From Toys to Vehicles: A Brief History

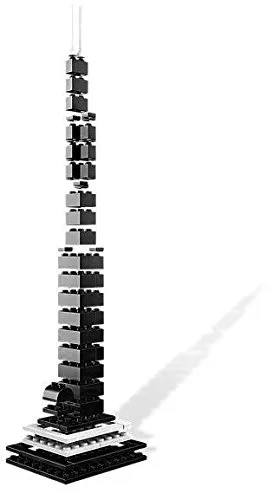

LEGO Architecture began in 2008 with compact, display-focused models of Chicago’s iconic buildings, the Willis Tower (then known as the Sears Tower) and the John Hancock Center. This series, which began in Chicago, evolved into a global series for adults, combining micro-scale modeling with booklets that explain the history and ideas behind each real building. This combination transformed a childhood toy into a simple tool for architectural literacy.

Over time, the set family expanded into focused series celebrating iconic buildings and city skylines around the world. Products like Villa Savoye and Farnsworth House demonstrate how minimal LEGO forms can convey proportion, structure, and space, while city skyline sets condense urban narratives into a shelf-sized panorama. Accompanying guides encourage students to compare the model with photographs and plans, reinforcing concepts such as mass, rhythm, and material expression.

Many kits contain short articles about the original architects and the design problems they solved. For example, the Fallingwater and Farnsworth House booklets explain cantilevers, the flow between interior and exterior spaces, and structural clarity in an accessible language, helping builders connect the tactile act of assembly with real architectural ideas.

Adam Reed Tucker’s Vision

Chicago-based architect Adam Reed Tucker pioneered this movement in the mid-2000s during a downturn in the real estate sector by rebuilding iconic structures using standard bricks. His experiments in his studio led to a partnership with LEGO and a pilot project that transformed complex towers into 20 cm educational models. The first official sets were released in 2008, laying the foundation for the build-to-learn approach that also appealed to adult fans.

Tucker’s goal was not just to sell the pieces, but to tell the story of architecture through bricks. He exhibited large-scale models in museums and created exhibition pieces such as the massive Taliesin West, built from 180,000 bricks. In this way, he demonstrated how a familiar material could convey structure, sequence, and space to a wide audience.

After defining the theme, he continued to explore architecture as a brick-based environment beyond the formal line, published his views in The Visual Guide, and later developed new models through independent ventures. His career demonstrates how professional applications, exhibitions, and consumer kits can influence each other to make design culture more accessible.

LEGO and the Democratization of Design

LEGO reduced design barriers by combining its building kits with community platforms. The company’s crowdsourcing approach began in 2008 as LEGO CUUSOO and was relaunched globally in 2014 as LEGO Ideas. On Ideas, anyone can propose a concept; projects that reach 10,000 supporters are reviewed for production. This model invites fans into the process and provides a pathway for niche architectural or design interests to reach store shelves.

LEGO has also encouraged design-focused thinking beyond its sets. Methods such as LEGO Serious Play transform bricks into a facilitation tool for teams to model systems, explore scenarios, and communicate their ideas. Researchers have documented how building with bricks and storytelling activate many forms of thinking. That’s why this approach is used in classrooms, studios, and workshops.

In architecture education, instructors use bricks for rapid massing studies, stability experiments, and participatory urban design games. These low-cost prototypes help students grasp concepts of scale, structure, and iteration before moving on to advanced software. When combined with official Architecture handbooks that explain real-world examples, the system broadens access to fundamental design concepts for students of all ages.

