The Architectural Philosophy: This is the first pure, unadulterated English Gothic. Its spirit is one of soaring, confident faith and elegant simplicity. The style sheds all Norman weightiness, striving for height and linear grace. Beauty is achieved through perfect proportion, repetition, and the dramatic interplay of light and shadow.

- Exterior Analysis: The building becomes a composition of strong vertical lines. Buttresses are deep, divided into stages, and often capped with a simple pyramidal pinnacle. For the first time, Flying Buttresses span the aisle roofs, elegantly transferring the thrust of the main vault. Windows are arranged in dramatic compositions—couplets, triplets, or groups of five or seven, as in the “Five Sisters” window at York Minster.

- Interior Analysis: The inside is a forest of slender shafts. Piers are typically a central column surrounded by a cluster of smaller, detached shafts, often of dark, polished Purbeck marble, which are frequently “banded in the middle” for stability and visual effect. Mouldings are exceptionally deep and finely wrought, with a characteristic pattern of alternating rounds and deep, narrow hollows that create sharp lines of shadow. The Triforium arcade is now a delicate screen of smaller, pointed arches, often containing subordinate trefoiled or quatrefoiled piercings. The vaulting is a simple quadripartite or sexpartite ribbed vault, rising sharply to a point.

- Key Ornamentation: The signature ornament is the dog-tooth, a small, four-leafed pyramid carved in continuous rows within the hollows of the mouldings.

- Prime Examples: Salisbury Cathedral is the quintessential Lancet building. The Presbytery of Ely Cathedral and the nave of Lincoln Cathedral are other supreme examples.

V. The Geometrical Period (1245 – 1315)

Principal Characteristic: The invention of bar tracery, with window patterns composed of simple, perfect geometric forms, especially the circle.

The Architectural Philosophy: The Lancet style’s austerity gives way to a more intellectual, ordered beauty. The solid wall space between lancets was opened up, and the window head became a canvas for the mason’s skill with a compass. This is an architecture of rational, geometric harmony, celebrating divine order through the perfection of form.

- Exterior Analysis: Proportions become grander. Buttresses are often more elaborate, with gabled and crocketed canopies on their faces. Windows grow much larger, now divided by stone mullions into two, three, or more lights, with the head filled with tracery of foliated circles, trefoils, and quatrefoils.

- Interior Analysis: The pier design is consolidated; the detached shafts of the Lancet period merge into a single, solid pier of a complex, moulded section, often on a “spherical triangle” plan. The Triforium begins its decline; Sharpe notes it becomes “greatly reduced in size and prominence, and is made entirely subordinate to the Clere-story.” In some cases, it becomes a simple low, foliated arcade. The inner arcade of the Clere-story passage disappears completely, replaced by a single arch spanning the whole bay.

- Key Ornamentation: The dog-tooth vanishes, replaced late in the period by the ball-flower—a globular, three-petalled flower enclosing a small ball. Foliage carving becomes much more naturalistic, with identifiable species like oak, ivy, and maple rendered with exquisite realism.

- Prime Examples: The “Angel Choir” at Lincoln Cathedral, the chapter houses of Westminster and Salisbury, and the nave of Lichfield Cathedral.

