Understanding the Meaning of Heritage in Architecture

Fame is fleeting. It feeds on headlines, museum openings, and glossy photos. Legacy, however, is enduring. It lives on in how a building is used decades later, how it adapts, and whether people still value it when no one is watching. Stewart Brand’s idea that “all buildings are guesses, and all guesses are wrong, so design for change” serves as a useful compass: If your work can learn and adapt, it has a chance to endure beyond your name. Legacy is what survives the initial wave of interest; it is the usefulness, care, and adaptability that become apparent over time.

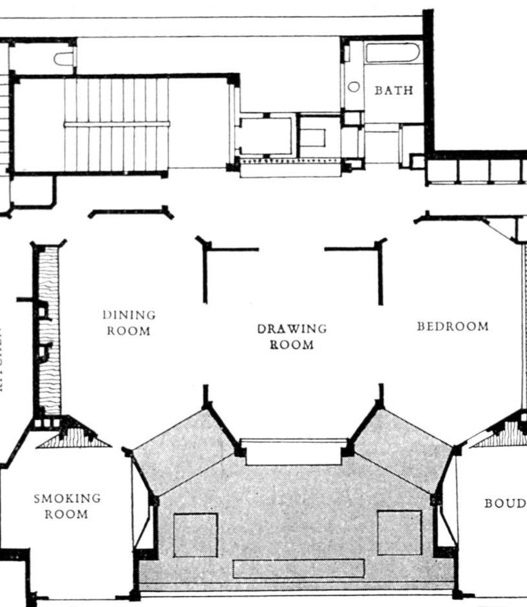

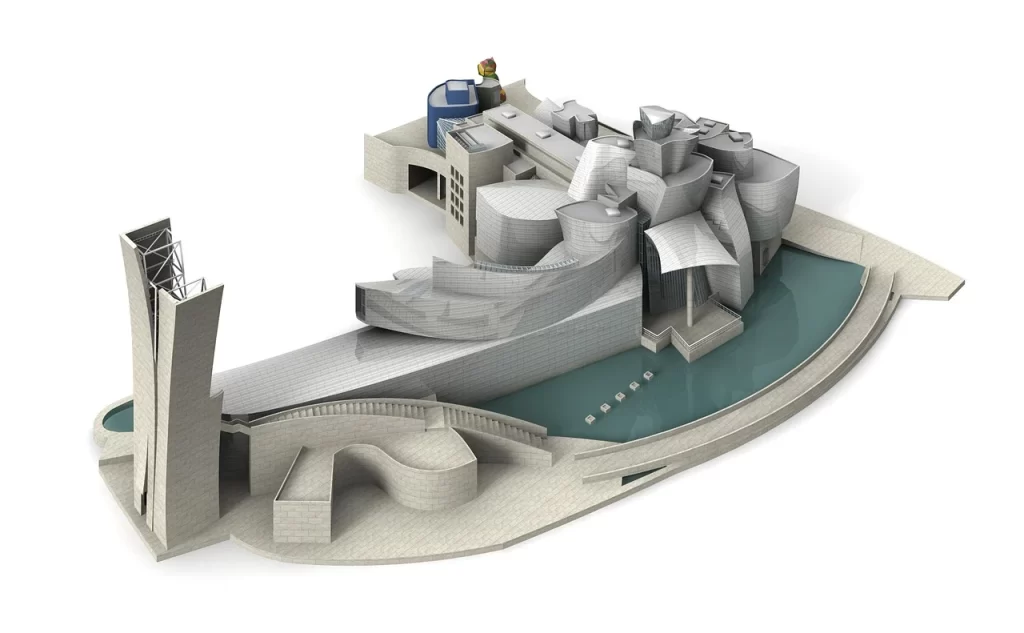

Consider the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. The “Bilbao effect” has become shorthand for how a stunning building can revitalize a city, but a longer-term view reveals a more complex story. Bilbao’s rise was achieved not through a single symbol, but through coordinated public investment, cultural programs, and urban renewal. The building’s fame helped, but the city’s coalition-building and policy infrastructure sustained the change. An ecosystem must exist around the legacy. Fame alone does not create an ecosystem.

How Can an Inheritance Outlive Its Creator?

Some projects continue to grow even after the architect has passed away. Sagrada Família, which began in 1882, continues to exist as a place of craftsmanship, dedication, and debate, with the main structure scheduled for completion a century after Gaudí’s death. This structure, now a civic project, is being built by generations of builders and citizens. The author may disappear, but the work remains, reevaluated every decade with fresh eyes and new needs. This is the moving legacy.

