This article is an independent version of the article published in this issue of DOK Architecture Magazine. You can access the entire magazine via this link:

We often talk about free will as if it were a divine right. However, in design, free will is a privilege that is earned through context, constraints, and care.

Free will is a concept that has been increasingly used in recent times, along with humanity’s growing selfishness. As we have evolved as a species, we have begun to create reasons to justify our choices. However, it should not be forgotten that every choice we make is a product of our previous choices.

Nihilism essentially says that “everything is meaningless.”

Although this is an expression of the emptiness of the world and our actions, some interpret it as a relief.

However, you may identify more with nihilism when your life is falling apart, and with the latter when everything is going well. The opposite may also be true.

So-called free will resists revealing itself depending on how you interpret this expression.

However, there is still hope. It is what keeps people going. Perhaps it is the last resort for maintaining mental health. A belief so strong that it can defy logic.

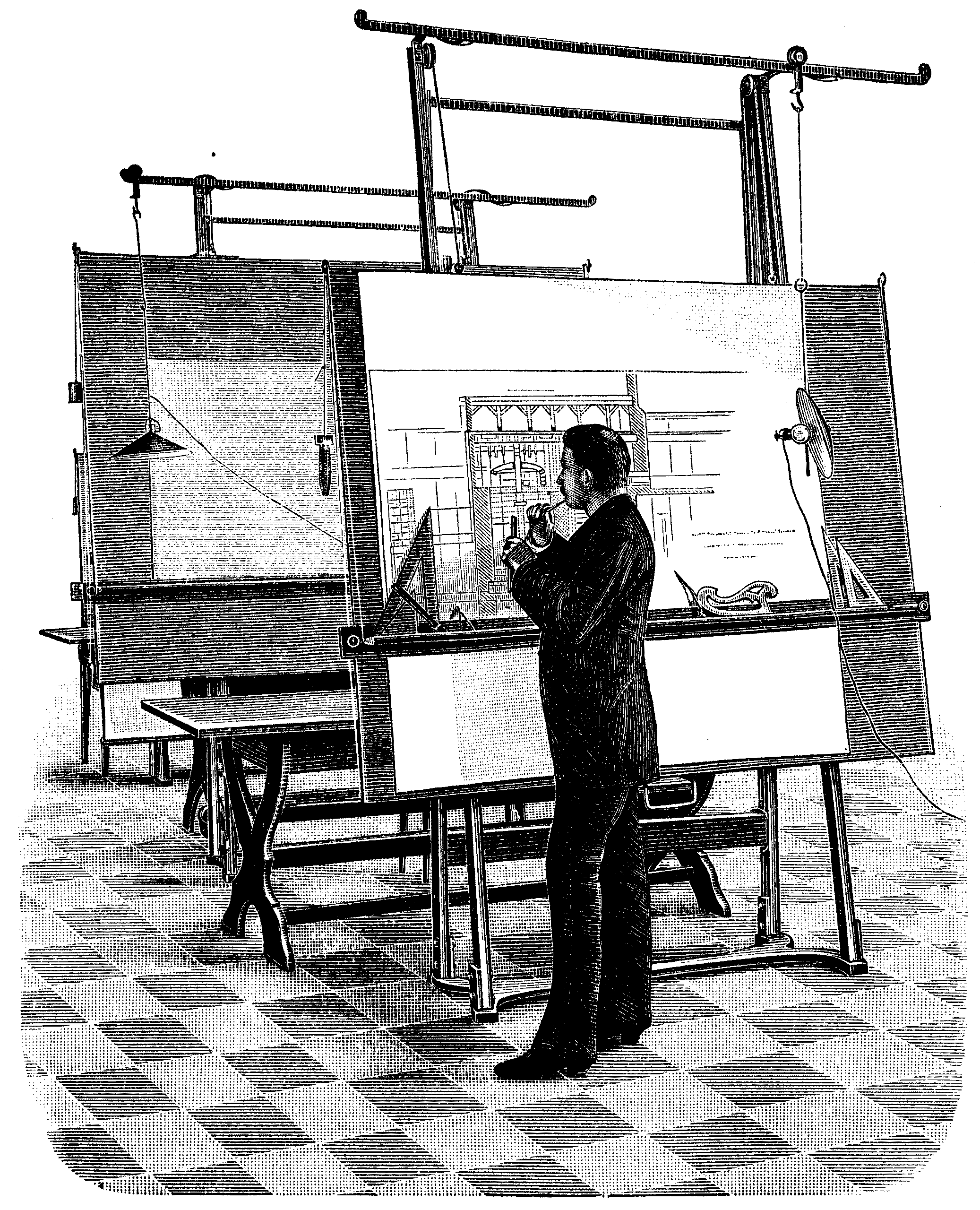

As designers, we can feel free within the constraints and requirements of a building’s code. Often, we use these constraints to our advantage and bend them. Or perhaps we use them to create a unique building that fits the shape of the given site. Choosing which color to use on the walls or which direction the main facade should face is just the tip of the iceberg when discussing free will.

While brutalism forced people to live in similar stacked spaces, older residential buildings also followed similar shapes and aesthetic pursuits, almost all of them looking the same.

The free will we seek should enable us to create different designs according to the different needs of different people with different lifestyles. As designers, we should feel challenged when designing due to the non-standard requirements of real users. The ultimate goal is to be free to exercise our own will while satisfying real users as designers.

Free will generally involves everyday actions that affect only a few people at most. An appropriate design should not be tailored to specific conditions and specific individuals, which makes the application of free will more difficult.

Designing a home brings with it the challenge of creating a ritual for the people who will live there. Your choices regarding the layout and orientation of the plan are the first steps toward a functional architectural design.

Free will should cause some pain.

It should make you sweat. Because true freedom is not escape, it requires responsibility.

If your home has a sea view, you can place the bathroom on the front side.

If you wish, you can create your own small garden in the bedroom and allow the other rooms to enjoy the city view without walls.

However, it is important to remember that these analogies must at least make sense to someone.

Another point to keep in mind is that because we have free will, we should not go to extremes in design.

We should create a third perspective or seek input from others on when to stop designing and when to take action to turn the design into reality.

Freely will, which has been much discussed recently, is not a blank check for a person’s behavior, but should be interpreted as creating third options when the options given are not sufficient for the design.

Your ability to create a third option in your life choices is true wealth and wholeness.

Because you should never have to choose between living and dying.

As we try to test the limits of our free will, we should seek other perspectives that can help us identify the real issues. We should not hold radical or fixed views in our relationships with others. We should not blindly criticize or praise.

Perhaps free will is not something we possess passively, but rather an active act of testing and adapting.

It is about creating something that did not exist before, by daring to dream.