In architecture, a door is never merely a hole in a wall. It is a boundary zone charged with symbolism and emotional resonance—what Gaston Bachelard called “the entire cosmos of the half-open,” a source of dreams and allure. Throughout cultures and eras, doorways have been carefully shaped to reflect values, facilitate transitions, and guide human experience. This article examines five thematic “thresholds,” from sacred doors to modern glass facades, revealing how each form of entrance conveys meanings about space and society. We begin with cultural symbolism, then move through power and defense, climate adaptation, and social choreography, finally asking what remains of the door in the age of transparency. Ultimately, we return to consider reclaiming the doorway as a space of encounter.

What Cultural Values Are Encoded in the Form of the Doorway?

Doors typically function as identity and belief thresholds, not only separating the inside from the outside, but also defining the values of the world within. Consider the modest Japanese genkan—the recessed entrance hall of traditional homes. The genkan is a place where one can remove their shoes and mentally shake off the dust of the outside world; it “marks the boundary between a Japanese home and the outside world.” The physical form of the genkan codes purity and respect: a step ( agari-kamachi) clearly separates the outside from the inside, keeping dirt out and symbolically elevating the sanctity of the home. According to Japanese tradition, even casual visitors can be greeted and conversed with in the genkan without being invited fully inside—a subtle social threshold that offers hospitality while preserving privacy. The modest design of the genkan thus reflects an almost ritualistic sense of transition from the mundane to the pure, similar to the torii gates of Shinto shrines, which signify humility, cleanliness, and entry into sacred spaces.