Other works have proven their longevity through maintenance and restoration efforts. Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute is valuable not only for its beauty but also because institutions have carried out careful conservation work. The teak window walls have been repaired and the concrete preserved, ensuring that the building continues to serve scientists. Here, heritage is manifested in the form of maintenance plans, budgets, and patient collaboration between architects and conservation experts. This is not a spectacular thing, but it is through such care that architecture can maintain its place in everyday life.

Architectural Symbols and Their Invisible Impact

Symbols shape silhouettes; invisible systems shape lives. Monumental buildings catch our attention, but most transformative architectural actions are hidden in pipes, codes, and standards. The sewer renovation project carried out in London in the 19th century following the “Great Stink” incident did not create a distinctive facade. Instead, it brought clean water, sewers, and a healthier city; an infrastructure legacy that London still relies on today. This story reminds us that the most powerful architecture often addresses a city’s body rather than its face.

Building codes are another silent revolution. Reforms such as New York’s 1901 Tenement House Act mandated standards for light, ventilation, health, and fire safety, reshaping the housing of millions. Modern regulations continue to evolve in response to tragedies and new knowledge, from cladding regulations introduced after deadly fires to debates about stairwells and natural light in mid-rise residential buildings. These rules rarely make headlines on social media, yet they determine how people live, sleep, and escape.

Time as the Ultimate Judge of Value

Time humbles even the most certain things. Some award-winning buildings face demolition within a few decades, raising tough questions about the cost of maintaining durability, adaptability, and enduring symbols. Brand’s framework helps here too: Buildings that embrace change—low-impact areas, flexible frameworks, honest materials—often age better than inflexible, perfect objects. In the long run, a building’s repairability and reinterpretability matter more than its original appearance.

History also changes our pantheon. Consider the Barcelona Pavilion: built in 1929, it was demolished shortly after, then rebuilt in 1986 after proving to have a longer lifespan than its first incarnation. Or consider how cities gradually embrace works that were once controversial as they become part of the local identity. Time does not merely judge; it sometimes revives and prompts us to recognize which forms are still necessary.

Personal and Collective Memory in Design

Designers bring their personal vision; spaces, however, hold collective memory. Sociologist Maurice Halbwachs argued that memory becomes enduring when it is tied to spatial environments such as streets, thresholds, and monuments that groups use to remember together. Pierre Nora called these connections “memory spaces”: places where a society stores the things it values when its living memory is erased. Architects, whether they want to or not, continue to incorporate these memory tools into everyday life.

Some are sincere and decentralized in structure, such as Stolpersteine. Stolpersteine are small brass stones placed on the sidewalks in front of the former homes of Holocaust victims, transforming an ordinary walk into an encounter with history. Others are civil and intellectual in nature, such as Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial. This memorial invites people to see themselves among the names and to engage in a quiet, physical act of remembrance. Both demonstrate how built form can quietly embody grief, honor, and continuity. Heritage lives there too, in the shared gestures that a place makes possible.

Basic concepts and real-life applications

If you want your work to be greater than your identity, design for change and care. Imagine the life after the photo shoot: Who will repair this door, who will oil this wood, how will the next generation make small changes without ruining the entire structure? Learn from the invisible successes of infrastructure and code: Sometimes the most human thing you can do is make a system a little clearer, a little safer, a little more lovable, and easier to maintain. And when you reach a symbolic form, aim for the permanence of memories rather than showiness. Help communities define themselves in what you do, every day, every decade.

Purposeful Design Beyond Ego

Intent in Architectural Narratives

Architecture gains meaning when it is about the story of a project, not the project’s creator, but the space where the project will be located and the people who will use that space. Phenomenology offers a useful compass in this regard: Juhani Pallasmaa reminds us that buildings are not only seen, but also felt, heard, and smelled; the narrative of a project should be a choreography of a complete sensory journey rather than a single image. When you start with the question, “How does this place feel at dawn in winter, at noon in summer, in the quiet of the weekday, or in the noise of the festival?”, you write a story that users can not only admire but also live within.

