Public space is transforming from the backdrop of movement into the stage of daily life. The observational studies of William H. Whyte and Jan Gehl show that human-centered details (seating, food, shade, and edges) enliven social life and slow down the passage of time. Space creation built on these insights treats streets and squares not as finished objects, but as collaboratively created environments. The result is a public life designed on a human scale, not a car scale.

Cities now view streets as their largest public spaces and most flexible assets. While UN-Habitat defines public space as a driver of inclusivity and well-being, street design groups document how sidewalks, lanes, and squares can be quickly reprogrammed to meet new needs. This combination of policy and prototypes has turned public space into a lever for economic recovery, health, and equality.

The Changing Role of Public Space in My Urban Life

Public space has transformed into a scattered network consisting of several large squares and the daily living spaces between buildings. Gehl’s research on public life and global journals indicate that streets, libraries, cultural spaces, and even infrastructure now carry social meaning when designed for people. The character of the contemporary city is legible in these ordinary spaces.

This network must strike a balance between mobility, commerce, climate, and maintenance. UN-Habitat encourages cities to treat public space not merely as an area but as essential infrastructure, linking street quality to health, safety, and economic life. The more adaptable the network, the more resilient the city.

From Assembly Points to Transit Zones

Many terminals, airports, and shopping centers of the twentieth century became “non-places” built for efficiency rather than a sense of belonging. Anthropologist Marc Augé defined these spaces as places where users pass through but do not stay, anonymous and lacking in historical value. However, he himself acknowledged that encounters can transform a non-place into a place when social bonds are formed. Today’s task is to restore identity to these corridors.

Design tools such as “shared streets, station squares, and intersections without curbs” slow down traffic, prioritize pedestrians, and encourage interaction. As cities test layouts where eye contact and low speeds are more effective than signals alone, guidance emphasizes inclusive cues for people with disabilities. Transit zones are no longer just passageways; they begin to feel like destinations.

How Did COVID-19 Reshape Public Priorities?

The pandemic accelerated the tactical redesign of streets and sidewalks. Cities created quickly built bike lanes, expanded sidewalks, and open streets to maintain social distancing and support local commerce. New York’s open-air dining and open street programs transformed thousands of meters of sidewalks into public spaces. These initiatives demonstrated that urban life can be rapidly transformed through regulations and paint.

Health has come even closer to homes. While public health institutions promote the safe use of markets and streets, proximity models such as the 15-minute city have gained momentum; Bogotá’s rapid bike lane expansion has become a global benchmark, and parks have emerged as fundamental social infrastructure where equality gaps are revealed. People now expect accessible green spaces, local services, and safe transportation as fundamental civic rights.

The Rise of Hybrid and Flexible Usage Areas

Hybrid spaces blur categories: sidewalks become lunch spots, loading zones become dawn drop-off points, and evening marketplaces. Programs like parklets demonstrate how two parking spaces can become a small plaza, while sidewalk management guidelines formalize the creation of “flexible zones” at certain times of the day. Flexibility allows limited public space to serve more people with more functions.

Streets are increasingly being designed as programmable public spaces. Plans for adaptable sidewalks and shared street projects demonstrate how uses can be changed without the need for heavy construction work, allowing culture, commerce, and mobility to share the same stage throughout the day. The value of this lies not only in efficiency but also in identity shaped by recurring local rituals.

Public Space as an Extension of Civil Identity

Public spaces carry the face and voice of the city. UN-Habitat clearly states that well-planned streets and squares support social cohesion, civic identity, and quality of life. Recognizing these spaces and investing in them means investing in the city’s shared story.

This narrative is becoming increasingly local and intimate. With 15-minute city proximity agendas reshaping streets as the connective tissue of daily life, planning agencies are honoring places that embody community values. When design aligns with daily rhythms, public space becomes the city’s most compelling ambassador.

