Hostile Horizons: The Rise of Anti-Homeless Architecture

This is the quiet war waged not with weapons but with angled ledges and segmented benches. It represents a fundamental shift in civic design philosophy, where public space is managed through exclusion rather than inclusion. The horizon of the city becomes hostile, a landscape engineered to repel a specific human condition. Its rise signals a prioritization of aesthetic control and perceived order over communal care and basic human need.

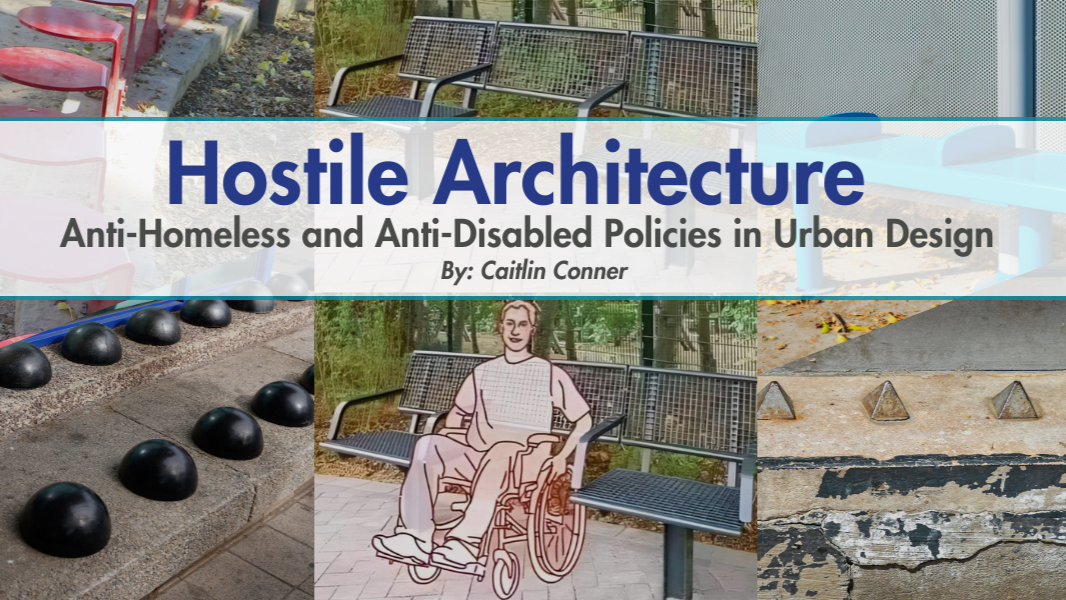

Defining the Invisible Fortress: What is Hostile Design?

It is architecture that uses form to dictate behavior, specifically to prevent resting, sleeping, or lingering. Unlike a fence or a wall, its hostility is often subtle, embedded in the everyday objects of the urban fabric. This creates an invisible fortress, a boundary felt rather than seen, that defines who belongs in a space and who is merely tolerated. It matters because it transforms shared civic ground into a selectively comfortable zone, legislating through concrete and steel.

From Benches to Barriers: A Taxonomy of Exclusion

The common bench is reimagined with armrests that segment seating, not for comfort, but to prevent lying down. Sloped window ledges and textured paving under bridges make reclining physically impossible and psychologically unwelcoming. Sprinklers timed for night hours and ambient noise or light installations serve as environmental deterrents. This taxonomy reveals a deliberate creativity, a perverse innovation focused on making human rest an engineering problem to be solved.

The Psychology of Discomfort: Design as a Deterrent

This design language operates on a subconscious level, using persistent discomfort to encourage movement. It creates an environment of sustained unease, where the body cannot find a moment of peace or a position of repose. The message is not one of outright prohibition but of gentle, relentless persuasion toward invisibility. This psychological dimension matters because it weaponizes discomfort, making the city itself an agent that asks certain people to leave.

Blending In: How Hostile Design Camouflages in Plain Sight

Its power lies in its mimicry of benign or even playful urban furniture. A jagged rock sculpture or a series of isolated stone stools can be praised as public art while serving a covert function. These elements borrow the visual language of normalcy, making criticism seem like an overreaction to a simple bench or a quirky ledge. This camouflage matters because it allows exclusion to be implemented without public debate, hiding policy within aesthetics.

Legal and Ethical Gray Areas: Regulation vs. Innovation

These designs often exist in a void of specific regulation, exploiting the gap between building codes and human rights. The innovation is in circumventing legal definitions of obstruction, creating spaces that are technically open but functionally inaccessible. This raises a profound ethical question about the ownership of the city and the right to exist in public without persecution. The gray area matters because it challenges us to define what kind of society we build when the letter of the law outpaces its spirit.

The Architect’s Dilemma: Intent, Commission, and Consequence

Every design begins as a pure intention, a vision of space and experience. This vision is then filtered through the commission, a negotiation of budget, client desire, and site constraints. The final built form is a record of these compromises, a physical consequence that outlives its creators. The dilemma lies in the gap between that initial ideal and the final impact, a space where architecture succeeds or fails its original promise. It is the story of every building, told in concrete and glass.

Client Briefs and Social Responsibility: Who Calls the Shots?

The brief is a map drawn by the client, outlining functional needs and aspirational goals. It holds immense power, directing resources toward specific outcomes and user groups. When a brief prioritizes luxury over accessibility, or profit over public good, it becomes a tool of social engineering. The architect’s responsibility is to question this map, to advocate for spaces that serve a wider community. Ultimately, the one who writes the brief holds the first pen in drafting the character of a city.

