“Architecture is an art of reconciliation between ourselves and the world, and this reconciliation takes place through the senses.” – Juhani Pallasmaa.

Even if we lack the words to describe them accurately, places speak to us. Cultures around the world have developed unique spatial concepts that encode ways of living, feeling, and relating to others—concepts that are truly untranslatable. These terms are more than linguistic curiosities; they are keys to understanding how architecture became a form of language. From the Japanese appreciation of the silence between walls to the Danish quest for comfort in the home, such concepts reveal a deeper cultural logic written into buildings and cities. As we explore five critical questions, we embark on a narrative journey through these ideas: how culturally specific words for space shape everyday life, whether architecture itself constitutes a kind of language, what is lost (and found) in translation as designs become global, whether new spatial “words” can be invented for emerging needs, and how architects should navigate concepts they cannot fully translate or grasp. The aim is both academic and poetic—to understand space as a kind of cultural text and learn to read it with humility and imagination.

Culturally Specific Spaces: When Design Speaks Local Dialects

Every culture has key words related to space—terms that defy direct translation because they embody an entire way of life. Consider the Japanese concept of Ma (間), often translated as “space,” “pause,” or “the space between.” In a traditional Japanese home, ma is everywhere: the space between sliding shoji screens, the regular corners of a tatami room, the silent pauses in conversation or tea ceremonies. “A space filled with possibilities, like an unfulfilled promise,” it is a deliberate emptiness that gives meaning to what surrounds it. A minimalist tatami room may appear sparsely furnished to Western eyes, but its emptiness is “the physical manifestation of a spiritual concept”. Rather than a deficiency, it is a ma designed pause—the architectural equivalent of a rest in music—that allows occupants to breathe, think, and appreciate the value of being in that space. Japanese architect Ryue Nishizawa once noted that when designing, one must shape not only the building but also the emptiness it contains. At its core, terms like ma encode a cultural rhythm of life that harmonizes with intervals of subtlety and tranquility.

A traditional Japanese washitsu (tatami mat room) with paper shoji screens. The sparse design represents intentional space or pauses between elements, emphasizing the importance of surrounding objects, light, and textures. In Japanese culture, space is not merely a backdrop for life but an active component that creates the “music” of daily life through silence and emptiness.

Other untranslatable spatial words also serve a similar cultural shorthand function. Take, for example, the Danish term “hygge,” which is often translated as “coziness” in English but conveys much more. Hygge describes an intimate warmth—a sense of contentment or well-being (considered a defining feature of Danish culture). The glow of candlelight in a living room on a winter evening, friends gathered around a wooden table, the soft textiles and warm neutral colors of a home designed for comfort. A Danish family can openly arrange their living spaces to encourage hygge, creating a corner for togetherness and incorporating touches that engage all the senses in a delicate harmony. The rise of hygge in global decor trends highlights how a word rooted in local climate and social rituals (long, dark winters that encourage closeness) has traveled far and wide. — yet outside Denmark, “hygge” can easily be reduced to a style aesthetic (think Instagrammable blankets and cocoa) detached from its cultural roots. This points to a danger we will explore further: when such terms are adopted without their full context, something vital can be lost in translation.

In the Arabic-speaking world, the term “Liwan” can be used to refer to a specific area in traditional Levantine houses. Liwan is not just a hall or porch; it is typically a long, vaulted front room that opens onto a courtyard or street, often with one side completely open or covered with arches. In a classic Damascus or Beirut house, the liwan is the social center—where guests are welcomed with mint tea, evening breezes waft through the courtyard, and family members often relax on cushions along the diwan (seating platform) that lines the edges. The shape and layout of the liwan encode cultural priorities: hospitality, ventilation in a warm climate, and a degree of privacy from the public façade to the private interior. It is significant that there is no single word in English for liwan—we might say “veranda,” “porch,” or “central hall,” but none of these captures the open-closed living and ceremonial reception that is unique to the liwan. Attempting to design a Middle Eastern-inspired home without understanding the role of the liwan can result in a shallow pastiche. Liwan, like ma or hygge, is a spatial sentence in a culture’s language—to truly speak it, one must grasp its social usage grammar and symbolism.

Even seemingly simple elements can carry nuances that are impossible to translate. The best example of this is “Baraza” on the Swahili coast of East Africa. Baraza is a built-in bench made of stone or mud that surrounds the entrance to a house or runs along a veranda. However, calling it simply a bench misses the point: baraza benches have been the focal point of community life in places like Zanzibar for centuries. They evolved as a way for men to receive visitors in a semi-public open space—preserving the privacy of the home (and, in accordance with Islamic tradition, the women inside) while still offering hospitality. Neighbors gather at the baraza every evening to gossip, play mancala (bao) or cards, sip coffee, or simply watch the world go by. In Stone Town’s narrow streets, barazas even serve as raised sidewalks during monsoon floods. In short, the baraza is not just an architectural feature; it is a social institution. Imagine a Western architect tasked with designing a residential complex in Zanzibar—if they omit the baraza, they would inadvertently erase a daily forum for social interaction. And if a baraza-like element is transplanted into a different context (e.g., decorative bench extensions in an American suburban development), it may look charming but lack the social scenario that gives it meaning. These examples underscore an insight from linguistic anthropology: some spatial concepts are so tied to a culture’s way of life that they cannot be fully explained outside of it. To use a linguistic term, they are untranslatable. Nevertheless, architects increasingly find themselves working across cultures, attempting to interpret these local “dialects” of space.