A place itself can be a hero. Christian Norberg-Schulz’s concept of “genius loci” defines design not as giving a place personality, but as revealing its character. If a riverside town desires shade, breeze, and public spaces, the narrative might focus on permeability and thresholds; if a hillside neighborhood needs protection from wind and bright light, the narrative might turn inward, with thicker walls and quiet courtyards carved out. What matters is intention: a clear line connecting climate, culture, and use, so that visitors can read the story without opening the monograph.

There is also a narrative to events. Bernard Tschumi argues that space and event are inseparable; the meaning of a building emerges from the events that take place within it. Designing from this perspective directs one toward staging daily rituals: entrances where people slow down to greet each other, inviting landings for taking breaks, rooms where the acoustics are tuned for conversation… Thus, the story of a space is written over time by its users.

Serving People and Influencing Peers

The quickest way to fall into the ego trap is to design with the photo in mind rather than daily use. A practical solution is to focus on measurable outcomes from the outset: comfort, satisfaction, energy during use. The UK’s Soft Landings framework and post-occupancy evaluation culture were created for this purpose. This framework encourages teams to carefully plan delivery, build close relationships with users, and test whether the building works as promised. When feedback loops and user surveys (such as the BUS Methodology) are integrated into the system, applause gives way to evidence, and you begin to move towards people’s real needs.

Operational ratings make this philosophy visible. NABERS UK’s Design for Performance approach shifts the focus from predicted models to real energy results that you can verify each season. When the customer sees the star rating based on a year’s worth of measurement data, the conversation changes: facade choices, controls, and services become tools not for achieving dramatic gains, but for providing people with affordable and comfortable services. Beauty still matters, but it is grounded in the integrity of functional spaces.

If you want a simple rule, it is this: make fewer promises, measure more, and allow users’ experiences to be the important evaluation. British “Probe” studies and decades of POE literature show that buildings improve when designers listen to users’ opinions after opening day. Small changes that aren’t trending on social media but transform daily life inside the building, such as adjusting ventilation rates, regulating lighting, and improving wayfinding systems.

Resisting the Trap of Signature Style

A recognizable style is not an inheritance; it is a risk. This discipline has long warned against creating icons for the sake of icons. Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour’s work on “ducks” and “decorated shacks” was a call to judge buildings based on their function in the city, not on how loudly they announce themselves. If a project must be memorable, it should achieve this not by shouting your name with steel and glass, but by clarifying circulation, accommodating public life, and improving ordinary routines.

Designers who prioritize method over form are showing another way. In Stewart Brand’s book “How Buildings Learn,” adaptable frameworks that embrace change and maintenance as virtues are advocated; over time, such buildings age by gaining character rather than freezing a signature. In residential and public buildings, Lacaton & Vassal have turned this ethic into a mantra: “Never demolish, always add, transform, reuse.” In doing so, they create light and space for residents while protecting budgets, carbon emissions, and communities. This is the opposite of the style trap: a repeatable way of thinking that outlasts fashion.

Design for communities, not for awards

Awards can be encouraging, but they are not a summary. Projects that are constantly cited as turning points are usually those whose benefits to society are undeniable. The winner of the 2019 EU Mies Award was a project to convert 530 homes in Bordeaux. This project did not pursue innovation; it protected tenants, added winter gardens, and increased comfort without erasing the neighborhood. The award came because lives improved, not the other way around.

The RIBA Neave Brown Award sends a similar message by recognizing the UK’s best new affordable housing. The message is clear: quality matters in everyday life, and architects can champion this to the public. Similarly, Auburn University’s Rural Studio demonstrates that, over thirty years, thoughtfully constructed, functional buildings in resource-constrained communities can teach the profession more about service than any gala ceremony.

On the global stage, Alejandro Aravena’s ELEMENTAL project has become a benchmark for participatory and phased strategies. These strategies range from the “half-house” project in Quinta Monroy, completed by residents over time, to the disaster prevention forest designed with citizens in post-tsunami Constitución and the reopened public spaces. These examples are not about beauty but about taking action, demonstrating that architecture’s greatest honor lies in the functionality it provides for the people who live with it.

Authoring and Recognition Ethics

Credit is not a courtesy, but an ethical obligation. AIA’s Code of Ethics and citation guidelines clearly state that failing to acknowledge collaborators is one of the most common professional misconduct violations. RIBA’s Code of Professional Conduct emphasizes the same principle. When offices publish their work, submit award applications, or provide information to the press, acknowledging contributors is not optional; it is a way to maintain trust in the profession itself.

