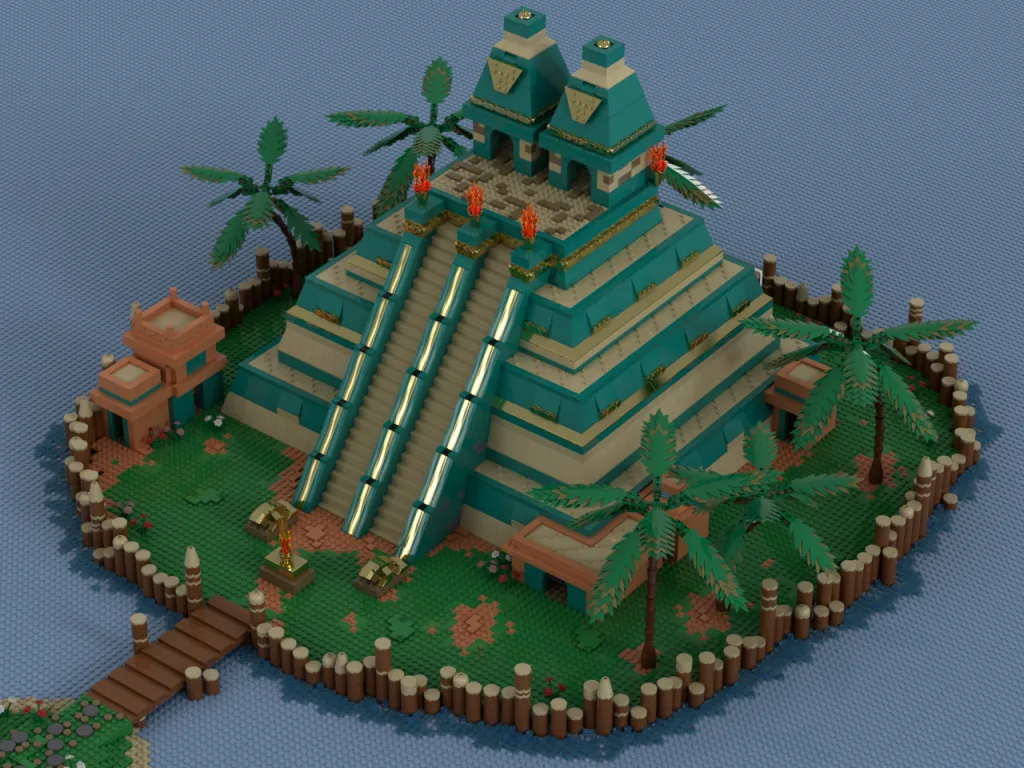

The majestic Aztec pyramids are much more than burial monuments: they encode the cosmological vision of their builders. For the Mexicans, the Great Pyramid ‘Huey Teocalli’ – the Great Temple – was the center of the ritual universe, a true axis mundi consisting of three levels (heaven, earth, and the underworld) where ‘the four corners of the world meet.’ This verticality is expressed by its stepped volume: the successive arrangement of platforms and stairways recreates the ascent from the earthly to the divine. As scholars have noted, pyramids were “artificial mountains that brought people closer to their gods in the sky.” At their summits were twin temples—one for Huitzilopochtli (the warrior god, the midday sun) in the south and Tlaloc (the rain god, the morning sun) in the north—thus reviving the legendary duality of the sacred mountains (Tonacatepetl/Coatlicue) in Aztec cosmology.

The orientation of the pyramid also reaffirms this celestial connection. The Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlán is aligned with astronomical events: recent studies show that the pyramid’s axes are marked by the sunset on April 9 and September 2, important dates in the Mexica calendar. Each step elevates the initiate to a higher level of the cosmos, and the pyramidal facades weave a stone dialogue between the world and the celestial vault by completely reversing the sun’s orbit. Thus, the simple geometric form is not arbitrary: it is a vertical cosmic map, a symbolic program written into the architectural design itself. As archaeologist Michel Graulich points out, the Aztec pyramid was “double” because it was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc at the same time, uniting opposites (sun and rain) in a single monument. In short, the pyramidal structure transposes the image of the pre-Hispanic world into stone: a hierarchical and tripartite cosmos where the monumental structure serves as a bridge between humans and gods…

Materials and environment: sustainability passed down from our ancestors

Despite their legendary appearance, Aztec pyramids were built in a pragmatic way, adapting to the lake environment. First, they used plenty of local materials: tezontl, a porous and lightweight volcanic rock, was the main building material for temples and platforms due to its high strength and ease of processing. In important walls, foundations, and load-bearing blocks, these igneous rocks were combined with hard basalt or andesite to leverage their strength. This arrangement reflects a thoughtful selection of geological resources: tezontle cavities that reduce weight and hold mortar, alternating with solid basalt layers for foundations.

