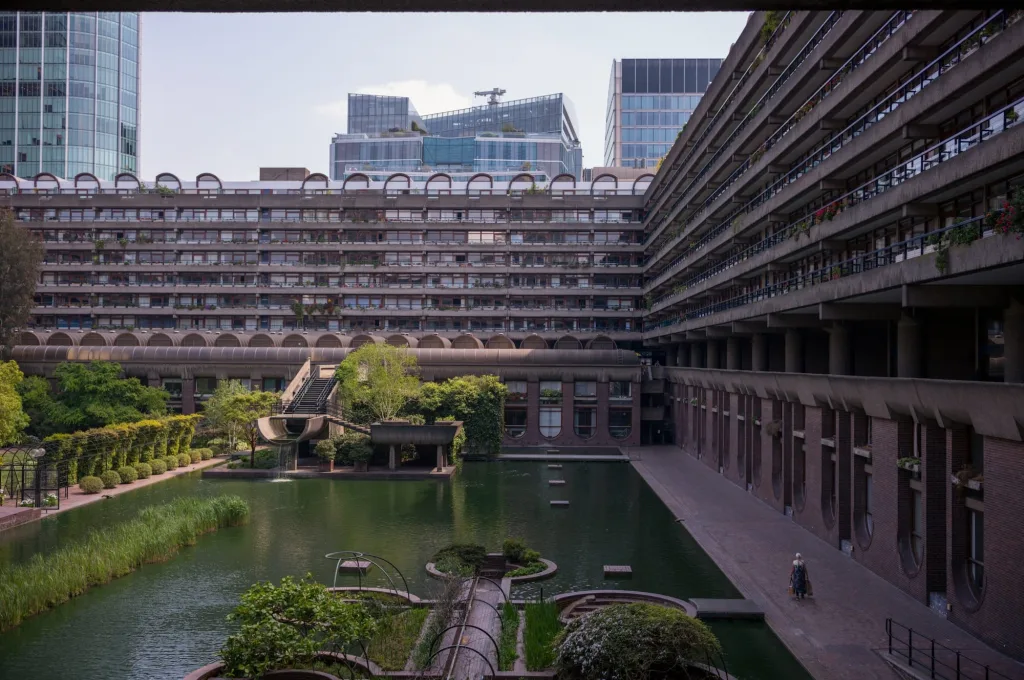

Figure: The Barbican Site in London (completed in 1976), where architects softened simple concrete volumes with private gardens and water features – “a soft visual foil to the seriousness of concrete”.

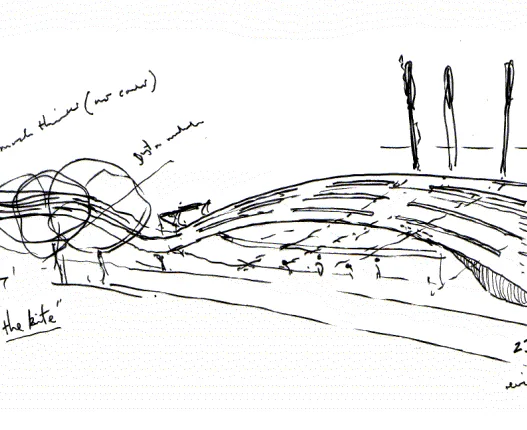

In recent years, Brutalism’s raw, unadorned concrete has gained an intriguing emotional appeal. What was once rejected as harsh or “inhuman” has become an object of nostalgia and admiration. Critics of the 1960s mocked these massive forms, comparing them to Soviet bunkers or prisons, but today even civil authorities and academics note a resurgence of affection. As demonstrated by London’s Barbican, designers initially embraced “béton brut” (raw concrete) for its honesty, balancing scale with greenery and water to humanize it. Now social media and the culture industry are celebrating Brutalism—it’s “adorned tea towels and mugs… and flooded Instagram accounts and coffee table books.” Decades after its heyday, Brutalism’s unvarnished aesthetic strikes many as authentic and poetic. This shift reflects a broader cultural transformation: a style once derided is now increasingly appreciated, even as many buildings face demolition. In short, the raw honesty of concrete that once repelled observers now evokes collective memory and curiosity.

How did Brutalism reflect the utopian social dreams of the mid-20th century?

Figure: Axonometric model of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation (Berlin version), showing the “vertical city” design with roof gardens, shared facilities (running track, pool, nursery, etc.), and integrated shops.

