We didn’t just lose a marketplace. We lost public life. We lost a place where everything—buying bread, debating prohibitions, meeting friends, and witnessing the clash of new ideas—took place in a single open, walkable gathering space. In Greek cities, the agora brought together politics, commerce, rituals, and everyday chance encounters; its disappearance means our cities must now find other ways to weave these threads back together.

The Historical Significance of the Agora

The Origins of Ancient City Planning

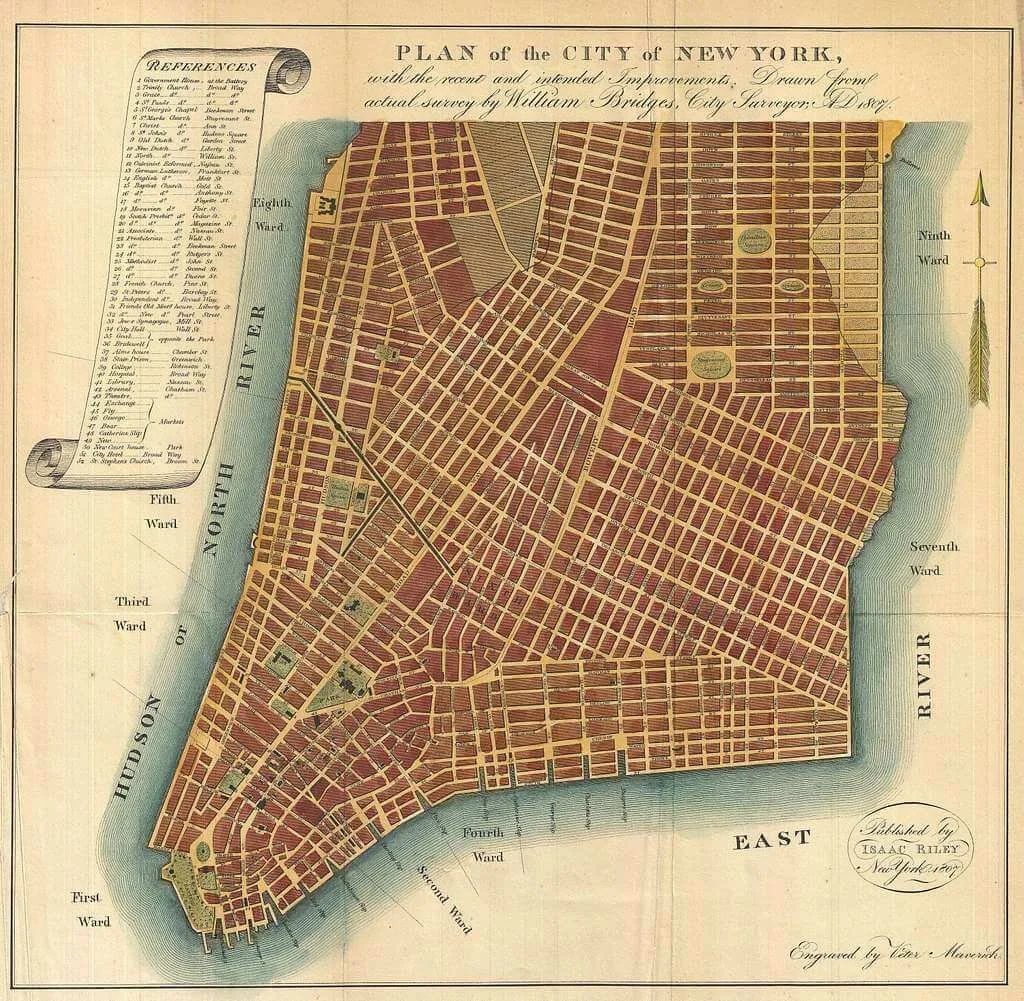

From the Archaic period to the Classical period, Greek cities developed towards clearer street systems and planned public centers. Consider the “Hippodamian” grid: orthogonal blocks, predictable intersections, and—most importantly—a central public square for gathering and trade.

Orthogonal grids existed before, but Greek writers indicate that it was Hippodamus of Miletus who codified this urban logic and applied it to places like Piraeus and (probably) Thurii. The grid was not an aesthetic fad; it was a tool for organizing civic life around an accessible center. The agora formed the basis of this order.