Aztec engineers transformed the island of Tenochtitlán into an artificial solid structure. Modern photographs and illustrations of the Valley of Mexico show the city surrounded by canals and chinampas, highlighting the intrinsic relationship between water and architecture. Excavations conducted in the soft soil of Lake Texcoco have revealed that the Mexicans drove wooden stakes several meters high into the ground, then placed compacted earth and tezontle on top of them to support their buildings. As described by Fray Diego Durán, “they poured earth and stones between these stakes to form a foundation above the water… then they placed the foundations on top of this flooring.” This hybrid method—stakes + lake fill—created sturdy platforms above the mud; with each flood, the level rose by tons of material. In fact, recent studies indicate that the floor of the Templo Mayor in 1390 was approximately 9 meters lower than in 1521, reflecting over a century of continuous fill made of earth and tezontle.Aztec engineers transformed the island of Tenochtitlán into an artificial solid structure. Modern photographs and illustrations of the Valley of Mexico show the city surrounded by canals and chinampas, highlighting the intrinsic relationship between water and architecture. Excavations conducted in the soft soil of Lake Texcoco have revealed that the Mexicans drove wooden stakes several meters high into the ground, then placed compacted earth and tezontle on top of them to support their buildings. As described by Fray Diego Durán, “they poured earth and stones between these stakes to form a foundation above the water… then they placed the foundations on top of this flooring.” This hybrid method—stakes + lake fill—created sturdy platforms above the mud; with each flood, the level rose by tons of material. In fact, recent studies indicate that the floor of the Templo Mayor in 1390 was approximately 9 meters lower than in 1521, reflecting over a century of continuous fill made of earth and tezontle.

Hydraulic integration was even more sophisticated. The Mexicans designed chinampas (artificial islands) for planting and raised the soil while designing floating gardens that drained excess moisture and produced food. They built channels and dams (such as the famous Albarradón) to separate fresh and salt water and protect the city from high tides, creating an urban network in the middle of the water. This network facilitated the efficient transport of goods and people: canoes capable of carrying massive loads navigated the canals—a single paddler could transport approximately 1,200 kg in a canoe, which was 50 times more than what a person could carry on foot (23 kg).

Thus, the city was supplied and built in the best possible way using natural resources. These ancient strategies offer lessons in sustainability: the use of local volcanic stone (low transportation footprint), the use of floating foundations, and smart drainage are paradigms that are now being revived in many applications of passive and resilient architecture in today’s adverse climate conditions. In other words, Aztec construction techniques—from stepped slopes filled with volcanic ash to water-based foundations—anticipate modern challenges such as building on unstable ground or using efficient endemic materials.

Urban choreography: pyramids and social rituals

In Aztec cities, pyramids were not just closed bases: they were public stages that represented collective life. The main ceremonial area of Tenochtitlán was located in the center of the island, in a large stone-paved courtyard surrounded by walls. This sacred area was connected to the city through three portals aligned with the outer gates (Tepeyac to the north, Tlacopan to the west, and Iztapalapa to the south). These roads were not merely trade routes but also ceremonial axes: believers would walk or paddle along them to enter the religious center. Thus, the city plan manipulated the flow of people: crowds arriving through any of the gateways would enter the central ceremonial courtyard, where they were confronted by the grandeur of the temple.

The large square within the region was dominated by the Templo Mayor, with its double altar dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc on the east side. Other ritual buildings were scattered around it: to the north, the House of the Eagles (a place of penance for the tlatoanis); to the south, the temple of Tezcatlipoca; in front, the circular temple of Ehécatl-Quetzalcóatl and a ball court; and behind it stood the imposing Huey Tzompantli, a wall lined with the skulls of those who had been sacrificed. This complex functioned as a theater community. Social groups had their designated places: priests and rulers presided over ceremonies at the top of the pyramid, while the people filled the lower tiers. From there, they watched sacred performances: sacrifices, dances, ritual races, and parades were organized according to the cosmic calendar. In fact, chronicles and archaeologists note that “public ceremonies resembling the festive cycle of the Mexicans were periodically staged” in this great capital forum. The twin staircases of the pyramid led the way for the ceremonial procession: climbing these stairs symbolically meant ascending to the divine, and the ceremony culminated at the summit of the upper temple.

This hierarchical design defined an urban choreography: power descended from the sky to the people along a ritual route. Lower, flat, open areas encouraged mass participation, while the raised base of the pyramid imposed an experience of awe. As a result, pyramid temples were both domes of theological power and public arenas for political proclamation. Every sacrifice at the top echoed a collective message: it legitimized the tlatoani (ruler) with spilled blood and reminded the empire of the cosmic alliance that held it together. In other words, pyramids made social order visible: they indicated who was closest to the sacred and who must obey the rules of the cosmos, choreographing the flow of social life through architecture.