Before examining the dangers of mistranslation, let us savor what these terms imply. Ma teaches us to focus on emptiness and space—a spatial tempo that values the unbuilt as much as the built. Hygge illuminates how design can promote emotional well-being and togetherness as an antidote to environmental harshness. Liwan offers a formal solution to climatic and social needs—a space that cools and connects. Baraza speaks of a public-private mix, a community threshold. Each word is like a poem distilled into a single term about how people should live in a space. These words, with their untranslatability, remind us that architecture is not universal, but highly cultural. A room is never just a room—it can be a washitsu, a salon, a majlis, or a parlor, each carrying its own connotations. To create good design, one must be an anthropologist and linguist attuned to these subtle spatial vocabularies.

Is Architecture a Universal Language or a Collection of Dialects?

If every culture has its own spatial vocabulary, we may ask: Can we still speak of architecture as a language that is understood across cultures? Or is every space too different to be “read” as part of a universal dictionary? This debate has long fascinated philosophers and architects. While structuralists once sought to find the grammar of space, postmodernists played with architecture as if it were a system of signs and metaphors. Indeed, there is meaning in which architecture communicates—but perhaps not directly, one-to-one, like a spoken language. Rather, architecture operates more closely to what Amos Rapoport called a “nonverbal form of communication.” This is a “language” composed of clues, contexts, and arrangements that we learn to interpret by living within a culture.

Consider a simple architectural element: a door. Universally, a door symbolizes a threshold, a passage from one realm to another. However, the meanings of thresholds vary greatly. In a Japanese genkan (entranceway), the raised interior floor and the tradition of removing shoes “say” that crossing this threshold is also a purification ritual—you leave the outside world (and your shoes) behind. The low lintel of a medieval English cottage may force you to bow your head as you enter—a physical sign of respect or humility. With its ornate double doors and entrance, a large 19th-century Parisian townhouse speaks of the transition from the formal and public to the private. The threshold is a word that exists in every architectural language, but it is pronounced with a different emphasis and meaning in every region. For example, in traditional Turkish houses, there is a cumba, a protruding cumba surrounded by a lattice—it allows women to observe the street without being seen from the inside; it is similar to a cumbaya or a mashrabiya, but it is unique in its distinctive shape and cultural role. Compare this to the iconic “Juliet balcony ” in France (a shallow railing in front of French doors) – just large enough to step out, lean over, and chat with the street. Both the cumba and the Juliet balcony act as intermediaries between the inside and outside, but while one conceals, the other reveals. In reality, they are like synonyms with very different connotations. Architectural communication can establish—suggest openness, security, hierarchy, intimacy—but to truly understand the message, we need to share some cultural context.

Semioticists such as Roland Barthes and Umberto Eco have argued that architecture lacks the rigid “grammar” of spoken language. You cannot combine a column or knock down a roof. Indeed, Rapoport notes that the built environment is “probably devoid of the linearity of language… [language] does not allow for a clearly articulated set of grammatical rules.” Instead, the meanings of architectural elements are often associative, contextual, and redundant (a message is repeated in multiple ways). We derive meaning from a series of clues—just as we read body language. Just as the significance of a smile depends on cultural norms (polite in one culture, sincere in another), so does a spatial gesture. A courtyard surrounded by columns “speaks” of collective gathering and relaxation—but in an Islamic context, it may also signify privacy and an inward-looking family life protected from the street, while in a Mediterranean town, it may celebrate shared outdoor living. These are architectural dialects.

Nevertheless, it can be argued that some spatial experiences are almost universal, rooted in human biology or psychology. For example, environmental psychologists (drawing on Jay Appleton’s theory) often refer to the concept of “view and refuge.” It is said that people everywhere appreciate environments where they can see without being seen—a vantage point and a hiding place rolled into one. This may explain why reading nooks in attics, window seats, or alcoves under staircases are so comfortable in many cultures, or why houses with expansive views from the top are so beloved. Yet even “hope-sanctuary” is interpreted through culture. A Japanese garden provides sanctuary with dense vegetation and semi-hidden benches (embracing the wabi-sabi aesthetic of imperfection), while a Swedish home may provide sanctuary with soft lighting and window curtains, in the hygge style. The language of space has dialects, and misreading them can lead to design flaws.

