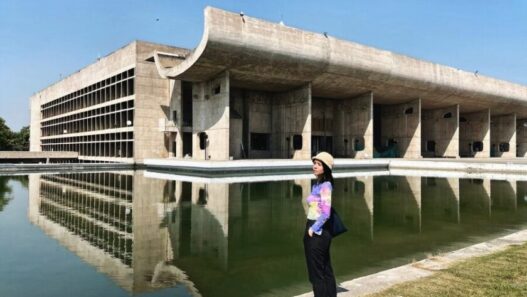

Chandigarh India Mid-Century Modernism

This city, standing like a concrete poem against the foothills of the Himalayas, is a startling declaration of a new India. It is not an organic growth but a complete architectural work, a symbol of post-colonial ambition cast in raw concrete and geometric order. Its significance lies in this boldness, which translated European modernist ideals into a context distinctly Indian—through light, climate, and social aspirations. Chandigarh represents the moment a nation chose its future form, turning urbanism into a national monument.

The Visionary Birth of a Planned City

Its origin stems from a profound loss, conceived to replace Lahore as the capital after partition. This idea aimed to physically manifest the optimism and rationality of a newborn state, transcending mere administrative concerns. It was not just urban planning, but an attempt to build a nation with bricks and mortar, to organize society through design. The starting point was a clean slate—a rare opportunity to construct a perfect city from scratch, making it both a profound opportunity and a great responsibility.

Ambition After Partition: Nehru’s “City of the Future”

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru envisioned this city as an escape from its colonial past and the chaos of historic cities. He called it the “city of the future,” symbolizing a progressive, scientific, and forward-looking India, free from the burden of traditions. This ambition was a deliberate political act that used architecture as a tool to forge a modern citizenship. The city’s very existence was a statement that India could harness the latest global ideas for its own renaissance and make urban form a catalyst for

Le Corbusier Takes the Helm: From Master Plan to Manifesto

When the original American plan failed, Nehru turned to a global icon of modernity. Le Corbusier arrived not merely as an architect, but as a prophet, imposing his Radiant City philosophy onto the plains of Punjab. His master plan was a grand, humanistic diagram—organizing functions with a sculptor’s sense of scale and a philosopher’s sense of order. This was his ultimate canvas, where the principles of sun, space, and greenery became a sweeping, lived manifesto for modern

The Role of Pierre Jeanneret, Maxwell Fry, and Jane Drew

While Le Corbusier provided the overarching vision, these architects translated it into the fabric of daily life. Designing the vast majority of the housing, schools, and markets, they balanced modernist rigor with a practical sensitivity to climate and culture. Their work infused the monumental plan with warmth through the use of local brick, innovative sunbreakers, and human-scale proportions. This collaboration ensured the city was not just a theoretical masterpiece but a livable home, grounding the grand vision in the details of everyday use.

“Sectors”: Organizing Urban Life into a Human-Scale Network

Each sector is an independent neighborhood, a village within the modern machine. This repeating grid creates a democratic urban fabric where no area holds privilege over another in its fundamental structure. The design fosters a sense of community by placing markets, schools, and green spaces within walking distance, making the vast city feel intimate. The sector system is Chandigarh’s genius—a repetitive yet humane module that transforms chaos into a legible, peaceful, and deeply ordered pattern of life.

Architectural Philosophy and Descriptive Characteristics

The belief is that buildings should serve not merely as shelters, but as instruments of social and spiritual progress. This philosophy translates into an architecture where every line carries meaning, possessing both a rational order and an intensely poetic quality. The resulting forms are monumental yet humane, creating spaces that feel both ancient and futuristic through the use of raw materials. They offer calm and orderly environments, intentionally contrasting with the chaos of the surrounding city.

