Architectural Features of Traditional Sacred Places

The architecture of sacred spaces is characterized by symmetrical plans oriented toward God and an emphasis on height based on vertical lines. The use of natural materials such as local stone, brick, or adobe in the construction materials reinforces both regional identity and spiritual attachment. The stained glass windows and carved stonework found in the interior spaces create a mystical atmosphere through the interplay of light and shadow.

Period and Cultural Context

From the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, sacred spaces were constructed as symbols of both political and social identity. In Ottoman-era mosques, the central dome, arcaded courtyard, and minaret design integrate Islamic rituals with the space. Regional variations demonstrate how local cultures are reflected in architecture; for example, the differences between stonework in Anatolia and geometric decorations in Andalusia leave traces of cultural interaction.

Sacredness and Sense of Place

Defining the ritual area as a separate zone in sacred spaces reinforces spatial hierarchy. At the same time, the use of light intensifies the sense of sacredness; the direction and amount of natural light entering the interior determines the atmosphere of worship. The acoustics of the space also deepen the spiritual experience by allowing prayers to echo.

The Influence of Modern Architectural Movements

From the mid-20th century onwards, modernism embraced simplicity in sacred spaces by reducing ornamentation through functional approaches. Structures such as Tadao Ando’s Light Church (1989) reinterpreted ritual through the interplay of light and shadow on concrete surfaces. Minimalist designs aimed to focus on the essence of worship and highlight the spiritual elements of the structure.

Important Examples That Inspire

Göbekli Tepe, the oldest temple complex in human history, reminds modern designers of the power of symmetry and stonework. Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp Chapel (1955) transformed the perception of spiritual spaces with its organic forms. Today, the Al-Mujadilah Mosque in Qatar blends contemporary form and technology with sacredness in a special prayer space designed for women.

The Beginning of the Architectural Transformation Process

In the post-industrial era, restoration and adaptation projects began with efforts to preserve the spiritual fabric of old buildings. These approaches aim to meet modern usage needs while prioritizing the historical identity of the building. Thus, sacred spaces become living structures that both engage in dialogue with the past and respond to today’s worship practices.

Design Philosophy and Concept Development

Redefining Sacredness

Traditional sacred spaces have found meaning through fixed forms that represent specific religious rituals and social values. Modern designers, however, have begun to reinterpret sacredness as more than just ritual, viewing it as the function of the space to separate the sacred from the profane, establish dialogue with the community, and trigger inner transformation. In this approach, the sacredness of a space is not merely conveyed through structural symbols but through design strategies that transport visitors into an “threshold experience.”

The Spiritual Dimension of Space

The spiritual dimension of a space is shaped by qualities that go beyond physical elements and trigger the user’s inner experience. This experience is enhanced by finely tuned acoustic arrangements, sensory elements blended with minimalism, and spaces that invite meditation. Research indicates that the spiritual impact of a space is not solely tied to its visual components but also to its ability to manipulate perceptions of depth and height, thereby creating a subtle atmosphere of sacredness.

Balance of Form and Function

In modern sacred architecture design, the symbolic dimension of form is considered alongside functional flow. Functionally, corridors and ritual spaces that guide the flow of worship are connected by the clean lines of the form, offering visitors both freedom and a guided experience. In Jean Nouvel’s Sharaan Project in AlUla, functional modules embedded within natural forms reinterpret this balance in a contemporary language.

The Semantic Role of Material Selection

The choice of materials in sacred spaces reflects both regional identity and spiritual connotations. Natural materials such as local stone and adobe emphasize connection to the earth and continuity, while contemporary options like concrete, glass, and metal suggest timelessness and universality. In examples of Sacred Geometry Architecture, the combination of materials with geometric patterns adds both aesthetic and symbolic depth.

Approaches to Light, Shadow, and Atmosphere

Light and shadow play are among the most powerful tools in sacred space design. Structures such as Tadao Ando’s Light Church emphasize ritual moments and transform the atmosphere with natural light strips falling on concrete wall surfaces. In addition, the use of transparency and reflectivity redefines the boundaries between interior and exterior spaces, reshaping the visitor’s perception.

Sustainability and Spirituality

Green temple projects combine sustainability principles with the concept of sacred space. In this approach, rainwater harvesting systems, passive climate control, and renewable energy use integrate ecological awareness with spirituality. Julia Watson’s Lo-TEK studies represent the ecological wisdom of indigenous communities and propose forms of sustainable sacredness.