Architecture also carries symbolic languages that require cultural literacy. A dome can universally imply the sky, but in the 16th century, the dome of a mosque for an Ottoman subject echoed the dome of Islam. Color, texture, orientation—all can be symbolic. French phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard wrote about how houses hold poetic images for their inhabitants: attics are realms of dreams, cellars are repositories of the unconscious, and corners of rooms are filled with loneliness. These interpretations are not exactly the same for everyone, but they resonate widely because they touch on deep human experiences (darkness, height, enclosed spaces). In this sense, architecture is like a shared poem of space written by each culture, but the human body and spirit provide a common ground for understanding most of it. A well-designed threshold, a well-proportioned room, a well-lit courtyard—even if we cannot articulate why, these things feel right to us. The quote from Pallasmaa above points to this universality: architecture reconciles us with the world through our senses. We don’t need to speak Japanese to feel the tranquility of a Zen rock garden; the composition of the space communicates on a nonverbal level.

So, is there a universal architectural language? Perhaps only in the sense that we all share the same basic syntax of bodily experience: gravity, light, sound, movement, shelter. However, the vocabulary and idioms are richly diverse. Architecture is more like a tapestry of dialects, occasionally containing cognate words, than an Esperanto. Just as music is a universal language in terms of emotion but specific in form (a raga is not a waltz, but both can move us), architecture can touch us across cultures but still express different things. It is important to accept this duality. It reminds architects to avoid assuming that a design speaks for itself on a global scale. Without a shared vocabulary, miscommunication is likely. As we globalize design, this becomes an urgent issue: are we transforming these dialects into a generic international style, or are we learning to be multilingual—fluent in multiple spatial languages?

Loss in Translation: When Local Ideas Go Global

Globalization has swept many architectural elements that were once local into a worldwide exchange of styles. At first glance, this cross-pollination is exciting—inspiration knows no bounds. However, what happens when a concept deeply rooted in one culture is transplanted into another without its original context? Often, we are left with a copy that has lost its original spirit. In architecture, the danger of misinterpretation is real: a form or term may be adopted for its visual appeal, leaving behind its social, environmental, or spiritual logic. The result is a kind of flattening, where designs around the world begin to look superficially similar but no longer express the meaning they once did.

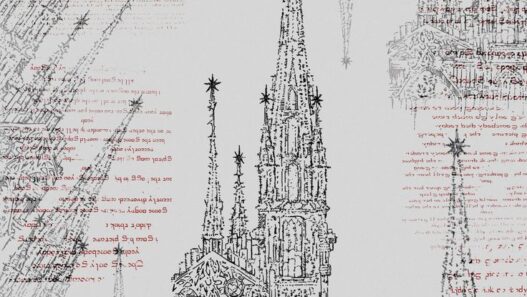

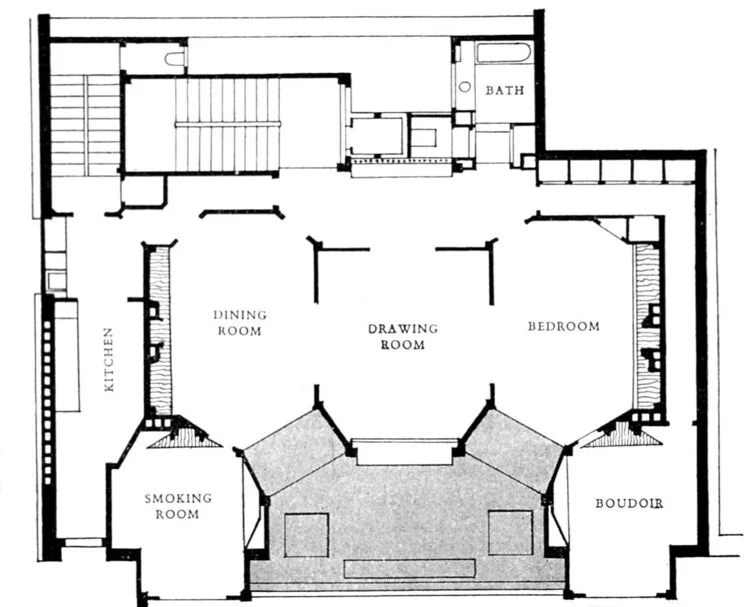

A traditional mashrabiya covering the windows of a residence in Cairo. This carved wooden lattice protrudes from the facade, creating a ventilated and shaded niche from which the inhabitants can look out while remaining hidden from view. For centuries, mashrabiya have been an integral part of Arab homes, filtering the harsh sun and directing breezes to cool interior spaces while also respecting privacy (especially for women). The design is both functional and cultural—a beautiful latticework with social significance.

One of the most symbolic examples is the ornate lattice window known as a maşrabiyedir, which is widespread in traditional Islamic architecture (from Morocco to India). As previously explained, the maşrabiye is not merely a decorative element but also a performative tool. In the hot Middle Eastern climate, the intricate wooden lattice diffuses sunlight, creating dappled patterns instead of harsh glare, and allows airflow for passive cooling—all while serving as a one-way screen for those inside. It also carries deep cultural symbolism: a point of connection and separation, a “permeable protection that welcomes without excluding,” embodying the balance between hospitality and seclusion in Islamic homes. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, architects around the world fell in love with the visual pattern of the mashrabiya. Suddenly, we began to see luxury residences in London or skyscrapers with facades made of geometric screens in Beijing. However, these are often maşrabiya motifs that have been diverted from their original purpose. A laser-cut metal panel serving as a glass curtain wall merely decorates the facade, while the building behind it remains completely closed and air-conditioned—the curtain no longer opens, no longer breathes. This is mere window dressing; it is not the eyes through which the building sees and breathes. As one critic put it, this is a transition from climatic/social function to aesthetic imitation—the mashrabiya pattern has been commodified into a fashionable texture, a kind of surface appliqué. We could also call this meaningless mashrabiya.

