Four thieves disguised as maintenance crew installed an elevator in the Cour Napoléon, broke a window on the second floor, and stole the crown jewels from the Apollo Gallery within minutes. Arrests were made, but this method exposed a security flaw that the design’s prestige could not conceal. The pyramid’s powerful central access system worked as intended, but the attack bypassed controlled entry, exploiting the vast palace grounds where cameras and intervention lines were inadequate. France immediately ordered an investigation, and the Senate emphasised that the Louvre’s security was “not up to modern standards,” highlighting the disconnect between the symbol and the system. The museum’s long-planned modernisation now includes enhanced surveillance, improved perimeter security, and the reorganisation of crowd flow.

Security Architecture: From Vision to Security Vulnerability

I.M. Pei’s Grand Louvre project transformed the vast palace into a single, unambiguous entrance beneath the glass pyramid, directing visitors into an underground corridor and then dispersing them to the wings. This was a masterstroke, combining symbolism and logistics, offering clarity and crowd control. Burglars did not target this front entrance; instead, they used a vertical wing where a basket lift reached an upper-floor window and where security camera coverage and response times were weaker. When the security concept focused on a single major bottleneck, the miles-long historic façade became a silent risk register. The state’s post-incident investigations and the museum’s “New Renaissance” plan reflect this rebalancing from internal flow to external resilience.

Security features incorporated into the original design

The pyramid did more than just announce a symbol; it concentrated access, ticketing and security checks into a compact centre that staff could observe and manage. Daylight from the pyramid and the lower-level hall provided controlled access to the wings while also facilitating orientation. This was security through legibility: reducing chaos, increasing control, and keeping the public space elegant rather than militarised. It succeeded as a gesture of citizenship and transformed visitors’ first movement from a queue into a procession. Its weakness lay not in the space it dominated, but in the surroundings it did not control.

Gap analysis: foreseeable threats and design assumptions

The assumptions are directed at threats arising from visitor flow, not climbing to the balcony window via the lift during daylight hours. Camera placement and viewing angles on the upper facades appear to have left blind spots; officials acknowledged this issue during calls to upgrade the equipment. The attackers’ strategy was speed, and the layout facilitated it: a short climb, a pause, targeted display cases, and a swift exit on motorcycles. These are predictable tactics in museum risk records, but difficult decisions regarding sensors, barriers, and elevated patrol routes in heritage sites are often postponed. This incident summarised the postponed decisions in seven or eight minutes of evidence.

How does historical architecture complicate modern security renovations?

As palace walls also serve as works of art, every camera, pole or laminated glass must comply with conservation rules, aesthetics and public safety. In such structures, the renewal of security systems is slower, more costly and more visible than in purpose-built museums. Therefore, when hardware is inadequate, upgrades based on standards and staff training become the primary means of protection. International museum organisations have warned that physical, technical and procedural security must develop together, especially in historical settings. Post-robbery investigations in France reveal how budget cycles and security debates can lag behind threat cycles. The Louvre’s renovation plan acknowledges this delay and seeks to address it.

How order, angles of view and design may have facilitated the robbery

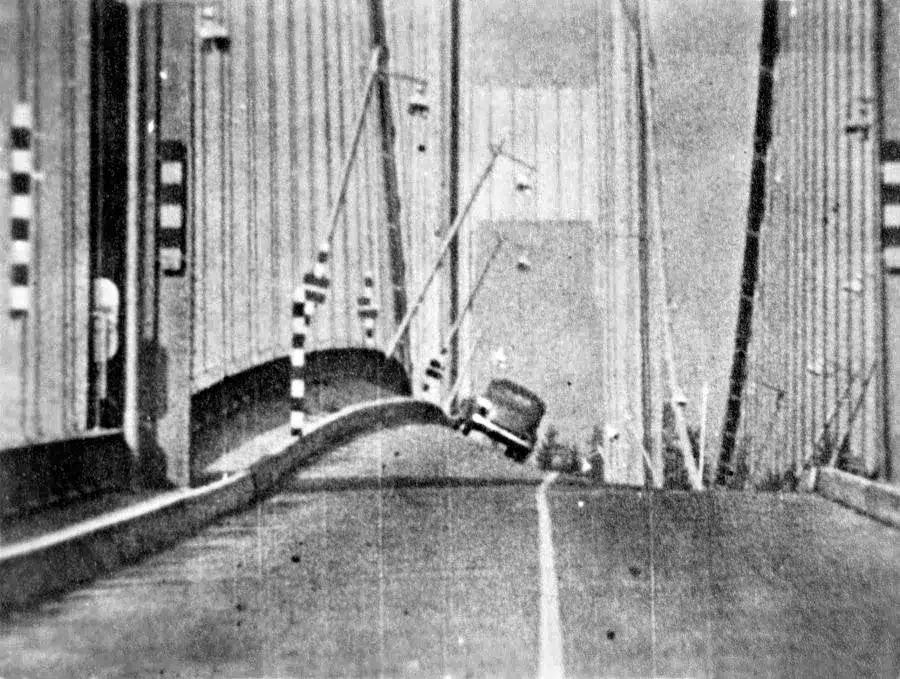

The Cour Napoléon is a large, open stage ideal for pyramids and crowds, as well as for a forklift that can easily reach the upper windows. Long enfilades suitable for ceremonies, such as the Apollo Gallery, create breathtaking views, but once passed, they offer high-value cases open axial paths. Reports point to weaknesses in the external camera coverage on the access balcony, turning a famous façade into a tactical weak point. Central control at the pyramid entrance drew personnel density inward, leaving the external area where attackers operated vulnerable. Architecturally, sightlines are bidirectional; beauty expands the field of view and sometimes the path.