Structural and Technical Innovations

Conveyor System Solutions

The arch and vault systems used in traditional large-span sacred spaces are being reinterpreted today using high-strength steel and concrete composites. For example, Shigeru Ban’s Katana Cathedral combines recycled steel supports with wooden beams to create a lightweight yet durable structural system. These hybrid systems enhance flexibility against seismic, wind, and snow loads while ensuring that the worship space can be experienced with uninterrupted openness.

In addition, thanks to the precise engineering tolerances of prefabricated concrete elements, construction assembly on site is accelerated while quality control is brought up to factory standards. This approach offers time and cost advantages, particularly in large-scale mosque and cathedral projects, while also enabling aesthetic integrity to be maintained.

Use of New Materials and Technology

Contemporary sacred structures are now being constructed using advanced materials such as glass fiber reinforced concrete (GFRC) panels, mass modified polymers, and carbon fiber rods. GFRC allows for the production of complex geometric patterns and delicate structural elements, while carbon fiber reinforced concrete offers significantly high tensile strength.

In addition, photovoltaic glass facades offer innovative solutions that combine natural light transmission and energy production. The use of integrated PV glass in a place of worship in San Jose met 30% of the total electricity consumption in one year. This technology reinforces the symbolic “light” theme of the sacred space in both a metaphorical and practical sense.

Acoustic and Spatial Comfort

Acoustics in sacred spaces should be designed to ensure that prayers, hymns, and sermons can be heard clearly. Modern acoustic panels optimize both sound absorption and diffusion, controlling reverberation to the desired degree. Parametric panels, particularly those installed on ceiling forms and side wall surfaces, distribute sound waves evenly throughout the space.

Digital acoustic simulation tools provide designers with clear data by calculating expected reverberation times and frequency distributions in advance of construction. This allows worship services to balance mystical silence with the necessary acoustic liveliness.

Energy Efficiency Strategies

Modern sacred buildings minimize energy consumption through passive climate control, geothermal systems, and smart automation integration. The Sultan Qaboos Mosque in Oman uses the natural chimney effect of its roof dome to provide passive ventilation for the interior and reduce the cooling load by 25%.

LED lighting and motion sensor-controlled zone control systems automatically adjust lighting according to prayer times, preventing excess energy consumption. In addition, rainwater harvesting and greywater recycling systems save water across a wide range of applications, from landscape irrigation to toilet cisterns.

Modular Approaches in the Construction Process

Modular prefabricated units promise speed and flexibility in the construction of sacred spaces. BOXX Modular’s mosque and church modules are completed in a factory environment and assembled on-site, reducing construction time by 40% compared to traditional methods.

This method offers scalability and reconfiguration possibilities, especially in community-centered worship buildings. A church can easily divide its modular hall according to the community events taking place.

Digital Design and BIM Integration

BIM (Building Information Modeling) enhances interdisciplinary coordination in sacred space projects. The Revit-Dynamo-based automation developed by Tran and colleagues enables the parametric modeling of traditional Islamic motifs and reduces design time by 30%.

BIM also provides critical data during the maintenance and operation phases. Building managers and facility managers can monitor information such as material replacement, energy consumption, and acoustic performance throughout the life of the building using the BIM model. As a result, sacred structures remain sustainable in the long term, both aesthetically and functionally.

Spatial Organization and User Experience

Visitor Entrance and Reception Areas

The first impression of sacred spaces is determined by the architectural language of the entrance hall and reception area; this space becomes a threshold that invites visitors to a “special” experience. A spacious, well-lit entrance hall facilitates the visitor’s transition into the space’s silence and sanctity, while material choices—stone, wood, or glass—offer both an aesthetic and tactile welcome. These areas also feature clear circulation flows supported by wayfinding signs and natural light, enabling the smooth movement of the community.

Main Places of Worship or Activities

The main place of worship usually attracts attention with its wide opening and focal point; the seating arrangement around the mihrab, altar, or sacred monument allows the community to experience togetherness. Here, the high ceilings, large openings, and symmetrical layout reinforce the sense of sanctity. At the same time, movable seating elements and divisible panel systems enhance the space’s flexibility for different types of activities.

Transition and Circulation Strategies

Circulation axes are designed to reflect the ritual sequence of the space and the psychological journey of the user; long corridors serve as a preliminary provocation, preparing visitors for the focal point. Branched or circular circulation paths facilitate social interaction after collective worship, while transitions between narrow passages and open spaces enhance the “transition experience.” Changes in floor coverings and lighting emphasize these turning points, providing intuitive guidance.