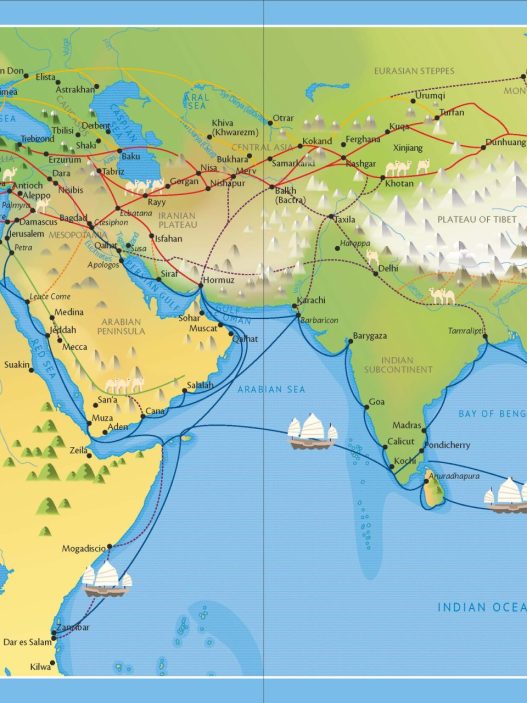

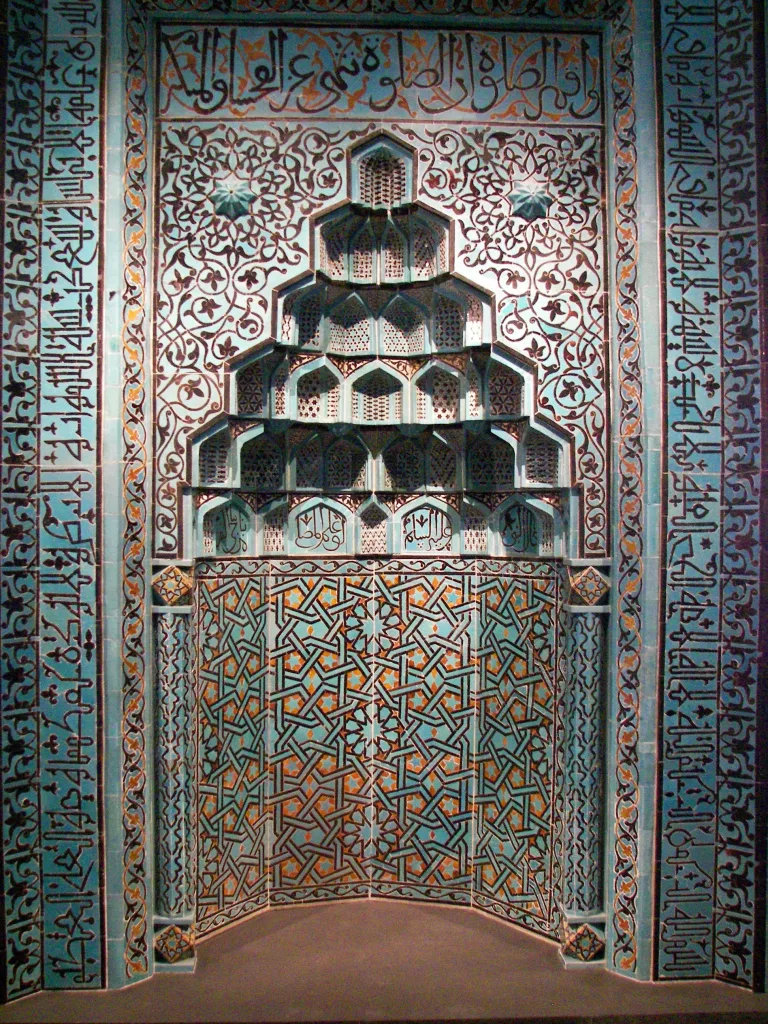

In contrast, many South Asian and Islamic cultures have historically adorned doorways with larger symbolic decorations to express spiritual transition. India’s independent toranas—ornate arched gates at temple entrances—are an example of this. In the Hindu-Buddhist tradition, toranas “bring good luck and symbolize auspicious and festive days,” heralding a person’s entry into a sacred or noble realm. Carved lintels often depict protective deities or auspicious creatures (such as the makara sea creature motif on temple doors), visually conveying that passing under this arch is an act of leaving the mundane behind. Similarly, the use of mukarnas (honeycomb or hanging vault) above doors in Islamic architecture elevates doorways to cosmic symbolism. A muqarnas entrance is not merely decorative but metaphysical: historically, “muqarnas domes were often built over entrance doors to form a threshold between two worlds” and have a celestial connotation representing the transition from the earthly realm to a sacred one. The intricate geometry at the top invites visitors to look up—a moment of pause and wonder—reinforcing the sense of entering a space with a higher order or divine presence.

Cultural expressions of transition: On the left, the wooden entrance (genkan) of a Japanese house emphasizes simplicity, and a raised threshold where shoes are removed embodies humility and purity. On the right, a monumental caravanserai door with a mukarnas vault in Turkey emphasizes grandeur—the layered crown above the door symbolizes the passage to a sacred or protected area.

Indeed, thresholds between cultures often encode ritual expectations. In parts of the Middle East and South Asia, thresholds may be honored with small offerings or symbols—consider the words spoken when stepping over a house’s threshold, or a rangoli pattern or hanging garland placed to bless those entering. In West Africa, carved figures on Dogon granary doors traditionally protect the harvest and depict ancestors who guard the threshold. Whether modest or elaborate, these design choices convey a great deal: a door can declare who it belongs to (those inside and those outside), enforce codes of purity (clean and unclean), and dramatize the act of transitioning from one realm or state of being to another.

The shape and decoration of a door serve as a cultural text. Bending down or removing one’s shoes (as with a low Japanese or Indian door), feeling reverence (passing under a lofty arch or a muqarnas vault), or entering a protected, privileged space all indicate this.

How Do Door Proportions and Decorations Reflect Power and Protection?

Beyond symbolism, the scale and structure of doorways have long been used to express power dynamics—who is in control and who is vulnerable once the threshold is crossed. In fortifications and palaces, a majestic doorway telegraphs authority while also providing literal fortification against threats. For example, the sturdy doors of medieval European castles were as much defensive machines as they were architectural statements. Castles typically limited themselves to a single main gate (“passages… were considered weak points,” so architects “severely restricted the number of openings” in the walls). The main entrance was deeply embedded within thick walls, creating a menacing threshold—a dark passage where defenders could trap intruders between a heavy wooden door and a rising portcullis grille. Doors were typically made “as thick as possible, usually with layers of wood” and reinforced with iron studs or plates. Such a door speaks less of pleasure than of severity: its proportions (small relative to the massive wall) and features (nails, drawbridges, murder holes at the top) send a clear message that crossing this threshold without permission is dangerous. Essentially, the narrow fortified gate reveals a hierarchy of power—allowing rulers and allies to enter while keeping enemies out by its sheer physical form.

