If you walk into a building and feel confused after taking just three steps, you’ve encountered shaky screens, multiplying directional signs, a lobby trying to be a gallery, café, and technology demo all at once, and excessive design. This is a reflex to add one more feature, one final touch, one more “wow” factor, even though the problem has already been solved. In architecture, this manifests as systems that require a guide to breathe, facades chasing spectacle over sunlight, and spaces that unintentionally tire people. The irony is that the more a building tries to do, the less space it leaves for you. Cognitive and environmental research tells us that when environments overload the senses, attention and decision-making abilities suffer; when the air is polluted or poorly managed, thinking abilities also suffer.

Excessive design is rarely malicious. It stems from good intentions, care, ambition, and perfectionism that go beyond usefulness. In product and project management, this deviation has a name: gold plating and feature creep. This pattern is the same across all industries: adding extra features to impress or protect against criticism tends to reduce clarity and usability. Architecture is no exception. When buildings are filled with unnecessary features, they become harder to operate, more costly to maintain, and perform worse in terms of energy and comfort than promised in the drawings. This “performance gap” has been documented for years and increases when complexity exceeds the capacity of those responsible for operating the space.

The health section is more sincere, though not as dramatic as the warning labels. An overly designed environment distracts us with constant micro-decisions and visual noise; it causes the air to become stale and controls to be misadjusted; it uses more materials than necessary and leads to unnecessary carbon emissions into the air we all breathe. The antidote is not simply belt-tightening. It is a human constraint: designing systems to the right scale, designing them for the people who will actually clean and operate them, and allowing materials, light, and air to do their work quietly. When we do this, cognitive functions improve, energy performance aligns with design intent, and buildings feel like living spaces again.

Understanding the Concept of Excessive Design

Simply put, overdesign is solving a problem more than is necessary. In projects, this usually manifests as features added beyond the scope of the brief or the user’s actual needs; project managers call this “gold plating.” It differs from careful refinement; it is late-stage expansion that dilutes the original value proposition and makes the result difficult to use. In digital and product design, this is called “feature creep”; it’s the pressure to add more to keep up with competitors or satisfy every stakeholder. When translated to a building, these excesses become maintenance headaches, training burdens, or comfort losses.

It’s not just about ergonomics or financial considerations; cultural and environmental issues are also at play. Complex buildings often fail to meet their energy targets during use; this is known as the “performance gap.” This translates to higher bills and higher emissions than the model predicted, precisely at a time when the sector is striving to achieve net carbon targets for both operations and materials. If we reinforce systems and structures “just in case,” we also increase carbon emissions from concrete, steel, glass, and cladding. RIBA and LETI’s advice on this matter is clear: Meet the need with less and measure what you contribute to the world.

What is Excessive Design in Architecture?

Imagine a school that has installed a complex facade shading system, electrochromic glass, automatic blinds, and a dense network of sensors, but does not offer teachers a simple way to reduce glare on exam days. Consider an office that uses three different ventilation systems, each perfect on paper, but where insufficient maintenance is performed to provide clean air to where people sit. Overdesign is not about a single technology being “bad”; it’s about solutions being piled on top of each other until the whole becomes fragile. Research on real buildings shows how easily sophisticated designs can deviate from real-world application if usage patterns, controls, and handover procedures aren’t grounded in reality. This gap between simulated and lived-in buildings is where occupants pay the price, both cognitively and financially.

There is also a sensory aspect. Neuroscience shows that when many stimuli compete with each other in our field of vision, they suppress each other in the brain; attention has a limited bandwidth. In cluttered or overly marked areas, people simply expend more effort to filter the environment. Multiply that effort over a day, and fatigue becomes real. Architecture can reduce this burden by calmly organizing light, edges, and cues, or it can increase it with constant stimuli.

The Origins and Psychological Factors of Excessive Design

Overdesign rarely starts as excess; it starts with care. A team wants to make something perfect and keeps improving it. However, there is a slippery slope where improvement turns into anxiety management: if we add another feature, function, or layer, perhaps no one will criticize us. Behavioral science has a name for a similar trap: the sunk cost effect. After time and money have been invested, the urge to continue rather than simplify arises, even if simplification would better serve the goal. Perfectionism in education and creative fields is praised until people burn out; the same mindset can also destroy projects.

In product and user experience applications, this situation manifests as adding “just one more” feature to meet imagined expectations, and NN/g points out that this often negatively impacts usability. PMI warns against “gold plating” in projects, because extra features added without a clear user need lead to program delays, budget overruns, and complexity in later stages. Architecture translates these lessons into steel, glass, and controls; costs become heavier and mistakes more permanent.

