Personal memory and collective trauma often give birth to a design. Architects often draw on their own history or community stories to sow the seeds of a concept.

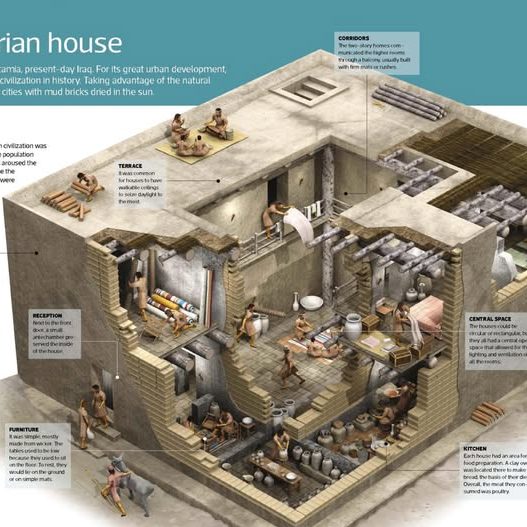

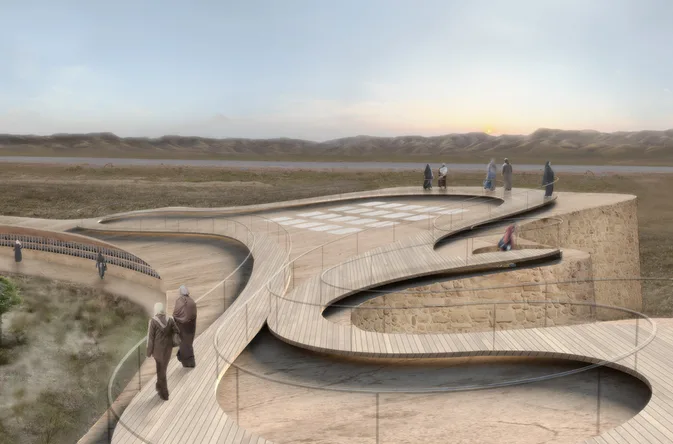

Before designing the Rizgary memorial in Iraq, Christoph Zeller and Ingrid Moye obtained detailed information about the atrocities of Anfal from survivors. They aimed to evoke an “oasis as a place of hope” amidst the desert wounds, using local stone and a low, horizontal form that “stretches horizontally… not vertically and uses local rocks in the facade”. Inside, 1,500 portraits of survivors are arranged in an endless circle, and a large central space (the reinterpreted courtyard) symbolizes loss and new life. In this way, a technical solution (a memorial building) becomes a tool for collective memory and healing.

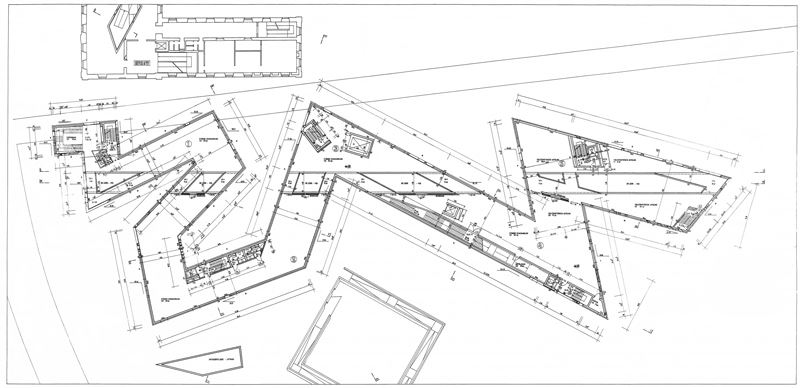

Libeskind’s Jewish Museum Berlin (1999) – its sharp, zigzag form (seen here from above) was clearly intended to “tell German-Jewish history”. Visitors experience disorientation or loss, interpreting the tilted walls and gaps as a broken Star of David or a thunderbolt.

At some point the sketch becomes a symbol or manifesto of identity. Instead of designing a museum building, Daniel Libeskind chose to tell the story of German-Jewish history. He achieved this by forcing its structure into jagged volumes and empty concrete “voids” (unconditioned spaces). The resulting building invites many meanings: some visitors see a shattered Star of David, others a lightning bolt.