The 2025 Robbery Incident: An Architectural Perspective

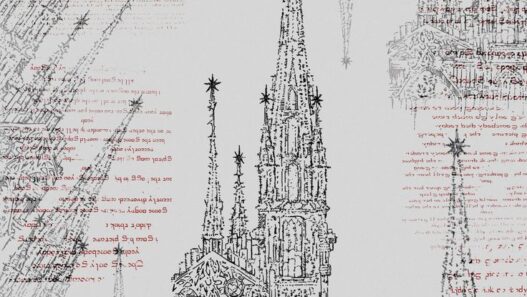

Summary of the robbery incident and stolen items

On 19 October 2025, four men dressed as workers entered the Galerie d’Apollon section of the Louvre Museum and carried out a jewellery theft in less than eight minutes. After dropping Empress Eugénie’s crown during their exit, they fled with eight historical pieces. The value of the stolen jewellery is approximately €88 million. Among the stolen items were emerald and sapphire crowns, necklaces and brooches associated with Marie-Louise, Marie-Amélie, Hortense and Eugénie. French authorities have arrested two suspects since that day, and the missing items have been placed on an international alert list due to fears of them being broken up. The incident prompted the French Senate and cultural authorities to conduct an intensive review of the museum’s security measures.

Entry and exit routes: how thieves move around the building

The attackers remained outside the main visitor building and instead moved vertically, using a basket or furniture lift to reach the first-floor balcony. They cut a window with power tools, entered the Apollo Gallery, reached their target display cases, and returned to street level via the same vertical route. Cones, vests and a work truck created a convincing scene that reduced suspicions in the open court. Two accomplices on scooters dispersed quickly throughout the city network. This route minimised the time spent in controlled indoor spaces while maximising speed along the building’s exterior.

Exploited vulnerabilities: building structure, access and surveillance errors

Reports indicate that incorrectly positioned or outdated external cameras, including those on the access balcony, limited detection and monitoring at the point where the breach occurred. The surroundings allowed a forklift to be parked close to the façade, transforming the ceremonial area into a temporary worksite. Leaders admitted it was a “terrible failure,” and senators said the museum’s security was “not up to modern standards.” This deficiency was not only technical but also procedural; heritage restrictions and slow upgrade cycles slowed the response to rapid, vehicle-assisted unauthorised entries. The result was a classic example of external security vulnerabilities overriding internal controls.

The role of ‘design friction’ – how architecture reduces or increases risk

Design friction is the sum of small resistances that slow down malicious individuals: distance, visibility, height, and reliable interruptions. Here, friction was low on the vertical envelope because the open courtyard area allowed clear access for vehicles and a breakable wing window. Inside, the gallery’s axial clarity supported speed after the display glass was cut, while the central scan in the pyramid did not interfere with the attackers’ route. The robbery demonstrates how iconic legibility can be separated from perimeter resistance when controls are lacking in the outer layers. The architecture set the stage for welcome and spectacle, and the thieves read the stage instructions better than the defence team.

Learning for Architects: The Paradox of Design, Conservation and Transparency

Striking a balance between openness and reinforcement in museum architecture

Major museums promise hospitality, clarity and civic pride, but they are also high-value targets frequented by large numbers of people and require multi-layered protection. The current guide advocates creating a visible space using landscape, layout and furniture to increase effort and reduce speed without turning squares into fortresses, employing unobtrusive security measures. This is the practical convergence of CPTED and HVM: natural surveillance and access control are combined with proportionate measures that are perceived as public space rather than barriers. While openness remains a primary goal, it must be structured to reduce risk to a reasonable extent. Architects hold the pen to make security nearly invisible or deliberately legible, depending on the context and threat.

Renovation of historic sites: what design can (and cannot) solve

Historic structures carry legal obligations and ethical constraints, so every camera, pole and laminated glass panel must take into account issues of authenticity, context and approval. Conservation regulations remind us that interventions must be minimal, reversible and respectful of the original material; this slows down the necessary conservation work, but should not stop it. Heritage institutions now publish security and counter-terrorism guidelines that treat compliance as part of the management task, while warning that many measures will require official permission. Consequently, good restoration work shifts the emphasis to planning, maintenance, personnel and procedures, with hardware being used where it provides real marginal gain. In short, design can reduce exposure risk, but governance and maintenance regimes must fill the remaining gap.

Strategic thinking: integrating spatial, material and technological layers in terms of security

Effective security should not be added at the last minute, but integrated at an early stage and spread across the space, materials, technology and people. Spatially, the aim is to create understandable routes, controlled approaches and friction in the environment to make speed and surprises more difficult; in terms of materials, performance-rated assemblies that alter time equations should be used; technologically, detection, delay and response should be harmonised. National authorities frame this as proportionate, site-specific design that improves the environment, remains inclusive, and is sustainable over time. Combine this with museum institutions’ risk management cycles, so that upgrades follow evolving threats rather than past events. The result is a system that fails safely, buys time, and presents a clear scenario to trained personnel.

Looking to the future: resilience, adaptability and architecture’s changing role in preserving cultural heritage

The lesson to be learned from recent theft incidents is not to harden everything, but to design for alignment with budgets and governance that update sensors, coverage areas, and playbooks as tactics change. International museum networks treat security not as a back-office service but as a living competency, and policy changes in legislation concerning crowded places are constantly raising the baseline standards for preparedness. Architecture can lead the way by reserving space for future hardware, providing conduits and data pathways, and shaping public spaces that also function as calm, defensible areas during incidents. The cultural mission remains intact, the environment becomes smarter, and the building transforms from a static shell into a living security platform. Transparency survives in this way without becoming an easy map for the next attack.