In contrast, some monumental gates project power through grandeur and splendor rather than overt militancy. The gates of ancient empires—such as the soaring stone portals of the Inca and Maya civilizations—were designed to both impress and endure. Inca gates, in particular, have a distinctive trapezoidal shape (wider at the base, tapering upwards) that is not only aesthetically pleasing with its sloping walls, but also structurally sound in terms of earthquake resistance. At Machu Picchu and elsewhere, “doors and windows are trapezoidal in shape, helping to absorb seismic shock.” This form expresses a civilization’s mastery over nature: Inca rulers could ensure the stability of their temples by literally shaping the thresholds of buildings to withstand the shaking ground. At the same time, passing through a trapezoidal stone doorway, often finely fitted without mortar, conveys permanence and mastery. Even without overt ornamentation, the sheer solidity and perfect carving of an Inca gateway radiates authority. One senses that the space beyond has been sanctioned by great engineers and, therefore, by great power. Similarly, consider the great palace gates of Mughal India or imperial China: Their monumental scale (sometimes several stories high) and layered entrance courtyards expressed hierarchy—commoners could only pass through the outer gate, while smaller inner gates for higher-status entrances created a spatial power hierarchy.

Door design is balanced to serve the authority described by Vitruvius as firmitas and venustas—sturdiness and beauty. While a castle entrance emphasizes firmness (thick, buttressed, defensible), a ceremonial city gate emphasizes beauty (lofty, ornate, awe-inspiring). Yet both types protect and proclaim. Consider the depth of the threshold in many historical passageways: from the barbican of a European castle to the winding entrance halls of an Ottoman castle, a deep entrance passageway forces a psychological pause and provides multiple layers of security. For example, the entrance to a medieval Arab castle in Doha was so deep that it contained adjoining guard rooms within the passageway, providing “additional surveillance and protection” before fully entering the compound. The threshold became a power antechamber where visitors could be scrutinized or forced to dismount—a spatial assertion that you proceeded on the sovereign’s terms. In more peaceful contexts, this layered entrance also allowed for pomp and ceremony (processions slowing down under the arches, etc.).

Even on a civilian scale, gates spread protection and hierarchy. City gates were often doubled as symbols of civic pride and control—adorned with coats of arms, ramparts, or victory inscriptions to proclaim sovereign power. Passing through these gates meant both an honor and submission to the law. Therefore, whether they were massive gates (the iron-studded gates of a walled city) or monumental heights (the 30-meter Buland Darwaza gate built by the Mughal Emperor Akbar), or sophisticated engineering (Inca trapezoidal portals angled to resist the encroachment of nature), gate styles reflect a continuity of power: “invitation and barrier ” combined. They invite the obedient with splendor and block the enemy with a harsh rigidity. The interplay of proportion and ornamentation at these thresholds is not accidental—it is a calculated message about who holds the keys and the power of the space beyond the gate.

How Do Door Styles Adapt to Climate and Material Restrictions?

