How does space transform into form in Zen architecture?

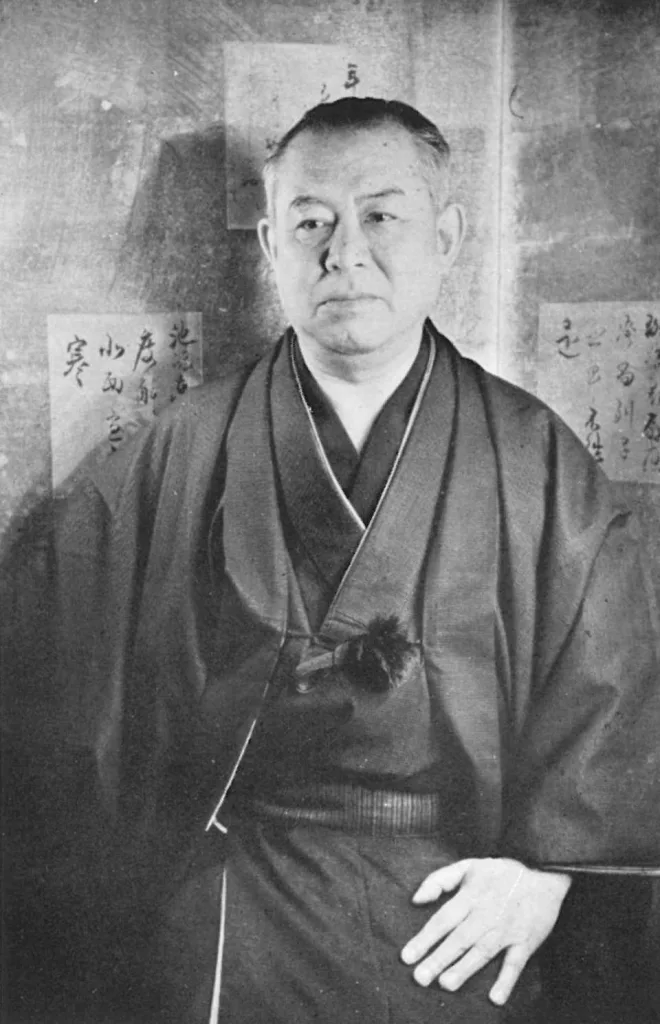

Zen architecture emphasizes ma’ (間) – not just empty space, but a meaningful spatial pause. Gunter Nitschke states that in order for us to truly experience emptiness, we need “an extremely sophisticated environment of form and formlessness.” In other words, Japanese architects treat space not as absence but as active content. In practice, this manifests as the engawa, a narrow wooden corridor that blurs the boundaries between interior and exterior space. The engawa serves as a liminal threshold: a framed void through which light and air flow, inviting one to pause. As Jun’ichirō Tanizaki observed, “an empty space is marked by flat wood and flat walls, so that the light drawn into it creates soft shadows within the void.” In such pavilions and verandas, minimal structure enhances subtle shadow play and silence.

Traditional sites such as Tōfuku-ji and Ryoan-ji embody this philosophy. In the gardens of Tōfuku-ji’s Hojo (abbot’s quarters), designer Shigemori Mirei of the 1930s placed simple rocks and raked gravel side by side on either side of the hall. These four dry gardens define the space with things that are not there, mixing cubist geometry with natural images (square “cubes” of sand next to moss-covered stones). The resulting emptiness is not sparse, but highly structured: each garden invites contemplation through absence. Similarly, the famous Ryoan-ji rock garden in Kyoto is “so confusing” that a computer analysis found that its empty pebbles evoke the “outline of a branching tree” that is invisible to the conscious eye: “What you should respond to is not the objects, but the empty space.” At Ryoan-ji, fifteen stones merely suggest distant mountains; our eyes move freely within and beyond the bare gravel. Some scholars even note that this “central void” appears to shift as one moves along the veranda, imparting a dynamic life to the emptiness.