Design Principles Guiding Contemporary Interventions

Contemporary public space studies begin with people, treat time as a design material, and use landscape as fundamental infrastructure while keeping spaces open and safe. Global guidelines and street handbooks now frame public space not only through drawings but as a fundamental civic amenity measured and repeated by real-life usage. The result is an application that balances inclusivity, adaptability, climate responsiveness, and proportional safety as a single system.

Human-Centered and Inclusive Planning

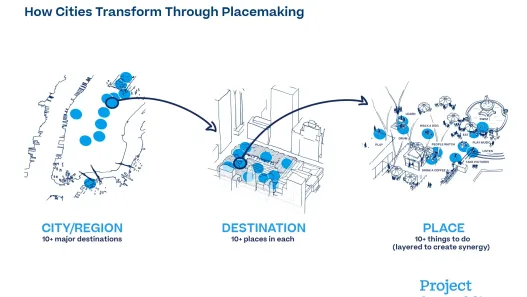

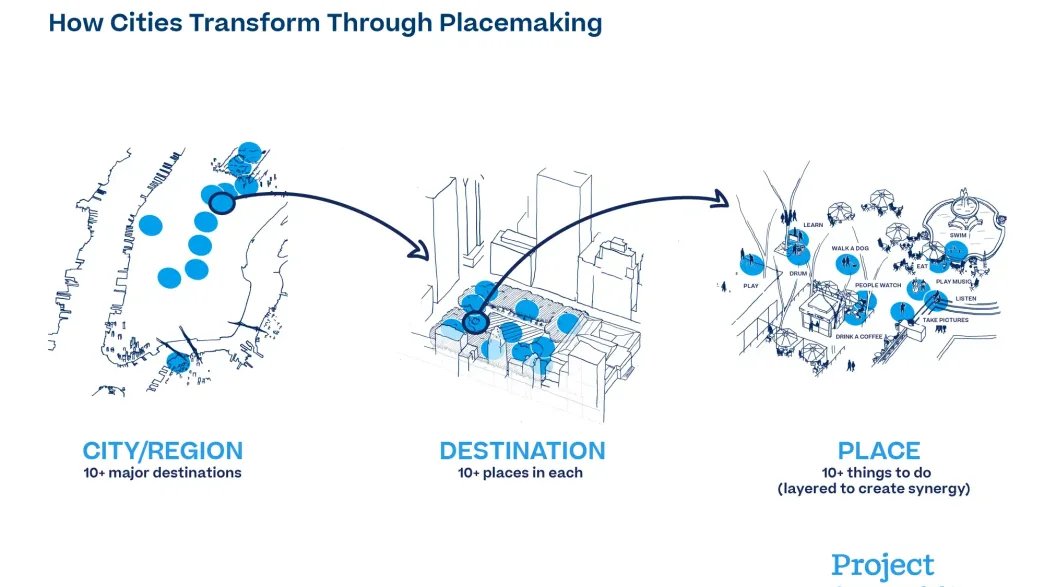

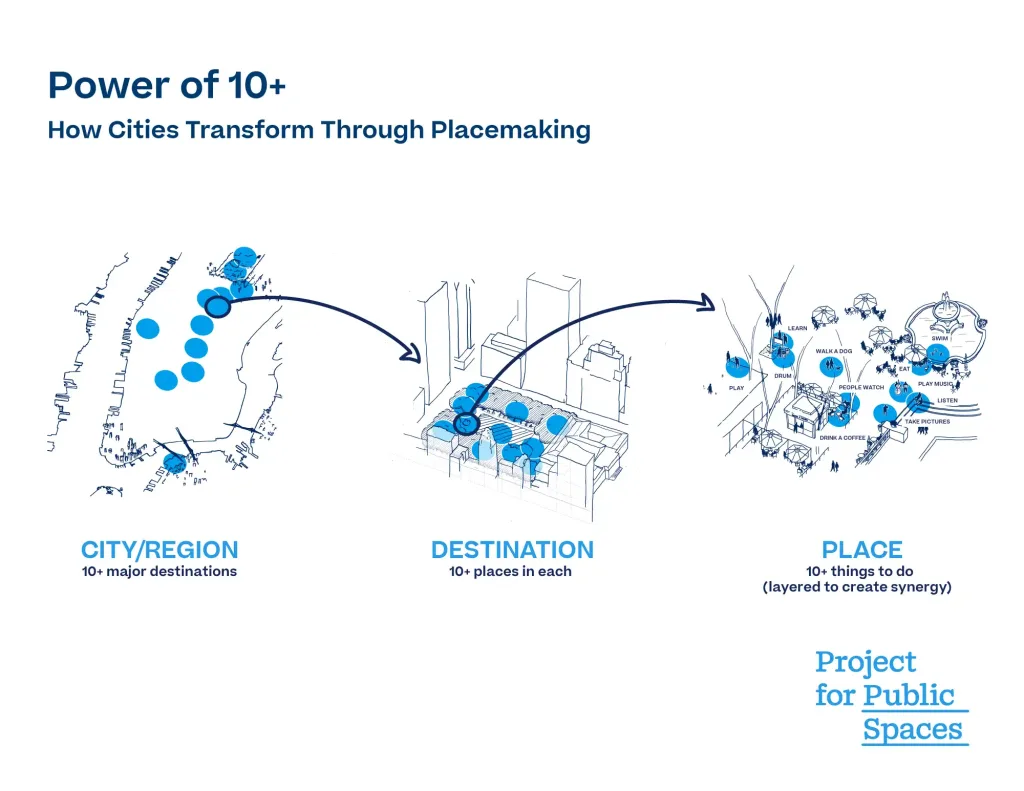

Human-centered planning examines how people use streets and squares, then organizes edges, seating areas, movements, and programming to support social life. Gehl and his partners’ public life methods make inclusivity observable by counting who stays, for how long, and why, among people of different ages and abilities. The WHO’s age-friendly agenda and the “Power of 10+” designers of place creation encourage the creation of spaces that offer many reasons to be there, not just to pass through. Inclusive intent becomes visible when different users choose to linger.

Temporary Use and Seasonal Adjustment

Cities are now planning not just square meters, but also hours and seasons. As sidewalks and streets transform into “flexible zones” depending on the time of day, programs like New York’s Open Restaurants have demonstrated that roads can be quickly transformed into public living spaces through regulations, paint, and simple structures. Winter city guides, incorporating the concept of microclimate, ensure that squares, streets, and edges remain inviting even during cold and dark months. Designing for time significantly enhances usability without requiring new land.