Five Points of Architecture Redesigned for India

Pilotis, or slender columns, lift buildings off the Indian terrain, creating shaded public plazas beneath that accommodate community life. The liberated facade, freed from load-bearing walls, becomes a sculptural screen of sun breakers, a direct response to the harsh subcontinental light. The open plan adapts to fluid, multifunctional living, reflecting a culture less bound by rigid room definitions. Long horizontal window frames offer curated views of the landscape, while the rooftop garden compensates for lost ground,

Local Touch Brutalism: Concrete, Brick, and Stone

Ham concrete is not a cold industrial export product, but a warm, textured canvas that captures the interplay of sharp Indian sunlight and deep shadows. Local brick and roughly hewn stone, woven with a brutalist grammar, anchor these monumental forms within the region’s material memory. This synthesis creates a tactile architecture that feels both universal and distinctly of its place; its roughness invites touch and ages gracefully over time. The honesty of the material speaks of permanence and resilience—values deeply embedded in the local context.

Modular Man: Le Corbusier’s Proportional System

This system, based on the proportions of a standing figure, serves as a mathematical bridge between human scale and cosmic order. It governs everything from window dimensions to the layout of an entire city, creating an invisible harmony that the body intuitively perceives. The result is an architecture that feels inherently balanced and correct, where spaces are neither cramped nor overwhelming. By imposing a rhythm of grace and efficiency, it transforms construction into a kind of visual music grounded in human existence.

Climate-Sensitive Design: Sunshades, Pools, and Verandas

Architecture engages in an active dialogue with the sun through deeply carved brise-soleil that filter light and create ever-changing shadow patterns. Reflective pools and water channels are not merely decorative elements but also serve as passive cooling devices, their evaporation subtly balancing the microclimate. Broad, shaded verandas and overhangs act as transitions between interior and exterior, promoting airflow and offering spaces for repose. This is a performative design where form directly follows environmental function, creating comfort through intelligence rather than energy

Sculpture Form and Symbolic Geometry in Major Capitals

These buildings are designed as sculptures with expansive spatial layouts, their forms carrying the symbolic meaning of a newly independent nation. The parabolic curve of the roof evokes the yoke of an ox cart, linking modern governance with agricultural origins, while the monumental columns abstract the shape of banyan trees. Geometry becomes a language of power and aspiration through circles representing continuity and pyramids reaching toward the sky. These structures are not merely administrative centers but three-dimensional manifestos crafted to awaken civic pride and collective identity through their unforgettable presence

Permanent Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

This city stands out as a rare, complete example of a modernist utopia built from scratch after partition. Its legacy is not a frozen artifact but a living debate about the role of design in society. The city remains significant today because it continues to raise profound questions about order, community, and public beauty in a rapidly changing world. Its importance lies in the enduring power to inspire and provoke—a testament to the idea that the environment shapes human potential.

Living Heritage Site: Conservation Challenges and Achievements

Here, preservation does not mean encasing in a glass dome, but rather sustaining a functional organism. The challenge lies in balancing the conservation of the original concrete structure with the evolving needs of its residents. Successfully restoring significant buildings to their intended grandeur and public use is an achievement. Each rescued structure proves that Modernist heritage can both be preserved and inhabited, reaffirming the city’s status as a shared global legacy.

The Influence of Chandigarh on Indian Architecture and Urban Planning

By dismantling colonial and revivalist models, it introduced a new language to the subcontinent, characterized by exposed concrete, geometric forms, and open spaces. Its influence is evident in the work of subsequent generations of Indian architects, who embraced a rational and expressive approach to building. The city’s sector-based plan, prioritizing greenery and hierarchy, became a powerful template for regulating urban growth. This plan demonstrated that a distinct Indian modernity was possible—one that was forward-looking yet rooted in its own context and climate

Modernist Furniture and Crafts: The Story of the “Chandigarh Chair”

Born out of necessity, these pieces were an integral part of the architectural vision designed to furnish new public buildings. With its teak frame and cane seat, this iconic chair represents a beautiful synthesis of industrial design and traditional Indian craftsmanship. Its story is one of rediscovery, transforming from discarded government surplus into a global design icon. This journey highlights how functional objects can become cultural symbols and carry the narrative of a place far beyond its borders.

City of Today: Between Preservation and Progress

Chandigarh is currently in a dynamic tension; its original sectors stand alongside informal growth and contemporary development pressures. The core debate unfolds between the guardians of its architectural purity and the forces of demographic change and economic demand. This negotiation defines the city’s current character, which is a dialogue between a fixed past and a fluid future. The city’s true test is to evolve without erasing the foundational ideals that give it a unique form and spirit.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.