The Fine Line Between Subtlety and Excess

There is a difference between iteration that makes a building more functional and iteration that only makes it more complex. One way to stay on the right track is to treat the simulation not as a reward, but as a living hypothesis. CIBSE TM54 is very clear on this: estimate operational energy by paying attention to actual operating hours, possible occupancy rates, and controls, then design so that not only experts but also ordinary users can access the modeling results. A smooth handover is equally important. The BSRIA Soft Landings approach emerged because post-use reality often deviates from design assumptions; closing this gap requires not more gadgets, but sustained care and clear user interfaces.

On the human side, you can feel this limit when a space invites you to focus on working, resting, or playing without constantly demanding your interpretation. When choice becomes noise, the decision-making process breaks down. Iyengar and Lepper’s classic “jam study” highlighted this point beyond architecture: more options can lead to worse choices and less satisfaction. Design can preserve attention by making options clearer and fewer at the most critical moments.

Excessive Design as a Cultural Manifestation

Cities are filled with buildings trying to speak louder than the street. The pursuit of spectacle is nothing new; critics like Guy Debord argued decades ago that modern life confuses appearance with being, trading depth for spectacle. In architecture, this allure takes physical form. The risk is not merely aesthetic; chasing image can distance us from durable types, functional details, and spaces that are responsive to climate and culture. Aldo Rossi’s argument about collective memory provides a useful counterbalance here: cities embody long-term knowledge in their forms, and good architecture listens to this memory rather than drowning it in novelty.

This cultural pressure to impress can also lead to material and carbon budgets being unnecessarily inflated. Current climate frameworks are attempting to bring culture back to adequacy. RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge sets phased targets for both operational and embodied carbon; LETI’s Embodied Carbon Handbook provides designers with concrete strategies and targets. Achieving these targets is about restraint, reuse, and clarity, not decorative heroics; these qualities also make spaces more liveable.

Examples from Daily Projects

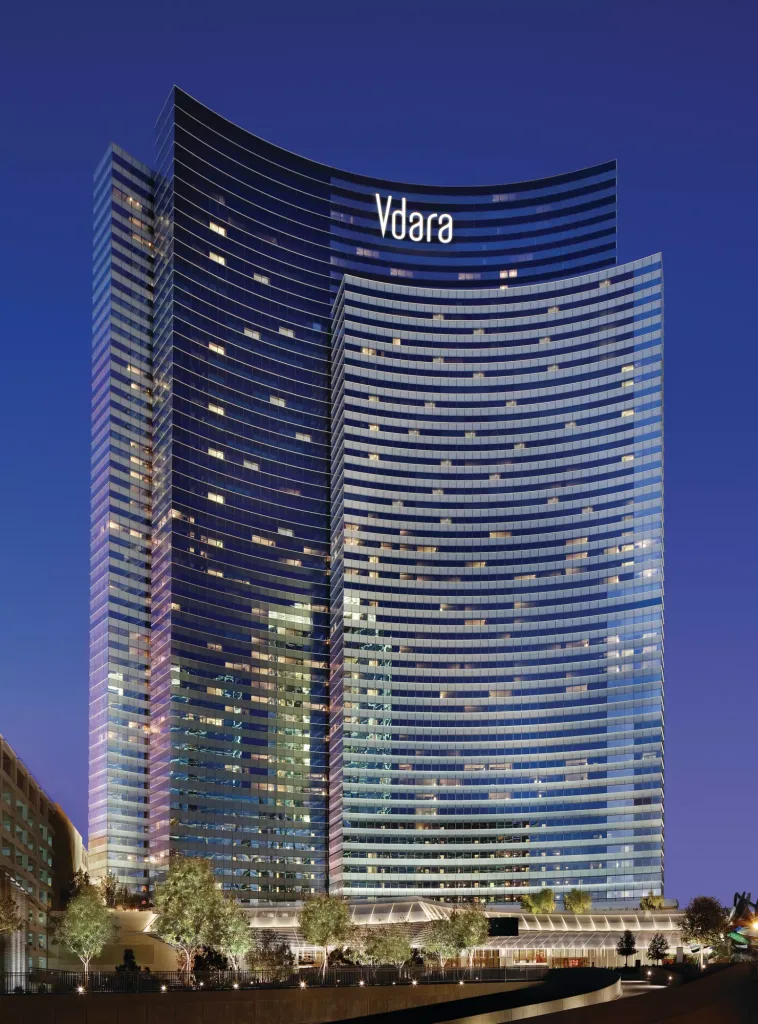

Sometimes excessive design literally burns. The concave, glassy geometries of the Vdara Hotel in Las Vegas and 20 Fenchurch Street in London concentrated sunlight into scorching hot spots at ground level. This dramatically reminded us that the pursuit of striking design can clash with the laws of physics and public comfort. In both cases, journalists documented the problem as it unfolded: melted plastics and burns in Vegas; softened car bodies and a scene resembling fried eggs on the pavement in London. None of this was intentional; they were unintended consequences of an official idea that overreached the microclimate.

