Architectural curricula have historically oscillated between formal composition and programmatic problem solving. The classical École des Beaux-Arts tradition (France, 17th-19th centuries) emphasized large compositions, ornamentation and perspective. In this model, students learn classical layouts and highly detailed visualization techniques, aiming for beauty and harmony.

In contrast, the Bauhaus (Germany) of the early 20th century clearly reacted to this, offering a preliminary course in materials, color and form, but always with “function, materiality and efficiency” in mind. Bauhaus students quickly moved into ateliers and architectural studios, pursuing the ideals of simplicity and “form follows function”.

This legacy lives on: Many US schools adopted Beaux-Arts-style studios (e.g. MIT’s École-inspired competitions) but later integrated Bauhaus methods. As one review notes, the basic studio pedagogy at Beaux-Arts was problem-based and “learning by doing”, with student projects regularly critiqued – a model that continues to underpin modern design studios.

In practice, different regions blend these traditions. Scandinavian schools (e.g. Scandinavia) emphasize social and environmental functions. “In Sweden, very clearly form follows function”, Swedish designers say, reflecting a curriculum that emphasizes user needs, sustainability and social context.

In Japan, too, education emphasizes craft, context and a philosophical “Zen” minimalism: as one architect put it, Japanese design often involves “stripping away necessity” to reveal essential form.

Education in the US today is mixed: some studios prioritize formal innovation (especially in competitions), while others emphasize behavioral mapping, programming and social impact. Pioneers like Gropius at Harvard and Aravena’s practice now emphasize architecture as a “social service” and teach students to map human needs and site conditions before drawing facades.

The studio culture reinforces these priorities. In a typical design studio, students first collect data about the program and site (social surveys, climate, circulation), then iteratively prototype floor plans and massing models. Critique sessions challenge them to improve not only the surface appearance, but also user flows and structural logic. Some curricula formally require programming exercises or community projects (e.g. “community design” studios involving real users). This iterative, human-centered approach is strongest in regions influenced by Bauhaus or welfare state ideals (Scandinavian countries, parts of Japan), while schools influenced by Beaux-Arts may still lead with formal composition.

Regional Education Differences

| Tradition / Region | Pedagogical Focus | Curriculum Features | Sample Quote/Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beaux-Arts (France/USA) | Form-oriented composition | Workshop competitions, classical layouts, perspective drawing; criticism of finished aesthetic works. | “Richness, beauty, harmony…” – 19th century US schools modeled on École standards. |

| Bauhaus (Germany) | Integration of function and craft | Preliminary workshops (material, color), emphasis on construction and program; “form follows function” philosophy. | “Focus on function, relevance and efficiency…”. |

| Scandinavia (Nordic) | Social, functional design | Studio-based, project/problem-oriented; sustainability and social welfare integrated; strong site/context analysis. | “In Sweden… form follows function”; mixed-income housing ensures high user satisfaction. |

| Japan | Contextual minimalism | Master-apprentice mentoring, attention to craftsmanship, Zen-influenced simplicity; integration of tradition and technology. | “The Zen idea of letting go of necessities”; for example, the Sfera House of Culture (Kyoto) blends form and context. |

| United States | Hybrid/competitive design | Different approaches: Beaux-Arts heritage (class critiques, rendering) and modern pragmatism (e.g. DesignBuild programs); increasing emphasis on social responsibility. | 1950s public housing (Pruitt-Igoe) was designed as a modernist “living machine” but failed due to neglect of social context; current pedagogy disputes this history. |

Education shapes priorities: Bauhaus or social welfare ethos-influenced curricula train students to start from the user/program, while more classical or style-oriented programs may reward formal exploration first. However, most modern schools now aim to strike a balance, using studio-based prototyping and continuous feedback to ensure “form-follows-function” thinking.

Public/Civil Architecture: Functional Priorities versus Aesthetic Outcomes

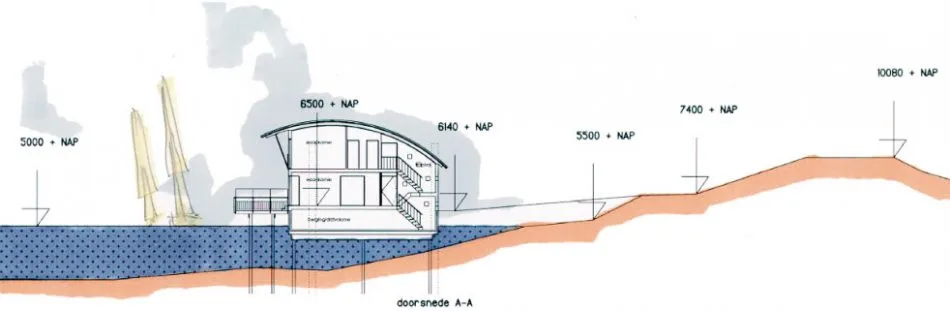

In practice, regional priorities (affordability, community, climate) strongly drive spatial organization before shaping. In the Netherlands, for example, social housing design integrates sustainability and community needs. Dutch projects often include mixed-income units, common areas and climate-adaptive features. A famous example is Maasbommel‘s amphibious houses, designed to float above flood waters (with the addition of a concrete pontoon foundation and flexible utilities).

This function-first approach (flood resistance) has even won awards and resulted in very high resident satisfaction – residents chose these houses for their “flood resistance”. Overall, the Netherlands consistently ranks top in the EU for tenant satisfaction thanks to integrated programming and quality of life in housing projects.

