Architecture also shapes how a nation is seen and felt. Political scientist Joseph Nye defines soft power as “the ability to influence others without coercion.” Buildings can do this slowly and steadily by promoting values such as openness, respect for culture, technical excellence, or environmental responsibility. When governments incorporate these values into embassies, museums, and airports—places where foreigners most frequently encounter them—they transform concrete, steel, and glass into silent diplomats.

In these three building types, design choices become policy signals. An embassy’s stance on transparency and security, a museum’s curatorial “voice,” an airport’s hospitality… All of these shape the impressions of outsiders and, over time, its reputation. Academics even propose methods for reading the “performance” of soft power through architecture’s position, meaning, message, promotion, and form of creation.

Understanding Soft Power Through Structured Forms

Soft power influences people by making them want to connect with you through appeal. In terms of national branding, it involves managing a country’s image to attract talent, tourism, investment, and goodwill. Architecture sits squarely at the heart of this strategy because it is both a symbol and a service: a representation of who you are and a place that serves people well. Global indices such as Brand Finance’s Soft Power Index and Anholt–Ipsos’s Nation Brands Index track these reputational effects over time, and the built environment is often part of the story that authorities promote.

A practical way to think about “soft power architecture” is a simple triad: place, program, and performance. Place = where and how the building is situated in the city. Program = what it offers (beyond the minimum). Performance = how it feels and functions on a daily basis. Cities that successfully bring these three elements together often transform their buildings into long-term trust machines. Consider Bilbao’s transformation from post-industrial decline to a global destination following its museum investment. This transformation was sustained through programming and urban improvements that went beyond the icon.

What is Soft Power and Why is it Important in Architecture?

Soft power is about creating appeal through culture, values, and ideas; it is not coercion. When a building embodies these qualities, it becomes part of a country’s diplomatic tools. Cultural diplomacy institutions define this as persuasion through shared culture; “brand” literature adds that countries compete for perceptions just like companies do. Therefore, the appearance, feel, and behavior of flagship buildings are important.

You can see the results in numbers and narratives. The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao is a classic example: striking architecture and carefully curated programs increased visitor numbers and economic impact in the Basque region. This is proof that a cultural project can reshape a place for the world (and its own residents). The lesson for design teams is modest: the building is the spark; sustainable soft power comes from what you do inside and around the building.

From Culture to Concrete: Architecture as Diplomacy

Embassies. Following attacks on US embassies in the late 1990s, security became a priority. Two decades later, the State Department’s OBO “Design Excellence” approach encourages teams to reconcile security with architectural quality and representation. The new U.S. Embassy in London, designed by KieranTimberlake, is an instructive example: the crystal cube within a landscape “moat” conceals defense systems while emphasizing openness and environmental performance; security is achieved through design, not barricades. In contrast, the ultra-secure Baghdad complex conveys a very different message with its fortress logic. These are policy choices expressed in site planning, facades, and public spaces.