Mashrabiya‘s modern reinterpretation: Designed by Jean Nouvel, the Institut du Monde Arabe (1987) in Paris features a facade composed of metallic diaphragms that open and close like camera irises. Here, technology has been used in an attempt to translate the mashrabiya’s light modulation logic into a contemporary context. However, many buildings constructed in recent years have adopted mashrabiya-inspired geometric facades merely as static decoration. Without a cultural narrative or adaptable function (such as genuine climate sensitivity), such screens risk becoming hollow motifs—reflecting a local idea but reduced to a “diluted, distorted, or… commercialized” global design trope.

Of course, not all translations are bad. There are also sensitive reinterpretations: Jean Nouvel’s Institute of the Arab World in Paris redesigned the mashrabiya using hundreds of mechanical openings on the south facade to control light—a high-tech tribute to the traditional screen. Towers like Al Bahar in Abu Dhabi have also proven that old principles still work by using dynamic geometric panels to block sunlight. But these are exceptions. More commonly, we encounter what we might call local appropriation: taking a form out of its cultural ecosystem and placing it in a new one, much like uprooting a plant and planting it in foreign soil with little connection to its original context. Architectural appropriation originally meant “to dilute or spoil.” Consider the trend of “Moroccan curtains” in contemporary interior design—you will see curtain panels sold in catalogs to bring an “exotic feel” to an apartment. There is no mention of the fact that these moucharabieh curtains historically cooled homes in North Africa or facilitated gender-segregated socializing. Similarly, the courtyard house, a beloved typology from ancient Rome to China and Iran, has been reduced to an aesthetic feature in some modern mansions: a small garden or pool in the middle of a massive house, perhaps beautiful but no longer the gathering place for a large family or the sole source of cross-ventilation as it was in its original setting. A shallow pool called a “courtyard” in a hotel lobby may evoke tranquility, but it does not connect to daily life like a real courtyard in a local home where children play under the watchful eye of a careful grandmother and evening meals are enjoyed under the stars. Although open-plan modern layouts claim to be “inspired” by courtyards, when they lack the social and climatic logic (privacy, gender segregation, cooling) that gives courtyards their form, this is a case of lost translation. Academic studies point out that traditional courtyards provide not only environmental benefits but also a cultural core for families and communities, and that this is difficult to replicate in modern designs that use open concepts without glass atriums or surrounding social frameworks.

In the accommodation sector, we have seen the transition from ryokan to boutique hotels. Ryokan is a traditional Japanese inn with tatami rooms, shared baths, and hosts who serve tea while kneeling—all part of a specific hospitality choreography. Many boutique hotels around the world are now trying to evoke the ryokan experience—a minimalist room with tatami mats or a yukata robe, perhaps with a rock garden in the courtyard. However, if the hotel does not embrace omotenashi (the Japanese concept of hospitality) or the slower pace of the seasonal, tactile experience offered by a ryokan, then these design nods remain superficial. A guest can sleep on tatami in New York, but if there’s a taxi honking outside the window and the schedule is rushed, are they truly experiencing what a ryokan’s spatial language conveys (rest, ritual, harmony with nature)? The risk is that by globalizing these concepts, we are creating a pastiche—a cultural image stripped of its original meaning.

Why is this important? It could be argued that forms can evolve into new meanings in new places, and to a certain extent this is true. However, when architectural elements that carry centuries of wisdom are copied without being understood, we lose the opportunity to learn why they evolved. While a mashrabiya pattern pasted onto a skyscraper as decoration does not mean much in terms of sustainability, understanding mashrabiya can truly inspire climate-sensitive facades. There is also the loss of “emotional nuance and memory”. Local architecture often embodies intangible heritage—ways of socializing, methods of coping with the environment, symbols that resonate with local stories. Reducing these to stylistic motifs can feel like watching a sacred poem of the culture of origin turn into a jingle. Architecture, as cultural memory, deserves respect. As Rapoport and others have pointed out, the built environment carries meanings that users are deeply attached to. When exported, these meanings can be misinterpreted or even erased, leading to environments that appear cosmopolitan but are in fact nowhere.