History also demonstrates the harm caused by obscuring or erasing authorship. The long campaign to recognize Denise Scott Brown alongside Robert Venturi, which began decades after the 1991 Pritzker Prize with a student petition, became a case study showing how the “lone genius” myth distorts credit and discourages talent. Designing beyond ego means designing beyond solitary authorship: clearly defining team roles, highlighting partners and advisors, and ensuring that community co-authors are visible wherever the results are celebrated.

If you want your work to be greater than yourself, create processes that are greater than yourself: write place- and use-based narratives; measure comfort and performance with the people inside; resist the lure of a rigid signature; let communities define their own summaries; and see praise as part of the craft. Do this consistently, and the building’s reputation will belong to those who live in it long after your signature is gone.

Developing Emotional Integrity Through Design

Architecture as a Reflection of Inner Values

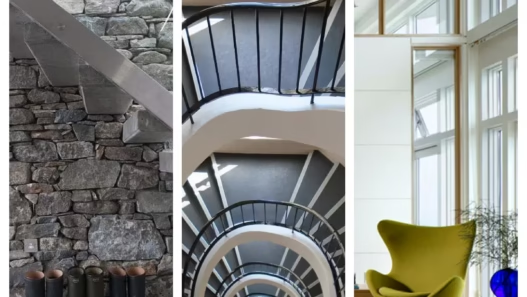

Emotional integrity begins with the quiet decision to let places speak before you do. When a designer pays attention to how light falls on a wall, how footsteps echo in a corridor, or how wood smells after rain, they are saying that human experience is more important than signature images. Juhani Pallasmaa argues that architecture is perceived with the whole body (eyes, ears, skin, and memory) and that when we design using all our senses, we reveal what we truly value: care, patience, and respect for lived moments.

This internal stance changes the way we read a site. Christian Norberg-Schulz’s idea of genius loci frames design as a conversation with the spirit of a place. If we treat topography, climate, and local rituals as co-authors, the resulting form feels inevitable rather than imposed. In this sense, emotional integrity is not an aesthetic; it is an attitude of listening—an attitude that allows a place’s character to guide decisions from threshold to roofline.

The Role of Empathy in the Design Process

Empathy is a method, not a state of mind. Communities help shape the narrative, and empathy becomes real when they retain control. Sherry Arnstein’s “Ladder of Citizen Participation” reminds us that there is a spectrum ranging from symbolic consultation to real power sharing; the closer we get to partnership and delegation of authority, the more we reflect the feelings and priorities of project users.

Collaborative design provides a toolkit for this ethical approach. Elizabeth Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers demonstrate how involving non-designers in research, sketching, and prototyping processes changes both the solutions themselves and the relationships surrounding them. The result is not just a user-friendly form, but also co-authorship—spaces that people accept as their own because they contributed to their creation. Following the opening day, post-use evaluation completes the cycle by converting comfort, clarity, and satisfaction into measurable feedback, guiding fine-tuning. Empathy thus becomes not a performance, but a continuous practice.

Healing Spaces and Performance Spaces

A space “fulfills its function” when it achieves its goals on paper; it “heals” when it truly improves bodies and minds. Roger Ulrich’s groundbreaking research showed that simply looking at trees reduced the use of pain medication and shortened hospital stays after surgery. This proved that the interest in nature is not emotional, but a clinical reality. Ulrich’s subsequent research linked daylight, acoustics, orientation, and family areas to safer and calmer care. Healing is a system composed of small acts of kindness coming together.

Noise is a silent enemy. The World Health Organization’s guidelines link environmental noise to stress and sleep disorders, noting that this directly impacts recovery and daily well-being. Designing for acoustic tranquility through planning, material, and mechanical choices is an act of empathy written into the ceiling and walls. Maggie’s Centres embody this ethic: a home environment, gardens, and soft thresholds that support people and families during their most difficult days. This model demonstrates how architecture can offer dignity and courage without acting as if it is healing.

Fragility and Integrity in Material Selection

Materials have character; they age, stain, and tell us their stories. Kenneth Frampton’s “tectonic” perspective treats structure as a moral language and argues that the way objects are joined can prevent architecture from becoming superficial. When you allow stone to look like stone and wood to wear, you allow time and touch to become part of the story. This fragility—accepting rather than hiding the patina—builds trust between people and place.

Integrity is also a chemical matter. Health Product Declarations and Declaration labels ensure that architects, building occupants, or installers avoid using substances harmful to them by transforming hidden ingredients into transparent data. Choosing low-toxic, well-documented products is a silent promise to those who will breathe and live in these rooms. Emotional integrity at the level of a door handle or sealant means rejecting the unknown that provides convenience.