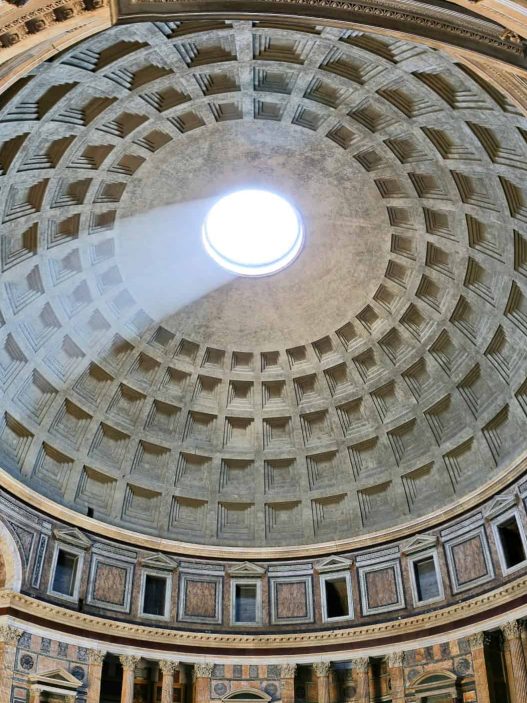

Museums. Louvre Abu Dhabi is a soft power made visible through an intergovernmental agreement: France licensed the Louvre name and expertise to the UAE for over €1 billion, creating a universal museum narrative under Jean Nouvel’s perforated “rain of light” dome. The museum’s positioning as a “bridge between civilizations” is cultural diplomacy in terms of program and brand. The Qatar National Museum, also designed by Nouvel, links geology with identity by using the desert rose shape as a national symbol. These formal choices reinforce the messages that governments reinforce through exhibitions and partnerships.

Airports. Airports are the first hello and last goodbye places. Singapore’s Changi Airport (along with Jewel) combines efficiency with pleasure to reinforce the country’s reputation for order and care; Beijing Daxing’s starfish-shaped terminal, opened around the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China, combines capacity with ostentatious ambition; Designed on a mega scale, Istanbul Airport is positioned as a symbol of national rise and hub strategy within the country. Wayfinding, daylight, queues, retail, and even gardens have become tools of national branding.

Symbolism, Perception, and National Identity

Symbols are useful when they are legible and lived. Nouvel’s “desert rose” designed for Qatar is legible, rooted in place and history. The embassy in London, on the other hand, is lived-in. Security is integrated, so the public space still feels open. These gestures point to stories people repeat: “Qatar as desert modernity,” “transparent but protected America.” National branding studies remind us that such symbols support a broader strategy but cannot replace the essence. The architect’s task is to make the symbol true to reality: to select forms, materials, and public interfaces that align with the country’s real values and behaviors.

A quick field guide for teams designing soft power buildings:

- Form as metaphor. If it will help foreigners “read” the space, use forms connected to the landscape or history (desert rose; radial plans resembling starfish, symbolizing connectedness).

- Signs of openness. Transparent facades, public squares, shaded edges, and visible art collections convey a welcome message when security is seamlessly integrated.

- Traveling program. Borrowed credibility (e.g., the Louvre agreement) or global-local co-curatorship can multiply access, but this is only possible when paired with sustainable content.

- Promised performance. Wayfinding, daylighting, acoustics, and inclusive design in airports and embassies are as much an ethical statement as they are technical; they say, “We care about how you move and feel here.” Changi’s brand strategy explicitly uses this.

Architecture gives people a body they can visit, photograph, queue up in, and remember. When countries invest in places that make them feel generous and competent, they not only reap rewards, but also gain patience, curiosity, and ultimately, friends.

Embassies: Castles or Invitations?

Embassy architecture walks a tightrope: it must keep people safe while also signaling openness, competence, and respect. The best designs conceal defensive elements in a visibly discreet manner; parks, plazas, and facades incorporate foldable distance maintainers, impact-resistant elements, and blast-resistant details that still convey a welcoming atmosphere. Since the embassy bombings of 1998, the US has moved from standardized “fortress” solutions to the Design Excellence approach, which asks architects to integrate security with urbanism and representation. This shift is being closely watched by other foreign ministries.

Security and Transparency in Embassy Design

Post-bombing evolution (SED → Design Excellence).

In the 2000s, the State Department adopted Standard Embassy Design (SED) prototypes that prioritized rapid delivery and enhanced security. Around 2011, the Office of Overseas Buildings Operations shifted toward “Design Excellence,” commissioning region-specific architecture that better represented the country while meeting stringent threat criteria. The goal here was not to compromise security, but to achieve it without sacrificing civilian presence, functionality, and life-cycle performance.

How do you conceal a fortress?

Designers now view the landscape and building facade as the first line of diplomacy. Sets, trenches, water features, low walls, lawns, and plant beds also function as blast-proof and impact-proof devices; second facades regulate glare, views, and privacy while protecting the solid curtain walls behind them. The goal is not a checkpoint, but to create a safe, legible, and generous space that looks like a park.