Shinto shrines also display purposeful emptiness. Take Ise Jingu: the inner sanctuary is located behind four fences, visible from a distance only as simple wooden roofs. Pilgrims are kept outside, feeling the absence of the kami (divine spirits). The architecture is pure and unadorned—wood and reeds rising on poles—so that the emptiness itself feels sacred. In fact, Zen and Shinto traditions converge in their celebration of nothingness. Zen monk Dōgen said that a cloud-like, formless wandering is ideal; similarly, Shinto masters teach that the essence of a shrine is “the emptiness in which people feel the presence of the gods.” (This idea has been noted in recent studies on the architectural philosophy of Ise.)

In contrast, Western architecture generally defines space through rigid enclosures, light-filled interiors, and decoration. Tanizaki noted that the beauty of Japanese design lies in shadows, contrasting the Western emphasis on light with the Japanese tendency to “plunge into darkness.” While Western eyes may focus on walls and objects, every beam and empty corner in Japanese alcoves speaks. This reversal—allowing the void itself to shape the experience—lies at the heart of Zen design. Here, emptiness is “not something seen, but something felt”: a silent invitation to perceive form through absence. In short, Japanese architects allow voids to define space as much as solids. And they hope we will find meaning in these voids.

Can architecture invite tranquility without using a single word?

In Zen-inspired buildings, the space itself choreographs silence and attention. The Katsura Imperial Villa (Kyoto, 17th century) exemplifies this concept. Its rooms are arranged in a whirling plan consisting of tatami-mat-floored shoin salons and tea houses with sliding shōji screens opening onto gardens. Movement in Katsura is deliberately slow: stepped stones and narrow verandas lead one past carefully framed views of moss, maple trees, and the river. Upon reaching a tea house, the mind is already calmed by the series of quiet, unpretentious spaces. As architect Bruno Taut marveled while living at Katsura, “Three days… it is architecture; three days later, it is poetry.”

Minimalism and nature at Katsura Villa. Wooden blinds and tatami floors frame the garden as a tranquil extension of the interior space.

The material palette reinforces the stillness. Plain wooden walls, paper screens, and cold stone echo in a quiet tone. Tanizaki praised this dim tranquility: “We surrender ourselves to the low light” and discover its unique beauty. In Katsura’s tea ceremony rooms and temples such as Daitoku-ji, even the smallest details—the rough texture of ink-stained plaster walls, the whisper of sliding doors, the occasional rustle of bamboo blinds—become focal points. The designers of these spaces deliberately eliminate distractions. There are no bright colors or clutter; instead, each element demands attention. The rock gardens themselves become tools for contemplation: the simple raked gravel at Ryoan-ji or Saiho-ji slows the eye and the breath. As National Geographic notes, a visitor “cannot take in Ryoan-ji in a ten-minute walk”—it takes hours of sitting in the garden until “the garden becomes a part of you.” In practice, entering a Zen garden or temple teaches visitors to stop and breathe: as they focus on moss, stones, and delicate light, “your pace slows, your heart calms, and your mind refreshes.”

Katsura’s strolling gardens and tea houses make this unspoken rule explicit. Each tea house is tucked away under pine trees, inviting tranquility. Even the act of entering the tea house is ritualized: guests pass through a low sliding door, bow at the threshold, and kneel on tatami mats that instantly slow and lower the body. The only decoration inside is a tokonoma alcove containing a single scroll or flower arrangement. This sparseness frames human presence as an offering in and of itself. In short, the architecture frames tranquility. It does not announce silence with signs—it builds it into the floors you walk on, the corridors you must bow to, and the simplicity you cannot ignore. In these spaces, sound is absorbed, movement is measured, and every breath becomes intentional.

- Enter respectfully, bowing your head, through a narrow doorway or nijiriguchi.

- Pay attention to the changing scenery as you slowly make your way along a veranda or stepped path.

- Once inside, sit down so that you can see only the parchment or ikebana in the tokonoma.