When Design is Aligned with Personal Truths

When a building’s purpose and the architect’s values come together in harmony, you can feel that harmony. At the Paimio Sanatorium, Alvar and Aino Aalto tailored everything from colors to furniture to the comfort of tuberculosis patients, viewing the architecture as a medical tool and the forest as an auxiliary therapist. This project is remembered not for its grandeur, but for the sensitivity achieved through technical skill.

Peter Zumthor’s Therme Vals offers a different kind of wholeness: a choreography of stone, water, light, and silence that invites people to slow down and live in the moment. Its power is not a concept explained on the wall, but the lived experience of warmth, echo, and shadow. When your inner commitments—care, slowness, the naturalness of materials—align with the needs of a space and a community, architecture ceases to strive to be impressive and begins to gain meaning.

Learning from Successful Architects

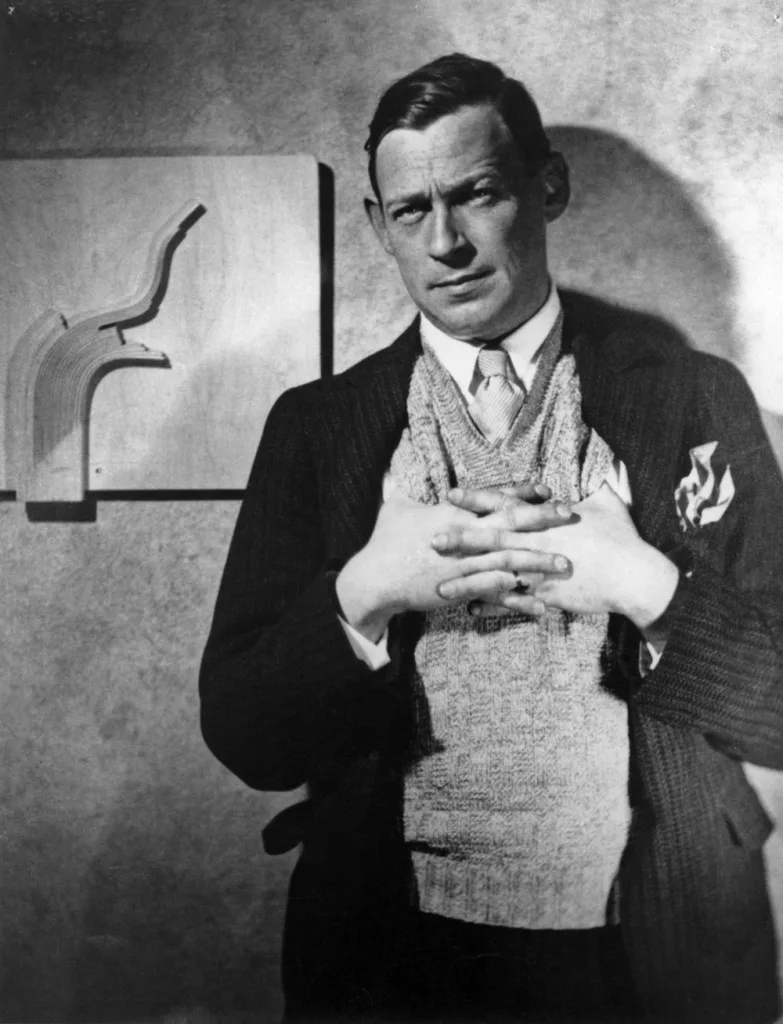

Lessons to be Learned from Alvar Aalto’s Humanism

Alvar and Aino Aalto viewed buildings not as objects to be admired, but as tools for living well. This approach is clearly evident in the Paimio Sanatorium, where direction, airflow, color, and furniture are harmoniously arranged to help tuberculosis patients rest and breathe more comfortably. Even the famous Paimio chair was designed to facilitate breathing and ease cleaning, transforming furniture from a purely decorative element into a clinical aid. This project introduced Aalto’s human-centered modernism to the world and remains a guide for designing for healthy living today.

Aalto’s “gentle modernism” combines technology with a sense of touch. He and his collaborators integrated architecture, interiors, and objects, preferring natural materials and sensory richness over hard-edged displays. MoMA once described this approach as “between humanism and materialism.” The lesson for contemporary practice is simple: design every layer, from sunlight to handrails, from chairs to window handles, as part of a single human narrative.