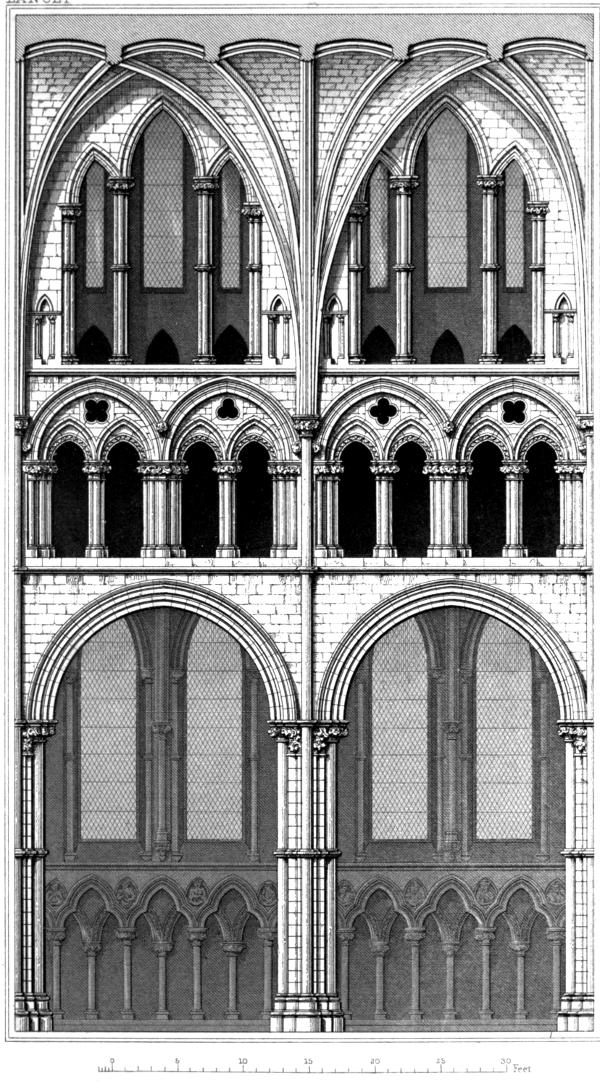

VI. The Curvilinear Period (1315 – 1360)

Principal Characteristic: Flowing, flame-like window tracery based on the reverse or Ogee curve.

The Architectural Philosophy: This is the second crucial style Sharpe separated from the general “Decorated” category. The rational, static geometry of the previous era dissolves into movement, passion, and opulent grace. The rigid line of the compass is abandoned for the sinuous, free-flowing line. This is the most lyrical and flamboyant of all English Gothic styles.

- Exterior Analysis: The Ogee curve is everywhere—in the main lines of the window tracery, in the canopies over niches and tombs, and even in the profile of the mouldings. Tracery patterns become incredibly complex and varied, creating flowing, reticulated (net-like), or flame-like designs. Parapets are often pierced with flowing quatrefoils.

- Interior Analysis: The sense of flow continues inside. Piers are often set on a diamond-shaped plan, and a key feature emerges: continuous mouldings, where the arch mouldings flow uninterrupted down the pier to the ground without the intervention of a capital. The Triforium virtually disappears, often reduced to a band of panelling below the Clere-story window. Vaulting becomes much more complex, with the addition of intermediate (tierceron) and linking (lierne) ribs creating intricate, star-shaped patterns on the ceiling.

- Key Ornamentation: Foliage becomes less naturalistic and more stylized, with distinctive “crumpled” or “seaweed” forms. The small, square four-leafed patera is a common decorative motif.

- Prime Examples: The east window of Carlisle Cathedral, the choir of Ely Cathedral (the three eastern bays), and the south transept of Chester Cathedral.

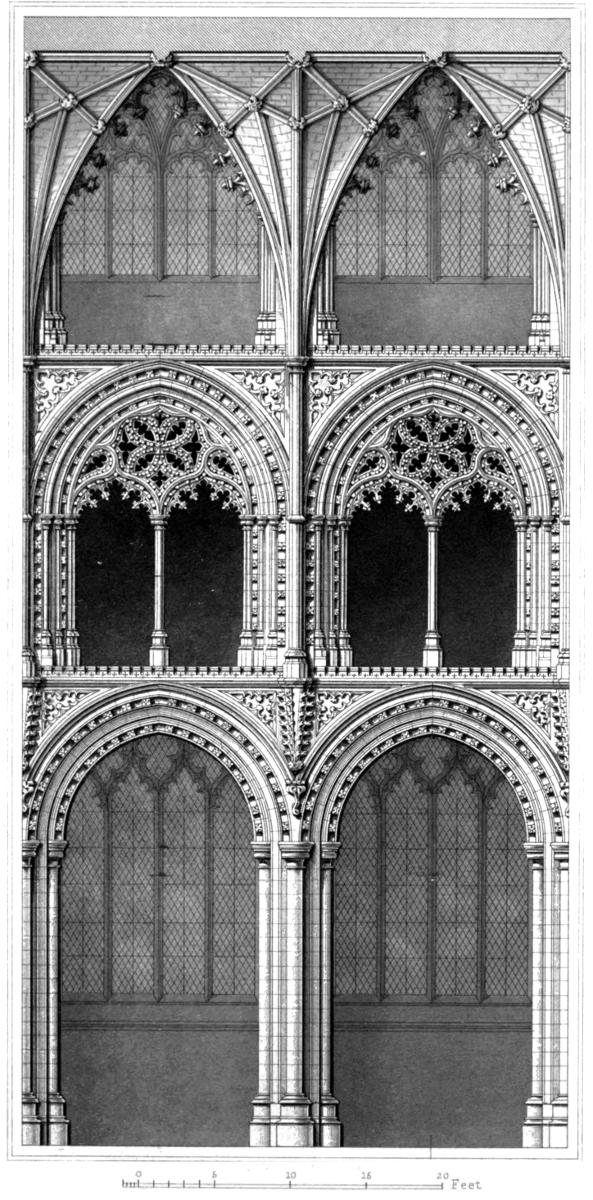

VII. The Rectilinear (or Perpendicular) Period (1360 – 1550)

Principal Characteristic: A strict emphasis on strong vertical and horizontal lines in tracery, panelling, and overall design.