In the mid-20th century, Brutalism was not just an aesthetic style, but also a manifesto of social idealism. Architects believed that monumental concrete housing could rebuild society. Case studies clearly illustrate this. Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Gardens (London, 1972) are famous for their elevated walkways, known as “streets in the sky,” designed to combine the community spirit of Victorian slums with modern efficiency. The Smithsons argued that buildings should “reflect their inhabitants” and “encourage society,” in other words, serve as tools for social reform. Similarly, Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation (Marseille, 1952) was designed as a “city within a city.” The reinforced concrete tower housed not only apartments but also rooftop gardens, a kindergarten, a gymnasium, shops, and even a hotel—all optimized to foster an egalitarian way of life. For Le Corbusier and his successors, such shared elements were the “real infrastructure of utopia”: they embodied the mid-century promise that architecture could provide “collective luxury” and a dignified life for everyone.

Other Brutalist icons expressed similar ideals. Ernő Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower (London, 1972) included shared laundry rooms and balconies to encourage interaction between neighbors. Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 (Montreal, 1967) solved high-density living with light-filled communal spaces by assembling prefabricated concrete boxes into interlocking modules. As one commentator noted, Goldfinger and Safdie saw Brutalism not merely as a style but as a “moral project” aimed at creating affordable housing with shared public spaces and garden terraces. The Yale Art and Architecture Building (Paul Rudolph, 1963) similarly prioritized complex shared studios over luxury. These were concrete monuments to the post-war welfare state and the ethos of the “Great Society,” built on the belief that design could bring about social progress. We now mourn many of them: their demolition (such as Robin Hood Gardens) is often seen as the loss of a utopian dream, ironically in places where architects once promised “collective benefit”.

Why do we perceive brutalist buildings differently today compared to their original context?

Figure: Boston City Hall (1968) – An iconic example of Brutalist civil architecture in the US, now officially designated as a landmark for its “architectural, cultural, and civic significance.”

Age, wear and tear, and changing tastes have changed our perspective on Brutalism. Time has gently weathered many concrete facades, softening previous disdain. More importantly, public institutions and preservationists have begun to value buildings that were once scorned. Once mocked for its ugliness and slated for demolition, Boston City Hall was designated a protected landmark in 2023 and hailed as “a cornerstone of our city’s architectural and civic heritage.” Similarly, the London National Theatre (1976) was listed as a Grade II building just 18 years after its completion, and an open-air skate park once rejected as a symbol of social decay is now celebrated as “one of London’s largest public spaces.”

Figure: London National Theatre (1976) – tall, geometric concrete volumes (initially controversial) are now celebrated and protected as Grade II listed buildings.

These changes reflect Brunel’s observation: buildings that were once considered “unforgiving” gain value as they age. Initial criticism labeled Brutalist blocks as “inhuman,” “prison-like,” or “austere.” However, as this harsh context fades, people are finding its honesty and monumentality exciting. Many commentators point to this reversal: we often remind ourselves that the magnificent Victorian buildings we love were once considered hideous, and now we lament the loss of Brutalist gems. Examples abound—the once-maligned Trellick Tower is now a beloved landmark, and parts of Robin Hood Gardens have been purchased by the V&A as culturally significant. At its core, the public’s perspective has softened: what was once rejected as cold concrete is now valued for its uniqueness and sculptural drama.

Figure: Trellick Tower (1972) – Ernő Goldfinger’s high-rise apartment building was long derided as an “eyesore,” but now enjoys cult status as an architectural icon.

Is the Decline of Brutalism a Reflection of Our Changing Material and Cultural Values?

Figure: Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Gardens (London, 1972) before demolition – a Brutalist site consisting of concrete facades and elevated walkways. It was eventually demolished (2017) and replaced with traditional, glass-heavy towers, underscoring the shift in architectural taste. The decline of Brutalism actually parallels changing material trends. From the 1980s onwards, architects turned to lightweight steel and glass structures and high-tech surfaces, symbols of neoliberal optimism and consumer culture. Shiny towers and high-tech facades replaced gray concrete blocks, reflecting a preference for transparency and elegance. At the same time, the practical difficulties of raw concrete became apparent. As a conservation expert noted, many Brutalist buildings have faced aging issues: concrete slabs and precast panels have cracked due to corrosion, and uninsulated concrete walls fail to meet modern energy standards. Maintaining these massive structures has proven costly: the Boston University Law Tower is a famous example, where approximately 100 of the 700 precast concrete panels cracked due to reinforcing steel corrosion, necessitating their complete replacement rather than patch repairs. In short, property owners often conclude that demolishing aging Brutalist structures is cheaper than fully rehabilitating them.