A striking example is how some contemporary developments in the Middle East have superficially appropriated local forms. In places like Dubai, luxury villas feature courtyards that are more decorative than functional, or mashrabiya screens fixed to high-rise buildings and backlit solely to create an impact. Meanwhile, new buildings often ignore the principles that necessitated these local features—relying on air conditioning instead of cross-ventilation, or poorly orienting glass towers toward the sun, which requires curtains to serve as afterthought sunshades. Critics point out that this approach turns living traditions into stage props. It is the architectural equivalent of a fast-food chain serving sushi burritos—fusion, yes, but perhaps missing the spirit of both cuisines. The flattening of meaning also tends to encourage a kind of design monoculture: the same sleek patterns and forms are repeated everywhere, regardless of local context (here a mashrabiya motif, there a green wall, the “open-plan courtyard” concept in many corporate headquarters). Within this framework, there is an increasing call for critical regionalism, which means designing with global awareness but local content to avoid the blandness of an international style that is a “one-size-fits-all” solution.

In summary, when local concepts are globalized, something is often lost in translation: climate-sensitive wisdom, social choreography, spiritual symbolism—the reasons why these forms emerged. This loss impoverishes architecture as a whole. However, as the next question explores, perhaps new contexts can also be found in translation—new spatial languages that speak to contemporary life may emerge.

Towards New Spatial Languages: Can We Invent Words for Evolving Lifestyles?

Language develops inevitably – new experiences require new words. The same is true in architecture: as living conditions change, designers often improvise new spatial solutions, which eventually acquire names (or beg for them). The modern age has already given us terms like “skyscraper,” “suburb,” “open plan,” and “airport,” which meant nothing to our pre-industrial ancestors. Today, we stand at another crossroads of rapid change. Digital technology, global migration, climate change, pandemics—these forces are reshaping how and where we live. Are such new contexts creating their own untranslatable spatial concepts? Or should we continue to borrow and adapt the old ones? In other words, can we create new words in the language of architecture—words that future generations will struggle to translate because they are so deeply rooted in our time?

Consider the lifestyle of a digital nomad in the 2020s. While traveling, this person may want a combination of home, office, and social lounge where they can focus on their laptop and meet with travel companions for inspiration. In response, the design world has witnessed the rise of “co-living” and “co-working” spaces that blend home and shared living spaces. These are neither fully hotels, nor fully dormitories, nor fully offices. They are a new typology. Some have started using terms like “hackerpace home” or “workcation hub,” but there is no universally accepted term yet. Perhaps in ten years, we will have an accepted term (and perhaps even local dialects). What matters is that architects are effectively inventing spatial models to support an unprecedented lifestyle—bedrooms that double as private offices and large communal kitchens that serve as both cafes and family tables for unrelated residents. The degrees of proximity and rhythms here are new: disinterested people living together for short periods, balancing privacy (a quiet partition for a Zoom meeting) and community (a lively lounge for Friday events). We could argue that a new concept is emerging that encodes the values of flexibility, networking, and temporary belonging—we might call it the “global nomad hearth” or something else. While parallels can be drawn to historical caravanserais or hostels, the scale of digital connectivity and the voluntary nature of this lifestyle set it apart. It deserves its own spatial vocabulary.

Then there is the grim reality of refugee camps and migrant settlements – essentially instant cities born out of crisis. These places are often designed (or initially organized) by agencies in utilitarian grids, but residents quickly adopt and adapt them, creating areas that official planners do not name. In long-standing camps, people create small “self-organised care areas“, such as courtyard-like clusters of tents among trusted families or small market streets with informal shops where aid is distributed. Such patterns may not yet have official architectural names, but they represent spatial responses to conditions of temporariness, high density, and cultural clash. Is a row of UNHCR tents that has turned into an improvised market just a market? Or is it a new hybrid, half market, half community center, half survival strategy? Architects and anthropologists studying camps have begun documenting these nuances and have noted that when people are forced to rebuild community structures from scratch, new spatial vocabularies emerge. We can see terms like “cluster settlement” or “housing hub” entering the discourse to describe areas in camps that have become semi-permanent neighborhoods. Humanitarian aid design has also introduced innovative concepts such as “maker space,” which provides tools for refugees to personalize their shelters, into camps. This is a new type of space born out of contemporary needs and is essentially a community workshop embedded in a temporary city. Language is evolving to define it.

Our most recent global experience with the COVID-19 pandemic has also triggered spatial innovation. Homes suddenly had to serve as offices, classrooms, gyms, and more. Architects and furniture designers worked to create small, soundproofed corners for video calls and focused work within a home, which some have dubbed “Zoom rooms” or “flexible spaces.” Before 2020, very few people had the concept of a dedicated video conferencing booth in their homes; now it’s a selling point for real estate. The term “Zoom room” itself may or may not stick around, but the spatial idea will remain as remote/hybrid work continues. Similarly, the idea of a “quarantine wing” or at least a room with an attached bathroom to isolate a sick family member has begun to catch on. One could say we are seeing the rebirth of something akin to the infirmaries of previous centuries, but in a modern form. These spaces emerged as critically important almost overnight, and initially we had no vocabulary for them. Over time, design may formalize them—perhaps future apartment listings will advertise “flexi-niche” spaces, much like today’s “study” or “utility” rooms. If the concept gains traction, a new term may also emerge.