Reading “openness” from the street. Functionally “open” embassies do three things: (1) they keep public spaces active with paths, seating areas, and shade; (2) they make security continuous rather than intermittent (no sudden bottlenecks); and (3) they provide a wide view of doors and flags without theatrical barricades. When done well, visitors first feel welcome and only notice the security measures when they think about them. The landscape jury explicitly praises designs that provide “wide open vistas” while integrating security in an unobtrusive manner in its notes on recent projects.

The U.S. Embassy in London, Norway’s Transparent Embassy

U.S. Embassy, London (KieranTimberlake/OLIN) layering with openness.

The Nine Elms embassy building appears like a crystal cube with its high-performance glass walls and an exterior ETFE “sail” system that preserves daylight and views while reducing glare and heat. Symbolically transparent, technically robust. Around it, OLIN’s park-like area, using a pond, grassy mounds, benches, and fences, invites the public in while offering standoff and impact prevention performance. While critics have described the pond as “moat-like,” the design team frames it as stormwater infrastructure and a public amenity. Security and sustainability serve a dual purpose.

Lessons from the London example.

Security does not have to dominate the image. The landscape takes on most of the risks; the second layer of the facade provides comfort, privacy, and redundancy against explosions; the plan organizes the consulate queues without turning the front courtyard into a pen. Even skeptical critics acknowledge how defense systems are integrated into the language of urban gardens rather than being expressed as crude objects.

Norway’s “transparent” embassy in Berlin (Snøhetta) clarity and craftsmanship.

Located within the Nordic Embassies complex, the Norwegian embassy combines a building clad entirely in glass with a single granite monolith that connects it to Norwegian geology. The wider campus, encircled by a curved copper “band,” also includes Felleshus, a shared cultural center open to the public for exhibitions and events. The architectural message is clear: Scandinavian unity, openness, and material honesty form the foundation of a diplomatic space without compromising security.

Lessons from the Berlin example.

Transparency is not just about glass; it is about providing understandable thresholds and publicly accessible reasons for visiting. While Felleshus demonstrates how programming can carry soft power, the layered glass of the Norwegian building shows how a transparent facade can control the view, glare, and protection. Publications about the complex consistently emphasize how it feels light and inviting, despite intense security demands.

Security Design in Hostile Environments

Principles for “secure but civilized” embassies.

- First, the layered landscape: before adding hardware, the degree of shape, distance and rows for water and planting.

- Second coatings and screens: Use calibrated facades to manage the view and climate, and support them with sturdy glass.

- Continuous, non-episodic security: Add protections to every edge and approach, so that these are perceived as creative elements of the space rather than barriers.

- Design the environment: Galleries, gardens, and shaded paths symbolize hospitality and facilitate observation by making public life visible.

Governance and trade-offs.

Excellent design raises expectations and leads to greater scrutiny of cost and timing. While the State Department argues that better design improves representation, operations, durability, and total cost of ownership, oversight bodies have pointed to its impact on budget/timing. Lesson for clients: define criteria early (visitor experience, urban contribution, energy, security testing) and advocate for them throughout the procurement process.

Museums as Cultural Ambassadors

National museums are more than just places where objects are stored; they are tools of cultural diplomacy. They reflect values (openness, care for heritage, scientific rigor), host international exchanges, and give visitors a concrete “first impression” of a country’s story. Soft power experts argue that museums can work with governments to create centers of attraction, forging partnerships, shaping narratives, and building long-term goodwill. From a national branding perspective, museums are not just opportunities but strategic assets.

The Role of National Museums in Shaping Global Image

From collections to coalitions.