Glenn Murcutt and the Power of Modesty

Glenn Murcutt’s slogan, “touch the earth lightly,” is not just a slogan, but a method. Working mostly alone and almost entirely in Australia, Murcutt designs slender, climate-responsive buildings that stand elevated above the ground, balance heat with wind, and deflect rain with skillfully designed roofs. His modesty is deliberate: minimal footprint, maximum spatial harmony. In a noisy age, Murcutt’s houses argue that restraint can be radical.

His legacy stems not from ostentation, but from results. From Marie Short House to his subsequent works, passive performance, delicate details, and client comfort have always been paramount. This discipline, repeatedly affirmed by the Pritzker jury, offers a template: start with the climate, listen to the site, and let the building speak.

Carlo Scarpa’s Respect for Craftsmanship and History

Carlo Scarpa demonstrates how to renovate old spaces without erasing their memory. At the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona, he carefully added cuts and joints to the medieval castle, allowing visitors to feel both the weight of history and the clarity of contemporary approaches. Each hinge, staircase, and display arm serves as a small experiment in how the old and the new can communicate with each other.

Brion Cemetery and the Olivetti Showroom both demonstrate the same devotion to material and ritual. At Brion, concrete, water, cypress trees, and light create an intimate setting for mourning; in Venice, the small Olivetti store becomes a jewel with its glass, stone, and floating staircases that reveal a narrow room opening onto the city. Scarpa’s craft is not a fetish; it is the embodiment of ethical values such as time, construction, and respect for the visitor’s body.

Hassan Fathy and Building for the Forgotten

Hassan Fathy believed that modern Egyptian life could be built using the wisdom of villages. In the 1940s, he designed New Gourna near Luxor using mud bricks, vaults, courtyards, and community workshops, documenting this project in his book Architecture for the Poor. This experiment faced political and economic obstacles, but the goal of creating low-cost, low-energy, culturally resonant housing established Fathy as a cornerstone of sustainable, human-centered design.

Time has complicated and deepened the story. Some parts of New Gourna have deteriorated, but since 2019, UNESCO and its partners have been restoring important public buildings such as the mosque, theater, and crafts center, highlighting the project’s heritage value and drawing lessons for today’s climate and housing crises. Fathy reminds us that serving the poorest is not a side project, but the fundamental moral test of architecture.

Redefining Heritage: Contemporary Voices

Architects’ legacies grow not through their egos, but by expanding their spheres of influence. Francis Kéré’s schools and community halls, built with local materials and the labor of local workers, demonstrate that beauty, performance, and community ownership can coexist in harmony. The Pritzker jury recognized this synthesis in 2022, but this recognition came after years of collaborative work. Marina Tabassum’s Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka offers a similar lesson: built with donations from neighbors, this bright brick structure creates dignity through light and air rather than expensive ornamentation.

Another current topic is the ethics of transformation. Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal’s residential renovation projects (with added winter gardens, avoiding demolition) demonstrate how it is possible to provide people with more space, comfort, and pride without displacing them. They summarize this approach with the slogan “Never demolish. Always transform.” The common thread among these voices is clear: Measure impact by care, impact power, and longevity, and accept praise as a byproduct.

We Build Not Just Structures, But Systems

Designing Processes with a Longer Lifespan than the Project Duration

If you want your project to continue developing after delivery, design the process with the same care as the plan. Treat summary information as a living document, clearly state performance targets, and be close to the building during handover. Frameworks such as Soft Landings were invented precisely for this purpose: by involving designers in the commissioning and post-commissioning processes, they ensure that promises made on paper are tested in use and aligned with real feedback. In the UK, this approach has now been reflected in public guidance and tendering processes, with Government Soft Landings linking the entire process, from summary information to operation, to measurable outcomes.

Incorporate the cycle not only into your attitude but also into your workflow. The RIBA Work Plan has added a special “Usage” phase requiring post-use evaluation, user orientation, and light checks after relocation, along with a Usage Plan guide. This means collecting operational energy, comfort, and satisfaction data, sharing it with the team, and adjusting controls, signage, and management routines accordingly. Buildings become better when the project doesn’t end with a ribbon-cutting ceremony.