The Invisible Atmosphere Senses, Mood and Memory

While a building’s form and materials are visible, architects increasingly recognize that invisible qualities – atmosphere, mood, sensory cues – are vital to the concept. Our memories of a place are often linked to smell and sound, not sight. Smell is a powerful trigger for memory construction. The distinctive smell of an old house can instantly revive childhood memories when revisited. In principle, therefore, a design can start with an intended atmosphere. An architect can choose an emotion (“serenity”, “dynamism”, “seriousness”) and create material, light and sound strategies to attract attention.

Neuroscience studies show that neglecting non-visual senses undermines well-being – sick building syndrome and seasonal affective disorder have been blamed on architecture that “tends to neglect non-visual senses such as hearing, smell, touch and even taste”. To counter this, some designers are now integrating every sense. Landscapes, tactile finishes, natural airflow and even carefully selected plants for scent.

In practice, intangibles often lead to early concept iterations. Order and proportion can shape mood: a narrow, dimly lit hallway can make people feel imprisoned, while a soaring, light-filled hall can evoke a sense of awe or freedom.

Recent commentary has noted that these invisible qualities – room proportions, flow and light – have a “powerful influence on how individuals interact with their environment”, affecting mood and social behavior. A well-placed opening, sound buffer or atrium can be as influential as the floor plan itself.

In short, we must understand that “design at its best is both seen and felt” and that often the most significant impacts on building occupants are those we can never see. This insight means that during concept development, an architect can sometimes prioritize atmosphere (silence, ventilation, an evocative smell) even before finalizing the visible form.

Materials, Narratives, Scarcity and Creativity

Some architects start with a material or technology in mind, while others start with a story, image or narrative. A heavy local stone floor may suggest a cave-like concept, while knowing the mythology of a region may suggest an abstract form. In both cases, available resources shape the direction. Today many designers are confronting material limits: an architecture of scarcity is emerging.

Projects now often minimize waste and reuse materials; in fact, creative constraint becomes a conceptual driving force. A designer can limit their design to a single material – concrete, wood or even recycled content – and allow this choice to inform form and assembly. Conversely, material-rich environments can lead to more expressive or monumental concepts, but risk excess.

Scarcity and abundance also shape scale and ambition. In a context where resources are scarce, architects can design modest, multifunctional spaces that make sense over time, while in boom times they can propose vast flagship buildings.

The important thing is that the concept evolves with resource awareness: an idea born out of necessity (a shelter using bricks) can produce unexpectedly poetic forms. In each case, architects try to balance their personal vision (a material fetish, a cultural leitmotif) with practical demands. They soften emotional bonds through constant criticism (through iterative modeling or peer review) to ensure that the concept remains buildable, usable and fit for purpose.

Balancing Personal Vision and Public Use

Architects walk a fine line between personal expression and the needs of users and communities. On the one hand, a concept often carries the architect’s own intention or narrative. On the other hand, buildings must also function for others. Research shows that architects aim to elicit certain emotions appropriate to a building’s function – for example, well-being in homes, safety in public spaces or monumentality in civic institutions.

This means that a design concept, no matter how personal, must ultimately align with the user experience. In practice, architects use both empathy and analysis and can invest in an idea (through sketching and visualization) but then use feedback to refine it.

This reflective process – answering the question “Does this building serve people?” – keeps the concept in balance.

Rituals and Spatial Order

From ancient temples to modern stadiums, ritual patterns often guide design. Architecture often involves ritualized movement and orientation.

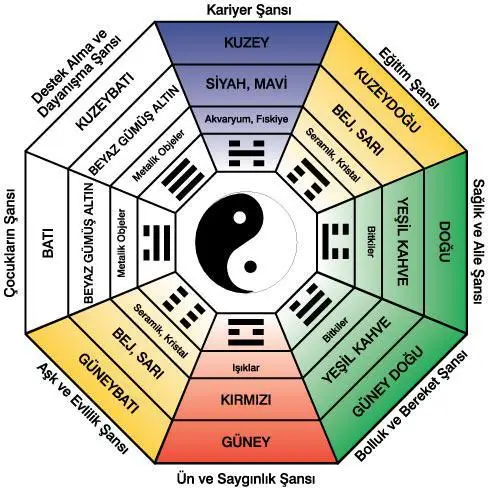

Traditional practices such as Vastu Shastra or Feng Shui prescribe seating and orientation to harmonize with the cosmic order; medieval cathedrals were aligned on an east-west axis to mark the sunrise on important feast days.