- Priene (4th century BC) is the most typical example of this: a city built on a mountainside in a rational grid pattern, with the agora at the center of the composition, surrounded by public buildings and streets intersecting at right angles. Because of this clarity, urban planning historians still use Priene as the “standard” Hippodamian city.

- Piraeus (5th century BC) was redesigned with a grid connecting the port, city gates, and main roads, along with a central agora. This was a method of directing the flow of people and goods into the public space.

The central agora, located “where the city meets itself,” was easy to find. The court, council chamber, market, and gossip spots were all within a short walking distance. Contemporary master plans often mimic grid geometry but forget the social engine at its center. If we copy streets without restoring the mixed-use, mixed-class purposes of the civic square, we end up with a traffic logic devoid of public life.

Agora as a Civic and Social Center

The Greek word agorá refers to both the “assembly” and the place where the assembly meets; the people and the place.birleştiren bir dil. Uygulamada agora, siyasi müzakereler, gayri resmi tartışmalar, mahkemeler, kurban törenleri ve alaylar, perakende satış, felsefe dersleri ve günlük yaşamın tüm hareketliliğine ev sahipliği yapıyordu. Açık, geçirgen ve okunaklı bir yerdi. 1931’den beri kazı çalışmaları yapılan Atina Agorası, iş, siyaset ve hukukun tek bir erişilebilir alanda iç içe geçtiği en net örnektir.

On a typical day in Athens, you could see merchants under the long-columned galleries, plaintiffs going to court, assembly members entering the assembly building, craftsmen selling tools, and philosophers drawing small groups of listeners. Religious calendars structured the year with sacrificial ceremonies and processions passing through the square. The Agora functioned because it allowed different activities to safely overlap in full view of the public.

Modern cities attempt to compartmentalize these energies: retail sales move to shopping malls, justice to isolated courthouses, politics to fenced-off squares, and social life to “privately owned public spaces.” This fragmentation weakens the feedback loops that once enabled citizens to feel a sense of belonging to their cities. The lesson of the agora is not nostalgia, but a programmatic mix of walkable daylight where disagreements, commerce, and celebrations are visible and close at hand. The example of Athens shows that this proximity is not chaos, but a spatialized constitution.

Architectural Typologies Within the Agora

The agora was not an empty space; it consisted of a series of elements that made public life sustainable. The most important of these were:

- Stoa (portico): long, roofed, columned galleries providing shade and shelter from the rain for shops, promenades, and gatherings.

- Bouleuterion: a roofed council building for the city’s boulē (council).

- Tholos & Prytaneion: the circular tholos that fed and housed rotating civil officials, and the prytaneion associated with the city’s sacred hearth and executive functions.

Together, these moderated the climate, framed movement, and gave institutions a visible address in the marketplace.

How types work (with examples).

- Stoas as climate and trade machines. The Stoa of Attalos in Athens created rentable rooms by combining a double-columned gallery with a spine of shops, turning the building into a commercial engine for 400 years. Many historians liken it to early shopping malls: its weather-protected edges extended the square’s usability in hot or rainy weather.

- The council that gathered in public view. The Bouleuterion provided an official, roofed room for debating budgets, treaties, and regulations; most Greek poleis had one. In Ephesus, the theater-like seating arrangement of the bouleuterion points to the performative dimension of civic discourse. This type of arrangement enabled institutionalized debate without removing it from the sphere of influence of the agora.

- Continuous administration. The Tholos, a small round building near the council complex in Athens, housed the officials in office, ensuring that the core of the administration was always ready, nourished, and accessible. This round, modest room was the beating heart of administrative continuity.

What do these types teach us about contemporary design?

- Edges matter. Stoas demonstrate how generous, shaded edges enhance public life; they recommend arched passageways, deep canopies, and columned facades for hot or rainy climates.

- Position institutions in the public square. The Bouleuterion logic advocates for visible council chambers and transparent municipal buildings—that is, a governance model that is walkable and spatially connected through daily interactions.

- Design for continuity. The functions of the tholos/prytaneion remind us that cities need small, always-open civic rooms for officials, ombudsmen, or mediators, located in places where people already gather.

The Architectural Language of Gathering

Ratios and Spatial Hierarchies

Excellent gathering spaces are understandable because they are composed of interlocking scales: corners within rooms, rooms opening onto courtyards, courtyards opening onto streets, streets opening onto squares. Christopher Alexander called this the open space hierarchy: people feel comfortable when they have a “back” (a refuge) and a wider view (perspective). This simple logic of back and view explains why edges and thresholds are so appealing.

