Learning from the Past: Architectural Optimism Throughout History

When architects in 15th-century Italy returned to classical ideas, they did not merely copy old forms; they rebuilt confidence in what buildings could do for people. Humanism placed the individual (vision, movement, comfort) at the center of design. Symmetry and proportion were not abstract concepts; they were tools used to make spaces calm, understandable, and dignified after a turbulent medieval period. You can feel this optimism in the clear-arched galleries and measured rooms of early Renaissance works, where geometry serves humanity rather than intimidating it.

The change was not only philosophical; it was also significant from a technical standpoint. Filippo Brunelleschi and his colleagues used modular proportions to create a harmony that you can experience with your feet. At the Ospedale degli Innocenti, a simple unit repeated along columns and arches transforms walking through the portico into a regular rhythm and a human-scale experience. This was not style for style’s sake; it was a system that allowed order, light, and movement to work together.

Today, when we talk about “human-centered” design—welcoming entrances, guiding daylight, intuitive rooms—we are echoing the priorities of the Renaissance. This era’s emphasis on clarity and balance continues to shape public buildings and squares, reminding us that optimism often begins with creating spaces that are more pleasant to the senses and easier to navigate.

Post-War Reconstruction and the Rise of Modernism

During World War II, cities were devastated, and architecture had to respond quickly to this situation. Governments aimed to combine social progress with efficient construction, granting planners the authority to build new cities and rehouse millions of people. In the UK, the 1946 New Towns Act established development corporations to design new settlements such as Stevenage. This proved that policy and design could work together on a national scale when there was strong public support.

On the ground, optimism showed itself through bold experiments. Rotterdam’s pedestrian street Lijnbaan proposed a new idea for a bombed-out center: giving the street back to people, separating cars, and creating a vibrant commercial hub that would support recovery. It wasn’t a perfect solution, but it demonstrated how a city could quickly reinvent itself through clear urban design initiatives and a shared civic will.

The long-term impact of this period remains significant. The industrial building methods and standards that took shape during and after the reconstruction laid the groundwork for energy codes and performance-based thinking. Following the 1973 oil crisis, the US published ASHRAE 90-1975, the first national model energy standard, setting efficiency expectations that continue to evolve today. The lesson to be learned here is encouraging: When crises clarify goals, design and policy can act in concert to reduce waste and improve daily life.

Futurism and Visionary Designs of the 20th Century

Some optimism comes too soon. Antonio Sant’Elia’s 1914 futurist manifesto envisioned a city built for speed, electricity, and constant change. His drawings, titled La città nuova (The New City), were not plans to be built immediately; they were a wake-up call, reminding us that architecture could keep pace with the tempo of modern life rather than copying the past. Even if they were never built, these ideas expanded the realm of possibility by transcending mental boundaries.

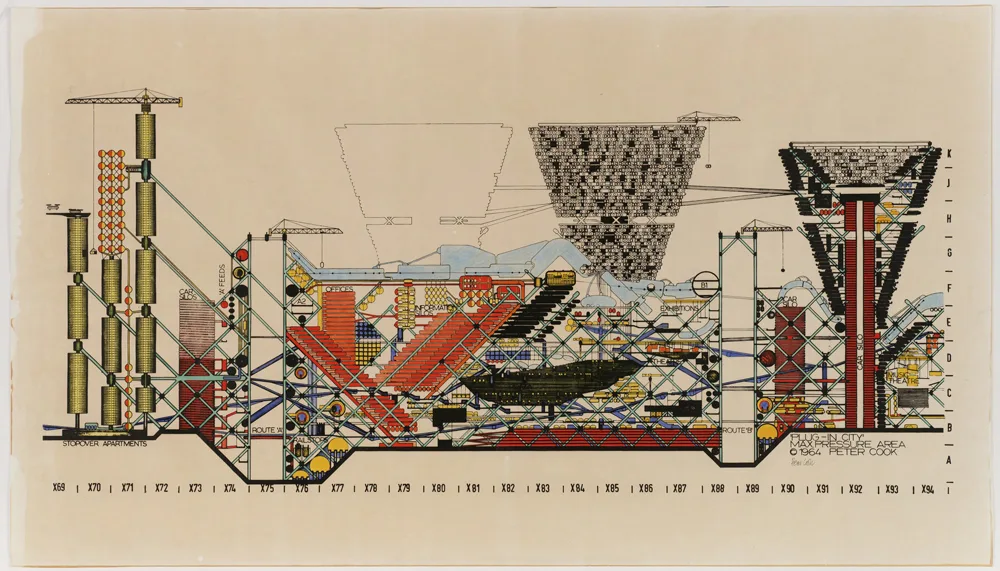

Half a century later, Archigram took up this banner with visions such as Plug-In City. Plug-In City was an urban mega-structure where services and housing could be swapped and plugged in like components. What mattered was not accuracy, but agility. By designing a city that could adapt to the pace of people’s lives, Archigram transformed design from a finished object into an open platform for constant change. This mindset continues to inspire today’s modular systems and circular building concepts.