The more common issue is silent failures. A school equipped with state-of-the-art control strategies that no one has time to learn. A perfectly designed residential block that consumes significantly more energy because its usage patterns, programs, or measurements are not understood. Evidence of this “performance gap” in the UK is extensive and has led to the creation of guidelines such as TM54 and Soft Landings to ensure solutions are proportionate and understandable for users. When designers focus on real-world operation and provide building occupants with simple, reliable control options, the air becomes cleaner, energy use aligns with purpose, and the building feels like a place that supports attention rather than a machine demanding it.

Personal and Collective Memory in Design

Every project carries two memories. The first is personal: the client’s story, the designer’s education, the team’s pride. The second is collective: the city’s characteristics, the region’s climate, people’s rituals of coming together, meeting, cooking, mourning, and playing. Excessive design stifles collective memories by inflating personal ones. When we design at the right scale, we make room for both. Rossi’s “city of memory” is a good guide in this regard: use enduring types and works as reference points. Phenomenological writers like Norberg-Schulz remind us that spaces have a spirit beyond their functions; spaces exist within a network of terrain, light, air, materials, and repeated human actions.

Designing with collective memory often results in fewer and better moves: truly shadow-casting deep projections, staircases that become social focal points, breathable courtyards. Additionally, because it respects what already exists and achieves more with less, carbon emissions are also lower. Contemporary goals, from RIBA’s concrete carbon thresholds to LETI’s clear rules on building less and lighter, give this respect concrete form. Beneath the numbers lies a human idea: a building that remembers its place and whom it serves does not need to shout. It will be healthy because it is simple in the right places.

When Creativity Becomes a Burden

In many projects, there comes a moment when dedication turns into pressure. You are no longer exploring; you are trying to silence the voice in your head. In psychology, this shift is seen as obsessive passion rather than harmonious passion: the work takes over you, not the other way around. Research across different professions shows that obsessive passion is associated with conflict, tension, and burnout, while harmonious passion supports satisfaction and better performance. In practice, this means that the same “love of design” can either give a team resilience or drag it into sleepless cycles that weaken its judgment.

Under this pressure, unfinished tasks gain power. Our brain tends to keep unfinished tasks alive; this is sometimes called the Zeigarnik effect. This feeling is not mystical; it is a tension that wants to be resolved. This tension can be useful when it pushes you to take action, but it can also trap you—even if it won’t lead to improvement, it might cause you to reopen your drawings in the middle of the night thinking, “It’s almost done.” Laboratory and field studies show that this effect is real but context-dependent. This is important in practice: use this effect to get started, not to get stuck in a loop.

Fear of Incompleteness

Perfection is often a mask for anxiety. When a detail feels unresolved, your mind won’t let it go, and this discomfort can ruin your entire program. The Zeigarnik model explains part of this appeal: unfinished tasks create constant cognitive tension, so even a brief “first glance” at a problem can make it easier to return and finish it later. In a studio, this is permission to make early sketches, establish a position, and relieve mental pressure; so you can choose your next move instead of chasing every possible one.

The trap is to confuse this tension with reality. Studies re-examining the Zeigarnik effect show that it is not a universal law; motivation, type of interruption, and context alter the results. Consider the phrase “I can’t stop thinking about it” as a signal, not a decision. Take structured breaks, write down the rest, and move the task to a specific decision point. The goal is to transform mental noise into planned action before the project enters an endless loop.

Architects and the Legend of Perfection

Architecture is not bound by a promise of perfection, but rather by a legal and ethical “standard of care.” This distinction is more than just legal hygiene; it is psychological freedom. When teams silently commit themselves to an impossible standard, perfectionism ceases to be a driving force and begins to consume those who embrace it. Studies on perfectionism reveal that this maladaptive behavior pattern is linked to anxiety, depression, and burnout. In creative fields, this can mean slow decision-making, weakened collaboration, and missed opportunities. Saying “good and safe” instead of “perfect” keeps people human while maintaining the rigor of the work.