Landscape Integration and Climate Response

Landscape is no longer merely a decorative element; it is urban infrastructure for water, shade, and life. Blue-green infrastructure collects rainwater, cools streets, and restores habitat, while storm parks and “sponge city” tactics transform plazas and corridors into flood storage areas during heavy rainfall. Evidence shows that greener neighborhoods are linked to reduced heat risk and health benefits, transforming plantings from a comfort feature into a public health strategy. Climate-ready public spaces protect daily life and strengthen civic identity.

The Balance Between Security and Accessibility

City security is provided not by fences, but by elements such as furniture, plants, and ground shaping. Integrated security guidelines emphasize proportionate, context-based measures that keep spaces open while addressing vehicle threats; case studies such as Times Square combine granite benches and inconspicuous poles with wide pedestrian areas. Accessibility rules provide clear pathways, functional voids, and consistent surfaces, ensuring that protection never obstructs those who need public space the most. Security works best when perceived as comfort rather than control.

Architectural Strategies for Urban Renewal

Today, urban renewal is less about mega-projects and more about taking decisive, evidence-based steps that repair the fabric, build trust, and restore daily life. The most powerful strategies combine social outcomes with spatial skills: cleaning up and greening vacant lots, connecting edges for seamless movement, embedding memories into form, and programming spaces for ordinary use throughout the day.