Visionary prototypes have also been transformed into real structures. Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes proved that large volumes could be covered with lightweight components and minimal material. This principle continues to serve as an inspiration for efficient enclosed spaces and temporary structures. The optimism here is practical: when technologies and needs align, radical ideas can be translated from paper to pavilions and everyday buildings.

Bioclimatic Traditions in Regional Architecture

Long before the term “net zero” entered our vocabulary, people preferred to live in harmony with the climate rather than fight against it. Courtyards, thick walls, small high openings, and shaded galleries provided cool air, filtered light, and thermal stability in hot and arid regions. These were not traditions; they were sophisticated environmental tools tailored to the sun, wind, and materials. Recent studies synthesizing decades of research show how such local strategies effectively provide natural ventilation and temperature control.

Consider wind catchers (Persian badgir and Arabic malqaf) that draw wind into rooms and expel hot air using buoyancy. Or consider courtyards surrounded by plants, which balance extreme temperatures through shade, evaporation, and the cooling effect of the night sky. Contemporary studies validate their physical properties and performance, transforming them into a library of proven techniques ready to be adapted into modern building envelopes and control systems.

Today, architects are updating this old logic by adding functional shafts to dense plans, designing perforated facades that act like smart sunshades, or placing rooms in courtyards surrounded by plants to cool the air before it reaches occupants. This optimism is grounded: By remembering how well low-tech systems can work and combining them with the best new materials and sensors, the future becomes more manageable.

Crisis and Rediscovery: Historical Cycles

Every era faces a shock that necessitates the construction of better buildings. After the Great Fire of London in 1666, the city needed brick and stone for reconstruction and restricted the height and density of houses. The rules changed because reality demanded it, and as a result, structures became safer. This cycle is familiar: danger makes norms visible; policies and practices are redefined; the city evolves.

Energy crises also had the same impact on performance. The 1973 oil embargo forced governments to treat efficiency not as an optional element but as a design requirement. ASHRAE 90-1975, the first national energy standard in the US, formalized this shift and set a precedent for continuous code updates. This was an optimism achieved through governance: use less, gain more comfort, and make the system more resilient.

The recent pandemic has drawn attention to air, the most invisible building material. ASHRAE’s guidelines acknowledge the importance of airborne transmission and call for changes to ventilation and filtration systems to reduce the risk. Architects and engineers have responded to this call with cleaner air pathways, increased outdoor air exchange, and flexible spaces. Once again, disruptions have accelerated learning, and this learning is now quietly improving daily living spaces.

If the past has one message for the future, it is that optimism is a practice. We rebuild trust by prioritizing people, invent freely, and then organize with reality, preserving what our ancestors learned from the climate and allowing every crisis to sharpen our craft. The future of architecture is not a leap of faith; it is a rhythm: to experiment, adapt, and carry forward what works.

Current Challenges: Why Does Pessimism Persist in Architectural Discourse?

Climate Change and the Built Environment

The numbers alone can be discouraging: Buildings and construction account for approximately one-third of global energy consumption and approximately one-third of annual energy- and process-related CO₂ emissions. The problem is not only how we operate buildings, but also what we build them with—cement and steel together create a heavy carbon footprint. While efficiency is improving in some areas, the steady growth of the global building stock is outpacing these gains, meaning total emissions are slowly increasing. Climate policy is therefore now treating the built environment not as a side issue, but as a priority sector.

Designers feel caught between hotter summers, stricter regulations, and cost pressures. Heatwaves are pushing mechanical systems and networks to their limits; flood maps are redefining the meaning of “safe” land; and the supply chains for low-carbon materials are still immature. Nevertheless, we can see some actions as evidence of possibility. For example, the Brevik cement factory in Norway has begun capturing hundreds of thousands of tons of CO₂ annually, demonstrating how difficult-to-reduce materials can be redirected when policy, engineering, and finance align. The path is bumpy and expensive, but the message is not utopian, it is practical: the details of energy, materials, and regulations are now the domain of design.