When creating new spatial words, we sometimes borrow from other languages because they are more advantageous. For example, the Japanese term “Tsukimi” (moon viewing) has recently been used in some designs for rooftop terraces intended for quiet contemplation at night—essentially reimagining an old concept for a new design ethos of mindful living in cities. It remains to be seen whether this term will catch on abroad, but it shows how designers are scouring the world’s lexicon for ideas that will appeal to contemporary aspirations (in this case, urbanites seeking a cosmic connection). Similarly, “Hygge” has been adopted internationally as the label for a broader movement toward comfort in uncertain times. When a new phenomenon emerges, we often look to see if there was already a word for something similar somewhere else.

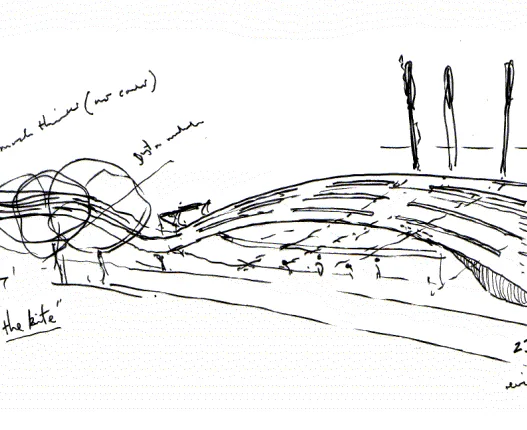

Conversely, architects invent imaginary terms to summarize a manifesto or vision and hope that they will catch on. The late architect Christopher Alexander gave us the concept of “Pattern Language”—not a single spatial design, but an entire approach to producing new ones from combinations of basic patterns such as “light on both sides of every room” or “street cafés.” Although his patterns had simple names, the idea was to enable everyone to create their own local design language. Alexander was, in a sense, trying to pre-translate architecture by identifying universal patterns. However, even he acknowledged that each society would give these patterns its own unique expression.

Today, the cutting edge of spatial encounters may be hybrid digital-physical spaces. Think of augmented reality workplaces and VR meeting rooms—can these be considered architectural spaces? Some say they can, and therefore we may soon need words to describe designs that bridge the gap between virtual and physical architecture. Terms like “metaverse lobby” or “virtual plaza” could become commonplace if we regularly experience mixed reality environments that still utilize spatial awareness (such as gathering around a virtual fountain in a digital city square). These will undoubtedly be neologisms with no direct equivalents.

An enlightening example of language creation comes from local and environmental design dialogues. The 2023 KoozArch manifesto stated that embracing indigenous concepts can expand the vocabulary of architecture. Referring to the Ka’aporca word “taper,” the manifesto stated that this word refers to an old forest shaped by human hands. In Western languages, there was no single term that oscillated between the ideas of “wild” and “managed” to describe this relationship between humans and forests. By learning about taper, designers can think of landscapes not as untouched wilderness or formal gardens, but as something in between—an ecology created together. This is a powerful example of how borrowing a term can actually fill a conceptual gap in contemporary practice. For those unfamiliar with the concept, it is a new spatial concept and its adoption in regenerative design circles is foreseeable. Similarly, architects such as Lesley Lokko have coined terms like “Afrourbanism” or “Endotic architecture” (borrowing a term that means the opposite of exotic—focusing on the overlooked everyday) to challenge new ways of thinking about design. These may or may not endure, but they indicate a drive to name the new and the needed in the field. The words of the future may also be reinterpretations of old words—even a term like “crisis” could be redefined in design contexts in a less negative way, such as “transformative change,” and may require a new vocabulary to frame how architecture responds to planetary challenges.

Spatial languages are both inherited and invented. We don’t start from scratch—we carry with us an unconscious spatial vocabulary from our childhood (the meaning of a porch, a fireplace, a park) and inherit a formal vocabulary from past builders. However, when our experiences stretch these inherited words to breaking point, we create new ones. These can be intentional (inventing a term in a design article) or organic (users giving an area that designers haven’t labeled a slang name). The exciting part is that we are in a rapid evolutionary process; therefore, we should expect and even strive to enrich the vocabulary of architecture. This is not just about naming new shapes; it is about crystallizing new relationships between people and spaces. Tomorrow’s new untranslatables will reflect changes in the way we live: perhaps a concept for the “feeling of a home that moves with you” (for a nomadic age) or a word for “climate-healing space” in environmentally conscious design. These may sound utopian, but so did the “social distancing” space or the “community refrigerator” space before we actually needed them. The challenge for architects is to imagine these spatial neologisms and create prototypes—and most importantly, to imbue them with real cultural meaning so they don’t become empty buzzwords. This leads to the final question: How should architects proceed responsibly when working with concepts they don’t fully understand—whether old and foreign or new and ambiguous?