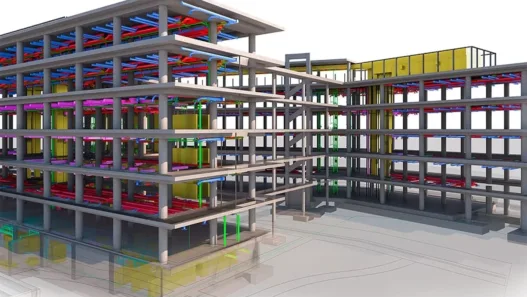

Make the information permanent. ISO 19650 provides a common language for naming, modifying, and managing asset data, so future owners and facility teams can actually use the information you deliver. Define asset information requirements early on (what needs to be tracked, in what format, and according to what acceptance criteria) so your digital twin doesn’t become a digital attic.

Mentoring and Knowledge Transfer

Studios that outlive their founders view mentorship as infrastructure. They codify how young people will learn, how responsibility will increase, and how craft and ethical rules will be passed on. In the US, the Architectural Experience Program defines the knowledge and behaviors expected for licensure and clarifies the roles of supervisors and mentors. These are clear and shared expectations that make learning accountable. In the UK, the RIBA student mentorship program places thousands of students in internship programs each year, transforming workplace knowledge into conscious teaching. The goal is the same in both systems: to make experience understandable, shareable, controllable, and improvable.

Good mentorship also builds culture. AIA’s Equal Opportunity Guidelines treat mentorship and sponsorship not just as education, but as tools for inclusivity. When companies treat credit, feedback, and growth as designed systems (regular one-on-one meetings, transparent career paths, libraries where detailed information and examples are shared), knowledge does not leak out when employees leave, and the values of the practice become teachable rather than random.

Architectural Literacy as Cultural Heritage

If heritage is what the people pass on to future generations, invest in the people’s literacy. Open House festivals held worldwide have transformed cities into classrooms, opening thousands of buildings and walkways to the public and enabling people to learn how spaces function and why they matter. In 2023 alone, 1.2 million visitors were recorded at 6,250 events organized with the support of thousands of volunteers. These are not just fun weekends, but also a driving force for consensus, a sense of responsibility, and future customers who can ask better questions.

Pair festivals with free archives. Archnet, an open-access library developed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and MIT, provides online access to tens of thousands of images, publications, and teaching resources, focusing particularly on architecture in Muslim communities. When citizens, students, and professionals can examine examples without paywalls, shared resources are strengthened and dialogue expands.

Open Source Architecture and Shared Value

Open source, in the truest sense of the word, means sharing not only the photo but also the recipe. WikiHouse publishes a modular, digitally manufactured wood system under open terms. This allows communities and small businesses to download the parts, process them locally, and quickly assemble high-performance structures. What matters is not a single object, but a repeatable method, a network, and a culture of collaboration in an open environment.

There are other “code bases” to which architects can contribute. OpenBIM standards such as IFC are vendor-independent building data schemas published by ISO; when you deliver IFC-compliant models, you ensure a handover that remains valid in the future, makes inspections and analyses portable, and allows clients to choose tools without losing their history. In the housing sector, ELEMENTAL’s incremental housing ideas have been examined, critiqued, and widely shared, leading to open guidelines and research on resident-led expansions. This proves that generous frameworks go beyond finished objects. Beyond buildings, the OpenStreetMap community continues to produce open geographic data that supports planning, disaster response, accessibility tools, and local advocacy. When the plan is made public, the shared value increases.

Not Just Portfolios, Building Platforms

A portfolio showcases what you have done; a platform enables what others can do. Think of an application as an operating system: briefing and measurement standards, open templates for community participation, detailed libraries and material policies that anyone can reuse, and research laboratories that publish not only images but also methods. Organizations like BuildingSMART were established to maintain these common rails so that the work of different authors can work together seamlessly for decades. When you align your internal playbooks with open standards, your projects cease to be isolated works and become elements contributing to a larger ecosystem.

Platforms can be not only digital but also social. MASS Design Group’s model, which shares efforts between buildings and research laboratories, demonstrates that an application can publish guidelines on justice, health, and memory while being built together with communities. Similarly, SEED Network transforms “good intentions” into accountable steps that others can adopt by offering a method and principles for public-benefit design. If you create spaces for knowledge circulation (festivals, guides, datasets, standards), you stop optimizing for the next award and start increasing public capacity. This is how a system becomes a legacy.

