Architecture distributes opportunities for living because it distributes space, light, access and prestige. Every plan is a map of who is welcomed and who is controlled. Materials indicate value, thresholds control belonging, and distances determine the cost of daily life. When design ignores these realities, buildings become silent tools of inequality; when it embraces them, they become tools for civil repair.

Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership – Danish Architecture Center – Studio Gang

Context: The Importance of Architecture in Social Justice

The built environment transforms ideas into habits, and habits into systems. A bus stop without shade reduces patience; a clinic far from transport shortens life expectancy. Development plans, regulations and capital transform politics into walls and roads that will last for generations. Therefore, design is not neutral, and justice must be incorporated into plans.

Historical inequalities in the built environment

From neighbourhoods marked with red lines to motorways passing through black and impoverished areas, the space has been used to separate risk from privilege. Colonial grids invalidated indigenous geographies, erasing water knowledge and food routes. Company towns and property blocks controlled labour and visibility. These patterns still resonate in heat maps, asthma rates, school districts, and property wealth.

The connection between architecture, public policy and social outcomes

Policy determines the framework within which buildings function as elements that either promote public health or harm it. Incentives shape what gets built, where, and for whom; regulations define whose bodies a space will accommodate. Transport, schools, clinics, and housing are a single spatial system that either multiplies opportunities or increases exclusion. Architecture is the visible tip of this policy iceberg.

From exclusion to inclusivity: the shift in design paradigms

Design has shifted from accessibility based on compatibility to applications centred on equality. While expanding universal design norms, inclusive and trauma-focused design places the most affected individuals at the centre. Public interest and community-focused processes are redefining value as collective well-being by changing ownership. The aim is not a new style, but a new ethic measured by lived outcomes.

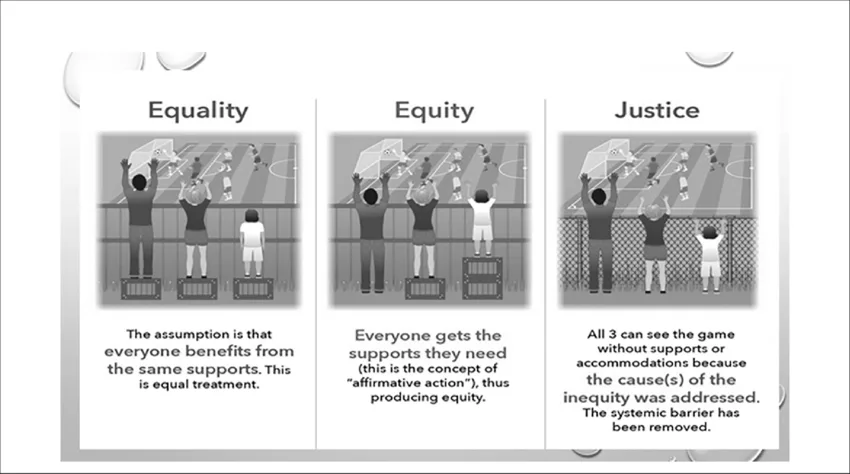

Terminology and definitions: equality, justice, community design

Equality is the fair distribution of resources and burdens from different starting points. Justice is the redress of historical harm and the redesign of the systems that produced it. Community design is a practice guided by local knowledge and treats residents not as stakeholders but as co-authors. When these terms come together, they position architecture not only as an aesthetic endeavour but as a moral responsibility.

Design Principles for Equitable Development

Equality-driven development treats space not as a private luxury but as a public contract. This approach questions who holds the power, who benefits from the plan, and who pays the price in the long term. The result is a design measured not only by aesthetics but also by outcomes in health, mobility, culture, and prosperity. The frameworks in this field formalise this change and help transform values into enduring standards.

Participatory and community-focused design processes

Participation is not a workshop; it is a redistribution of power where residents collectively make decisions and control the outcomes. Arnstein’s ladder highlights the difference between symbolic consultation and citizen power and serves as a useful test for any process that claims to listen. Design Justice principles go further, placing those most affected at the centre and prioritising community outcomes over designers’ intentions. These models are important because when authorship is shared, legitimacy, accountability and resilience increase.