- Adopt humility and consciously position your hands and feet.

Each of these steps is embedded in the architecture. Without saying a word, the space teaches visitors to pay attention. Here, stillness is not just silence; it is a mindful presence. It is the restraint of a temple’s body, allowing the mind to wander inward—which is also the purpose behind Zen gardens and tea rooms.

How does light voids emerge in Zen-inspired design?

Light is the sculptor of space. In Zen structures, daylight and shadow interact to define space. Tadao Ando’s famous Light Church (Osaka, 1989) vividly illustrates this lesson. Ando cut a cross-shaped slit in the end wall of a closed concrete box. When sunlight enters, light itself becomes architecture: a shining cross moving along the walls and floor. The heavy concrete then acts as a canvas, illuminating the empty space around the cross. As Ando puts it, “light is an important controlling factor”—by creating spaces for light, he creates “a place for the individual, a region within society.” The effect is profound: where Western churches rely on ornamentation, here the spiritual emerges from the pure contrast of emptiness and light.

Ando’s Church of Light (Osaka): A cross-shaped opening lets in a beam of sunlight that enlivens the simple concrete interior.

This interaction—kage (陰, shadow)—has a deep cultural resonance. As Tanizaki observed in a Japanese alcove, the dim shadows in an empty corner can evoke a sense of “complete and absolute silence.” In the Zen context, shadows are not flaws but essences—they add depth and mystery to spaces. Even in dry gardens, the low morning light casts long, angled shadows on stones, transforming an empty sand field into a landscape. In the afternoon sun, a rock facing west may glow warmly, but in twilight it blends into uncertainty—each hour revealing a new face of emptiness. As National Geographic notes, a Zen garden truly opens up only when you “fully absorb the scene, when the distinction between the outer garden and the inner garden disappears”—an experience of light and shadow that unites us with emptiness.

Zen-inspired modern spaces continue this tradition. For example, in Kengo Kuma’s GC Prostho Museum (Aichi, 2010), light filters through slatted wooden panels in a way that evokes rice paper lanterns. Natural light enters delicately, transforming the rooms into warm, glowing spaces during the day. Even the materials become lenses: semi-transparent washi paper walls diffuse light, so the rooms are never harshly lit, only softly enveloped. A diagram illustrating “layering” can be imagined—the sun passes through pine needles, open eaves, then is filtered again by shōji. In all these cases, the architecture itself is framed by light paths. The Western focus on rigid forms (columns, walls) is reversed: here, it is the material, revealed by the movement of the sun, that defines the spaces and gaps.

All these moments are fleeting. The morning light brings a pale calm; the midday sun can erase shadows, and twilight turns the walls flat gray. However, in Zen design, this temporality is intentional. The same courtyard has completely different moods at dawn and dusk, and each one reveals the emptiness anew. As Ando himself put it, “Light is not just a design element; it is a material.” Architecture inspired by Zen shapes space with light, ensuring that emptiness is never static: dawn, shadow, and twilight form a living rhythm.

What is the role of ritual and restriction in Zen spatial practice?

Zen spaces typically serve special rituals that require humility and focus. The most famous of these is the tea ceremony (chaji), which consists of a series of strictly controlled movements. Guests pass through a nijiriguchi (sliding door) and remove their shoes, bowing as a physical reminder of humility. Upon entering the tea house, they kneel and gaze at the tokonoma alcove, where the host has placed a single scroll or flower. This empty corner—devoid of excess—is the focal point of the ceremony. Even its name is measured: tokonoma simply means “floor space” and underscores its emptiness. The guest’s gaze is drawn to this empty frame.

Within the fixed dimensions of the tea room (usually 4.5 tatami mats), every step is carefully arranged. A service sequence might be as follows: (1) enter and greet, (2) sit facing the tokonoma, (3) watch the host prepare the tea, (4) drink in silence, (5) examine the vessels, and (6) depart. This choreography is written into the architecture itself. Low ceilings encourage intimacy; wooden floors creak softly; a single niche demands attention.