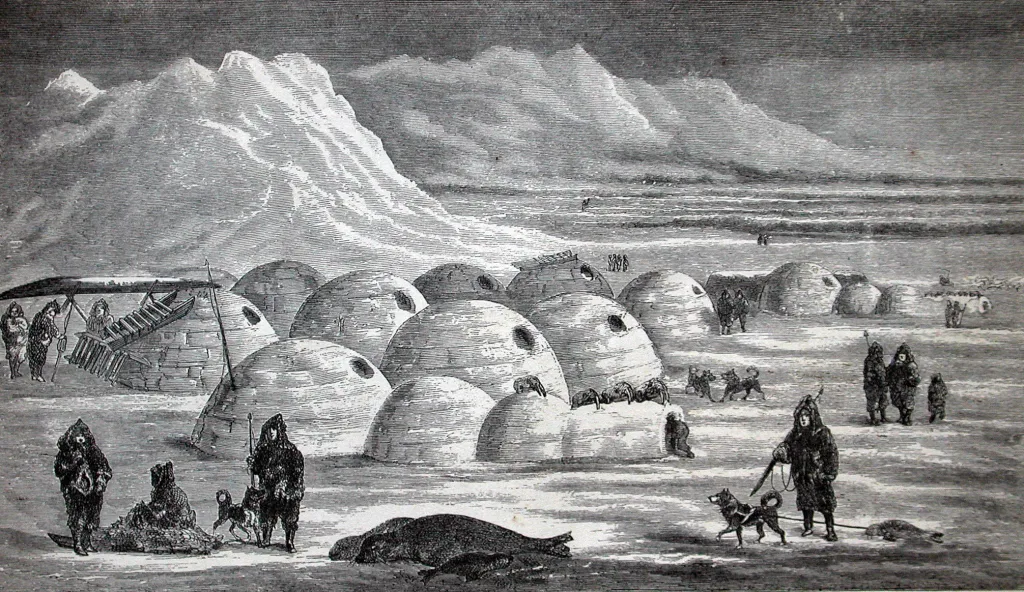

The design of thresholds is also greatly influenced by the environment. Around the world, local doors have evolved in response to climatic realities and available materials, becoming skillful mediators between interior and exterior spaces. In extreme climates, the door often acts as a buffer against weather conditions—essentially an architectural microclimate. Consider the example of an Inuit igloo at the North Pole: the entrance is typically a small tunnel or a low opening below the main living level. This traps cold air in the tunnel while allowing warmer air to remain in the elevated interior—a clever thermal stratification. The tunnel also blocks icy winds; as one source explains, an igloo entrance usually has “at least one steeply angled tunnel section that must be crawled through, [so] freezing winds cannot blow directly into the living area.” Here, the door is literally a thermal lock and sacrifices convenience (one must crouch and crawl) for survival. Its shape (small, insulated with snow) takes advantage of the low thermal conductivity of compressed snow and air to keep the interior 70°F warmer than the outside. In short, the climate speaks through this threshold: a larger or steeper door would be deadly in -50°F winds, so cultural practice and door design converged on a narrow, sheltered entrance.

In the hot and arid Sahel region of West Africa, the Dogon and others’ earthen dwellings employ different strategies. Thick mud-brick walls (adobe) have high thermal mass and low conductivity, slowly absorbing heat to keep interiors cool. Doors in these settlements tend to be small and recessed. A low door not only provides shade for the entrance and minimizes the sun’s penetration, but also forces people to bend down, inadvertently reducing the flow of hot air from outside with each entry. The work of climate control is done by materials and proportions: the mud plaster around the door cools the incoming air, and the door itself, usually made of wood, remains small to limit heat exchange. In Dogon grain stores, a small door also protects the stored grain from hot winds and pests. These practical arrangements become cultural norms: a small, low door is seen as a sign of respect (you bow to enter) and caution. Similarly, many local architectures in extremely hot regions feature an intermediate entry porch or entry hall to buffer the transition. For example, Arab and Swahili houses often have a covered porch(liwan or baraza) where one can sit in the shade at the threshold, which also provides social adaptation to the climate—the porch filters direct sunlight while the door can remain open for ventilation.

Regional variations in overhead protection at door entrances also reflect local climate logic. In monsoon and tropical regions, deep eaves or verandas protect door entrances from rain and harsh sunlight. A classic example is the Chinese courtyard house: the entrance door is usually covered by a prominent eave or canopy, part of a roof system with generous overhangs to direct rainwater and provide shade. The entrance usually faces south (in northern China) to catch the winter sun, but there is an immediate screen wall inside to block cold winds and evil spirits—a clever blend of cosmology and climate-adaptive planning. In Ottoman Turkish neighborhoods, homes in warmer regions often featured a semi-open front gallery or portico. This columned porch at the entrance (hayat or sofa) served as a shaded outdoor room, keeping out the summer sun and creating a cool buffer area for receiving visitors. In the Anatolian plateau, traditional houses usually featured an outer sofa—essentially a covered terrace at the front door—and this sofa was oriented to capture prevailing breezes while shading the interior. Therefore, the door entrance is not an opening in line with the facade, but is recessed behind this open sofa, allowing airflow and dispersing the temperature gradient between outside and inside.

The choice of threshold material is also important. For example, wood has low thermal conductivity, so wooden doors or frames can reduce thermal bridging compared to metal. Stone thresholds, common in older masonry buildings, provide durability but can be heat-absorbing or cold bridges. In some Iranian and Indian architectures, you may even find double-layered entrance doors (an outer metal door and an inner wooden door), one for security and the other for insulation, depending on the time of day. Local builders have intuitively balanced these factors. In mudbrick architecture, a raised threshold or step at the door keeps floodwaters and pests out, and because mud is vulnerable to erosion in openings, wooden thresholds or stone foundations are added, demonstrating the interaction of materials for longevity. Even in temperate Europe, local houses typically had thick oak doors set deep into stone walls, sometimes with a second inner door (vestibule) to buffer the winter cold—the precursor to today’s vestibules or storm doors.