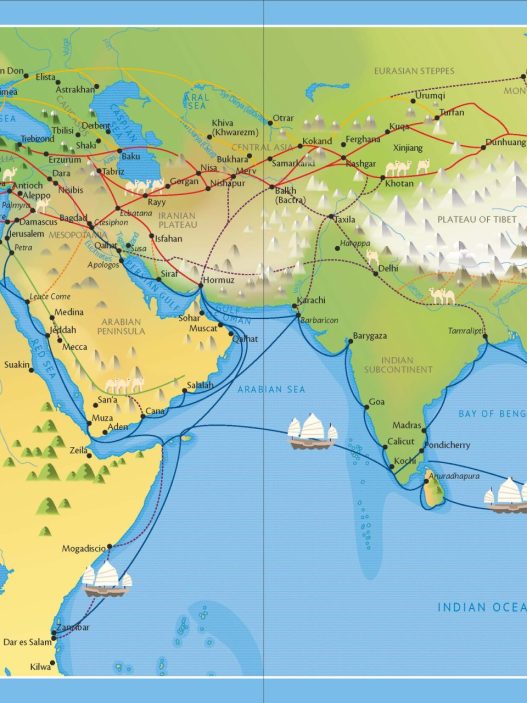

Modern national museums operate as cultural coalitions: lending, jointly curated exhibitions, and research fellowships combine local narratives with global ones. Louvre Abu Dhabi was explicitly designed as a “universal museum” with hundreds of annual loans from French partners. In this way, the exchange of objects became an exchange of prestige, and the UAE took its place in the global story of human creativity.

Mission statements as soft power scenarios.

A museum’s statement of purpose is part of how a nation wants to be seen. The mission of Qatar Museums is to “develop Qatar’s creative potential and cultural heritage… for every citizen, resident, and visitor,” linking its institutions to the country’s long-term national vision and turning exhibitions, education, and public programs into tools for identity formation and international outreach. Research on Qatar’s museum boom interprets this as cultural diplomacy serving legitimacy, regional leadership, and a cohesive Islamic identity.

Measuring the message.

Museums support national branding when they are understandable (visitors can grasp the story), connected (integrated into international networks), and consistent (programs align with stated values). The cultural diplomacy literature defines this as appeal through culture: a complementary channel to policy and trade that shapes how people feel about a place over time.

Iconic Examples: Louvre Abu Dhabi, Doha Museum of Islamic Art

Louvre Abu Dhabi license, loaned works, and “rain of light”.

The French-United Arab Emirates agreement behind Louvre Abu Dhabi includes a €400 million payment for the Louvre name (30 years of use) and significant commitments for loaned works, exhibitions, and advisory support, formalizing a decades-long cultural partnership. Jean Nouvel’s seaside “museum city” sits beneath a 180-meter dome. The dome’s perforations create the famous “rain of light,” casting dappled shadows like a contemporary mashrabiya. This effect is not only poetic but also diplomatic, uniting the Arabic architectural language and European museum practices in a single legible symbol.

The Doha Museum of Islamic Art is an abstracted tradition for a global audience.

I. M. Pei returned from retirement, traveled through the Islamic world, and was ultimately inspired by the ablution fountain at the Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo. He transformed the fountain’s simple geometry and play of sun and shadow into a stacked limestone silhouette on an artificial peninsula in the Gulf of Doha (opened in 2008). The result is an “Islamic” structure without pastiche: clean, modern volumes, carefully framed light, and galleries encompassing fourteen centuries of art.

Why are they important together?

When viewed side by side, the projects reveal two complementary strategies: borrowing and bridging (Louvre Abu Dhabi’s licensed name and loan networks) and distillation and proclamation (MIA’s transformation of its heritage into a contemporary symbol). Both transform architecture and curation into attractions, drawing the attention of academics, tourists, and the media, while also determining how their countries wish to be perceived.

Architectural Styles as Curated Identity

Form as message.

States often “regulate” identity through style. Nouvel’s design for the Louvre Abu Dhabi transforms the dome, a classic regional motif, into a climate-sensitive canopy that evokes both local and futuristic sensibilities. Pei’s MIA design transforms Islamic forms into pure geometry, allowing international visitors to feel the tradition without specialized knowledge. Each choice is strategic and translates culture into a clear visual language.