Even the tea service is performed slowly and deliberately, echoing the slowness of the house. Japanese architects embrace this constraint as a design principle: Junya Ishigami’s small chapel in Shandong and Tezuka Architects’ simple wooden church use minimal frames to frame the people and rituals within.

The entrance to the tea house at Daitoku-ji (nijiriguchi): a low door forces visitors to bow and enter modestly. Inside, a single scroll or ikebana arrangement fills the tokonoma alcove, emphasizing emptiness and focus.

Lesson: discipline as a formative force. By limiting stimuli—through compression, kneeling, and closure—space directs energy inward. In a tatami room, there is “nothing else” but the play of light and shadow around the alcove; the only sound may be the rustling of bamboo outside. In this simple backdrop, even a bow or a shared cup of tea takes on deeper meaning. Kengo Kuma once noted that the beauty of such environments stems from intentionally leaving the space empty. This architectural “empty kotatsu” ensures that every chosen object (a scroll, a kitchen utensil) feels significant.

The basic spatial elements of Zen ritual spaces are as follows:

- Tokonoma (alcove): The sole decorative focal point, always facing guests. The space, usually illuminated by a single sconce or an open window, invites introspection.

- Nijiriguchi (entrance): This low and narrow entrance forces visitors to abandon their status and pride. This act of bowing aligns visitors’ posture with respect.

- Compression and expansion: Many tea paths narrow (forcing the person to pause) and then open up to a natural garden landscape (rewarding stillness with beauty). This ebb and flow slows down the body and mind.

Can Emptiness Shape the Future of Architecture in a Crowded World?

In rapidly urbanizing Japan, Zen principles are finding new life. Atelier Bow-Wow’s micro-scale “pet architecture” adapts unused urban corners into small homes, demonstrating that even a closet-sized dwelling can be meaningful when space is thoughtfully utilized. Muji’s experimental homes (by Shigeru Ban and others) embrace subtraction: rooms are simplified, often whitewashed and unheated, trusting that minimal design can be satisfying. This is yohaku no bi (余白の美), literally “the beauty of white space.” As academics have noted, yohaku-no-bi is an aesthetic of emptiness or “lessness”—a celebration of the unspoken or unwritten. In architecture, it means “luxury in emptiness”—a home where open floor space is as valuable as furniture.

Even a classic like Ando’s 1976 Azuma Row House in Osaka foreshadowed this. Ando built a single concrete volume on a narrow plot surrounded by neighboring walls, with no windows facing the street. Instead, he cut a void—an inner courtyard—right through the middle. This empty courtyard is the heart of the house: a sky-lit void that brings light, air, and life into the space. It transforms life not into claustrophobia but into a ritual of nature. It is no surprise that Ando said, “Architecture should remain silent and allow nature to speak…” Here, the void is also ecological: the house requires no air conditioning (it breathes naturally) and its minimal footprint wastes no floor space.

Looking ahead, these principles offer answers to issues of density and sustainability. In densely populated Tokyo, small urban shrines and pocket gardens have already begun to create “serene voids” among skyscrapers. Architects are reinterpreting less material with more meaning. High-tech roofs opening up to the sky (as seen in Kengo Kuma’s designs) or streets lined with temple miniatures remind city dwellers how to pause. Bow-Wow’s machines for living help us see Tokyo’s leftover land not as a lack but as valuable empty spaces. In this sense, Zen teaches eco-zen: living lightly on earth by simplifying and finding richness in simplicity.

The deepest experiences lie in the things that are hidden. An empty wall, a silent courtyard, a single lantern in the mist—these evoke a deeper resonance than any cluttered facade. The architecture of the future will embrace the art of emptiness, presenting “luxury” not as extravagance, but as a space for the mind and soul. This redefining of luxury and beauty (the beauty of empty space) is Japan’s gift to the cities of the future: less is not a lack, but a possibility.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.