Architecture is both a public trust and a personal stance. Throughout history, the figure of the architect has changed according to the needs of society, but its fundamental claim has remained the same: to shape life with judgement, knowledge and care.

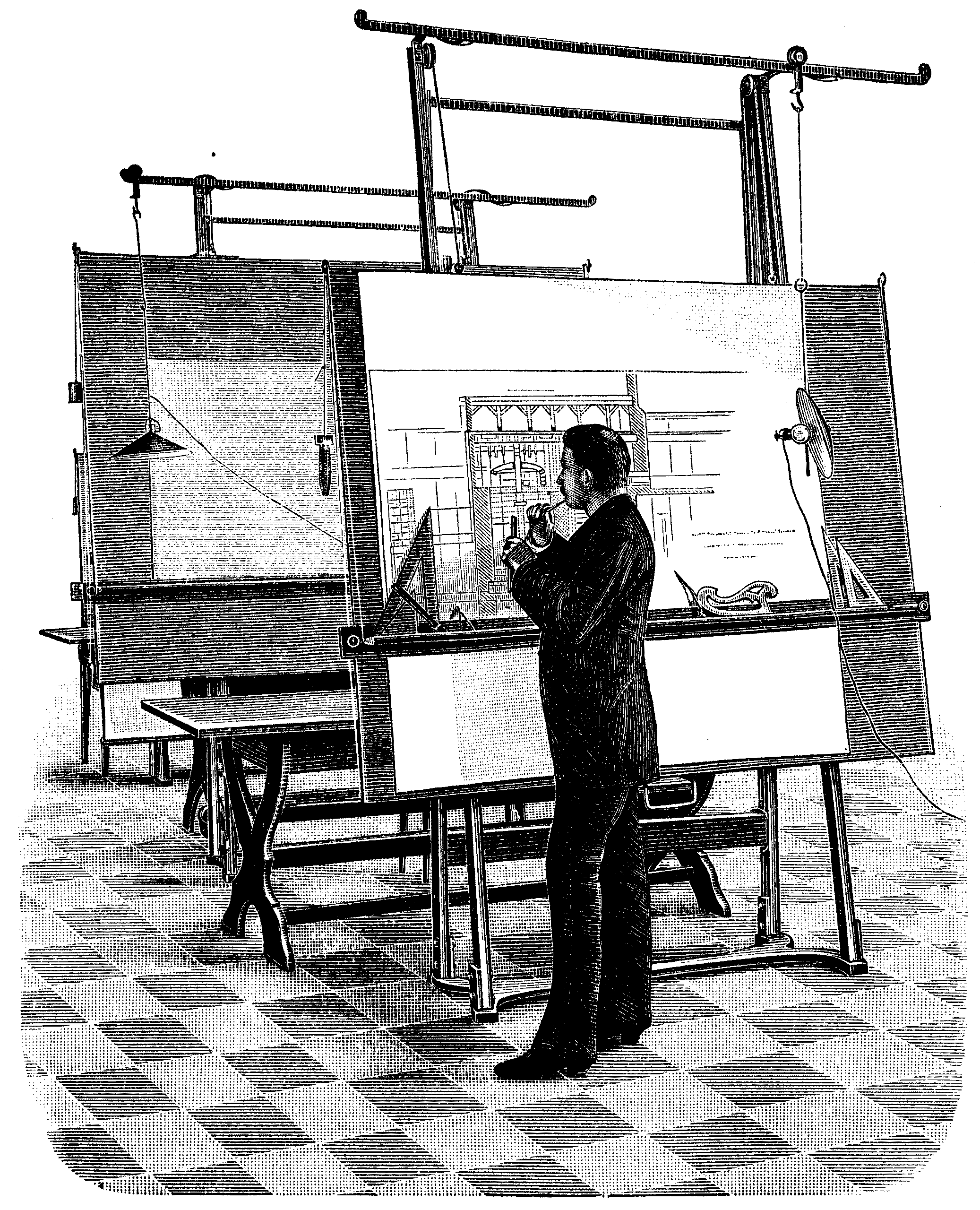

An architect working at a drawing board.

This wood engraving was published on 25 May 1893 in Norway’s leading engineering journal, Teknisk Ukeblad. This engraving illustrates an article about a new type of vertical drawing board launched by the J. M. Voith company in the city of Heidenheim a. d. Brenz (Southern Germany). The board measures 1800 x 1250 mm, has a total height of 2800 mm and weighs 220 kg.