Material and light as cultural cues.

Limestone capturing the desert sun, calibrated openings filtering glare into patterned light, and shaded promenades along the water’s edge carry meaning beyond performance: symbols of hospitality, science, and craftsmanship. In Abu Dhabi, the “rain of light” has become a symbol of the country’s cultural transformation; in Doha, the shadow-carved volumes of the MIA are now synonymous with the city’s skyline.

Soft power test: readability + lived experience.

Identity only “settles” if viewers can read it and enjoy it, meaning the museum’s spaces, programs, and partnerships align consistently with the story implied by the building’s form. Cultural diplomacy research is clear: museums shape perception when they sustain change (lending, co-curating), maintain relevance (education, access), and embody values in their daily activities. Architecture sets the tone; those inside carry it forward.

Airports as Gateways

Airports are the world’s most visited public buildings and the first place where many travelers “get to know” a country. Designers and policymakers use terminals as a means of national expression, reflecting competence, creativity, and care in everything from wayfinding systems to gardens. Think of them as state ceremonial venues: spaces that move people quickly while also telling them who you are. That’s why industry benchmarks like the Skytrax World Airport Awards are important in terms of soft power; they are large-scale perception barometers of service and environment.

First Impressions: Airport Terminals as National Expressions

A terminal’s first impression begins from the outside: approach roads, transportation connections, and easily readable facades. Inside, daylight, clear routes, and intuitive signage create psychological comfort; many passengers later describe this as “efficiency.” These choices are not neutral; they concretely reflect national characteristics (order, hospitality, affinity for technology). Academics have generally defined aviation as an area of soft power and public diplomacy; here, infrastructure projects and passenger experience play a shared role in shaping image.

Awards and rankings reinforce this narrative. In 2024, Qatar’s Hamad International Airport (HIA) ranked first on Skytrax’s global list; in 2025, Singapore Changi rose back to first place, while Seoul Incheon ranked in the top five. These results convey a message of reliability and hospitality to millions of people. Airports achieve these results by combining bold architecture with service systems that passengers can immediately experience.

Spatial Efficiency, Luxury, and Hospitality as Soft Power Tools

Spatial efficiency builds trust. Shorter walking distances, clear sightlines, and smart transfer points reduce friction and anxiety. In practice, this looks like Incheon’s well-organized transfers and even transfer times for city transportation tours; it turns waiting time into a carefully crafted national example.

Luxury and grandeur create memories. Changi’s 40-meter Rain Vortex at Jewel reshapes the airport into a garden city communal space, while HIA’s biophilic “Orchard” transforms the shopping mall into a tropical greenhouse. Both are Instagram-worthy icons and microclimates that cool the crowd and slow the pulse. Unforgettable experiences that translate into increased prestige.

Hospitality and culture make the message clear. Incheon’s Korean Culture Street and heritage programs offer travelers a living culture; Changi’s gardens, hotel, and amenities position the airport as a city; while HIA’s expansion brings together food, art, and nature, positioning Doha as an elegant and hospitality-focused city. These choices come together to transform policy into emotion: tranquility, curiosity, and belonging.

Global Examples: Changi, Hamad, and Incheon Airports

Singapore Changi (SIN) “Garden City” has been made walkable.

Jewel’s Rain Vortex, at 40 meters high, is the world’s tallest indoor waterfall, connecting terminals and attracting not only travelers but also locals with its retail-garden hybrid. With terminal gardens, a butterfly habitat, and even a rooftop pool at the transit hotel on the airside, a brand embodying warmth and competence emerges. In 2025, Changi was named the world’s best airport (for the 13th time), reinforcing the soft power cycle of comfort, enjoyment, and global prestige.

Doha Hamad International Airport (DOH) is luxurious and biophilic.