Urban Inequality and the Housing Crisis

The housing problem is both a global and a personal issue. UN-Habitat estimates that approximately 2.8 billion people lack adequate housing, with over 1 billion of them living in informal settlements. This scale explains why housing discussions now carry the same importance on the agendas of municipalities and ministries as climate and public health: Housing shapes everything from commuting times to access to schools and resilience to disasters.

Affordable housing data clarifies the situation. Across the OECD, low-income renters in many countries spend more than 40% of their disposable income on housing costs, and official figures in the UK show that the average renter pays more than a third of their income in rent. When such a large portion of income is allocated to housing, families cut back on healthcare, education, and savings, and the city quietly hardens along income lines. Architects cannot solve wage stagnation or rent policy alone, but they design within these constraints every day.

There are viable solutions. Gradual and collaborative housing, serviced land, and modest financing have helped low-income households in many regions build safe and legal housing. Programs such as housing microfinance demonstrate that modest loans, provided with technical assistance, can significantly improve self-built homes and transform unsafe shelters into safer housing without requiring substantial subsidies. These tools do not replace public investments, but they offer architects and cities the opportunity to take immediate action while larger reforms progress slowly.

Excessive Commercialization and Design Homogenization

A common complaint is that new neighborhoods all feel the same: polished, branded, and strangely shallow. This criticism is not new: Edward Relph warned about “placelessness,” Marc Augé defined “placeless places” such as airports and shopping malls, and Rem Koolhaas subjected serial interiors to criticism in his book “Junkspace.” Their language reflects what many people feel on the ground: when finance, speed, and risk management dominate, buildings tend to repeat the safest forms and finishes.

Research on branding and urban design shows how global development models can suppress local fabric, material economies, and informal life. The result is not only visual uniformity but also social decay—spaces optimized for efficiency rather than a sense of belonging. You experience this in the calibrated wayfinding systems of a shopping mall or terminal that efficiently guides you while revealing very little about where you actually are. This friction between commercial efficiency and civic identity is why critics of homogenization continually return to issues of memory, craft, and public use.

The Decline of Public Infrastructure and Public Spaces

When basic infrastructure deteriorates, even good buildings cannot keep a city afloat. Engineers’ reports have been highlighting insufficient investment for years; in the United States, the national grade was C- in 2021, and journalists continue to emphasize that funding gaps persist despite recent spending. Globally, development banks note that there are still major deficiencies in essential systems such as transportation, water, and digital access that support daily life and economic activity. In parallel, UN-Habitat’s urban design guidelines remind cities to allocate nearly half of their land to streets and public spaces; where this fundamental rule is violated, public spaces diminish and private residential areas fill the void.

You can see the results in small but meaningful places. In New York City, audits of Privately Owned Public Spaces revealed that many sites failed to deliver the amenities and access promised in exchange for development incentives. When audits are delayed, the “public” aspect of these spaces erodes, and with it, confidence that density will deliver shared benefits. Reversing this erosion is not just a budget issue; it is also a matter of practice, management, and design that treats behaviors such as loitering, gathering, and protesting not as obligations but as civic rights.

Technological Dependency and the Loss of Craftsmanship

Digital tools and artificial intelligence are now accelerating drawing, coordination, and optimization processes. This represents real progress when projects are complex and timelines are tight. However, speed and ease can pull discipline toward safe defaults: the same detail families, the same facade logic, the same rendered atmospheres. Recent studies on artificial intelligence in architecture praise its efficiency, but also point to the risk of narrowing design exploration when outputs are trained according to a limited visual canon. The question is not whether to use the tools—of course we should—but how to keep curiosity and judgment in the loop.

On the other hand, many countries are facing a shortage of skilled workers, and this situation is quietly eroding the potential of buildings. US contractors estimate that the sector will need approximately half a million additional workers in 2024 and hundreds of thousands more in 2025. Forecasts in the UK similarly warn that this gap will continue. When young workers do not see a stable future on construction sites and educational opportunities are limited, the craft is lost. This loss is as much cultural as it is technical, because construction knowledge lives not only in manuals but also in the hands and teams of workers.

There are also promising examples. UNESCO’s interest in living crafts, from historic roofing work in Paris to traditional construction techniques elsewhere, demonstrates how policies can elevate the status of skilled artisans and attract new talent. If heritage crafts are recognized and fairly compensated, cities can retain the expertise needed to preserve and adapt their fabric. The lesson to be learned in a technology-driven age is clear: Digital speed should not replace enduring skills, but build upon them. Architecture improves when code libraries and detail libraries coexist.