To understand identity, one must examine traditions, laws and past practices together.

Identifying the Architect’s Identity

From builder to designer, from designer to architect

In ancient times, the architect was a knowledgeable craftsman who combined theory with craftsmanship. Vitruvius defined this role through education, reasoning, and the coordination of various skills. Humanism redefined the architect as an intellectual designer. Alberti argued that logic, proportion, and authorship were the elements that distinguished architectural work from simple construction. Modern professionalisation added elements of regulation and public accountability, transforming social prestige into a licensed responsibility. Today’s title rests on three foundations: technical mastery, cultural authorship, and official duty to the public.

The professional definitions and cultural expectations of an architect

Today’s regulations define architects as professionals responsible for safeguarding health, safety, and well-being through competence, integrity, and clear client services. Registration frameworks and verification systems translate this commitment into education, experience, and ethical standards, aligning personal practice with public oversight. Culture often expects more: the guardian of urban meaning, a voice on environmental and social issues, and the champion of quality. The result is a role measured not only by beautiful buildings but also by accountable judgements within the framework of the law.

The architect’s inner world: mindset, motivation, profession

Architectural thought, drawing, construction and perception live in the body and mind, becoming a single cycle of attention.

This work requires discipline to transform empathy, patience with constraints, and intuition into a testable form. Many architects experience this profession as a long apprenticeship of vision, where the hand teaches the eye and the eye teaches the plan. The profession emerges when this internal training meets an external service ethic.

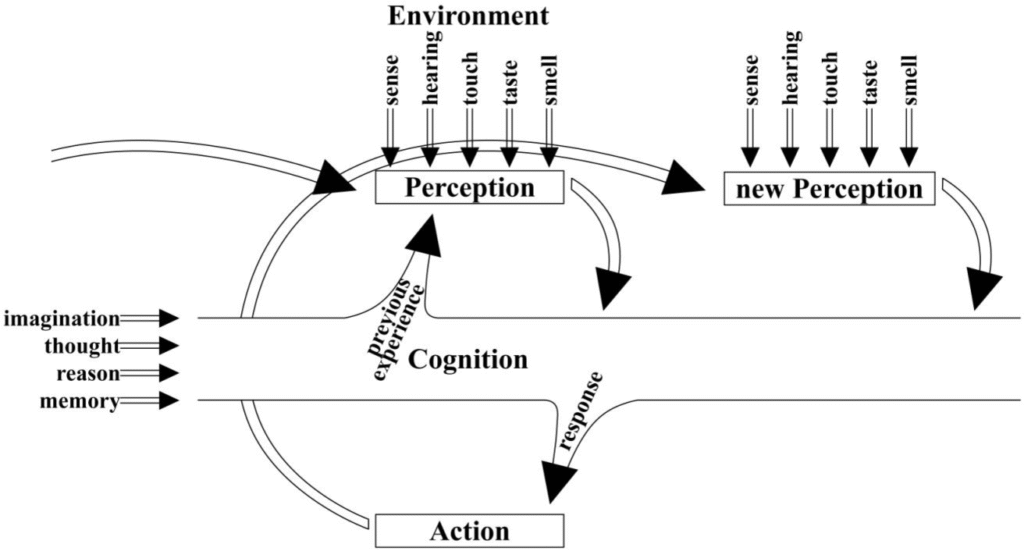

Detailed Explanation of the Diagram

This diagram visualises the perception, cognition and action cycle — a model showing how people interact with their environment, how they process information and how they develop new understandings through experience.

1. Environment

The cycle begins with the environment providing stimuli through the five senses:

- vision

- hearing

- touch

- tat

- koku

These sensory inputs are constantly fed into our perception system.

2. Perception

Perception is where raw sensory data is first received and interpreted. It transforms environmental signals into a mental representation — how we see or feel reality.

From perception:

- Knowledge flows upwards (for interpretation and reasoning).

- It also creates actions based on instant responses.

- This is influenced by previous experiences that alter how we interpret new inputs (feedback loop).

3. Cognition

Cognition involves mental processes that operate on perceived data. It includes the following:

- Imagination

- Thought

- Reason

- Memory

These elements enrich perception with context, enabling the mind to:

- Comparing current feelings with past experiences

- Judgements and decisions

- Creating a response

This response then proceeds to the Action stage.

4. Action

Action is the behavioural or physical output produced by cognition.

This can be a motor movement, verbal expression, or even an internal decision.