HIA’s 2022 expansion introduced The Orchard, a large covered garden with a grid shell roof, featuring over 300 trees and more than 25,000 plants, blending nature with luxury retail stores and lounges. The project increased capacity (Phase A ~58 million passengers/year) and helped DOH win Skytrax’s “2024 World’s Best Airport” and “Best Airport Shopping” awards. This is a delicate soft power scenario: a tranquil space, carefully curated artworks and brands, and flawless operational service.

Seoul Incheon (ICN) efficiency where culture is showcased.

ICN combines clean, bright halls and seamless transfers with cultural touches. Traditional Cultural Centers, Korean Culture Street, and free transit tours make even a two-hour layover feel like a mini-visit. The airport ranked 3rd globally in 2024 and continues to rank among the top in 2025, frequently winning category awards (including being staff and family-friendly). This reinforces South Korea’s image of being hospitable, organized, and creative.

Design Strategies That Shape Perception

Design does not merely resemble something; it also tells a story. Our choices—such as how we blend materials, landscape, light, and tradition with innovation—teach visitors how to feel about a place and the people behind it. Research and standards provide a foundation for this intuition: from the tactility and cultural meaning of materials to daylight measurements (EN 17037; CIE standard sky), as well as public space safety, which also serves as an opportunity, and the UNESCO guidelines on integrating the new into the historic city.

Material Selection and Cultural Meanings

Materials are messages you can touch.

Stone, wood, metal, and clay carry stories related to landscape, craftsmanship, and belief. Architectural phenomenology (Pallasmaa) argues that texture, weight, and “materialized light” are elements that enable spaces to be felt and remembered; new research tracks how designers transform ordinary materials into cultural symbols that viewers can read. In short: the palette is a policy. Choose consciously.

Make the meaning clear based on the previous examples.

When Kengo Kuma stacked interlocking wooden “boxes” for the Odunpazarı Modern Museum in Eskişehir, he wasn’t being nostalgic; he was literally taking the space into account (“Odunpazarı” = wood market), scaling the volumes to match the surrounding Ottoman houses so that locals could recognize themselves in the museum’s structure. The result: a contemporary symbol that still feels like it belongs.

Develop local elements, don’t copy them.

Mashrabiya patterns are reappearing on facades worldwide like a second skin, due to their functionality (shade, privacy) and expressive power (regional identity). The Louvre Abu Dhabi’s eight-layered dome transforms the desert sun into a “rain of light,” turning a familiar motif into climate control and a cultural signal. That is the benchmark: updating craft to make it functional and communicative.

Landscapes, Lighting, and Local Integration

The landscape should have three functions: comfort, character, and protection.

The contemporary public space guide shows how land, vegetation, water, and seating areas can provide a choreography of distance and route without barriers. A method of “reducing the impact of hostile vehicles” disguised as a park. While perceived as hospitality rather than harshness, it quietly manages risk.

Design with daylight as people experience it. Combine this with CIE standard sky models when simulating different climates and orientations; what matters is not maximum lux, but comfort that tells a thoughtful story.

Integrate the building into the city’s living fabric.

UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape approach provides a practical checklist for integrating new developments into complex urban heritage. Read the city in layers (social, environmental, cultural) and respond at that scale. Gehl’s human-scale criteria for streets and squares (legibility, places to linger, shelter from the weather) help public spaces feel naturally inviting.

Adaptable Narratives: Blending Tradition with Innovation

Anchor innovation in the local context, then carry it forward.

“Critical regionalism” remains a useful compass: embrace modern techniques, but allow climate, craft, and topography to guide form and experience. Buildings gain credibility when innovations are built upon what already exists.

Consider reuse as an opportunity for soft power.

Adaptive reuse redefines a building’s public meaning while preserving memory and embodied carbon. Recent research shows that when design teams balance legal obstacles, working with hazardous materials, and financing with high-quality public programs, they accelerate urban renewal and cultural continuity. When done well, it means “we are preserving what is important and making it functional today.”

Create a prototype for the future with nature and light.

Airports and museums are testing grounds: biophilic waiting rooms, open-air terraces after security checks, and artistic daylight measurably reduce stress and enhance reputation. Evidence ranging from peer-reviewed research to industry reports supports what passengers already feel: generous sensory design is a diplomatic tool.