The geometry of streets and squares can predict where people naturally flow and where they pause. Space Syntax research shows that certain configurations create “natural movement” without signs or programming, and concentrate paths (and thus chance encounters). If you want dialogue, make sure movement flows through the network, not around it.

Human-scale proportions are important. Alexander’s “Small Public Squares” model argues that excessively large spaces feel empty; narrower cross-sections make it easier to see faces, hear voices, and feel like part of a scene. Designers can combine longer axes for parades or markets with a modestly scaled “heart.” The place where you gather is small; the place where you walk is long.

- William H. Whyte’s field research revealed that edges, steps, and projections encourage sitting; people cluster in places that offer them places and options to lean their backs against. Movable chairs multiply micro-hierarchies in seconds.

- Recent AI-powered research confirms Whyte’s views: We now walk faster and spend less time in many cities; designs that offer rest stops, shade, and opportunities for conversation can reverse this trend.

Importance and Sensory Experience

Gathering is a multi-sensory experience. Materials convey warmth, texture, sound, and scent; they “speak” to the body before any sign. Juhani Pallasmaa argues that architecture is perceived through the eyes, ears, skin, and memory. Stone is permanent, wood is warm, and textiles soften sound. Designing for the senses is not a luxury; it makes people feel welcome.

Social factors such as sound, light, and comfort.

- Acoustics. When background noise is very high, people stop talking or leave. The WHO’s Environmental Noise Guidelines set targets that protect health. Use these targets to size absorption, green belts, and water features to mask loud sounds.

- Daylight. EN 17037 redefines daylight quality for indoor spaces and common areas (availability, view to the outside, exposure to sunlight, glare). In forums, libraries, and dining halls, balanced daylight that controls glare allows people to stay longer and remain calmer.

- Multisensory design. Cognitive research shows that richer sensory cues are associated with stronger place attachment; consider elements such as fragrant plants, tactile handrails, echoing wooden ceilings, and paving stones that resonate with footsteps.

Applications.

- Edges suitable for conversation. Use wood or textured stone on seating ledges; add soft, sound-absorbing ceilings under canopies so small groups can hear each other. (Whyte’s observation: people sit where they find a place to sit.)

- Comfortable microclimates. Combine shade, dappled light, and seasonal sun pockets instead of uniform exposure; EN 17037’s sunlight and glare controls help you adjust this mix.

Design as a Framework for Dialogue

A good public space does not eliminate disagreements; rather, it hosts them. Chantal Mouffe’s concept of the agonistic public sphere defines the public sphere as a place where different perspectives come together without requiring perfect agreement. The designer’s role is to make this encounter possible, safe, and understandable.