Beacons of Hope: Contemporary Trends Pointing to a Brighter Future

Circular Design and the Reuse Revolution

The most promising change is treating “waste” not as an inevitable thing, but as a design flaw. Circular design requires architects to plan buildings as material banks with layers that can be maintained, modified, remanufactured, and ultimately recovered at high value. Analysts show that applying circular principles to cement, steel, aluminum, and plastics could reduce building emissions related to materials by more than a third by mid-century. This is proof that design choices can change the climate math in a positive direction.

Cities are beginning to incorporate circularity into their rules and tools. Amsterdam’s circular strategy combines policy with “material passports” that record a building’s contents and its value at the end of its life. This is a practical step toward component markets instead of landfill dumps. London planning now requires Full Life Cycle Carbon and Circular Economy Declarations for major projects and encourages clients to account for both visible and invisible emissions. These are not slogans; they are purchasing and permitting tools that make reuse and low-carbon design the easiest path.

Regulations implemented locally demonstrate the scale of circularity. Portland’s demolition rule saved approximately 2,000 tons of wood and countless fixtures from being discarded by dismantling approximately 600 homes instead of demolishing them, giving them a new life in other buildings. Local authorities documented how regulatory changes and training made this possible for small contractors. When circular design, policy, markets, and craftsmanship come together, it looks less like a trend and more like a new foundation.

Adaptive Reuse of Historic Buildings

Preserving and renovating a building is often the fastest way to reduce carbon emissions, as it avoids the large, upfront emissions associated with constructing a new structure. Conservation and climate groups repeatedly emphasize the same finding: Reuse delays or eliminates the carbon emissions associated with new construction, and timing is crucial as we race against time. For this reason, many cities and professional organizations now advocate for “renovation first” and treat new construction as exceptions that must be justified.

Policy and finance are also beginning to catch up with this reality. London’s Whole Life Cycle Carbon assessments and circular economy guide are increasingly promoting retention and renewal. In the US, federal agencies have created an interdepartmental toolkit to facilitate the conversion of offices into housing, and industry groups are finally seeing progress: dozens of projects completed in 2023, more in 2024, and hundreds planned or underway in 2025. However, analysts warn that only a portion of the buildings are truly feasible. The message is clear: Conversions won’t solve everything, but when design, debt, and zoning plans align, gains will be made in both climate and housing.

Beyond politics, high-profile projects are bringing this idea to life. High-profile redevelopment projects like Battersea Power Station demonstrate how industrial structures can accommodate new housing, cultural, and business opportunities while preserving the past. These projects remind us that cities can grow by adapting their historical assets to the needs of the future.

Community-Focused Design Initiatives

Residents shaping the outcomes also boosts optimism. The latest report by UN-Habitat on participatory programs documents that millions of people have been reached through jointly designed improvements and service enhancements. Academic studies on participatory budgeting, meanwhile, reveal measurable gains in civic trust and the resolution of urban problems. When communities decide how funds will be spent or how streets and squares will be developed, projects become more sustainable because they belong to the people who use them.

Community Land Trusts and cooperatives add a governance layer to this approach. London’s 2025 study shows that the sector is small but growing with the right support. Journalists and researchers note how CLTs keep housing permanently affordable while deepening residents’ control. As cities seek models that balance equity and resilience, CLTs transform neighbors from short-term beneficiaries into long-term stewards.

Even quick, tactical moves (closing streets to pedestrian traffic on weekends, temporary plazas, open street programs) are now backed by evidence. Research conducted from Barcelona to Japan and the US shows that interventions prioritizing pedestrians are linked to cleaner air, greater safety, and increased retail sales, while also highlighting the issues of equity and noise that need to be addressed in the next phase. Being community-focused does not mean being informal; it means being iterative, measured, and based on local priorities.

Urban planning models integrated with nature

Biophilic and water-sensitive plans are evolving from drafts into regulations. Europe’s new Nature Restoration Law sets binding restoration targets and compels member states to halt the loss of urban green spaces by 2030 and then increase shaded and green areas. Thus, parks, street trees, and green roofs will be transformed into infrastructure with legal support. This shift redefines shade, stormwater control, and biodiversity not as opportunities but as public services.

Cities are creating their own playbooks. Singapore’s “City in Nature” strategy links ecological corridors, pocket forests, and research programs to heat mitigation and daily access to green spaces. Draft master plans and institutional updates for 2025 show that efforts are expanding from policy to connected networks on the ground. In parallel, China’s sponge city program continues to expand permeable surfaces, wetlands, and storage areas to mitigate floods and droughts. Recent reviews catalog progress and challenges in applying standards across vastly different landscapes. Nature-first planning is not a single template; it is a toolbox that cities adapt to climate risks and social needs.