Designing with What We Don’t Fully Understand: Towards Architectural Humility

Every architect at some point finds themselves designing for a culture or context other than their own. This could be a Western architect incorporating a jali screen into a building in Mumbai, an urban planner designing for an informal settlement they have never lived in, or simply a young architect trying to navigate an older local language. In these moments, one is essentially translating. The words (concepts, forms) you use come from outside your primary experience. How can you do this in a coherent way? If certain spatial ideas are untranslatable or only truly understandable from the inside, can someone from the outside use them appropriately?

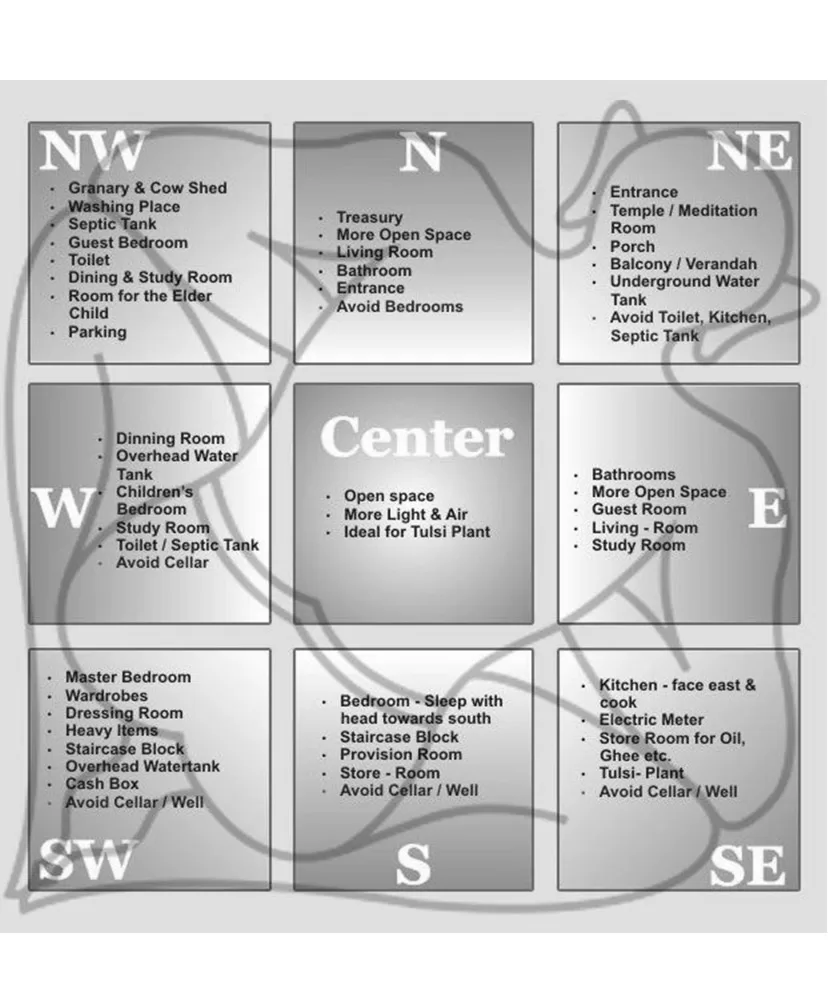

This is where architectural humility and listening become very important. Rather than viewing design as a blank canvas for personal expression, architects working across cultures should act more as translators and even apprentices. As noted in an article on cultural ethics in architecture, it is vital to establish deep relationships with local narratives, experts, and community representatives in order to understand the layers of meaning behind a tradition. In practice, this may mean spending months researching, learning from anthropologists or local artisans, observing daily life, and inviting criticism from those within the culture. An architect, for example, may never fully master the principles of Hong Kong’s feng shui or India’s Vastu shastra, but by consulting experts in these traditions, they can avoid obvious missteps and perhaps find respectful, creative ways to integrate these concepts. This is similar to learning a language well enough to write a decent poem with help, even if you will never have the intuition of a native speaker.

Participatory design is a powerful methodology in this regard. Rather than acting as a lone author, the architect becomes a facilitator who involves the local community (the real experts on their environment) in the design process. Consider a foreign architect tasked with designing public housing in rural Nepal. A top-down approach might result in a stylish “sustainable” prototype house that wins awards but alienates its residents. In contrast, a participatory approach seeks to understand how villagers use space, their daily habits, and what they value in a home (perhaps an outdoor cooking area or a space for ancestral rituals is non-negotiable) by organizing workshops with villagers and possibly local builders. Through collaborative workshops—essentially spatial dialogues—the design can emerge as a hybrid that combines the architect’s technical knowledge with the community’s lived experience. Such a process is clearly evident in the work of architects like Francis Kéré, who worked closely with villagers and used local materials and methods for the Gando Primary School in Burkina Faso. The result is not just a building, but also a source of pride and capacity-building for the community. When local wisdom guides innovation, it demonstrates how “cultural identity, sustainability, and functionality” can come together.

Indeed, collaborating with local artisans and cultural custodians fosters authenticity and mutual respect. This echoes the idea that the architect is not a master but a partner. For example, when restoring a historic building in China, a knowledgeable architect may consult traditional artisans on technical and proportional issues, effectively becoming a student of the local culture even as they bring new solutions to modern problems such as seismic reinforcement. Such collaboration also has economic and knowledge-sharing benefits—rather than sidelining local practitioners, it empowers them.