Modern Echoes: Pyramids in Contemporary Architecture

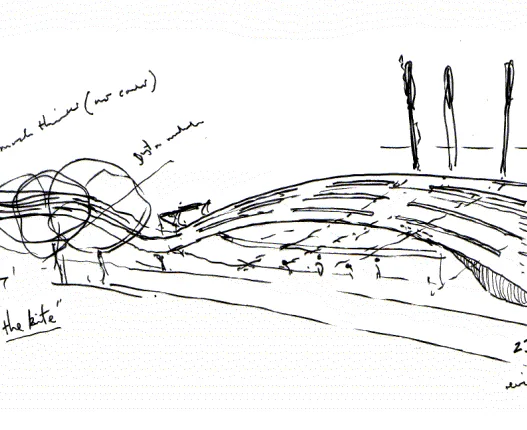

The influence of pyramids goes beyond archaeology: in Mexico and Latin America, they have influenced modern architecture not as direct copies, but through formal and symbolic resonance. Architects such as Luis Barragán or Pedro Ramírez Vázquez reinterpreted these elements—the idea of stepped volumes, the simplicity of exterior lines, or the play of light—through a contemporary lens. For example, Ramírez Vázquez embodied his deep respect for his Mesoamerican ancestors in the National Anthropology Museum (1964): he used natural stone “inspired by pre-Hispanic temples” as the basic material and arranged the pavilions around a large central courtyard reminiscent of the Maya quadrangle at Uxmal. By placing a base that evokes the Cuicuilco Pyramid in the entrance hall, he clearly linked the modern building to the ancestral pyramid. Similarly, the dramatic use of courtyards and light in Barragán’s works—as seen in Casa Gilardi or Capuchinas—evokes an atmosphere of silence and sacredness that many have compared to ancient temples.

Later architects integrated monumental structures inspired by the Aztec worldview without copying them exactly. Teodoro González de León built solid concrete walls and large courtyards. His work “embraced elements from the pre-Spanish past, such as large-scale structures that characterize his designs.” For him, the courtyard was not a decoration but a “central space for distribution, circulation, and encounter”—almost the same role. For him, the courtyard was not a decoration but a “central space for distribution, circulation, and encounter”—almost the same role as the Aztec ceremonial courtyard.

The Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) or the redevelopment of public spaces are concrete examples of this lineage: a collection of blind masses, ramps, and open volumes engage in a dialogue with the scale of the primitive temple. Even outside Mexico, the fascination with pyramids has influenced the thoughts of masters like Frank Lloyd Wright, who praised Mesoamerican architecture as “powerful and primitive abstractions of human nature.” This demonstrates that pyramidal geometry—born from a close relationship with the earth and embodying that “unblemished truth”—continues to serve as a stylistic and spiritual reference point for modernity.

This is by no means a matter of copying the past as a cliché. It is about recognizing a “geometric memory”: the emotional value of volumes and proportions linked to regional identity. As a result, adaptable reinterpretation is abundant in Latin America: from museums and monuments to residential buildings, pre-Hispanic ancestors can be seen in windows, courtyards, and orthogonal traces, reminding us that contemporary architecture itself is rooted in a heritage of stone and mortar.

Identity, power, and living memory

Today, Aztec pyramids continue to speak because they are monuments that embody identity and permanence. They are not limited to the past; their ruins and reinterpretations permeate today’s urban culture. For example, in 2021, the Mexico City government erected a giant replica of the Templo Mayor in the Zócalo, where a light show projected the ‘500-year history of the resistance of Mexico-Tenochtitlán’. Designed as a large pyramidal stage, the message was clear: the ruins do not merely tell the story of an empire’s collapse but also the enduring legacy of its heritage. Similarly, as part of the process of “decolonizing memory,” the names of urban areas have been changed, and colonial symbols have been removed (for example, “La Noche Triste” was renamed “La Noche Victoriosa,” and statues of Columbus were replaced with pre-Columbian figures).

These cultural efforts demonstrate that the pyramids today serve as symbols of power and resistance. The aim of each replica or official intervention is to celebrate indigenous origins and vindicate Mexico’s heritage. However, not everyone views this phenomenon the same way: Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, who played a key role in the rescue of the Templo Mayor, warned that such displays “do not truly strengthen our roots.” Nevertheless, it remains a fact that the temples continue to be integrated into public discourse. They act as living fossils of Mexican identity, reminding us that the nation was built upon this architectural dream.

The temples show remarkable resilience: many pyramids have withstood centuries of earthquakes and floods, sometimes remaining hidden beneath colonial plazas until archaeologists uncovered them. Thanks to rescue projects (such as the Templo Mayor Museum, opened in 1987 following Matos Moctezuma’s excavations), we can now literally step inside them, revealing them as active memory spaces. They are also still living scenes: today, thousands of visitors celebrate contemporary rituals, offerings, and festivals (from the Day of the Dead to civil events) on the ancient steps. In this way, the pyramids “speak to us” in every detail: in the grandeur of their forms, in the survival of their carved gods, in the stones worn by our modern hands. They remind us that architecture is more than function; architecture is legend, a connection to origins. As a thoughtful architect once warned, true construction “must look to the past to help give birth to new myths”: the Mesoamerican pyramids teach us exactly this and continue to embody the power, identity, and enduring legacy of a people whose voices still resonate through the stones.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.