In each case, architecture uses form and order to guide rituals and give meaning to everyday life. Through ritual and myth, architecture “transforms meaningless chaos into meaningful order” and shapes how people move through space, gather and find purpose. Contemporary buildings continue this legacy: a town square for parades and public ceremonies, a university quadrangle for graduation ceremonies, a memorial grove for commemorations.

The courtyard of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence – a Renaissance colonnaded space that structures public “pilgrimage” through art. Architecturally, it directs movement and gathering in an orderly way.

Today, designers consciously refer to typologies of ritual space. A modern meditation hall might reflect the circular temple plan, or a memorial center might include a ceremonial pathway. Even secular routines – the morning commute, gathering for lunch – shape contemporary planning (the planning of plazas or shopping malls). In each case, the invisible logic of ritual (the sequence of events and meanings) is translated into walls, courtyards or sightlines. In this way, architects give new buildings a deep cultural resonance: they become stages for human rituals, old and new.

Concept Exploration, Intuition and Research

In architecture it is often debated whether concepts are invented or discovered. In reality both processes are intertwined. A designer may have an intuitive “vision” – perhaps ignited by a personal metaphor or a flash of insight – which then needs to be tested against reality. This can be as simple as a mood board or the translation of an abstract sketch into technical form. Intuition acts as a guiding spark, but research and analysis ground it. Inspired by the idea of “the flow of water”, an architect may initially shape curved walls, but then must blend the design of the space, user circulation or structural boundaries with the concept and end product expectations to refine this idea.

This collaboration between intuition and facts is intentional. Some architects follow Christopher Alexander’s idea that patterns exist somewhere, waiting to be “discovered”, while others embrace more conceptual inventions. In practice, a concept may emerge from studying the natural geometry of the site or reading its history, at which point the architect may feel that it has been “there all along”, or it may come from narrative imagination and only then be rationalized. Either way, a good concept should survive both creative inspiration and practical scrutiny.

The Role of Place, History and Ecology

A thorough site analysis is crucial before design. By studying the terrain, climate, vegetation and local culture, architects ensure that the planned concept fits the space. Site analysis helps “shape design decisions” by revealing the physical, environmental and socio-cultural characteristics of a site.

The sun path, prevailing winds and existing trees will influence massing, orientation and material choices. Similarly, knowledge of the history or ecology of the site often feeds into the concept: an old railroad track may inspire a linear building form, or natural vegetation may lead to dense use of wood.

Even the sense of smell or seasonal atmosphere can play a role – an architect may remember the salty smell of a coastal landscape or the cool earthiness of a forest and incorporate this into the design of the space. Designers strive for the new architecture to “blend well into its surroundings” as recommended in one analysis, so that the final designed building is perceived as belonging there and only there.

Cultural Context

The success of a concept depends on cultural adaptation. A form that is rich in meaning in one society may be incomprehensible or offensive in another.

For example, a color or symbol that is considered sacred in one culture may have very different connotations elsewhere. Recognizing this, architects must adapt concepts to the context while crossing cultural boundaries. In practice, this means that the concept phase includes narrative testing: architects ask, “Does this idea fit with local identity?” and sometimes completely revamp the concept. When it works, the building becomes a famous icon; when it clashes, it can be misunderstood or rejected.

Current Realities and Future Visions

The architectural concept is a negotiation between the visible present and the invisible future. It must solve current problems (zoning, budget, function) while at the same time envisioning future meanings (community use, heritage, adaptability). In a sense, the task of architects is to draft not only for today’s lens, but also for the imagination of future generations. A strong concept “discovers” the underlying qualities of a place and time, but also “invents” how they will be experienced years from now. Good architectural thinking juggles between these scales: channeling personal memory and cultural layers into forms that serve people in the here and now (invisible).

Conceptual design is deeply shaped by the hidden – the past we carry, the emotions we intend, the rituals we practice and the hopes we have. By bringing together theory and real projects across continents, we see architects becoming storytellers of space. Each line drawn emerges from this interplay of internal and external forces, creating buildings that are as much symbolic bridges to the future as they are responses to the present.