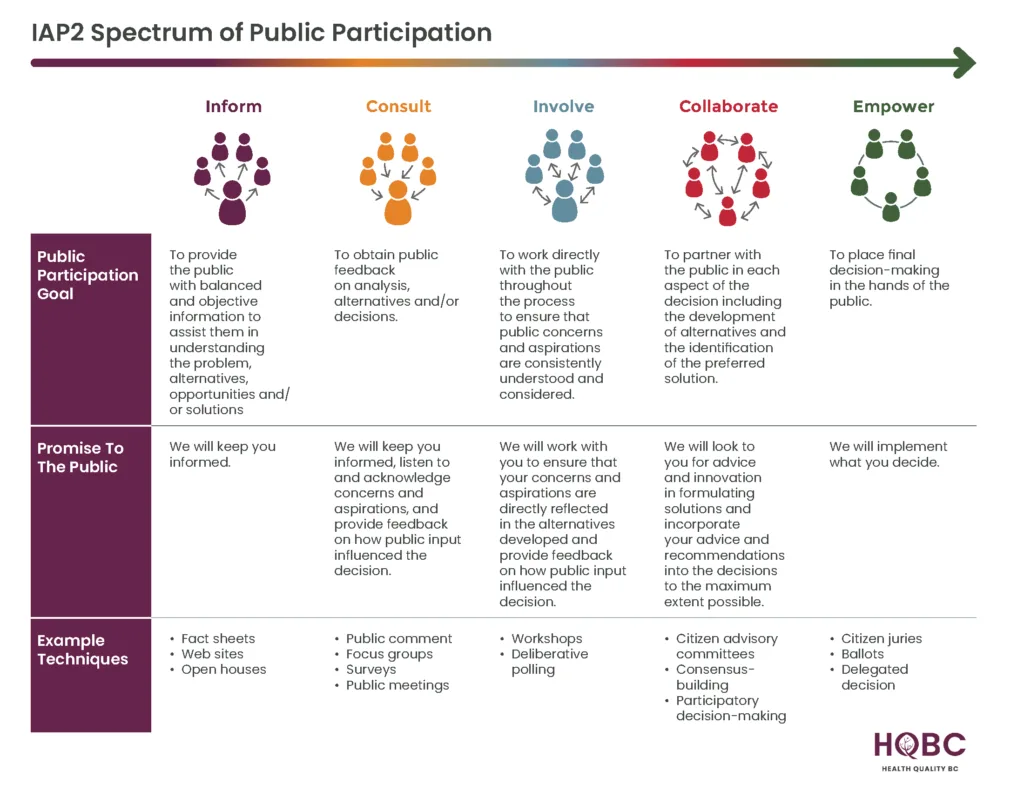

Use clear participation levels to determine the form of public participation. From “information” and “consultation” to “collaboration” and “empowerment.” Arnstein’s Ladder reminds us that symbolic workshops are not the same as joint decision-making; the IAP2 Spectrum translates this idea into practical project commitments. Include your level of participation in the summary, timeline, and budget.

Design moves that spark conversations.

- Triangulation. Provide external stimuli (games, art, vendors, performances) that will give foreigners something to talk about. Arrange the seating accordingly so that spectators can watch and participate.

- The integration of governance with the program is demonstrated. Place community rooms, service counters, or mediation desks at active edges; this promotes transparency and accountability (a lesson echoed by Whyte and place-making practices).

Case studies.

- Superkilen, Copenhagen. A participatory park that brings together objects and ideas suggested by residents from many countries, transforming its design into an ongoing cultural dialogue. The process, consisting of numerous public contributions and curated collaborative design, has made this space understandable for its users.

- Barcelona Superblocks. Reallocating street space to people created space for neighborhood dialogue, play, and activities; it also highlights lessons in evaluation, participation, and governance, as well as environmental and health benefits.

- Medellín’s social urbanism approach. Library parks and small “urban acupuncture” projects combined distinguished architecture with deep social participation by using design as a platform for new civic relationships.

What replaced Gora, and what was the cost?

The Rise of Shopping Malls and Plazas

Post-war North America replaced the open, civil complexity of the agora with enclosed shopping malls and specially negotiated “public” squares. Victor Gruen, who invented the modern shopping mall, envisioned walkable, mixed-use city centers, but later rejected what developers built, arguing that they preserved the profitable parts and abandoned the social ones. Meanwhile, in cities like New York, zoning plans enacted in 1961 created “bonus” plazas, or Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS). In these areas, extra building rights were traded for on-site public access. These two models became the dominant successors to the agora in suburbs and city centers.

Shopping centers combined climate, retail, and security elements indoors; festival markets (Faneuil/Quincy Market, Harborplace) added entertainment and tourism to this mix, but remained consumption-focused. In densely populated centers, POPS created forecourts, atriums, and pocket parks attached to office towers. Most of these were designed inspired by Whyte’s research on the factors that make small urban spaces successful, but they often underperformed when owners restricted seating areas, shaded areas, or operating hours. Cities later tightened the rules with necessary signage and clearer obligations.

Enclosure and private management have increased comfort and safety for shoppers and office workers, but they have narrowed the scope of permitted activities. A plaza or shopping center can feel open to the public, but it can be operated according to private rules; this is good for predictable commerce, but bad for serendipity and dissent. Occupy Wall Street’s choice of Zuccotti Park (a 24/7 open POPS) demonstrates the opportunities offered by such hybrid structures and the fragility of the rights within them.

The Loss of Democratic Spatial Practice

Democratic life depends on the ability to assemble, petition, and debate in designated areas. In privately owned spaces, freedom of expression is subject to judicial authority: In the case of Pruneyard v. Robins (1980), the California constitution protects certain freedom of expression rights in shopping malls, but federal law does not require other states to do the same. In many cities, public open spaces and plazas under property management can restrict protesting, distributing flyers, and even taking photographs through house rules and security protocols.