Results are becoming increasingly measurable at the neighborhood level. Assessments of Barcelona’s superblocks show a reduction in traffic and local decreases in NO₂ and particulate matter, as well as health benefits. This proves that incorporating green spaces and slow-traffic streets into the urban network can improve daily life while reducing air and noise pollution.

The Democratization of Artificial Intelligence, Parametric, and Design Tools

The most exciting aspect of today’s software ecosystem is how much of it is open or low-barrier. By leveraging certified engines like Ladybug Tools, Radiance, and EnergyPlus, it enables anyone with Rhino/Grasshopper to perform daylight, energy, airflow, and comfort analyses. Open-source BIM creation via BlenderBIM reduces costs for students and small firms while teaching IFC interoperability, and data hubs like Speckle enable models to be transferred between tools without file locking. These small technical freedoms enable broader participation.

At the same time, commercial platforms are incorporating early-stage analysis and automation into their conceptual design. For example, Autodesk Forma now integrates wind, solar, and noise data, enabling teams to perform mass and orientation tests before making decisions. The tight integration with Revit further accelerates this cycle. Feedback obtained during this early stage, where the cost of changes is low, helps smaller firms achieve performance targets that previously required specialized teams.

The adoption process is progressing unevenly, but progress is being made. According to AIA’s latest research, interest is high and pilot programs are becoming more widespread, but the number of companies fully implementing AI workflows is still in the minority. This may be good news: while reaping obvious benefits such as automated documentation, precedent search, and rapid scenario testing, time is being gained to establish norms such as fairness, authorship, and verification. Democratization is not just about access to tools; it is about shaping how these tools will empower the judiciary, not replace it.

Taken together, these glimmers of hope are not isolated trends, but a practical cycle of optimism. Cyclical methods reduce waste, reuse reduces carbon emissions, communities direct value, nature serves a dual purpose for climate and health, and better tools spread capabilities. The near future of architecture looks brighter because it is becoming more teachable, more measurable, and more shareable.

Projects That Embody Architectural Optimism

Lowline (New York): Underground Green Regeneration

Lowline envisioned something cities had scarcely attempted: a public park growing beneath the street. The core idea was deceptively simple: collect sunlight at the surface and transmit it downward via “remote light-harvesting” collectors, enabling plants to photosynthesize year-round. Initial prototypes proved physically feasible. In Manhattan’s Lower East Side neighborhood, a full-scale Lowline Lab was established beneath fiber-optic “heliotubes,” featuring lush greenery, ventilation, and controlled humidity. This was not merely a demonstration; it served as a testing ground to explore how light, air, and gardening could function within a long-abandoned space from the railway era.

The project finally came to a standstill in 2020 following disruptions in the funding process. This situation served as a stark reminder that visionary technologies must also withstand resilience tests in terms of finance and governance. However, it remains valuable as a case study: it charted a roadmap for revitalizing deep urban ruins with living systems, built public consensus around an impossible space, and left behind a refined toolkit (light direction, planting strategies, and public participation) that other cities can adapt for tunnels, courtyards, and basements seeking a second life. The optimism here isn’t about a ribbon-cutting ceremony; it’s about proving that a kind of urban surgery is possible and sharing the surgical notes.

Designing for Resilience (USA): Building Collaborative Resilience

After Hurricane Sandy, Rebuild by Design redefined disaster response as a public design process. HUD and its partners organized a multi-stage competition that brought together communities, scientists, engineers, and designers to examine risks and co-create solutions, rather than awarding projects behind closed doors. The result was not a single wall, but a portfolio of solutions tailored to each location: living shorelines, absorbent parks, wave barriers, pumps, and governance arrangements. This approach marked a true turning point: it shifted resilience from an engineering product to a civic project that incorporated research, pilot programs, and feedback.

You can see this approach taking shape. In Lower Manhattan, the Big U concept has evolved into the East Side Coastal Resiliency project, which is now opening in phases. This project combines the renewal of parks along the East River with flood protection measures. In New Jersey, the Hudson River “Resist, Delay, Store, Discharge” plan is actively under construction, combining green infrastructure with levees and gates to slow and hold rainwater in Hoboken and neighboring cities. These are no longer just drawings; they are contracts, construction fences, and new public spaces emerging from a design-focused framework that other coastal regions are beginning to replicate.