Material Choices as Weapons: The Cold Hard Facts of Stone and Metal

Materials are never neutral; they carry political and environmental histories. Choosing local stone speaks of permanence and place, while importing polished marble can signal global power and extraction. The selection of reinforced concrete or sleek steel frames is a declaration of economic system and technological might. These choices become weapons when they are used to intimidate, exclude, or create monuments to wealth. The true cost is etched into the landscape long after the building is complete.

Case Study: Public Space “Revitalization” and Its Unseen Costs

Revitalization is a seductive word, promising renewal and community benefit. The unseen cost is often the quiet erasure of existing social fabric, replacing informal gathering spots with managed, commercialized plazas. New benches designed to deter sleeping, perfectly calibrated lighting, and private security create a space of control, not congregation. The result is a public space that looks successful on a brochure but feels sterile to the soul. It trades authentic, messy life for a curated, and often exclusionary, experience.

Alternative Histories: What Could Have Been Built Instead?

For every realized building, there exists a ghost city of unbuilt alternatives. These are the roads not taken, the designs lost to committee or cost. Considering them is an act of critical imagination, revealing the values and fears of a particular time. It asks what community need was overlooked for a statement tower, or what ecological integration was sacrificed for a faster build. These alternative histories are not mere nostalgia; they are a vital tool for rethinking our present priorities. They remind us that our environment is a collection of choices, not inevitabilities.

Reclaiming the City: Critique and Compassionate Alternatives

The city is a shared resource, a collective project that belongs to all its inhabitants. Hostile architecture represents a failure of this shared vision, turning public space into a landscape of exclusion and control. Reclaiming it begins with a critique that names this alienation for what it is: a design choice that prioritizes order over humanity. Compassionate alternatives imagine the city not as a fortress to be defended, but as a home to be nurtured, where care is embedded in concrete and bench design. This reclamation is an act of urban empathy, seeking to welcome rather to repel. It asks designers to see the street from the perspective of those with nowhere else to rest. The goal shifts from managing perceived problems to supporting human dignity. Ultimately, a compassionate city is a stronger city, one that builds social resilience through inclusion, recognizing that public space is the stage where community is either fractured or forged.

Activism and Awareness: Documenting and Challenging Hostile Design

Activism begins with seeing the invisible. It trains the public eye to notice the subtle spikes, the slanted ledges, and the partitioned benches that dictate who belongs. Documenting these features creates a shared vocabulary of exclusion, turning individual frustration into collective evidence. This awareness is a powerful catalyst, revealing that our surroundings are not neutral but actively shaped by specific intentions. Challenging this design language moves evidence into the realm of public discourse. Activists reframe these features from ‘crime prevention’ to ‘poverty management’, questioning who benefits from this sterile order. Their work makes the political nature of design undeniable, insisting that public space must serve the public in all its forms. This is a fight for the soul of the city, arguing that comfort is not a privilege but a right in the shared urban home.

Principles of Inclusive Urbanism: Designing *For* People, Not Against Them

Inclusive urbanism starts with a fundamental inversion of perspective. It designs for human needs first, considering rest, play, and gathering as essential activities. This philosophy measures success by how well a space accommodates the young, the old, the tired, and the marginalized. It understands that a bench is not just a place to sit, but a node of community and a gesture of care. The principle is proactive generosity, building in comfort rather than engineering it out. It chooses materials that are inviting to the touch and configurations that foster connection. Inclusive design asks, “How can this space support more life?” rather than “How can it prevent misuse?” It results in environments that feel permissive and rich with possibility, where the design itself expresses a quiet welcome to all.

Showcase: Global Examples of Empathetic and Supportive Public Spaces

From the playful water features of Singapore’s public parks to the flexible, modular seating of Barcelona’s superblocks, empathetic design takes many forms. These spaces share a common thread: they trust the public. They provide the tools for interaction, like movable chairs or accessible shade, and allow people to define their own use. The result is organic vitality, where the space feels alive and adaptable to the rhythms of daily life. In Medellin, Colombia, library parks in once-marginalized neighborhoods demonstrate how monumental investment in beauty and accessibility can transform social fabric. These are spaces that dignify, offering not just services but also pride and a sense of belonging. They prove that supportive design is an investment in social infrastructure, creating anchors for community that are both physically and symbolically uplifting.

The Role of Policy: How Legislation Can Shape a More Humane Built Environment

Policy translates ethical intention into enforceable standards. It moves inclusive design from a voluntary ideal to a foundational requirement. Legislation can mandate accessibility, set minimum standards for public seating, or ban explicitly hostile features like anti-homeless spikes. This creates a level playing field, ensuring that humane design is not a rare exception but a consistent expectation. Good policy acts as both a shield and a catalyst. It protects the vulnerable from exclusionary practices and catalyzes innovation by setting clear, compassionate goals for developers and designers. When cities adopt ordinances that prioritize universal design and public comfort, they institutionalize empathy. This shifts the entire profession’s trajectory, making the humane choice the standard choice in the built environment.

A Call to Conscience: The Architect’s Role in Social Equity

Architecture is never merely a service; it is a social act with profound consequences. Every drawing, every material specification, either reinforces the status quo or challenges it. The architect’s role, therefore, carries a deep ethical weight, a call to conscience that asks for whom we are building and to what end. To design is to make a world, and that world must be for everyone. This means advocating for the unseen user and questioning briefs that seek to exclude. It involves using one’s expertise to argue for generosity, accessibility, and warmth as core components of beauty. The architect shapes the physical stage of society, and in doing so, must consciously design for equity and encounter. The most enduring legacy is not a striking form, but a just and welcoming space that nurtures the human spirit.

Dök Mimarlık sitesinden daha fazla şey keşfedin

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.