Revitalizing Abandoned and Underutilized Land

Consider vacant lots not as land, but as public infrastructure. Randomized trials in Philadelphia have demonstrated that “clean and green” interventions applied to vacant lots reduce nearby gun violence and improve mental health, proving that small, replicable interventions can transform neighborhood-level safety and well-being. Programs like PHS LandCare in New York, GreenThumb in New York, and Keep Growing Detroit in Detroit transform thousands of lots into well-maintained gardens and small green spaces, fostering social connections and stable management. The formula is simple: clean, plant, fence, maintain; the impact is significant.

Incorporating Culture and Memory into Design

Places hold stories; renewal succeeds when design makes these stories legible. Dolores Hayden’s concept of “the power of place” advocates for urban landscapes that reveal marginalized histories, shaping conservation and new projects. From the community-selected works at Superkilen in Copenhagen to the National Peace and Justice Monument in Montgomery, projects that embody memory become as much a part of the civic fabric as parks or monuments. Even infrastructure restorations like the Cheonggyecheon Stream in Seoul combine ecology with memories, making the past walkable once more.

Creating Seamless Transitions Between Regions

Good curbs are wide, legible, and safe. The street design guide shows how curb extensions, open crossings, and active corners shorten distances and transform thresholds into places rather than barriers. When designers use streets without sidewalks or with shared surfaces, accessibility standards require tactile cues, perceptible warnings, and predictable routes to ensure everyone, especially people with visual impairments, can move safely. Continuity means having the right cues in the right places, not the absence of cues.

Design for Spontaneity and Everyday Use

Small changes keep cities vibrant between events. Whyte’s observations on public life show that seating areas, food, sun, and edges trigger unplanned social time, while modern street programs demonstrate that arrangements, paint, and light structures can reveal daily rituals. Open Streets and outdoor dining programs provide neighborhoods with flexible, seasonally breathing spaces by reprogramming sidewalks and lanes for gathering, eating, and playing. Spontaneity is planned by making setups easy, staying safe, and repeating simple.

Case Studies That Inspire Change

Each of these places demonstrates how sensitive design can reshape public life: by celebrating identity, reusing old infrastructure, consolidating social transformation, or connecting small spaces to a larger civic network. They showcase scalable methods such as participation, adaptable reuse, and incremental micro-interventions, along with the governance required to sustain their functionality over time. Together, they read like a guide for cities under pressure.

Superkilen Park, Copenhagen

Superkilen transformed a linear park into a vibrant catalog of the neighborhood’s cultures and installed everyday objects sourced from local residents to make a sense of belonging visible. BIG, Topotek1, and the SUPERFLEX team defined the project as “hyper-participation,” resulting in over 100 objects from more than 50 countries being placed in Nørrebro’s public space. The lesson here is simple: When people see their own stories in the shared spaces they inhabit, their sense of identity is strengthened.

High Line, New York City

An abandoned freight line has been transformed into a 1.45-mile-long park designed by James Corner Field Operations, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and Piet Oudolf, proving that old infrastructure can support a rich public life. Independent assessments show that this project has generated billions of dollars in new investment and over $1 billion in tax revenue, while also providing year-round usage and programming opportunities. The High Line also sowed the seeds for a global network of reuse projects and demonstrated how the careful choreography of civic governance and movements can transform a region.

Spain Library Park, Medellín

Giancarlo Mazzanti’s three “black stones” atop Santo Domingo Savio have become symbols of Medellín’s social urbanism: culture and education as engines of equality. Structural defects and prolonged reconstruction delays further complicated the story; the complex was renamed Parque Biblioteca Santo Domingo Savio, and as of 2025, the city continued to sign contracts for full recovery. The lasting lesson to be drawn is that iconic form must be matched with resilient delivery, maintenance, and transparent governance to earn the public’s trust.

Tokyo’s Micro Public Spaces

Tokyo demonstrates how a city can come together through small, overlooked elements. Projects like 2k540 Aki-Oka Artisan, which transform underpasses into artisan streets and daily shopping centers, while Kitaya Park in Shibuya offers an example of a small square that brings together greenery and neighborhood cafes. Municipal and civil society initiatives, by equipping sidewalks as “urban living rooms,” demonstrate how small, replicable steps can multiply comfort and usability across the entire network.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.