Research conducted in London revealed the proliferation of so-called public land with opaque ownership and restrictive behavioral rules; the use of a facial recognition system at King’s Cross property drew public backlash and the system was removed. The New York Comptroller found that more than half of POPS failed to provide necessary public services or access, leading to reforms such as mandatory “Open to the Public” signs and clearer enforcement. These are not abstract administrative oddities, but the practical limits of citizenship.

Permissions can be unilaterally changed by their owners, so democratic uses remain uncertain. London requires new spaces to comply with inclusive principles through the Public London Charter; in New York, similar transparency, labeling, and penalties aim to bring private management in line with public expectations, but these are ongoing projects, not resolved issues.

Architectural Sterility in Public Spaces

Areas where risk management is implemented are generally shifting towards a “clean but quiet” environment. Hostile or defensive designs—such as benches that prevent sleeping, sharp-edged nails, and furniture that controls posture—indicate who belongs and who does not, weakening the social mix that makes public life interesting (and fair). Research and advocacy reports link such measures to the exclusion of homeless and vulnerable individuals and a broader decline in well-being.

Beyond the visible infrastructure, rules and regulations that prevent loitering, busking, begging, or children playing may contribute to this. Academics have documented how physical design, behavioral rules, and content controls combine to hinder spontaneous use, particularly in POPS and secure zones. The result is a photogenic but socially flat landscape.

Transparent, rights-based governance (public regulations and on-site signage) and Whyte-style core elements (shade, seating-friendly edges, and movable chairs) reliably increase dwell time and conversation. Combine these with inclusive management (transparent working hours, minimal restrictions, accountable staff), and you get spaces that host both disagreements and pleasant moments: less museum, more meeting place.

Lessons Learned from Lost Places

Urban Memory and Erasure

Cities lose not only their buildings; they also lose the scenarios of public life. When an important place disappears, collective memory weakens and the city’s “visibility” (the mental map that helps citizens direct meaning and interpretation) is disrupted. Kevin Lynch has shown how roads, boundaries, districts, nodes, and landmark buildings shape a city’s identity; the removal of these landmarks disrupts this legibility.

The demolition of Penn Station between 1963 and 1968 serves as the best lesson in this regard: This outrage led to the creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Law in 1965 and a national preservation movement. This proves that demolition can trigger a new awareness of preservation, but that this is only possible after damage has been done.

Dolores Hayden adds that memory is not only monumental but also a social element. Urban landscapes often contain the history of the working class, women, and minorities, who are usually the first to disappear under the guise of “renewal.” Designing for memory means making these stories visible not only in museums but also in everyday city life.

Case studies.

- Les Halles, Paris. Demolished in 1971-72, “the belly of Paris” was replaced by a transportation/shopping complex that many considered ill-intentioned; however, decades later, the city reinvested to heal this wound. The lesson to be learned here: market halls are not just shacks, they are urban infrastructure.

- Scollay Square → Boston Government Center. As part of an urban renewal project, hundreds of buildings were demolished and thousands of people were displaced, thus rewriting memory as “decay.” Today, archives and local historians are working to recover the past that the square swept away.

Use UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach: inventory tangible and intangible layers, involve communities early in the process, and manage change rather than freeze it. HUL redefines conservation not as nostalgia, but as a living practice based on values.

Failure in Remake Attempts

Many “renovations” mimic old forms but overlook old functions. Festival markets and lifestyle districts often borrow the appearance of civic markets or squares, but they center on consumption and private control, creating what critics call “Disneyfication”: safe, simplified, standardized versions of public life.

Case studies.

- South Street Seaport, NYC. Decades of rebranding efforts attempted to transform a historic port into a festival shopping center. Despite the new architecture, observers still speak of a “chronic feeling that it’s not real.” This is a cautionary tale showing how important authenticity is without daily use and affordable rentals.

- The Humboldt Forum in Berlin (rebuilt palace). A meticulous Baroque structure with modern interiors sparked intense debate: Does the reconstruction of the Prussian façade honor or whitewash history? Critics point to donor policies and colonial collections that contradict the project’s stated mission.

- Rebuilding types versus rebuilding life. Even successful reconstruction projects (such as the Attalos Stoa, rebuilt as an agora museum) reveal the limits of copying hardware: you can rebuild the colonnaded gallery, but you cannot automatically rebuild the social software that once operated beneath it.