When the action occurs, it changes the environment and feeds new sensory information back into perception, restarting the cycle.

5. Feedback and New Perception

After an action environment changes, the senses receive new stimuli and create a new perception. This new perception flows back into cognition under the influence of the following:

- Past experiences

- Memory and reasoning

- The effects of recent actions

This continuous cycle ensures that each new perception is shaped by previous learning and constantly updates our understanding of the world.

Summary of the Flow

Environment → Perception → Cognition → Action → Environment (repeat)

Within this cycle:

- Perception interprets the input.

- Cognition processes and gives meaning.

- Action applies this meaning in the world.

- The result of the action reshapes the new perception guided by memory and experience.

How do perception and self-perception shape the architect’s role?

The architects of society, from master builders to renowned designers and public professionals, frame what customers and communities want us to do.

Architects, writers, mediators or guardians of the public sphere act according to the roles they see themselves in, and self-perception completes this cycle. Ethical rules and historical narratives become mirrors that guide behaviour and ambition, reinforcing responsibility for the exhibition. The healthiest identity is one that balances authorship with service.

The Architect’s Relationship with Space and Being

Architecture as a way of existing in the world

Architecture is not merely shelter; it is a way of situating human life within the world order. For this reason, Heidegger relates the structure to dwelling as a fundamental form of existence. Good housing is to maintain a living dialogue between Earth and Sky, the mortal and the sacred, lending consistency to spaces. This view shifts architecture from object construction to an emphasis on existence and context. This task is a cultural and ethical one before it is a technical one.

The phenomenology of experience and space on a human scale

People perceive space with their entire bodies; therefore, architecture must appeal not only to the sense of sight but also to the senses of touch, hearing, weight, light, and temperature. Pallasmaa’s critique of “eye-centrism” reminds us that rooms are successful when they are based on the senses and memory. Zumthor refers to this characteristic as atmosphere, the felt character that affects us before analysis. Gehl demonstrates that streets and squares that invite life in cities are subject to the same human scale.

Pallasmaa, J. (2005) The Eyes Of The Skin

Importance, the environment and the architect’s responsibility

Materials carry cultural meaning and carbon; selecting them is both a poetic judgement and a climate action. The AIA Code of Ethics frames this as a professional duty, from energy and water targets to material health and ecosystem impact.

RIBA’s Sustainable Outcomes and Architecture 2030 targets make this task measurable across operational and embodied emissions. Therefore, responsible material use is the link between craftsmanship, regulation and a liveable future.

The architect who acts as a mediator between ideas, spaces and residents

Good architecture transforms ideas into forms that reveal the spirit of a place and serve the people who live there. Norberg-Schulz refers to the emergence of this genius loci as the existential purpose of the structure. While Zumthor achieves this through atmospheres that connect the building to emotion, Frampton’s critical regionalism advocates for considering climate, topography, and culture over abstractions independent of place. Mediation is not compromise; it is the art of making meaning shareable in built form.

The Architect’s Ethical and Philosophical Foundations

Design ethics: being an architect means more than just form

Architecture makes a commitment to the public to safeguard health, safety, welfare and integrity; this makes ethics as much a real design constraint as structure or budget. Professional rules translate this commitment into canons and enforceable regulations, ranging from honesty towards clients to avoiding conflicts that would compromise judgement.

International agreements expand this framework, requiring architects to work in accordance with the laws and ethical standards of the places they build. In this sense, ethics is not an appendage to form, but rather the atmosphere that allows form to gain meaning.

Philosophical roots: meaning in architecture, housing and human development

Heidegger, linking architecture to settlement, argues that architecture brings together the earth and the sky, the mortal and the sacred, in places where life can take root. This transforms architecture from being about objects to being about maintaining a world with consistency. Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia envisages development in a life shaped by virtue and the common civic order, inviting architecture to support not merely living, but living well. These roots transform meaning from a decorative addition into a practical necessity.

Social and environmental responsibility in the architect’s way of being

The climate crisis is making material selection and energy use measurable and verifiable ethical decisions. Goals such as RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge and Architecture 2030’s concrete carbon actions are translating ideals into outcomes in terms of both operations and materials.

UIA’s global declarations incorporate the professional duty of protecting the planet by calling for carbon-neutral planning, prioritising renovation, and responsibility at the city level. A reliable application combines poetry with performance and leaves a lighter footprint.