Ricardo Bofill’s La Fábrica: A Converted Cement Factory

La Fábrica is an example of optimism built from brick and concrete: a toxic, old cement factory has been transformed into a studio, home, and garden without erasing its traces. Bofill’s team selectively demolished, uncovered, and rebuilt, transforming silos into offices, a massive “cathedral” into an assembly and event space, and roofs into terraces surrounded by greenery. The building’s past is not hidden; industrial shells and romantic interiors coexist so that the space can simultaneously fulfill its function, inspire, and evoke the past.

Decades later, La Fábrica still hosts RBTA’s activities and serves as a guide for adaptable reuse on an architectural scale: preserve the elements that carry memory and structure, remove elements that block light and life, and gently add new systems. This resilience is important in the climate era, because every year it continues to serve as a studio and residence is a year in which embodied carbon is preserved, proving that cultural value and environmental awareness can be one and the same.

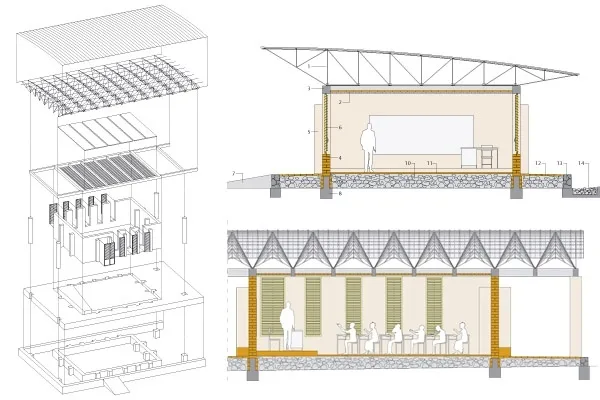

Gando Primary School (Burkina Faso): Strengthening the Local Language

Francis Kéré’s first project began with a question as simple as one a child might ask: How do you build a cool and bright classroom with almost no money? The answer was local earth, shade, and air. Compressed clay blocks, a wide-eaved canopy raised above the roof, and carefully placed openings created cross ventilation and a chimney effect that drew warm air out and cool air in. The construction was carried out together with the community, skills were passed on and celebrated, so that the school became not just a place of learning, but a way of learning by doing.

Recognition came quickly: In 2004, he won the Aga Khan Award, and this approach spread to teachers’ residences, libraries, and a middle school, all of which applied the same climate-friendly rules. Gando demonstrates that “high performance” does not require high technology, but rather design intelligence that harmonizes with materials, climate, and people. Thus, the building teaches comfort, dignity, and autonomy with every breeze that passes through it.

Visionary Thinkers: Voices Promoting Optimism in Their Fields

Diébédo Francis Kéré and the Power of Local Empowerment

Kéré’s work demonstrates that when design begins with people and climate, modest means can yield world-class architectural achievements. In his work beginning in his hometown of Gando, he used community labor, compacted earth, and a double-roof ventilation strategy to create bright, cool classrooms that honor daily life. The results reshaped the village’s boundaries of what was possible. This success came not because the buildings were expensive, but because they were smart: the Gando Primary School (completed in 2001) won the Aga Khan Award, and Kéré’s broader community-focused applications won the 2022 Pritzker Prize.

Public projects ranging from the Serpentine Pavilion in London to health and cultural buildings in West Africa share the same idea: a collective architecture that creates beauty and durability through local materials, climate knowledge, and collaborative production. These works chart a replicable roadmap for regions with limited budgets and challenging climatic conditions: build with the materials at hand, teach the method as you build, and derive comfort from air, shade, and proportion before turning to machines.

Carlo Ratti and the Integration of Technology and Ecology

Ratti’s contribution is to treat cities as living systems that can perceive and respond. Through MIT’s Senseable City Lab and his own application CRA, he has demonstrated how data and prototypes can transform behaviors and policies into cleaner, more friendly urban environments, such as tracking waste flows, turning bicycles into mobile sensors, or shading public spaces with responsive canopies. What matters is not the gadgets, but the feedback: when citizens see how systems work, they can change them.

As curator of the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale, he argued that reduction alone is no longer sufficient and that architecture must embrace harmony. To live well in a changing climate, nature, technology, and collective action must be brought together. His proposal for Helsinki, “Hot Heart,” which won the city’s energy competition, embodies this approach by storing renewable heat on an archipelago that also serves as a public landscape. This creates a template that combines infrastructure with place-making, making the green transition a tangible and shared experience.

Kate Orff and Resilient Ecological Urbanism

Orff’s work reintegrates ecology into urban life, transforming resilience into something you can walk through, learn about, and love. His company SCAPE’s Living Breakwaters project surrounds Staten Island with coastal structures that reduce wave energy, create habitats, and support community programs through a planned Water Center. This nature-based infrastructure is now fully constructed. The MacArthur Fellowship award he received in 2017 recognized this activist and science-focused approach to public spaces.