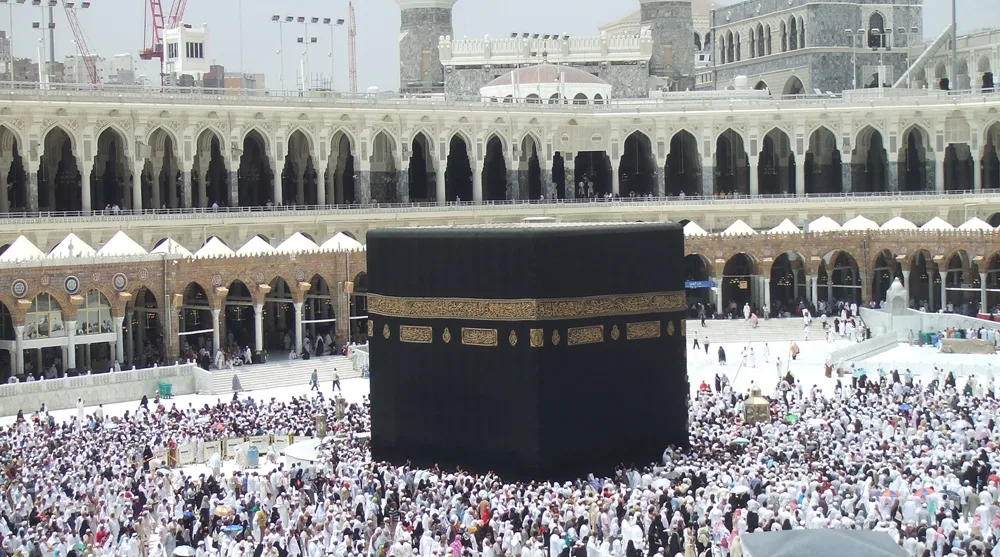

The Hajj in Mecca is an example of contemplative architecture that is of vital importance for meditation and prayer.

Recreation and Reflection Areas

The small cells or courtyards surrounding the main worship area offer visitors private corners for silence and introspection. These spaces allow visitors to step away from the main ritual of the space and engage in communal or individual reflection, supported by comfortable seating arrangements, skylights that let in natural light, and acoustic panels. Open-air courtyards connected to the landscape, meditation gardens, or water features further enhance relaxation and symbolic purification.

Sound and Light Journey Design

Sound and light are the most powerful tools guiding the ritual journey in sacred spaces; the changing brightness and color temperature at different points in the space shape the visitor’s emotional flow. Motion-sensor-controlled lighting highlights important moments of the ceremony, while echo duration and frequency distribution simulations create a mystical atmosphere for the sounds of worship. These interactive systems establish a dynamic dialogue between the physical space and the ritual.

Accessibility and Universal Design

Accessibility in sacred spaces is not limited to ramps and elevators; Braille directional panels, audio guidance systems, and color contrasts within spaces provide an experience that appeals to all senses. Universal design principles ensure that spaces can be used equally by individuals with different abilities, thereby strengthening the social inclusivity of sacred structures. Recently developed “affirmative disability design” approaches blend aesthetics and functionality to make accessibility a celebrated feature.

Cultural and Social Impacts

Local and Global Context

Sacred spaces take shape through the building materials and formal language of local identities, while also transforming into a universal language under the influence of global architectural trends. The use of regional materials keeps the cultural memory of the community alive; for example, Geoffrey Bawa’s projects in Sri Lanka’s Tropical Modernism examples refer to both the local climate and global modernism. On the other hand, international places of worship enable architecture firms from different regions to come together and establish common design parameters; the Lusail Interchange Mosque in Qatar is a structural hybrid that brings together Arab and Western design schools.

Social Participation and Ownership

Modern sacred space projects involve participatory processes that include not only architects but also community members in the design process. As seen in examples of West African mosques, local artisans and the community play an active role in both the construction and subsequent maintenance phases of mosque construction. This participation ensures that the space serves not only as a place of worship but also as a social gathering point; in the restoration of the San Giovanni Church in Italy, restoration work carried out in collaboration with local volunteers has strengthened the sense of ownership of the space.