Challenges related to the originality, integrity and commodification of architecture

In a culture dominated by images, architecture can drift into a “rubbish heap” where composition is replaced by accumulation and the meaning of spectacle is eroded. Debord’s critique of spectacle warns that if judgement succumbs to advertising, commodification can transform the environment into a product and citizens into consumers. Rules requiring honesty and the avoidance of misrepresentation remind architects of integrity, which serves as a point of reference against this deviation. Original works resist by adapting form to reality, to the space, and to the people who inhabit it.

The Path to Becoming and Remaining an Architect

Education, apprenticeship and the shaping of the architect’s identity

An architect’s identity is shaped by a three-part structure comprising education, supervised experience and examination, linking creativity with public service. A degree accredited by the NAAB formalises broad competence and demonstrates readiness for health, safety and welfare services. Apprenticeship undertaken through the Architectural Experience Programme deepens this promise by logging hours in core practice areas under the guidance of licensed mentors. Together, they transform talent into responsible judgement.

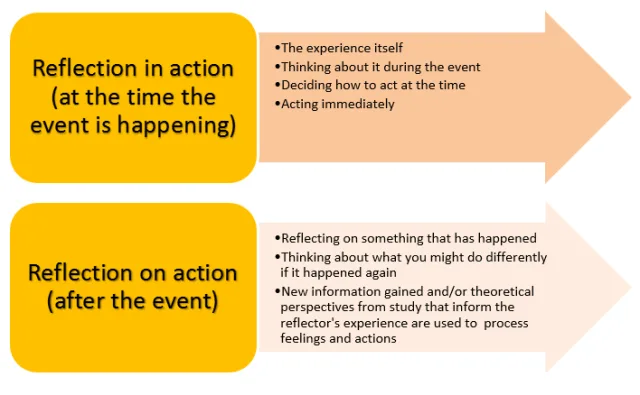

Daily practice: habits, reflection and the constant art of being

Craftsmanship persists through the daily repetition of the cycle of observing, producing, and naming what is learned. Therefore, Schön’s “reflection-in-action” approach remains a valid method in design. A studio environment filled with notes, models, and critiques sharpens perception and transforms uncertainty into insight. The formal requirements for continuous development reinforce this rhythm and demand that architects renew their competence annually according to open public standards. When routine becomes the laboratory of attention, practice matures.

Coping with professional pressures: commercial, regulatory, reputational

Projects progress through phased commitments where ideas meet contracts, risks and legal obligations, and the architect must ensure consistency between them. The RIBA Work Plan clarifies these stages from strategic briefing to handover, aligning roles, information and decisions.

Pressure stems from cost, time, responsibility and image, but the measure of the role is consistency in translating intentions into accountable outcomes. Clarity of stage and responsibility protects both imagination and public opinion.

Maintaining creative, ethical and existential harmony over time

Harmony acts as a compass, uniting shared responsibilities such as personal voice in climate action, equality, and long-term resilience. The AIA Design Excellence Framework distils these into ten principles that test the meaning of every project against its impacts. Embracing this framework means saying yes to projects that empower places and people, and no to those that weaken them. Sustainable practice is the art of renewing our purpose while honouring the promises we make to the world we build.

Four Results:

Architects’ responsibility to protect public health, safety and well-being also encompasses the challenges of mitigating increasing climate extremes and social inequality. Architects everywhere must recognise that our profession and every project can contribute to finding creative and positive solutions to the most pressing issues of our time by harnessing the power of design. In 2019, the AIA adopted four outcomes as part of its Climate Action Plan. These are:

- Zero carbon: Making all new buildings and refurbishments carbon neutral will protect people, ecosystems and assets by reducing the devastating effects of climate change caused by the construction sector. When assessing a building’s total carbon impact, both operational and structural carbon must be taken into account.

- Equality: In the built environment, it promotes the inclusion and access of people who are underrepresented and who fight for justice. Centring equality in practice creates safe and welcoming environments that address historical injustices, resulting in a better environment for everyone.

- Resilient: Preparing buildings for a future characterised by increasingly severe climate challenges enables occupants to weather extreme events, maintain operational capabilities, and recover swiftly. A resilient project addresses social, economic, and environmental issues.

- Healthy: Architects are responsible for protecting the health, safety and wellbeing of the public. This encompasses not only the occupants of buildings, but also a wider user community: this includes the community in which the building is located, those who construct and maintain the building, those who source, produce and transport the materials, and future generations.

https://www.aia.org/design-excellence/aia-framework-for-design-excellence/introduction