Universal accessibility and inclusive environments

Accessibility is a fundamental civil right that guarantees entry, movement and use for people of different sizes, ages and abilities. While the ADA sets minimum scope and technical requirements, Universal Design sets a broader goal for environments that can be used by everyone without requiring special adaptation. The shift from legal compliance to inclusivity moves the question from “is it permitted?” to “does it provide dignity?” This is important because cities that are suitable for more people are more suitable for the future.

Environmental justice and resource allocation

Environmental justice advocates that no group should bear a disproportionate share of pollution or climate risks and that everyone should be meaningfully involved in the decision-making process. Evidence shows that exposure to heat and fine particulate matter is not equal across racial and income lines. This means that design resources such as shade, transport, flood safety and clean air should be allocated primarily to areas where harm is concentrated. Planning with this perspective transforms parks, trees, cooling and emission reductions from opportunities into tools for remediation. Equity in placement and performance is the difference between resilience for some and resilience for all.

Material, space and economic transparency in design

Transparency makes trust understandable. Material declarations such as EPD, HPD, and Declare labels reveal life cycle impacts and hazardous components, enabling teams to select healthier, lower-carbon formulations. Corporate disclosures, such as the JUST label, bring the same clarity to labour, equity and community practices that shape a project’s unseen footprint. Publishing these metrics and costs reframes design not as a black box, but as a public ledger of impacts.

Examples

Examples are important because they translate values into tangible places where people can engage with them. Each of the following examples demonstrates a different lever for equality: tenure, authorship, mobility, memory. Read these as evidence that cities can redistribute prestige on a large scale.

Affordable housing and mixed-income housing projects

Via Verde in the South Bronx redefines the concept of “affordable” as healthy urban living, transforming 222 mixed-ownership homes into daily entitlements by combining them with terraces, gardens and natural light. In Chile, Quinta Monroy secured a central plot of land for 100 families through a phased “half-house” approach, proving that residents could gradually complete and personalise their homes over time. Vienna’s city-wide system demonstrates the power of policy architecture: approximately 220,000 council flats and subsidised housing maintain a broad social mix and alleviate market pressures. Together, they show that affordability is not an end point, but a civil infrastructure comprising health, property and choice.