Protecting Your Mental Health in a Challenging Profession

Burnout and the Myth of Endless Productivity

Architecture often rewards those who are the last to leave, respond to every email, and view exhaustion as proof of dedication. However, burnout is not a badge of honor; it is a clinical condition. The World Health Organization classifies it in ICD-11 as a professional phenomenon with three defining characteristics: fatigue, cynicism, and decreased productivity. In other words, the more you push your limits, the more inadequate you become, and this harms both you and the project.

Health costs are real. According to a joint analysis by the WHO/ILO, regularly working 55 hours or more per week increases the risk of stroke by about one-third and the risk of dying from ischemic heart disease by about one-sixth. If the profession normalizes these working hours, it normalizes the harm. It would be wiser to value depth over time: focused work blocks, mindful breaks, and a culture that sees rest as part of the job.

This situation has also been confirmed in surveys conducted within the industry. Reports on architects’ workload and well-being repeatedly emphasize that excessive overtime is the primary cause of burnout and that protected leave through process improvements offers a practical way to alleviate this. Redefining productivity as “good work that you can sustain continuously” is not a luxury; it is a professional duty to your clients and yourself.

Drawing the Line Between Work and Values

One way to protect your time is to clearly set boundaries. Many countries have introduced a legal “right to disconnect” that restricts communication outside of working hours. A law enacted in France in 2017 requires large companies to establish rules for communicating outside of working hours. In Portugal, employers are prohibited from contacting employees during rest periods, except in emergencies. Even if such laws do not exist in your region, their existence serves as a useful precedent for company policies and customer expectations.

Ethics supports these boundaries. The AIA Code of Ethics reminds architects of their obligations to the public, clients, and the profession; these standards are difficult to uphold when exhausted. Institutions in the UK similarly emphasize well-being and conduct, while the RIBA has published mental health resources for practitioners and reiterated professional standards in its rules. Protecting your time outside of working hours is not selfish; it is a way to keep your judgment clear in order to protect your health, safety, and well-being.

Balancing Vision with Financial Reality

The vision requires a workable contract. AIA’s B101 contract separates basic, additional, and supplementary services, allowing teams to determine what is included, when additional fees apply, and how changes are approved. Combine this with a simple change management routine (identify, report, approve, and document the change) and prevent the scope from gradually expanding, making it a manageable choice. The RIBA Work Plan helps align tasks, fees, and outcomes step by step by providing a parallel process map from the brief to building use.

Market data can set expectations. Recent AIA and RIBA comparative analyses show that revenues have recovered after the pandemic, but margins have narrowed. This means that being generous without restrictions will quickly lead to self-destruction. Treat unexpected situations and post-use support as separate items in your budget. By setting realistic prices, you can preserve the energy needed to do your best work.

Bringing Joy and Play Back into the Design Process

Joy is not the opposite of diligence; it is a prerequisite for diligence. Psychological research shows that positive emotions and periods when the mind is free-flowing can increase creative problem solving. That’s why groundbreaking ideas emerge in the shower or during a quiet walk. Planning your week to include “incubation” time—such as practical model hours, working on materials, or device-free walks—can help ideas emerge naturally and on time.

Structured play also works at the team level. Methods such as LEGO® Serious Play® use simple building processes to bring out shared thinking, helping groups uncover their tacit knowledge and see options they couldn’t reach through talking alone. Bringing this spirit to critiques and workshops brings design back to its curious essence; here, trying, testing, and laughing are not a waste of time, but the fastest way to achieve clarity.

When to Say No: The Power of Creative Rejection

Saying no is an act of design. Ethical guidelines exist to help you refuse work that jeopardizes public health, safety, and well-being, or conflicts with your professional standards. If a brief asks you to disregard life safety, engage in greenwashing, or cut corners you cannot defend, the Code provides you with a solid basis to refuse and explain why.

Collective commitments can reinforce this stance. Networks such as Architects Declare encourage aligning work with climate and biodiversity goals, openly sharing information, and redirecting harmful projects. The principles of the Design Justice Network go even further, calling on designers to center affected communities and measure success by real benefits rather than intent. Refusal is not withdrawal; it is choosing to direct your limited efforts where they will do the most good.

In a field that can consume your time and energy, protecting your well-being is a practical necessity. Set clear boundaries, document them in your agreements, and support them with evidence and ethical guidelines. Plan weeks that allow time for rest and recreation to keep your focus sharp. And remember that some of your most important design decisions are the ones you reject, because your legacy is not just what you build, but who you become while building it.