We should also discuss the ethics of appropriation and appreciation, which we mentioned earlier. This distinction lies largely in reputation and understanding. Architectural cultural appreciation means honoring the depth of meaning behind an influence and ensuring that your use does not trivialize it. This may include referencing the source culture in presentations and plaques or involving representatives of that culture in the project. It definitely involves considering whether a motif is being used simply because it is fashionable (and therefore reduced to a gimmick) or whether it is being reinterpreted in a way that is truly faithful to its original spirit. For example, applying a mashrabiya-like facade should ideally serve the climate and privacy as it did in the original—otherwise, its use should be questioned. The RTF guidelines advise architects to “be careful when using cultural symbols as aesthetic embellishments,” as each carries deeper meanings that should be considered. Essentially, if you cannot grasp this deeper meaning, perhaps you should not use the symbol superficially. Or, if you still want to use it for other benefits, then acknowledge your ignorance: admit that you are borrowing the form, not the full meaning, and be transparent about it. There is a concept that could be called “fluid ignorance”—recognizing one’s own limitations in understanding a cultural element, yet still working with it carefully, perhaps in a simplified or abstracted way without claiming to achieve the originality that may be beyond one’s reach. For example, an architect might say: “In creating this courtyard, we were inspired by the tranquility of Japanese Zen gardens—not to copy cultural elements directly, but to aim for a minimalist design that evokes calm. We consulted Japanese garden designers to avoid clichés.” Such honesty in the process and in the attribution can go a long way.

There is also a design strategy based on uncertainty. Architect Kengo Kuma often talks about combining tradition and modernity, mentioning that some things can be intentionally left open-ended for users to interpret—a kind of “productive uncertainty” where a space doesn’t force a single cultural reading but allows people to find their own comfort. This can be useful when you’re not an expert in the culture: instead of creating spaces with a didactic theme that could be misunderstood, create spaces with multiple layers. In a way, allow architecture to be a gentle framework that local culture can later imbue with meaning through use. For example, if you don’t fully grasp the concept of asha (whatever this term means spatially in Swahili), instead of trying to design a space that explicitly “does” it, you could design a flexible shared space and invite the community to shape its final character—paint it, tile it, ritualize it — so that the spatial meaning is created by them.

The work of international architects in local communities is an exemplary scenario. A respectful approach typically involves designing together with “cultural custodians”—elders, local designers, knowledge holders. For example, when building a First Nations cultural center in Canada, indigenous architects or artists may serve as co-leaders to ensure that stories and cosmology find an authentic architectural expression. In this case, the foreign architect acts as a technical translator or facilitator for the community’s vision rather than imposing their own vision. This reverses the scenario: the users become translators who teach the architect their own language.

Finally, designing with concepts that cannot be fully grasped requires a mindset that values the process rather than the ego. This is consistent with the idea that the architect should be a listener rather than a hero. In practical terms, this means doing your homework (academic and oral history research), being on site (sometimes living there for a while), and iterating designs through continuous feedback loops with local people. It also means being prepared to throw out a flashy idea if those who understand the culture point out that it is inappropriate or superficial.

When done well, cross-cultural design can produce striking hybrid languages—not pastiches, but creoles. In linguistics, creole languages emerge when languages blend over generations to form a new and fully fledged language. Similarly, architecture can create richly layered creoles. Consider the work of Balkrishna Doshi in India, who blended Le Corbusier’s modernism with Indian spatial sensibilities, or contemporary designers in Singapore who bring together Malay, Chinese, Indian, and modern influences in new tropical architectures. The works of these designers cannot be easily translated into a single cultural term—they are new languages born from understanding different parents.

Ultimately, responsibility lies in accepting the limits of one’s understanding and actively seeking guidance. Respect, collaboration, and originality should be fundamental. If architects approach foreign concepts with humility—almost like a traveler learning local customs—they can avoid the worst pitfalls of misuse. Beyond that, they can expand their own ways of seeing space. Designing with things we only partially understand can be an opportunity to learn from those who do understand them and make the project more fluid in the end. In a globalized world, no architect can remain monolingual. The best become bicultural or multicultural designers who can think and create in multiple spatial languages. However, they never assume that their native languages are fluent—instead, they act as careful translators, always double-checking with those who speak the native language of the space.

Returning to our main metaphor: language as architecture, words as spaces – words that cannot be translated are often the most beautiful and meaningful. We can appreciate them, borrow them, even create new ones, but we must also respect their integrity. A Japanese ma, a Danish hygge, an Arabic mashrabiya, a new “digital nomad co-living space,” an emerging refugee market—each is a line in the great poem of architecture. As the architects, writers, or readers of this poem, our task is not to flatten and render meaningless the verses in translation, but to strive for a nuanced understanding and creative interpretation. In doing so, we keep the deeper cultural logic of architecture alive and evolving. After all, the language of space is always expanding—and we are all its lifelong students.