Beyond individual projects, Orff created “Towards Urban Ecology,” a vocabulary and guidebook for designers and officials seeking mutual benefits: flood protection systems that teach marine ecology, coastlines that foster environmental awareness, and park systems that cool neighborhoods while restoring biodiversity. This is an optimism measured not by slogans, but by oysters, students, and summer shade.

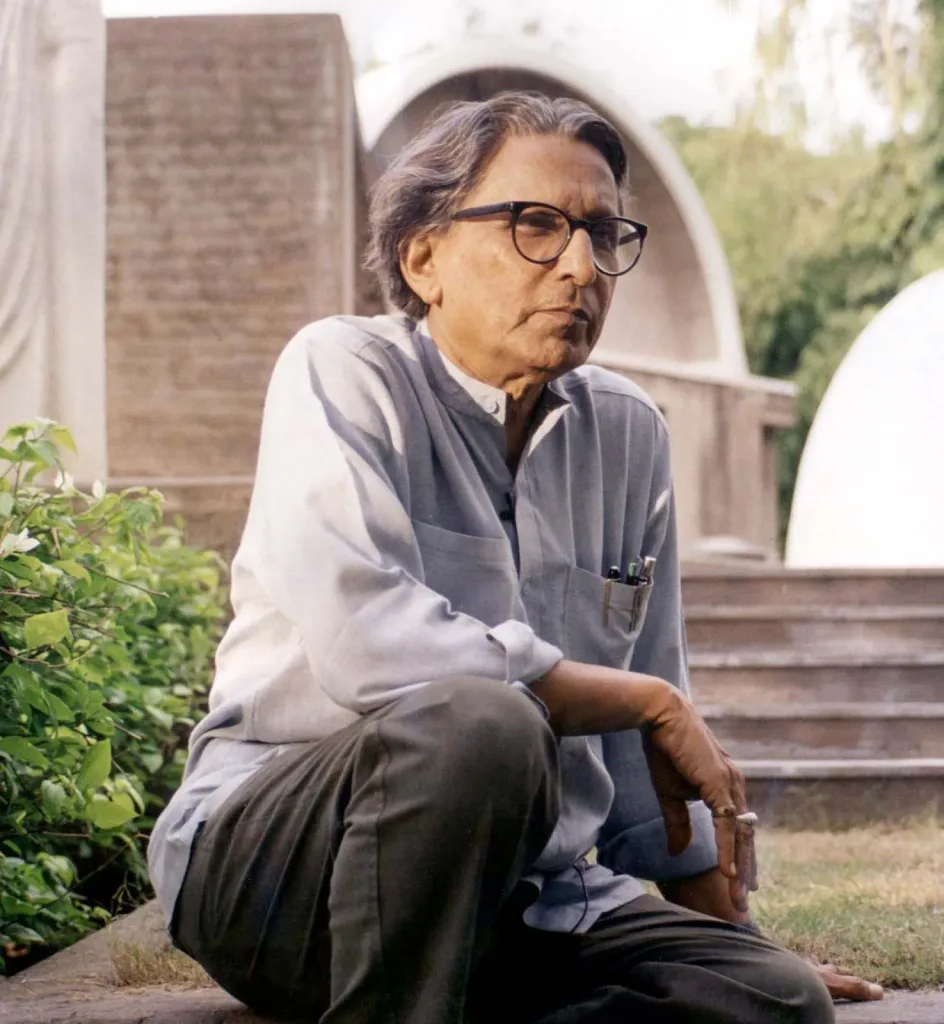

Balkrishna Doshi and Architecture as a Human Right

Doshi spent decades proving that dignity could be designed on a large scale. His landmark residential project Aranya in Indore organized tens of thousands of people into walkable clusters equipped with service centers and courtyards, enabling families to build and expand their homes according to their means. This is a town that grows with its residents, not against them. This is one of the reasons the Pritzker Committee honored Doshi in 2018 for his architecture that “impacts humanity” with grace and depth.

His legacy extends from educational institutions to small homes, always adapting to climate and culture, and emphasizing that affordability does not equate to simplicity. Even after his passing in 2023, his work continues to guide a generation toward a simple standard: A design is not complete unless it enhances people’s sense of life, learning, and belonging.