Measure “authenticity” through diversity of use, permeability, and governance. If a square can host protests, games, merchants, the elderly, and the young without special permission, and if lease agreements, working hours, and rules support this mix, then you are rebuilding not just its appearance, but the function of an agora. (Whyte’s observation book remains a practical checklist: seating-friendly edges, shade, food, and freedom to linger.)

Architectural Nostalgia and Critical Conservation

Conservation theory distinguishes between emotional value and semantic value. The Venice Charter (1964) emphasizes originality, minimal assumptions, and distinguishable additions; these are protective measures against romantic pastiche. The Nara Document (1994) broadens authenticity to include various cultural contexts. The Burra Charter functionalizes a values-based process for managing change. Together, these documents advocate for accuracy and transparency rather than replication.

Application spectrum (with examples).

- Reconstruction (rare, controversial). The palace in Berlin shows how copies can fuel memory politics; proceed only with full documentation, open debate, and honesty about innovations.

- Adaptive reuse (usually the best option). The legal rescue of Grand Central (1978) and its subsequent restoration set a precedent: keeping the building in public use rather than turning it into a stage set. The opposite example is Penn Station; the loss of this building still shapes policy and current redesign debates.

- Urban restoration. Sometimes the lesson is to undo the “change”: Seoul restored the Cheonggyecheon Stream by removing a highway, regaining climate comfort, biodiversity, and public space and the memory of the city’s hydrology.

Before choosing one of the options to copy, reuse, or remove, ask yourself these questions: (1) What are the values that make this place important (not the atmosphere)? (2) Can the governance model ensure daily and democratic use? (3) Will the changes clarify the original and the new, or will they cause confusion? The Venice/Nara/Burra guidelines establish ethical rules; the HUL process establishes procedures; your summary should translate both into design constraints that the public can read on site.

Can We Design New Agoras Today?

Gaining Space for Civic Participation

Cities do not need marble columns to regain the energy of the agora; they need reliable streets and squares as daily gathering places. Proven, low-cost tactics include open street programs (weekly car-free corridors) and tactical squares/parks (quickly installed seating areas, shade structures, and plants). Bogotá’s 127 km Ciclovía program demonstrates the social potential of recurring street closures. 1.5 million people use this program weekly, and its social and health benefits are documented, with similar programs implemented worldwide. Case studies from San Francisco’s Parklet Handbook and the Global Street Design Guide clearly outline simple, public-priority rules (universal access, no exclusive use) that any city can adopt.

To prevent the situation of “suddenly appearing and then disappearing,” combine trials into laws. Milan’s Piazze Aperte program uses tactical urbanism as an official city-wide method: it experiments with quickly transforming sidewalks into squares, then makes the successful ones permanent. Independent reviews and design guidelines document the results (safer crossings, longer dwell times) and the scaling process.

Design works when rules are applied. London’s Public London Charter document establishes clear, rights-based principles for new public spaces (signage, inclusive access, transparent management) and links them to planning approvals. New York City’s POPS standards similarly require legible signage, necessary amenities, and enforceable obligations, so that “privately owned public spaces” behave more like true public spaces. Include these governance requirements in your summary from day one.

Hybrid Typologies for the 21st Century

The most compelling “new agoras” bring together a library, maker space, event hall, and city services under one roof. Helsinki’s Oodi describes itself as a “living meeting place” and offers everything from studios to 3D printers, cinemas to community rooms. It is designed for spending time, not rushing. Aarhus’ Dokk1 houses the main library alongside citizen services (including national ID/CPR support), making daily bureaucracy part of civic life. Awards and news stories highlight how these buildings support not only collections but also daily gatherings.

Another hybrid example is the Resilience Hub: a community facility equipped for use in good times (classes, charging, Wi-Fi, meetings) and crises (electricity, cooling, communication). The Urban Sustainability Directors Network guide details how centers will be financed, programmed, and co-managed to build local capacity and trust, the fundamental components of a modern agora.

Democratic use scales when assemblies in space connect with online assemblies. Born in Barcelona, Decidim is an open-source infrastructure designed to be compatible with in-person meetings, enabling proposals, assemblies, participatory budgeting, and feedback. Matching a town square (or library hall) with a Decidim instance allows people who come in to continue shaping decisions after they go home, and vice versa.