Cultural Continuity and Innovation

In the design of sacred spaces, continuity must be balanced with innovations that meet new needs. In the restoration of the Chapel at the Palace of Versailles, the classic Baroque aesthetic was preserved while modern fire safety systems and climate control infrastructure were integrated. This approach respects history while offering the comfort and safety provided by today’s technology. Following the same logic, during the reopening of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul for worship, the original Byzantine mosaics were preserved without alteration, while the structure was reinforced through meticulous engineering interventions.

Interactions between Art and Architecture

Art intertwines with sacred spaces, enriching both the structure and the rituals within. Last month, the venue of the Islamic Art Biennial held at Jeddah Airport reimagined the old pilgrimage terminal through contemporary art—from Arcangelo Sassolino’s massive steel sculpture to Asif Khan’s illuminated glass interpretation of the Quran—keeping architecture and art in dialogue. Similarly, at the Sagrada Família in Barcelona, Gaudí’s mosaics and stained glass windows interact with the building’s steel skeleton, designed to both refract light and impart a colorful rhythm to the space.

Tourism and Economic Contributions

Sacred structures are important tourist attractions beyond their role as religious centers. Their contribution to the local economy is measured by the number of visitors and their spending; the market set up every Monday around the Djenne Mosque contributes $1.2 million to Mali’s economy each month, while also supporting regional handicrafts. The Vatican Museums, on the other hand, welcome 6 million visitors annually, accounting for 20% of Rome’s tourism revenue.

Social Dialogue and Pluralism

Contemporary sacred spaces create areas of dialogue that bring together people of different faiths and cultures. The flexible design of the 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York, which hosts ceremonies and memorial rituals of different religions, aims to overcome historical trauma through social empathy. Additionally, interfaith centers demonstrate how peace and understanding can be established through architecture by placing Jewish, Christian, and Muslim worship spaces side by side under the same roof. These spaces reinforce a culture of tolerance within local communities while also serving as global models.

Future Perspectives and Conclusions

The Evolution of Spiritual Approaches in Architecture

Over the past sixty years, sacred spaces have evolved into a form of “spiritual architecture” that focuses on light and shadow play and simple forms, stripped of symbolic richness. In this approach, the sacredness of space is no longer defined by religious iconography but by the spatial experience itself; visitors are invited on an inner journey by crossing the psychological threshold created by high ceilings and controlled light refractions. In the future, these experiential strategies will be further deepened through advancements in parametric design tools and material technologies, with the “spiritual fabric” of space being pre-tested through digital simulations.

Sustainable Sacred Space Visions

The sacred structures of the future will be built on designs that are in harmony with ecological cycles. Places of worship constructed from recycled materials will generate their own energy through rainwater harvesting, passive climate control, and photovoltaic facades. For example, some modern religious structures utilize laser scanning and digital prefabrication during the design process to minimize material waste, reducing the carbon footprint by up to 95%. Additionally, the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings is emerging as a tool that preserves historical character while supporting ecological sustainability.

The Role of New Technologies

Virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) are redefining both the designer and visitor experience in sacred space design. Designers use VR simulations to test spatial rituals during the project phase, while AR applications that enable remote participation provide global access to worship rituals. Additionally, parametric modeling and AI-driven optimization analyze acoustic performance and light transmission in real time to create ideal experience scenarios.

Our Place in the Global Architectural Dialogue

Sacred space design is now transcending local aesthetic codes and becoming the subject of joint projects between international offices and interdisciplinary teams. This process is supported by UNESCO’s world heritage programs and international architecture congresses; for example, the “political, educational, and professional” perspectives discussed at the UIA23 Conference determine how sacred space design aligns with global sustainability and social inclusivity goals. Countries with a rich historical heritage, such as Turkey, contribute to this dialogue with unique material compositions and traditional construction techniques.

A Lasting Legacy for Future Generations

Spatial memory is passed down from generation to generation through sacred structures, which serve as the cornerstone of cultural identity. Conservation and restoration strategies must be designed to preserve both the physical and digital “fabric” for future generations; for example, digital twins created using 3D scanning data provide future architects and historians with a resource documenting the evolution of a structure. Additionally, socio-cultural projects that encourage community participation enable heritage to grow and transform like a living organism.

Looking ahead, it is clear that sacred space design will undergo a multi-layered transformation centered on spiritual experience, sustainability, technology, and cultural heritage. Experiential minimalism, environmental responsibility, and digital simulations will transform sacred structures into “living” spaces in both physical and virtual environments. In this process, local knowledge and global collaborations will create a powerful dialogue that redefines both the sacredness and social function of architecture.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.