The Architectural Philosophy: A uniquely English style, it was a dramatic reaction against the flowing excesses of the Curvilinear. It is an architecture of immense, light-filled spaces, structured by a rigid grid of divine order. The goal was to create soaring, unified interiors where walls dissolved into vast, luminous screens of stone and glass.

Prime Examples: King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, is the supreme achievement of the style. The choirs of Gloucester and York Cathedrals are magnificent earlier examples, and Henry VII’s Chapel at Westminster Abbey is its final, most ornate expression.

Exterior Analysis: The entire character of the window changes. The vertical stone bars (mullions) no longer branch into flowing curves but run straight up to the main arch, often intersected by horizontal bars (transoms), giving larger windows the appearance of a “huge gridiron.” Walls, especially in richer buildings, are completely covered in rectangular stone panelling.

Interior Analysis: The interior becomes a single, unified vertical space. The Triforium is now completely suppressed, its place taken by a continuation of the Clere-story’s panelling down to the top of the main arcade. This creates a vast, two-story elevation of arcade and window. Piers are tall and slender, with shallow mouldings that often continue uninterrupted around the arch. The most spectacular innovation is fan vaulting, where ribs of equal curvature radiate from the supporting shaft, creating a breathtaking, cone-like effect. The flattened four-centred or Tudor arch becomes a hallmark of the later period.

Key Ornamentation: Ornaments include the Tudor Rose and stylized, flat square leaves. Grotesque sculptures and gargoyles become common on cornices.

Detailed Architectural Comparison Across the Gothic Eras

To see the evolution in finer detail, this table compares key architectural elements across the four great Gothic periods.

| Architectural Element | IV. LANCET (1190-1245) | V. GEOMETRICAL (1245-1315) | VI. CURVILINEAR (1315-1360) | VII. RECTILINEAR (1360-1550) |

| Window Tracery | None. Simple, pointed lancets used singly or in groups. | Bar Tracery Invented. Patterns based on perfect circles, trefoils, quatrefoils. | Flowing Tracery. Complex, flame-like patterns based on the S-shaped Ogee curve. | Grid-like Tracery. Strong vertical mullions and horizontal transoms. |

| Piers | A central column surrounded by a cluster of slender, detached shafts. | Detached shafts merge into a single, solid pier of complex moulded section. | Slender, diamond-shaped plan. Mouldings often flow continuously down to the floor. | Tall, thin, with shallow mouldings that are often continuous with the arch. |

| Vaulting | Simple, acute quadripartite or sexpartite ribbed vaults. | Still simple, but with more richly carved bosses at rib intersections. | Complex Lierne Vaults. Extra decorative ribs (liernes) create star-like patterns. | Fan Vaulting Invented. Cones of stone ribs radiate upwards in a fan shape. |

| Key Ornament | Dog-tooth. A small, pyramidal four-leafed flower. | Ball-flower. A globular, three-petalled flower. Highly naturalistic foliage. | Crumpled, “seaweed-like” foliage. The small, square “patera” flower. | Tudor Rose. Flattened, stylized foliage. Rectangular panelling on walls. |

| Triforium | A prominent and open arcade of pointed arches. | Reduced in size and importance, becoming subordinate to the Clere-story. | Almost entirely disappears, often replaced by a decorative panel or band. | Completely Suppressed. The Clere-story window extends down to the main arcade. |

Conclusion

In this journey through Edmund Sharpe’s seven periods, we have traveled from the heavy, earthbound fortress of the Norman era to the soaring, light-filled glass house of the Rectilinear style. We have seen the arch transform from a simple semi-circle into a sharp, aspiring point, and then flatten into the broad, elegant Tudor arch. We have witnessed the solid wall of the Normans first pierced by slender lancets, then opened into glorious geometric patterns, then dissolved into a flowing web of stone, and finally organized into a vast, ordered grid.

Edmund Sharpe provided a logical framework, a key to a locked library. His system empowers us to look with understanding, to see the subtle and profound changes that mark the passage of time and the evolution of human creativity. The next time you stand within one of these magnificent structures, listen to the echoes of the past, look closely at the story told in its stones, and you will hold the key to reading its story for yourself.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.