In practice, managing this means establishing boundaries early and frequently in writing. If a client requests something outside the brief, you document it, price it, and make a joint decision rather than silently striving for “perfection.” From AIA’s change order process to RIBA’s emphasis on change control, professional guidance exists precisely for this purpose: to prevent desires from turning into chaos. Clear agreements reduce the emotional burden that leads to compulsive reworking.

Revisions as Self-Sabotage

Revision is very important. However, after a certain point, each new revision yields fewer results and incurs higher costs. Behavioral research on choice overload shows how “more options” can reduce decision-making and satisfaction. In the creative version, a strong plan is replaced by a broad gallery of options that are very similar to each other, none of which can be implemented. The work seems intense, but the results stall. In practice, you can overcome this not by finding a mythical perfect iteration, but by setting “decision thresholds.”

Think of revision energy as another limited resource. Early cycles expand knowledge and reduce risk; late cycles, however, often replace clarity with confusion. A useful rule is to stop when changes are no longer tied to a measurable goal (comfort, cost, carbon, buildability) and instead focus on alleviating discomfort. That is the moment to test, validate, and hand over.

The Customer Feedback Loop Trap

If left unmanaged, it becomes a scope creep of good intentions. In project terms, scope creep is the silent expansion of requirements without budget, time, or risk planning; gold plating is adding unwanted extras. Both seem generous at the time, but later punish everyone. The solution is not defensiveness, but process. You define what is included, clarify how change requests are made, and put every request through a change control process that prices its impact and obtains approvals. This is not bureaucracy; it is the way to prevent creativity from becoming coercive.

There is a reason why the RIBA Work Plan requests approvals, freezes, and change control in Stage 3 and why AIA contracts formalize change orders. Uncontrolled cycles not only wear down morale but also ruin budgets. Analyses of capital projects consistently show that cost and schedule overruns are the norm, and that one reason for this is inadequate change management. Even public sector guidelines now see strict agreements and disciplined change control as the primary tools for mitigating damage. If you want freedom later, be strict at the beginning.

Final deadlines and design cycles

Time is not neutral. Parkinson’s Law reminds us that work tends to expand to fill the time allotted; the planning fallacy shows that we chronically underestimate how long complex tasks will take. Put these together, and you get the classic midnight cycle: You thought it would take a day, you gave it a week, and the task expanded to fit that timeframe without getting any better. Milestones, design freezes, and open “decision dates” exist to steer these biases toward delivery.

Healthy pressure is not desired; it is designed. RIBA’s design freeze concept and BSRIA’s Soft Landing approach encourage teams to make decisions early and implement them carefully, rather than endlessly revising the model. Treat the schedule like a material: reduce working hours to what the task truly requires; conduct reviews that answer a single question; close cycles in writing. Creativity thrives within these rails because they focus on outcomes—functional spaces for people—rather than constraints.

The Effects of Endless Revisions on Health

You may feel its effects on your body before you see them in your drawings: heavy eyes, slowed thinking, a strange haze mixed with progress. Health and design are not separate things; how you work shapes what you do. When correction becomes a lifestyle rather than a stage, it brings your sleep, stress, and judgment along with it. Research is clear: chronic sleep deprivation impairs thinking and mood; unmanaged workplace stress leads to burnout; high-pressure decisions made under stress lead us to make worse decisions. Architects and students are not exempt from this because their work is “creative.” In fact, the studio amplifies these effects.

Insomnia and Sketching Late at Night

Staying awake until the wee hours may seem heroic, but sleep deprivation is not a neutral state. Medical institutions warn that chronic sleep deprivation increases the risk of chronic health problems and directly negatively impacts your ability to think, react, learn, and relate to others. In creative work, these are the tools you need most. In short, when you cut back on sleep, the first thing to suffer is your brain’s renewal cycle.

The most appropriate comparison can be made with alcohol. Both classical and contemporary sources indicate that staying awake for approximately 17 hours has an effect equivalent to a blood alcohol level of 0.05%, while staying awake for 24 hours has an effect equivalent to approximately 0.10%. This is well above the legal driving limit in many places. This means that the culture of staying up all night wants you to design things like being slightly drunk and then hungover, and call it dedication. No matter how creative you think you are, you’re actually renting it out at a loss.

Architecture education has normalized this for a long time. AIAS reports and surveys describe a studio culture that celebrates “all-nighters” as a rite of passage, and independent reports have documented how widespread this is among students. Efforts to reform this culture in the field are ongoing, but in many places, this culture persists and has quietly become detrimental to workers.