These factors accelerated the decline of Brutalism. Critics observed that by the end of the 20th century, this style had “lost its luster”: it appeared overly simple and suffered from neglect. As a result, many projects met their demise (one analyst noted that many shared the same fate as Robin Hood Gardens). Ironically, the Robin Hood Gardens, designed with green terraces for tenants, were replaced by an even denser, glass-like development. This transition highlights our changing values: once we valued the social idealism of elevated walkways and private gardens; today, we value global sustainability and flexibility. Concrete, with its high carbon footprint, was once viewed as environmentally suspect. However, a new eco-conscious perspective is emerging. Architects are now exploring “eco-brutalism”: using recycled or low-carbon concrete, integrating vegetation, and even embedding photovoltaic panels into concrete elements. For example, Herzog & de Meuron’s “Solar Concrete Pavilion” points to a future where brutalist massing can align with sustainability by embedding solar panels within concrete blocks. The decline of Brutalism was partly driven by technical and cultural trends—from the rise of glass curtain walls to the challenges of preserving raw concrete—though new material science could potentially redefine concrete’s narrative.

Can the Basic Principles of Brutalism Be Redesigned for the Future?

Figure: Habitat 67, Montreal (1967) – Moshe Safdie’s iconic modular Brutalist residence. The interaction of concrete “bin-box” volumes (left) contrasts with contemporary designs that adapt Brutalist ideas to new materials and forms (right).

Despite Brutalism’s decline, its ideals live on. Contemporary architects are finding ways to channel Brutalist honesty and monumentality into new forms. Leading firms such as Herzog & de Meuron and Tadao Ando continue to use raw concrete or its ethos, but with advanced methods: for example, they are experimenting with low-carbon concrete mixtures, recycled content, and digitally produced molds to meet sustainability goals. Ando himself sees concrete not as oppressive, but as a humble material with “infinite possibilities,” and often uses smooth, sculptural concrete planes to evoke tranquility and solidity (a sensibility that has become fashionable in Japan and elsewhere). At the same time, interior designers and furniture manufacturers have also embraced the Brutalist aesthetic on a human scale. The latest trend in interior design, “Neo-Brutalist,” features blocky concrete and metal furniture: concrete table bases, stone-like sinks, and rough-cut metal lighting fixtures evoke the style’s geometry and textures. As observed by LuxDeco, designers are creating modern sculptural objects that reference Brutalism’s principle of structural honesty by using “blocky, monolithic silhouettes” and patina finishes.

Young architects are also inspired by Brutalism’s clarity of purpose. Many argue that Brutalism’s spirit—an architecture made up of “basic building blocks” for social purposes—can be adapted to new contexts, proposing bold, minimalist masses made of wood or compressed earth as analogues to concrete walls. For example, speculative co-housing designs often include shared courtyards or rooftop gardens (a nod to Unité and Robin Hood) but are constructed using sustainable materials. In furniture and art, creators like Kelly Wearstler and Amoia Studio are openly blending Brutalist textures (rough metal, carved stone) with luxury design pieces.

What we really miss may not be Brutalism’s concrete forms, but rather the ambition behind them—the belief in architecture’s power to shape society. Brutalism emerged from the belief that design could address housing shortages, equality, and society at large, a belief that is rarely seen today. As we mourn Brutalism, we may also be mourning an era of ideological courage. Contemporary reinterpretations—whether carbon-friendly concrete towers or sculptural furniture—show that designers are trying to recapture that same courage in different guises. Brutalism’s legacy lives on in every design that dares to be honest, monumental, and socially focused—qualities that are perhaps as important now as they were in the post-war world.

Further reading: For more in-depth information on the history and ideas of Brutalism, see Frédéric Migayrou’s The Brutalist Bible, Zupagrafika’s photo essay Brutal London and Sherban Cantacuzino’s books Concrete and Culture. Other sources include Justin McGuirk’s Concrete Concept, Reyner Banham’s The New Brutalism, and Barnabas Calder’s Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism. These explore the theory, legacy, and ongoing relationship of Brutalism with contemporary architecture.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.