Architects as Cultural Mediators

Use the IAP2 Spectrum to clearly define the promise of participation “from information to empowerment” and ensure that the project’s scope, schedule, and budget are consistent with this promise. Use Arnstein’s Ladder to control power sensibly: are participants merely being consulted, or are they sharing control? Specify the level in public documents so that communities can hold teams accountable.

Evaluate social outcomes as design outputs. The RIBA Social Value Toolkit provides practical methods for demonstrating changes in welfare, social cohesion, and accessibility. These metrics can be tracked by clients and municipalities alongside cost and energy. Publishing this data (pre- and post-use) transforms the new agora from a concept into a public asset with demonstrable performance.

In the context of cultural heritage, strike a balance between change and cultural continuity using UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape approach; map tangible and intangible values before defining boundaries. When questions of representation arise, rely on the principles of Design Justice: center those most affected in goal setting and governance, and ensure they participate in workshops. This means negotiating culture rather than merely shaping it.

Reflections on the Role of the Architect

Structure for Permanence and Transition

Designing for both “forever” and “next year” at the same time is a real skill. Two useful perspectives: (1) The idea of cutting layers (site, structure, facade, services, floor plan, furnishings) reminds us that different parts of a building change at different speeds, so we should protect the slow-changing ones and make the fast-changing ones easily replaceable; and (2) open building, which separates long-lasting “supports” from short-lived “fillers,” giving users the power to reshape the space over time. Together, these point to an ethical rule: permanence in the skeleton, flexibility in the organs.

From ethics to standards.

If you want adaptability to survive budgets and revenues, code it. ISO 20887 defines design principles for disassembly and adaptability; the circular economy guide encourages the pre-documentation of materials (e.g., with material passports) so that future teams can reuse, exchange, or recycle them at high value. In practice, this means reversible connections, accessible service areas, standard modules, and a live inventory of what’s inside your building.

Adaptive reuse is generally more carbon-efficient than new construction because you preserve the carbon emissions you’ve already “paid for.” Research and case studies (such as Arup’s office-residential analysis and the One Triton Square renovation project in London) show that converting or renovating instead of demolishing results in significant carbon emission savings. The Circular Buildings Guide adds: build only what is necessary, build for long-term value, and choose the right materials.

Concretizing Values Through Forms

If you believe in honor, warmth, and hospitality, people should feel these values with their entire being. In Juhani Pallasmaa’s work on multi-sensory architecture, it is argued that sound, warmth, texture, and scent are as formative as sight. Design choices such as wood ceilings that soften acoustics, stones that provide coolness, and railings that invite touch transform abstract values into everyday experience.

Accessibility is not an additional feature; it is a value expressed in the plan, section, and interface. The Seven Principles of Universal Design (equal use, flexibility, simple/intuitive use, perceptible information, error tolerance, low physical effort, appropriate size/space) provide a checklist written in plain language that you can use when making every decision, from door hardware to wayfinding and seat heights.

Venturi and Scott Brown’s work, “Duck and the Decorated Shack,” reminds us that buildings sometimes communicate as symbols, and sometimes by containing symbols (signs, art, programs). Choose the right method for the subject, so that people can understand what a place represents without needing a guide. What matters is not irony, but meaning that is readable in everyday life.

Value-driven form also stems from who shapes it. The Design Justice framework requires designers to center the communities most affected by a project and to share power throughout the process, not just consult at the end. To ensure this commitment lasts beyond a single meeting, incorporate it into the summary and governance.

Designing Places to Remember

Cities are remembered through form and use. Kevin Lynch’s work on visibility explains how roads, edges, districts, nodes, and symbolic structures help people organize meaning; Aldo Rossi adds that permanent urban works/monuments fix collective memory over time. Dolores Hayden broadens the perspective to include not only large monuments but also the everyday, lesser-known histories within the landscape. Good “memory design” balances legibility, permanence, and inclusivity.

Memory does not have to be monumental. Germany’s counter-monuments encourage reflection by subverting the traditional notion of heroism; Stolpersteine (“stumbling stones”) transform sidewalks into networks of remembrance by placing names on doorsteps. These micro-actions are powerful precisely because they exist within, not outside, daily routes.

Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial demonstrates how restraint can deepen remembrance: two black granite walls etched into the ground, names inscribed in chronological order, and a reflective surface that merges the visitor’s image with those who died, creating a personal and communal encounter without imposing a single narrative. The monument’s design required it to be an apolitical, contemplative work listing every name; the design met and conveyed these conditions.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.