Burnout Among Designers and Students

Burnout is not a state of mind; it has a definition. The World Health Organization classifies burnout as a professional phenomenon characterized by fatigue, cynicism, and decreased productivity, resulting from chronic workplace stress that cannot be successfully managed. If your weeks are filled with constantly delayed deadlines and endless changes, you are experiencing the conditions described by this definition.

In the field of architecture, warning lights are flashing early. Surveys conducted in the United Kingdom and reports in design media reveal that architecture students experience high levels of overnight work, stress, and help-seeking rates. This situation indicates that the path into the profession often begins with unhealthy norms. Efforts are being made by AIAS and schools to change this situation through studio policies, but constant attention is needed for change. When the education system accustoms people to disregard sleep and boundaries, companies also adopt this habit when hiring each new employee.

The practical result of this is not merely emotional. Burnout undermines the sensitivity and care that form the foundation of architecture. Recognizing this as a professional issue ensures that teams approach programs, scope, and staffing not just as work variables, but as health factors. This improves the work, not simplifies it.

Anxiety and Indecision in the Studio

High risks and shifting deadlines put a strain on the nervous system. Neuroscience shows that the prefrontal cortex, which we use for planning, working memory, and flexible thinking, is exceptionally sensitive to stress. Even mild and uncontrollable stress can quickly disrupt these functions; prolonged stress can alter neural structure. To put it in studio terms, this situation means a shift from sharp judgments to shaky second guesses.

Under stress, people tend to rely on their habits and instincts rather than choices made through conscious thought. Experiments show that we are less likely to change our initial judgments and tend to rely more on our unquestioned reactions. In the design process, this appears as a tendency to fall back on familiar actions because the brain cannot comfortably evaluate alternatives. You think you are “exploring,” but stress has unknowingly narrowed your field.

The Physiological Cost of Perfectionism

Perfectionism is not a single thing. Research distinguishes between “perfectionistic striving” (high standards that can be healthy) and “perfectionistic worrying” (fear of mistakes, harsh self-criticism). The latter is strongly linked to burnout; the former is not. This distinction matters in practice: a challenging standard can keep you focused; punitive self-criticism can break you down.

Costs manifest themselves both physically and mentally. Systematic studies link perfectionism anxieties to sleep disorders, while laboratory findings show that individuals with high levels of self-critical perfectionism exhibit higher stress reactivity and even increased cortisol levels while awake. Simply put, the more you view every correction as a judgment on your worth, the more “tense” your physiology remains, and the harder true improvement becomes. This is a cycle no project deserves.

This trend is becoming increasingly widespread. Long-term studies show that perfectionism has increased in recent years due to social factors. This means that young designers entering studios have a more critical approach towards themselves. Design culture did not create this trend, but it can either reinforce or mitigate it.

Design Fatigue: When Passion Becomes Toxic

Most architects love their work; passion is the reason they stay in this profession. However, psychology distinguishes between two types of passion. Harmonious passion is when your work aligns with your values and you can step away from it; obsessive passion is when your work controls you and takes over the rest of your life. Across various studies and fields, obsessive passion is linked to conflict and burnout, while compatible passion supports satisfaction and sustainable performance. If your “commitment” only works when you neglect sleep and your life, that’s not commitment—it’s a warning sign. PubMed

Obsessive passion and sleeplessness turn into a style, giving rise to design fatigue: every problem feels urgent, every revision feels like a moral imperative, and nothing is ever enough. This situation creates fragile decisions and joyless teams. The way out is not to care less, but to redefine what matters as something you can sustain over time: protect sleep like a material, define decision points like details, and evaluate scope as structure. Health is not the opposite of ambition; it is what enables ambition to be realized.

Excessive Design in the Built Environment

Buildings are designed to calm our nerves, not to grab our attention. However, when a project chases after showiness or adds systems beyond people’s real needs, the result is a space that looks impressive in photos but feels exhausting in real life. Research in environmental psychology and neuroarchitecture consistently reveals the same pattern: visual complexity and poorly designed environments increase cognitive load and stress, shaping our thinking, decision-making, and healing processes. In other words, it’s not a matter of “too much” style; it’s a health issue.

When Buildings Lose Their Human Touch

A human-centered building allows you to breathe, know where you are, and focus on what you came to do. When excessive design prevails, the opposite occurs. Excessive glare, echoing halls, and hyperactive interiors create a constant demand for attention that the brain must filter before it can do anything else. Studies on built environments show how visual density and unpredictability alter emotional state and cognitive effort, while lighter, more readable scenes aid relaxation. This is not an argument for emptiness; it reminds us that clarity and calmness are not luxuries, but functional qualities.