Door styles around the world are masterfully adapted to the climate through their design. Some create true thermal entrances (igloo tunnels, mud porches), while others rely on geometry (small size, trapezoidal stability) or material layers to respond to local conditions. An old proverb says “the door is the mouth of the house”; environmentally, this “mouth” can be opened wide or narrowed to regulate the house’s breath. The Dogon, the Inuit, the Chinese—each has shaped the threshold as the first line of defense against nature’s challenges and turned the door into a passive performance element. Today, we can learn from these solutions: incorporating shaded transition areas, air locks, and earth-integrated designs into entrances to naturally cool and heat our buildings. Climate speaks through clay, stone, and wood—and nowhere does it speak more than at the threshold where the outside meets the inside.

How Does the Spatial Logic of a Door Direct Movement and Social Behavior?

Whether it’s a house, a temple, or a city, the choreography of entering a space has profound social implications. Door design is often about controlling what you experience and how you behave as you pass through. Culturally, this can provide privacy, create a sequential ritual, or direct a person’s gaze and footsteps in meaningful ways.

In many Islamic and Middle Eastern traditions, doors are deliberately designed to hide private life from direct view. For example, the entrance to a traditional Gulf Arab house or a majlis (guest reception room) is usually not a straight shot into the living areas, but a curved or angled passageway. One common design is a small foyer where the visitor turns one or two corners before reaching the central courtyard or guest room. This “zigzag” entry sequence prevents outsiders from seeing directly inside (protecting the family, especially women, from unwanted glances). It also allows the residents to properly observe and greet the visitor (perhaps from behind a screen) before fully accepting them. In the homes of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates of the past, the front door opened onto a walled entrance courtyard or a corridor with a dikka (bench) where guests waited, creating a spatial pause that demanded courtesy and humility. Social logic is embedded within the threshold: movement is slowed and lines of sight are filtered to ensure that privacy and hospitality work hand in hand.

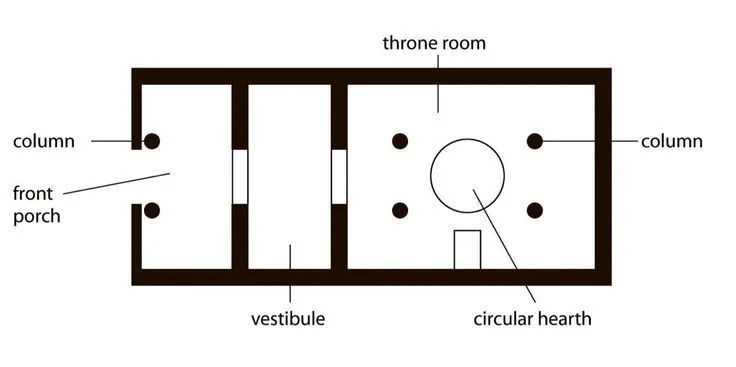

Compare this to the ancient Greek megaron layout. The megaron, the great hall of Mycenaean palaces, had a very axial door logic: one entered through a front porch aligned with the central hearth and (in some cases) the throne at the back of the hall. This straight alignment (door → hearth → throne) meant that as soon as the doors opened, the person’s view and path were powerfully directed towards the center of power (the fire and the ruler’s seat, symbolizing the household or the state). The effect is ceremonial and hierarchical—an entering subject follows an almost ritualistic path of direct approach to the presence of authority. There is no concealment or winding; instead, there is a clear visibility and symmetry emphasizing order and dominance. Even in classical temples derived from the megaron concept, the door is centered and often taller than human scale, immediately directing the entrant’s movement and gaze toward the cult statue. The social message is the transparency of hierarchy: nothing is accidental; you must focus on the important element beyond the threshold and perhaps approach it with reverence.