Building a Future Worth Believing In

Reframing Architectural Success Beyond Aesthetics

The definition of “good” architecture that will remain valid in the future begins with how buildings perform for people and the planet after their opening ceremony. This is why usage performance ratings such as NABERS UK are important: these ratings grade offices based on measured annual energy consumption rather than design promises, and translate the results into a public metric that customers and building occupants can understand and improve upon. When a building’s energy profile is visible, success becomes a living target rather than a static certificate.

This perspective also extends to carbon and health. London now requires large projects to provide full life-cycle carbon assessments. This allows teams to account not only for emissions visible on electricity bills, but also for emissions arising from materials, construction, operation, and end-of-life processes. Post-occupancy approaches such as Soft Landings and structured POE complete the cycle by fine-tuning systems with users, using measured comfort, noise, and energy data. These components reinforce each other: Standards like PAS 2080 guide whole-life carbon management, city guidelines demand transparent calculations, and assessment frameworks incorporate learning into practice. Success, when redefined, emerges as a building that proves its claims in use and improves with each season.

Educating Future Generations with Optimism and Purpose

When education links design to the public good, optimism becomes teachable. The UNESCO-UIA Charter defines the architect as a general specialist and sometimes as a “facilitator” who brings others together. This definition legitimizes climate-informed practices as fundamental rather than marginal, under community leadership. When combined with national roadmaps such as the RIBA/ARB system in the United Kingdom, it sets the expectation that technical competence, ethics, and service are integrated.

This ethos extends to schools and even K-12. AIA’s K-12 initiatives develop hands-on curricula, tours, and internship guides that make design accessible to young people, especially those outside the traditional education system. When students see architecture as a tool for health, climate, and equity, they enter studios with better questions. Biennial platforms are amplifying this educational shift: Lesley Lokko’s “Laboratory of the Future” focuses on new voices and geographies, while Carlo Ratti’s 2025 edition argues that adaptation will require the collaboration of natural, artificial, and collective intelligence. These mainstream stages teach the public and the profession that change is both possible and necessary.

Promoting Policies That Enable Inclusive Design

Inclusivity increases when rules make it the default. The Americans with Disabilities Act establishes applicable design standards for public, commercial, and state/local government facilities, detailing everything from pathways and doors to communication features. Internationally, ISO 21542:2021 brings together best practice requirements for accessibility and usability in access, circulation, and egress, providing a common reference that designers and authorities can adopt. These frameworks are the quiet architecture of respectability: they normalize bodily, sensory, and cognitive diversity.

Cities can go even further by linking inclusivity to planning permission. London Planning Policy D5 treats inclusive design as an integral part of good design and provides guidelines ranging from evacuation strategies to design and access statements. If planning conditions and building control mirror each other, inclusivity is not an additional element but part of the process from concept draft to delivery.

Combining Global Traditions with Modern Innovation

A hopeful future often begins with improving the past. Adaptable mashrabiya systems used in projects like Al Bahar Towers demonstrate how a centuries-old shading concept can be transformed into a sensitive facade that reduces sunlight while preserving local identity. In parallel, research on wind catchers and courtyards numerically confirms a fact already known to local builders: openings, chimneys, and shaded voids of the right dimensions provide ventilation and cooler interiors in hot regions, reducing dependence on mechanical systems at critical moments. The bridge is a methodological approach (measurement, simulation, and iteration), while the inspiration comes from culture.

Craftsmanship is also part of this bridge. UNESCO’s recognition of Paris’s zinc roof craftsmen highlights that living skills form the foundation; when these skills are valued, cities can preserve and adapt their heritage to a high standard. Combine these crafts with contemporary performance targets, from Passive House thermal demand limitations to local climate modeling, and tradition ceases to be an obstacle to progress and instead becomes a catalyst for sensitivity.

Writing, Speaking, and Sharing: Architects as Public Intellectuals

If architects explain the “reasons” behind their decisions in simple terms, public trust increases. Jane Jacobs did not win with her drawings; she won with her books, articles, and testimonies that linked street life to political choices and turned neighbors into a movement. Today’s equivalent examples range from city-focused toolkits to open-source details and exhibitions that prioritize harmony and equality. When practitioners publish the lessons they have learned, open their data, and remain open to criticism, they transform their projects into civic education.

This role is broader than advocacy; it is about managing attention. After a decade of noise (both literally and figuratively), health organizations such as the WHO are linking environmental noise to cardiovascular and mental health problems. When architects translate this evidence into room acoustics, street sections, and purchase summaries, they demonstrate a public benefit professionalism that gains authority through its usefulness. Optimism becomes credible when the field showcases its work, shares its resources, and involves the public in design discussions.