This article is an independent version of the article featured in this issue of DOK Architecture Magazine. You can access the entire journal via this link:

A cathedral can be repaired, but how we choose to repair it reveals what we value. The fire at Notre Dame was as much a test of memory as it was of masonry.

On April 15, 2019, Notre Dame burned.

On December 8, 2024, it reopened, cleaned, rebuilt and rising again.

Between these dates lies a civic decision about memory. What to preserve, what to change,

and what that says about us.

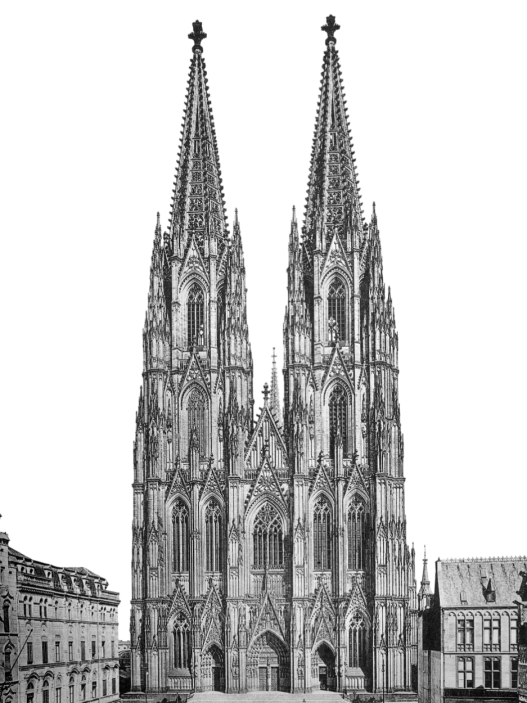

France restored the cathedral à l’identique, a near-twin of the prefire image, including Viollet-le-Duc’s 19th-century spire. This move privileges continuity of form over a visible collage of eras. It canonizes a specific moment in the building’s long life and asks us to accept that “sameness” is curated.

Not every layer gets an equal voice. It’s a defensible, public-spirited choice that protects the silhouette people carry in their heads, yet it reminds us that authenticity is edited, not absolute.

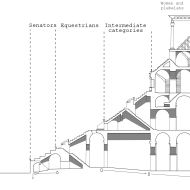

The rebuilding of the lost timber “forest” revived medieval carpentry on a national scale. About a thousand oaks, felled in a narrow winter window, seasoned and shaped by hand. It became a cultural act as much as a technical one, making a craft lineage tangible. It also raised ecological questions in a century defined by climate limits.

Lead presented a different dilemma. The original roof used hundreds of tons of it, as did the restoration, citing longevity and weathering performance. The health concerns are real, as are the mitigation measures. The lesson is broader than Notre Dame. IT shows that materials are never neutral to life.

They carry histories, risks, and responsibilities throughout their life cycle. When we inherit a historic palette, we also inherit the duty to model its impacts, enforce protections, and communicate them clearly.

Visitors will see oak beams, mortise and tenon joints, hand-hewn geometry, the visible work of carpenters.

They will not see the 21st-century operating system under the hood. Mist fire suppression hidden beneath the roof, dense sensor networks, phased stabilization strategies that secured cracked vaults and removed dangerous scaffolding before reassembly.

The 8,000-pipe organ was disassembled, decontaminated, and revoiced.

This is the new norm for living monuments. Restore what the public comes to see and upgrade what keeps it safe.

Notre Dame is government property, a functioning church, a world icon, a tourist magnet.After the fire, these roles were negotiated in the interior.

The result is restrained. Contemporary liturgical furnishings that defer to the Gothic space, clearer circulation, careful lighting, restored murals, and chapels that have returned to color.

It reads as stewardship.

Authorship here is plural. Church, state, city, and public, each giving a little, each keeping enough to recognize itself in the result.

Some argued for marking the trauma permanently with a charred beam, a memorial suture.

France chose continuity.

Let the fire live on in archives, exhibitions, and memory, rather than in deliberate scars on the nave.

With this neither path is neutral. Each proclaims values.

Paris chose resurrection and daily use over didactic ruin.

For many, this is its own form of healing.

The return of Notre Dame is more than a repair. It is a statement about what we honor. Form over collage, craft revived alongside code, materials carried with responsibility, authorship shared across institutions. In an age of anxiety, this restoration chooses legibility and service.A cathedral that feels the way people remember it, protected by systems they’ll never notice.

This is the balance we keep circling in this issue, curating experiences without freezing life, so that the places we inherit can continue to belong to the present.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.