Between these extremes, many local architectures modulate door entrances to achieve a social inclination. Traditional Turkish and Balkan houses are a good example of this: a visitor entering from the street typically first steps into an outer hall or foyer—a semi-public space where strangers or acquaintances can be received without entering the depths of the house. Separate doors lead from this foyer to the private family rooms. Thus, the front door opens not directly onto privacy, but onto a space that serves as an agent of social screening. The spatial logic guides the person’s movement towards a neutral zone (usually furnished for sitting and hospitality). Only trusted individuals or family members proceed further inward, perhaps through another door into a private room. This layered entry reflects the social norm of gradual privacy: one’s behavior adjusts at each threshold (formal on the divan, relaxed in the private room). In many rural Anatolian homes, the front hayat (open porch) or eyvan effectively serves as a hospitality lounge—here you can share tea with a neighbor, but you do not invite them inside. Thus, the architecture, through the progression of doorways, challenges the boundaries of interaction.

We also see spatial choreography in religious architecture: ornate doorways are used to create anticipation or a sense of sanctity. A classic example is zigzagging into the prayer hall of an Islamic mosque—one usually enters through a courtyard, then passes through an indirect entrance to the mosque (sometimes there is a veiled foyer), so that one’s orientation is properly aligned and one symbolically leaves the worldly behind. In Iranian mosques, the entrance gate (eyvan) may be at right angles to the main prayer hall axis, requiring a turn that metaphorically prepares the worshipper for a new focus. Similarly, in Hindu temples, multiple inward-opening door thresholds (gopurams or gate towers) are used, each framing a more restricted space; thus, movement becomes a ritual of transition from the external worldly life to the inner spiritual core.

Screens, curves, and aligned landscapes are the tools of this choreography. A beautiful example: in a traditional Japanese tea house, a small crawl-through door (nijiri-guchi) is used, forcing samurai or peasants to bow and leave their swords behind, equalizing them in humility for the tea ceremony. Here, the small size of the door and its low threshold, by design, directs behaviors (crawling, disarming) and mental states (humility) directly. In everyday terms, even something as simple as the Dutch door (horizontally divided) in farmhouses allows communication and exchange (the upper half open for conversation) while keeping animals or small children inside/outside (the lower half closed). The social function (friendly exchange with a degree of control) is embedded in the form of the door.

The spatial logic of a door—whether straight or angled, direct or layered—regulates how we enter and how we relate to others once inside. Linear thresholds (like a megaron) tend to emphasize visibility and power and create a direct stage for encounter. Offset or layered thresholds, on the other hand, tend to emphasize privacy, contemplation, and gradual participation and allow the person to adapt as they move from boundary to boundary. Neither is inherently better; each serves social needs. As one architectural work notes, threshold areas “support various activities by providing shelter, defining boundaries, and enhancing community interaction and security.” A well-designed series of doors can make a space more inviting (by offering an intimate transition zone) or more imposing (by framing what lies beyond in a grand manner). It can choreograph etiquette—we naturally slow down in a narrow entrance or pause under an ornate arch—and thus attune our mindset to what a culture expects at that threshold (respect, readiness to socialize, or deference to authority). Nothing in architecture choreographs movement like a doorway.

In the Age of Glass Facades and Seamless Access, What Will Happen to Door Entrances?

Modern design and technology have seemingly pushed the concept of doors in two opposite directions: maximum transparency (dissolving the threshold) and maximum control (securing the threshold). Both trends raise the question: Are we losing the rich spatial and cultural role of doors?

On the one hand, contemporary architecture generally strives to provide continuity between interior and exterior spaces. The proliferation of glass facades, curtain walls, and automatic sliding doors in commercial buildings has rendered the traditional door entrance nearly invisible. When you walk into a modern office tower or shopping mall, you may enter through a wide revolving door or a sensor-activated sliding glass panel that barely interrupts your stride. The threshold experience is frictionless—no step, no pause, sometimes not even a change in material underfoot. This design philosophy stems partly from the Modernist transparency and openness ethos: the boundary between public street and private interior is minimized to invite people in and project an image of accessibility. For example, Apple’s flagship stores feature massive glass walls and frameless entrances—just open air controlled by thin glass doors. At Apple Fifth Avenue in New York, the entrance consists of a 32-foot glass cube that creates a “landing ceremony” but is not actually an opaque door.

The aim was to “elevate” visitors with a grand but barrier-free entrance—a pure invitation. In many such designs, the door is “lost” on the façade, often reduced to a sensor-operated door that people may not even notice (which sometimes leads to unfortunate incidents such as people bumping into glass walls).