However, where façade/iconic design is prioritized, buildings can suffer. Contemporary architecture critics note that many projects emphasize a striking façade – “dramatic and visually striking” – while treating secondary facades and roofs as an afterthought. This creates “visual and functional gaps” in the urban fabric. Such facade-oriented design often leads to inefficiency or user dissatisfaction: internal layouts can be compromised, maintenance costs increase and community integration suffers.

This has been a factor in some notorious failures in the 20th century. US projects like Pruitt-Igoe (St. Louis) were conceived as modernist high-rise icons, but their uniform, isolated form ignored social program complexity. Within two decades, these towers were demolished amidst disrepair and social decline. These cautionary results underscore that neglecting user needs and context (in favor of a strong visual statement) can ruin a project.

In contrast, function-first housing tends to create more resilient and adaptable environments. Alejandro Aravena’s Quinta Monroy in Chile is an example of this.

Faced with a limited budget and a challenging terrain, Aravena’s firm provided each family with only “half of a good house”, focusing on the most complex common elements: walls, bathrooms, kitchens and structure. The remaining space was left for families to gradually fill in. This programmatic strategy – essentially sharing the “hard half” of construction – optimized land use and community (a central courtyard for 20 families) and empowered residents to expand organically. The result was affordable housing that residents could adapt to over time, a major achievement in a country where phased and participatory housing is valued.

Such real-world comparisons show that prioritizing functional programming (affordability modules, shared facilities, climate adaptation) often leads to better long-term outcomes, whereas prioritizing form or specific facades often leads to spatial inefficiencies.

Regional Social Housing Projects

| Region / Project | Priorities and Restrictions | Functional Design Feature | Result / Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands (Maasbommel) | Flood-prone site; resilience target | Floating/amphibian foundations, flexible service connections | The first test in 2011 was successful (houses were floated); residents reported high satisfaction; the project won Dutch adaptation awards. |

| Netherlands (General) | Social integration, sustainability | Mixed tenant blocks, shared amenities, green building systems | Among the highest EU satisfaction ratings; emphasis on light, air and community in programming. |

| Chile (Quinta Monroy) | Very low budget; need to prevent proliferation | “Half house” approach: kitchen, bathroom, structure (50% completed) provided in common block | Homes can be expanded by residents; density increases without extra subsidies; model praised for adaptability. |

| United States (Pruitt-Igoe) | Post-war housing shortage, modernist vision | Uniform high-rise blocks with minimal common areas | Social isolation and maintenance issues; demolished after ~20 years. Example of iconic form ignoring real user needs. |

Digital Tools and Parametric Design: The Impact of Technology on Form-Function Balance

The rise of computational tools has reshaped the design process, sometimes shifting the emphasis between program and form. Software like Rhino+Grasshopper, BIM platforms (Revit, ArchiCAD) and AI-driven generators allow architects to embed performance criteria into geometry or freely shape complex forms. Advocates note that parametric tools can actually improve programmatic design: for example, they allow for “real-time responsiveness” and space planning based on coded relationships. Research explains that “parametric tools are effective in space optimization”, enabling architects to overlay daylight, circulation and other data into a model so that layouts adapt to user needs. In practice, firms often use these tools for performance-driven design (for example, algorithmically optimized facades for solar gain or adaptive floor plans that respond to occupancy flows).

However, there is a well-known risk: the ease of creating eye-catching forms can encourage designers to reverse the usual order, starting with a showy form but then forcing function on it. Recent analysis has revealed that parametric ‘digitization’ has spawned an international style of bold forms that are often out of sync with the local context. While quantitative, code-friendly parameters (geometry, materials, environmental data) can be easily modeled, intangibles – cultural, historical or social factors – are difficult to code and often ignored. In fact, designers can produce sculptures on the computer without a deep understanding of how people will use them or live in them.

Both in education and in practice, this tension often arises in studios and competitions: advanced students can quickly iterate formal variants in software, but neglect initial program diagrams or user studies. It is possible to use the tools in a balanced way – indeed, parametrics are excellent when used to model functional requirements – but it requires discipline.

As noted, when used correctly, these tools lead to adaptive layouts: “By embedding programmatic requirements… architects can create layouts that adapt to changing conditions or user behavior”. In other words, the technology itself is neutral; success depends on starting from clearly defined functional goals. When form-building precedes a rigorous context analysis, projects risk the classic sculpture-as-a-service pitfalls, leading to post-use issues and high retrofit costs.

Key Tensions with Digital Form Making:

- Speed vs Understanding: Fast form creation can get in the way of careful field/program work. Students, in particular, may be tempted by curves generated on the fly, without paying enough attention to customer/user needs.

- Lack of Contextual Data: Tools can deal well with quantifiable data (sun angles, metrics), but “invisible” data (community rituals, local heritage) is more difficult to incorporate into the design.

- Performativity and Spectacle: Seductive visual outputs can further emphasize the “iconic facade” mentality. Observers warn that such designs can become aesthetically fragmented if secondary facades and user flow are not similarly considered.

Digital/parametric tools can both support and challenge function-first design. In strong programs, students learn to use them as performance modeling engines; in weak setups, the tools make it possible to pursue form without accountability. The result can be seen in practice: some buildings born from parametric experiments perform excellently (if driven by simulation goals), while others become textbooks on function failures rather than form. The oft-cited antidote is process: integrating digital form creation with iterative prototyping, site analysis and post-use feedback. In the end, successful architecture, whether analog or digital, returns to its users – a lesson that resonates in pedagogy and practice.