Challenges and Future Directions

Architecture can elevate a nation’s image, but it can also tarnish reputations, exclude communities, or lock cities into a carbon-intensive future. The next decade will be about designing for legitimacy as much as beauty: proving that the stories our buildings tell are true in terms of how they are financed, built, operated, and managed.

The Ethics of Creating an Image Through Architecture

“Soft power” projects carry real ethical risks. Cultural mega-projects are subject to criticism when workers’ rights are not protected (for example, the projects carried out on Saadiyat Island for the Louvre and Guggenheim museums in Abu Dhabi). This situation reminds clients that brand and construction ethics are inseparable.

Sponsorship can also distort cultural narratives. Years of activist pressure over fossil fuel financing have pushed UK institutions to rethink their partnerships (BP ended its long-term sponsorship of Tate; the British Museum’s ties remain controversial). The resignation of a board member at the Whitney in 2019 showed that boards themselves can become a public trust issue. The lesson here: Alignment between transparency and mission, and money, is now part of curatorial ethics.

Regarding representation, existing frameworks have already set a benchmark. The UNESCO Convention on the Diversity of Cultural Expressions protects cultural pluralism; the ICOM Code of Ethics sets standards for the accountability of museums to communities; and the Nara Authenticity Charter warns against superficial “copy-paste” identities and encourages context-specific interpretations of heritage. Architects and clients can base image creation on these norms rather than improvising.

Balance Function, Symbolism, and Sustainability

Buildings should first be functional, then symbolic. For airports and public symbolic structures, the entire life cycle performance has become the benchmark for authenticity. European standards (EN 15978) and design targets (RIBA 2030, aligned with LETI) compel teams to measure operational carbon from the beginning to the end of a building’s life cycle, transforming sustainability from a slogan into a specification.

The aviation sector is making this tension even more pronounced. While airports are committing to “net zero by 2050” (ACI), ICAO’s CORSIA program aims to limit the increase in international flight emissions through offsets and fuels. However, critics warn of greenwashing and credit shortfalls, even as industry leaders debate feasibility. For designers, this means prioritizing efficiency on the demand side (passenger flow, envelopes, energy, materials) rather than relying on future offsets to square the circle.

Symbolism is still important, but it must deliver value. The safest route is “functional meaning”: facades and landscapes that express culture while also delivering measurable and publishable outcomes in terms of climate, comfort, accessibility, and safety. (UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape guide offers a practical way to integrate new symbols into living cities without erasing local layers.)

Toward a Global Cultural Representation Code

There is no single binding “soft power design code,” but we can develop a reliable game plan based on existing international tools and industry standards:

- Joint creation and consent. In indigenous or culturally sensitive contexts, adopt the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) documented through representative institutions before, during, and after Design/Construction, with ongoing consent. Align the UNDRIP/UN guidelines with local laws.

- Authenticity and context. Use the Nara Document to test whether symbolism stems from pastiche or from place, craft, and use; apply UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape approach to reconcile heritage with change.

- Diversity and management. Align museum and cultural programs with the UNESCO Convention on Cultural Diversity and the ICOM Code of Ethics, including fair attribution, community access, and co-authorship of narratives.

- Labor and supply chain. Include worker rights among design criteria and conduct third-party audits in high-risk situations (Saadiyat-style debates demonstrate why this should not be open to debate). Publish audit reports alongside design awards.

- Climate by the numbers. Disclose carbon emissions throughout the entire life cycle according to EN 15978, follow RIBA 2030/LETI targets, and avoid relying solely on offsetting (especially in situations where market integrity is debated, such as CORSIA).

Customers, governments, and design teams accept these as minimum requirements and if they disclose them to the public, embassies, museums, and airports can be more than just an image: words on the wall.an değerlerin sahadaki uygulamalarla örtüştüğünün kanıtı haline gelirler.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.