This continuity offers convenience and symbolic transparency (for example, the democracy of a library’s open atrium entrance or a store’s consumer-friendly reception), while also eliminating the sense of ceremony and threshold developed by older buildings. There is very little transition or emotional momentum—you are simply inside. As architect Juhani Pallasmaa points out, the erosion of thresholds in modernity can deprive us of the psychological preparation and sense of arrival provided by traditional thresholds. In the past, a door would slow us down, perhaps demanding a tactile interaction (turning a knob, knocking on wood) that mentally shifted our state. Now, however, the whirring of an automatic door is barely noticeable; we pass through while remaining in the same frame of mind. The result can be a kind of placelessness—one shopping mall or airport resembles another because their entrances are not culturally specific gateways, but generic glass rectangles.

On the other hand, security technology has raised the bar in less visible ways. Consider keycard access, intercom entries, metal detectors—the door is still there, but it may just be a plain glass panel that opens only if you have the right credentials. The ritual of greeting at the door is being replaced by badge swiping or facial recognition. In corporate offices, the trend toward large glass lobbies with security turnstiles signifies the symbolic door being pushed deeper into technology-controlled areas. This controversially reinforces privilege: outsiders physically see inside these transparent fortresses but cannot enter without permission. The social signal is paradoxical—apparent openness, actual closure. A “badge-only” glass door declares that security and efficiency trump hospitality; it is a threshold of control, not ceremony. In public architecture too, increased security (especially post-9/11) has led to the redesign of entrances: multi-scan doors, barriers at entrances, entrance foyers as bottlenecks. Even if architecture aestheticizes seamless entry, reality often imposes new layers (airport check-in is a passageway of invisible thresholds, each marked by a security guard or scanner rather than an ornate door). One might ask what these new thresholds signify socially. Perhaps a lack of trust, a prioritization of surveillance. They certainly do not celebrate arrival as an old city gate or a porch once did.

In response, contemporary architects have adopted various approaches to reinterpret the threshold. Some, like Peter Zumthor, consciously design entrances that restore a sense of depth and materiality. For example, Zumthor’s Kolumba Museum in Cologne integrates the city’s ruins and uses a subtle, recessed entrance—visitors pass through a heavy, monolithic door embedded in a brick curtain, leaving the bright street for a dim passageway, then emerging back into light inside. This plays on the sequence of old church entrances and transforms the act of entering into a reflective moment. Other modern designs attempt the threshold as a transition in light and texture—for example, a library might feature a compressed, dark entrance porch that suddenly opens onto a long, sunlit lobby, creating a dramatic sense of “transition.” These gestures echo the spatial poetry of older thresholds, but are translated into modern forms.

Meanwhile, some commercial architecture fully embraces the spectacle at the threshold—glass entrances, massive sliding doors—to the extent that the door itself becomes a brand element (Apple’s cube or large doors that merge indoor and outdoor café seating areas). In these cases, we are reclaiming a kind of ceremony: the theatrical swing of a large glass door, the blending of a fountain plaza with the interior of a store, etc., can be unforgettable. However, this is a different kind of ritual and usually focuses on consumption and visual continuity rather than cultural meaning.

Sociologically, the following concern may arise: If everywhere becomes an “open plan,” will we lose the cultural signals of the entrance? Already, in homes, the traditional entrance hall or front porch has diminished in many designs—garages and open-plan living mean a person can enter directly into a kitchen or living area. The flattening of thresholds may be related to the flattening of boundaries between public and private life. Some academics even suggest that the absence of clear entry transitions can make spaces feel less intimate or emotionally cold, because the subtle cues that say “you’re safe inside now” or “prepare to go outside” are diminished.

A secure, glass building with ID card access may not have a visible threshold, but it has a significant impact on codes and circuits. This raises the question: can we give new meaning to modern thresholds? Perhaps through art (wall paintings or signs at entrances), through architectural form (creating entrances that also serve as community exhibition or seating areas), or through smart technology that personalizes the entrance (a lighting change or sound that signals your arrival).

The ethical dimension is also of key importance: A transparent corporate tower with a secret selective door gives off signals of privilege while pretending to be democratic. This can undermine social trust. Compare this to a courthouse with stately staircases and porticos—you know where you stand at this threshold; it invites respect for the law. Today’s courthouses, with airport-level security screening at their doors, convey something colder: suspicion and bureaucracy.