The results can be painfully real. In Las Vegas, the concave glass of the Vdara Hotel focused sunlight onto the pool terrace, creating such an intense “sunbeam convergence” that guests reported their hair catching fire and their skin burning; journalists and hotel management confirmed the incident and took precautions. In London, the 20 Fenchurch Street (“Walkie Talkie”) building reflected enough heat to blister paint, damage shop windows, and melt parts of a Jaguar until permanent sunshades were added. These are extreme examples, but they highlight a clear truth: When microclimate and user comfort are overlooked, architecture ceases to be a place of shelter and becomes a hazard.

Complexity Over Clarity in Floor Plans

In large buildings, especially hospitals and campuses, complex layout plans and inconsistent signage silently increase stress and cause time loss. Wayfinding research links disorientation to higher anxiety and lower task performance and identifies architectural factors: confusing intersections, repetitive corridors, inconsistent location markers, and signs that confuse rather than clarify. In recent years, evidence has grown from studies documenting how clearer plan logic and legible visual hierarchies reduce wayfinding errors and perceived stress. This is not just a graphic issue, but a planning issue: first place major movements on the floor plan, then use signage to confirm what the geometry already clearly shows.

Even if digital tools complete the navigation, they already deliver the best results in “logical” buildings. Industry guidelines for healthcare facilities emphasize that labyrinthine layouts increase anxiety at precisely the wrong moments; digital wayfinding can help, but it cannot fundamentally rescue an ambiguous plan. Designing for readability in advance is a healthier choice.

The Curse of Useless Ornamentation

Decoration is not bad; meaningless decoration is bad. The modern debate on ornamentation dates back at least to Adolf Loos’ polemical work “Ornament and Crime.” This work is a passionate call to abandon unnecessary ornamentation and advocate for honesty and moderation. Later, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown reshaped this debate by distinguishing between the “duck” (a building whose form is a symbol in itself) and the “ornamented hut” (a simple shell clarified by legible signs). Taken together, these two works offer a test for today’s excessive design: Does this ornamentation justify its existence by fulfilling a function of shading, signaling, protection, or guidance, or is it merely ostentatious? The latter results in lifelong maintenance costs and mental distraction.

Today’s applications make risks measurable. Detailed surface treatments and special facade features increase costs and operational risks without guaranteeing comfort or performance; when they do not serve a clear purpose such as sun control, bird safety, or wayfinding, they cause noise. The healthiest buildings treat ornamentation as a functional part of the system: a frit that prevents glare and collisions, a canopy that provides real shade, a sign that truly guides. Everything else is a burden. Weinberger, A. B., Christensen, A. P., Coburn, A., & Chatterjee, A. (2021). Psychological responses to buildings and natural landscapes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 77, 101676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101676

Excessive Use of Materials, Forms, and Features

Excessive design is also a carbon issue. Every additional coating, structural “just in case” layer, and technical layer creates a carbon footprint, and today there are clear targets to keep this footprint under control. RIBA’s 2030 Climate Challenge sets voluntary thresholds for operational energy and carbon footprint; LETI’s guide translates these targets into practical design options; RICS’s Whole Life Cycle Carbon Assessment standard turns the question “how much is too much” into a measurable life cycle question. When teams design forms and systems to the right scale, they are not just being fashionably minimalist; they are aligning with carbon budgets and making buildings easier to operate.

The same logic applies to performance claims. CIBSE TM54 was created because there can be significant differences between simulated and actual energy usage when complexity exceeds operational capabilities. Modeling with realistic hours, occupancy rates, and controls reduces surprises, and the simplest control that people can actually use is usually the most efficient. Constraint from a climate and human perspective is a virtue with measurable benefits.

Architectural Ego Revealed in Excessive Design

Cities sometimes commission or approve “iconic” objects in the hope of achieving a Bilbao-style economic revival, but the results are mixed. Critics and researchers have documented both the successes and failures of the so-called “Bilbao effect,” noting that mere spectacle rarely leads to sustainable revitalization and can hinder investments in the quality of daily life. When image takes center stage, user comfort and long-term management are pushed to the background.

The lesson to be learned here is not to ban ambition, but to channel it. London’s Walkie Talkie required renovation work after its glare damaged the street. New York’s Oculus, while drawing attention with its dazzling appearance, faced criticism due to excessive costs and recurring leaks. Both projects proved that headlines are not the final word. If a building’s story is mostly about itself, the people who live in it pay the price. Healthy architecture puts ego in the service of clarity, climate, and care.