Community centres, public infrastructure and social centres

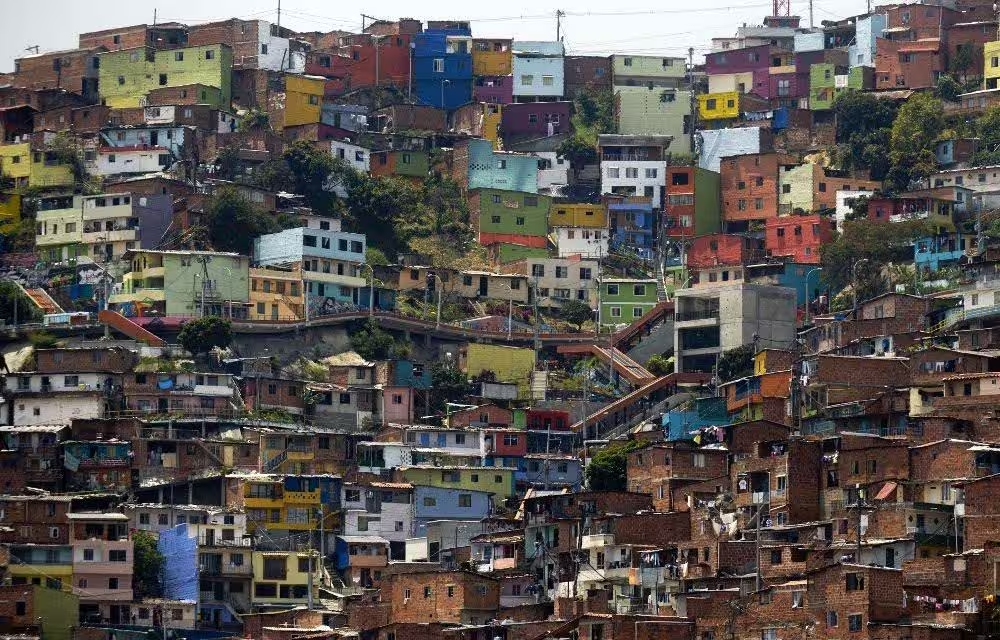

Medellín’s “social urbanism” approach linked library parks and the Metrocable to social infrastructure. Research has linked this period to a sharp decline in violent crime and expanded access. The lesson to be learned here is not about showmanship, but proximity: culture, education and mobility have been integrated into the hillside neighbourhoods as everyday services. Bogotá’s TransMilenio and ciclovía networks add a second model, where streets function as weekly public spaces and bus lanes redistribute time, cost, and access for working-class passengers. Centres that transport people and information are as vital to any justice agenda as housing.

Adaptive reuse and urban regeneration in underserved areas

The Granby Four Streets in Liverpool is a regeneration project led by residents. The community land trust and Assemble collective have restored terraced houses, provided training to neighbours, and gained cultural recognition that has helped the project gain momentum. In Chicago’s South Side, Theaster Gates’ Rebuild Foundation transformed vacant buildings into the Stony Island Arts Bank and a network of cultural assets, turning dereliction into shared archives and civic pride. These projects argue that reuse is not nostalgia, but repair; that it preserves value and keeps ownership in the hands of the community. Impact is measured by retained ownership, developed skills, and reclaimed streets.

Collaborative design projects in historically marginalised communities

Rural Studio’s long-running 20K House research in Alabama combines education with practice, building real homes for local residents while examining total cost of ownership. MASS Design’s Butaro Regional Hospital in Rwanda harmonises form, health and livelihoods by integrating infection control architecture with local labour and materials. Thailand’s Baan Mankong programme further expands collaborative design by channelling public funding to community groups for property, improvement, and settlement decisions across thousands of settlements. This collaboration is not a social welfare activity; it is an operating system that transforms design into a shared capacity.

Implementation Strategies for Architects and Designers

Equality is not a state of mind; it is a set of commitments you can verify. Incorporate these commitments into summaries, teams, contracts and evaluations so that the project does not revert to old habits. Below are compact steps that translate values into accountable practices, from the initial meeting to long-term management.

Integrating equality criteria into project summaries and delivery

Write your summary as a contract that includes not only the scope but also the outcomes. Set targets for accessibility, affordability and cultural fit using the AIA Framework’s Equitable Communities questions, then track these targets through design reviews and payment practices. Combine this with the Social Value Toolkit and post-occupancy evaluation to ensure that lived experiences inform future work. In the housing sector, link design to health by adopting Enterprise’s Health Action Plan and resident-focused criteria.

Creating inclusive teams and diversifying stakeholder voices

Inclusive outcomes require inclusive authorship. Starting with the AIA Equal Application Guidelines, define topics such as recruitment, pay equity, mentoring, and psychological safety not as privileges but as core activities. Extend transparency to the organisation itself with the JUST label, so that workforce, equality and community metrics become visible to customers and communities. Diverse teams and clear accountability improve insight, legitimacy and employee retention.

Advocacy, political participation and long-term community management

When policy and practice come together, the impact of design increases. Use Community Benefit Agreements to incorporate local employment, displacement prevention funds, and public space maintenance agreements into legislation. Support participatory budgeting to ensure capital decisions reflect the priorities of local residents, and support community land trusts to secure affordable housing beyond a single project. Advocacy safeguards the conditions necessary for your design to continue working.

Measuring results: social impact, resilience and lasting change

Measure what people actually gain. Combine post-occupancy evaluations to track social value indicators alongside energy and cost, as well as well-being, belonging and usability. In affordable housing, use Green Communities outcome tools to link design choices over time to residents’ health. Publish findings to help the project move beyond being a closed chapter and become a local reference point.