The challenge facing contemporary design is reconciling our desire for openness and security with people’s need for meaningful spatial transitions. A glass facade does not automatically provide a welcoming feeling simply because it is open—it can often feel impersonal. We see some responses: biophilic entries (adding greenery, water, or natural materials to the door entrance) to soften the transition, or designing threshold plazas (semi-public spaces before entering a building) to compensate for the lost porch or landing. The best new buildings create a threshold in spirit, if not with an actual door—a change in flooring material, a drop in the ceiling, a framing device—something that says, “You are now entering a different world.”

Ultimately, in the age of uninterrupted access, the door faces the risk of becoming invisible but more controlling—an irony of our time. Yet we pass through these imaginary doors that follow us. By losing the tangible threshold, we may also be losing the pause for thought or the conscious respect we feel when entering someone’s space. As the question implies, the diminishing presence of thresholds also means a decline in the rituals of greeting, parting, and self-direction.

Reclaiming the Doorway as a Meeting Place

Throughout these five thematic studies, a common theme emerges: doors are rich interfaces between worlds—not just physical worlds (inside/outside), but also between states of being, social roles, and values. They have been places of arrival, hesitation, identity, and encounter. A Japanese genkan, a castle gate, a mud-brick porch, a zigzag foyer—each uniquely stages the moment of transition, giving it meaning. In many languages, the word threshold also means beginning or moment of truth (think of the expression “crossing the threshold” meaning reaching a new stage). This is no coincidence; spatial thresholds have always reflected life thresholds.

As we have observed, traditional cultures have approached the threshold with respect—as a place of slowing down and accepting change. Whether it was removing shoes, adjusting clothing, praying, or simply knocking and waiting, the rituals surrounding doors created a buffer that helped people transition emotionally and socially. In architecture, these rituals were supported by concrete designs: steps, courtyards, lintels to bow under, doors that physically opened. In modern life, most of these pauses have been eliminated in favor of speed and convenience. Still, it’s worth asking: at what cost? When a person enters a building from the street and reaches their desk without even a door to mark the transition, are we losing something of the awareness of place?

Architectural historian Arnold Hauser once noted that a door is both an opening and an obstacle, and that its poetic quality lies in this duality: it both invites and repels. If we eliminate the sense of threshold, spaces risk becoming mere corridors of flow, erasing the cultural memory and emotional tempo accumulated over generations. For example, cleaning or decorating the door threshold during holidays, grandmothers chatting on door thresholds, stepping over the threshold first in the new year (a tradition about who crosses the threshold first) – these small actions are connected to the architecture of doorways. Flattening doorways can contribute to the atomization of the community; if there is no threshold, there is no liminal meeting point.

So how can we reclaim the door entrance as a meeting place? Designers can start by restoring some of the layers and signals that make the entrance special. This doesn’t mean reverting to medieval doors for your office, but perhaps creating a small foyer that celebrates local art or provides a community bulletin board—something to linger over. Residential architecture can revisit the lost front porch or landing by designing modern equivalents (even a bench or an extension along the entry path) to encourage neighborly interaction at the threshold. In public buildings, making entrances intuitive and human-scale (rather than just large glass voids) can help—using materials that invite touch, including doors that users can choose to open manually (giving a sense of representation at the entrance rather than feeling like you’re sliding into a supermarket).

Urban design can also treat gateways—such as those to parks or campuses—as moments that convey identity and welcome (through signage, yes, but also through narrowing or widening roads, tree canopies, and changes in the texture of the pavement that your feet recognize as “I’ve entered”). These are contemporary interpretations of thresholds that still serve a psychological function.

Every door asks metaphorically: Who are you and what are you looking for here? Passing through the door should be a magical touch—a slight quickening of the heart in the face of the unknown beyond, or the comfort of returning home. As Bachelard thought, “the door… accumulates desires and temptations: the temptation to open the ultimate depths of being.” Our ancestors built thresholds that responded to this call—thresholds that protect but arouse curiosity, that isolate but connect. As architects, planners, and users of space, it is our responsibility not to allow the threshold of meaning to slip below the threshold of difference. In an age where we can instantly go anywhere, we must remember the wisdom of pausing at the door, of the handshake at the threshold, of the breath taken before entering. Through design and habit, we can revive the door as a meaningful pause—a place where external and internal life meet, reminding us that each transition offers an opportunity to recognize where we come from and where we are going.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.