Learning from Simplicity and Constraint

Simplicity in architecture is not simplicity for simplicity’s sake; it is about eliminating elements that do not serve a purpose, allowing those that do to breathe. The clearest projects feel inevitable when you stand within them; light, air, structure, and function come into focus effortlessly. There is also a practical side to this. As we scale forms and systems correctly, we get closer to our energy and carbon goals not just on paper, but in real buildings. The current guidelines are very clear: build only what you need, reuse as much as possible, and leave the heavy lifting of constraints to performance and cost considerations.

Minimalist Masters: From Mies to Murcutt

Mies van der Rohe’s work established a lasting standard of clarity. “Less is more” is not just a phrase, but a discipline evident in the Barcelona Pavilion and the Farnsworth House: a sensitive structure, surfaces reduced to their most fundamental elements, and a space filled with views that quietly guide and provide tranquility. When the constraints are this clear, you don’t miss what’s been removed; you feel what’s been revealed.

On another continent and in another climate, Glenn Murcutt demonstrates that simplicity is not a style, but a way of listening. His houses “gently touch the earth,” adapting to wind, sun, rain, and season using movable cladding and lightweight materials instead of heavy machinery. The Marika-Alderton House vividly illustrates this: raise the floor, open and close for monsoon and drought, and allow the architecture to change its character according to the weather. Here, constraint is not about scarcity but sensitivity.

Examples of Elegant Constraints

In Bordeaux, Lacaton & Vassal rejected the demolition decision and instead added large winter gardens and balconies to the social housing units built in the 1960s. Tenants preserved their homes; space, light, and air increased; and energy demand decreased because the new intermediate spaces balanced the climate. This is a clear moral lesson: transformation can be less costly than renovation and offer more livability.

A different approach to restraint is seen in Tadao Ando’s Church of Light. A simple concrete volume, sunlight cut in the shape of a cross, and almost no extra elements. Because there are few tools, the experience is very powerful. It shows that focus can be stronger than accumulation and that a single well-considered move can carry the entire building.

Pressure-Free, Purpose-Driven Design

Purposeful constraints begin by defining the outcomes you owe to people (comfort, clarity, low energy, easy maintenance) and ensuring the design responds directly to them. For this reason, many applications align early performance targets with carbon budgets and then design to meet them, rather than decorating afterward. Frameworks like RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge and LETI’s concrete carbon guide make this tangible: use less, reuse more, and direct your efforts measurably toward significant areas.

The process is as important as the ideals. An integrated, early decision-making process prevents teams from resorting to belated cosmetic changes and carries “soft landings” into the operational phase, ensuring that simple structures remain simple in use. Change control and clear phase transitions maintain this focus, transforming thousands of small, tempting options into a few responsible choices. Constraint is not a state of mind, but a workflow.

Regain Time with Simpler Methods

Indecision prolongs time. The practical solution is to make decisions earlier with better information and stop fixing parts that no one needs. The familiar MacLeamy logic reminds us: When the cost of change is low, direct your efforts forward; when change is painful, don’t direct them backward. Combine this with lean tools like the Last Planner System (short cycles, visible commitments, fewer surprises) and gain weeks without compromising the design.

How does this look in everyday life? Fewer personal details and more proven families. A smaller, clearer set of pieces. Reviews that answer a single question rather than reopening the entire plan. The result is not less creativity, but more energy for moves that truly shape the experience.

The Power of Leaving Things Half Done

Some of the most thoughtful buildings leave room for life to complete them. The Open Building theory defines this as “support and infill”: create a durable foundation and allow residents to adapt the layer they touch to suit themselves. Stewart Brand’s “sliceable layers” offer a similar perspective: allow the structure to move slowly and the furnishings to move quickly, so change can occur without disrupting what is permanent. In both views, today’s constraints enable tomorrow’s freedom.

There is a cultural wisdom in restraint. Japanese aesthetics gives voice to the value of gaps: ma, meaning meaningful pause or the space between objects. In design, this could mean leaving a wall empty so that light can speak, or finishing a detail without it becoming mannered. Unfinished edges are not neglect; they are an invitation for use, time, and weather to become co-authors. Buildings survive this way.

Toward a Healthier Architecture Practice

A healthier approach begins with a simple statement: Our way of working should make our buildings not only more beautiful but also more humane. This means treating the process as an integral part of the design. When the workflow respects bodies and time (clear stages, less reopening, longer support after delivery), projects become closer to their goals and people remain healthy enough to do their best work. Even health organizations are identifying the risks: The World Health Organization classifies burnout as an occupational syndrome caused by unmanaged workplace stress. If we don’t establish better habits in our architectural projects, the culture of architecture’s deadline can easily trigger this syndrome. Helpful frameworks already exist: phased planning, change control, realistic energy modeling, and soft landings that continue maintenance after opening day. Used together, they transform good intentions into healthier outcomes.

Knowing when to stop

Knowing when to stop is a design skill. This is not about lowering standards; it’s about making the right decision at the right time and then sticking to that decision. Formal “gates” help with this. The RIBA Work Plan requires teams to define gateways and clearly state what will be frozen and when, so that energy is spent on making the chosen plan work rather than constantly reopening the plan. Structural guidelines also add the same point in plain language: Adopt formal change control from Stage 3 onwards and track every change. This way, you can transform an ambiguous “enough” into a concrete milestone.

Stopping also means stopping the modeling cycle. CIBSE TM54 was written because many buildings fail to meet their energy targets during operation. This document ensures teams model with realistic hours, loads, and controls, so last-minute changes don’t appear to improve reality. When your assumptions align with how people will actually live and work, making further adjustments brings less value and more risk. Stop, document, and move forward.

Building Studio Cultures Resilient to Perfectionism

Perfectionism thrives in silence. The antidote is a studio culture that establishes healthy boundaries and puts them in writing. Architecture schools have grappled with this issue for years: AIAS’s studio culture studies expose the myth of all-nighters and compel schools to set clear expectations around time, safety, and respect. When practices adopt similar policies (regarding working hours, feedback frequency, and decision-making rights), people stop equating perfection with exhaustion. Burnout is not a personal failure; it is a predictable response to chronic stress. Treating burnout as an occupational hazard legitimizes better resource allocation and more honest work schedules.

Professional bodies are also supporting this change. RIBA’s workplace wellbeing guide recommends aligning pay, working hours, and culture to ensure employees are not forced into unpaid overtime. Such policies do not “make the job easier”; they make it possible to sustain quality over years rather than weeks.

Tools and Techniques for Efficient Design

Efficient design is not rushed; it is smart timing. The MacLeamy curve is a simple drawing with an important lesson: Decisions made early are cheaper and more effective than changes made late. Therefore, prioritize thinking. Use integrated project delivery to bring the right people together earlier, align incentives, and reduce late-stage changes that increase stress and cost. Combine this with lean tools in design, such as the Last Planner System (short, focused planning meetings, visible commitments, pull-based tasks), so teams spend less time putting out fires and more time on design.

After opening, close the loop. Post-use evaluation is not a luxury; it is the way to learn what really works in terms of energy, comfort, and usability, so that the next project starts more intelligently. Consider POE and the soft landing mindset that comes with it as part of the fee and part of the story you tell customers about quality.

Rethinking Success Beyond Aesthetic Excess

If success only means showmanship, then excessive design will always look like victory. Change the criteria, and things will change. The WELL Building Standard and performance ratings focus attention on air, light, acoustics, thermal comfort, and user experience—in other words, the things people actually feel every day. RIBA and its partners’ social value frameworks go even further, requiring teams to measure how a project improves the lives of users and neighbors. When civic trust, comfort, and health are counted as outcomes, restraint and clarity suddenly become a competitive advantage.

“Iconic buildings as tools for urban improvement” are no longer as convincing as they once were. Recent studies of the so-called Bilbao effect show that headline-grabbing architectural designs alone do not deliver lasting economic or social gains. A safer option is designs that enhance the quality of daily life, such as buildings that are highly functional, easy to use, low in operating costs, and generous to the street.

Design for Life — Yours and Others’

Architecture, in other words, is public health. How you organize light, air, and thresholds changes how people feel; how you organize work changes how teams live. AIA’s Equity Practice Guidelines address culture as a design issue within companies and suggest practical steps for more equitable, healthier workplaces. RIBA’s well-being guide also moves in the same direction, linking better conditions with better outcomes. Behind both is the WHO’s definition of burnout, which reminds us that unmanaged stress is not a transitional phase but a preventable harm.

Designing for life means leaving space for life. Define clearer boundaries so people can relax and buildings can open up. Bring projects to life so you can learn without blame. Celebrate buildings that are enjoyable to be in and easy to maintain. If we do this, success will move beyond looking like a flawless render to becoming a space that functions, a team that gets home on time, and a city that’s a little calmer because we added to it rather than shouting over it.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.