Iconic Buildings Redesigned with Brick

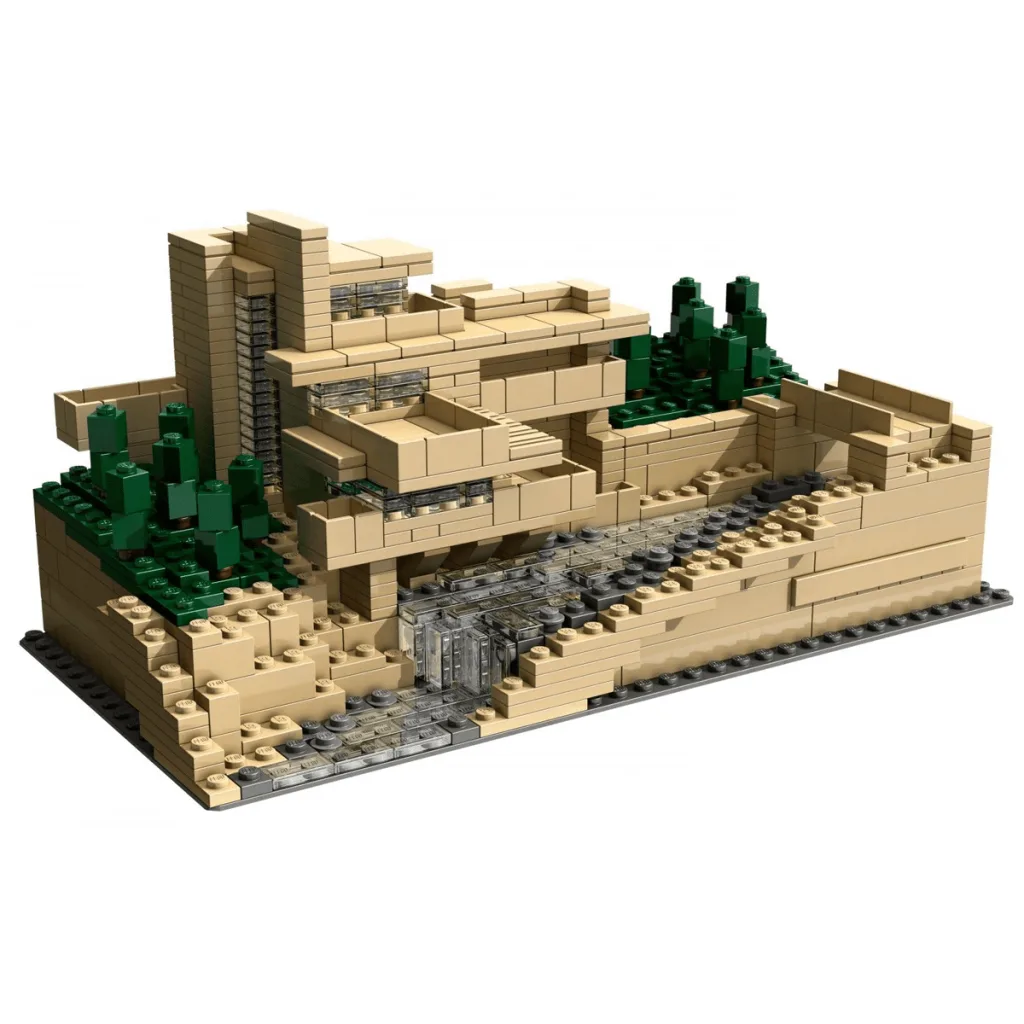

Fallingwater and the Essence of Wright

Fallingwater is renowned for being not beside nature, but within it. Frank Lloyd Wright placed a series of concrete terraces against a central stone chimney made of local Pottsville sandstone, so that the house appears to emerge from the rock above the waterfall. Strong horizontal lines, low ceilings, and the constant sound of water transform geology into a livable architecture.

The LEGO version (set 21005) brings these ideas to life with beige-colored plates for “trays,” textured bricks for stones, and transparent elements for the stream. The model features a detachable element that allows sections to slide out, revealing the layers and structure. This reflects an educational approach mirroring how architects examine plans and sections. The official instructions list 815 pieces, and the designer’s notes explain the sliding sections concept.

In studios and classrooms, this small structure quickly becomes a laboratory for consoles and load paths. Try extending the terraces with a few nails, add hidden “counterweights,” or compare the visual balance of narrow and deep projections. You’ll feel why the real house needs to be carefully reinforced and how mass, texture, and water can be read even at the micro level.

Eiffel Tower: Modular Splendor

LEGO’s 10307 Eiffel Tower is a model approximately 1.5 meters tall, consisting of 10,001 pieces. It consists of four stacked pieces that reflect the original tower’s construction sequence: the base and esplanade, the first platform, the second platform, and the flag-topped spire. Building this model teaches structural hierarchy: arches and legs at the bottom, denser cross-braces as the tower narrows, and small observation platforms at the top.

On the other hand, the Architecture set 21019 reduces the tower to 321 pieces, bringing it to a height that fits on a desk. The book summarizes important information about Eiffel’s wrought-iron lattice and the 1889 World’s Fair, so the model also serves as a compact history lesson. Comparing the two scales is an educational experience: the large set emphasizes geometry and assembly sequence, while the small set highlights the silhouette, proportions, and recognition of iconic structures.

The urban context is also important. The 10307 base includes trees, benches, and street lamps that frame the tower in its urban setting. Such small details spark conversations about how monuments blend into the ground, how people move around them, and how public space completes a building’s story.

UN Headquarters: Symbolism in Plastic

The United Nations complex is a campus located on the East River and consists of four main sections: the low-rise General Assembly building, the long Conference Building, the 39-story Secretariat tower, and the library. This complex was designed by an international team led by Wallace K. Harrison and completed through a collaborative process appropriate to the organization’s global mission, with contributions from Oscar Niemeyer and Le Corbusier.

LEGO’s 21018 set reflects this community with 597 pieces. You can see the glass-fronted Secretariat building, low-rise assembly volumes, and the row of columns stretching along First Avenue. The booklet included with the set summarizes the project’s history and design background, transforming the quick build into a study of modernist forms and diplomatic space planning.

As a model, it is perfect for discussing campus planning and symbolism. The contrast between the tower with its transparent curtain walls and the solid meeting rooms can spark conversations about visibility, ceremonies, and working infrastructure; about how a symbolic building overlooking the city has become a daily workspace for global collaboration.

Architectural Principles with LEGO

Understanding Scale and Proportion

LEGO provides a clean, repeatable grid that functions like a studio’s scale bar. The width of a stud is approximately 8 mm, the height of a brick is 9.6 mm, and three plates equal the height of a brick. Once you internalize this math, you can translate facade rhythms, window projections, or stair treads into consistent modular increments that remain consistent from model to model.

With this grid in mind, the “half-stud” and “plate height” movements become precise tools. Jump plates create half-stud offsets to center doors or align pilasters, and turning elements sideways (SNOT) allows you to match horizontal and vertical dimensions that wouldn’t align with a simple stack. The result is better ratio control at micro scales where a single stud would feel too coarse.

Structural Integrity with Locked Units

LEGO’s stud and tube geometry is a miniature structural system. Introduced in 1958, the tubes on the underside lock onto the studs to create “grip strength.” This allows even small interlocking patterns to resist being pulled apart, keeping the model stable when you pick it up. This friction-based compatibility is the fundamental element that allows you to explore snap-together, belt, and console structures without the need for adhesive.

ABS plastic is more durable than most people expect. Open University tests have reported that a single brick can withstand the weight of approximately 375,000 bricks without breaking. This implies that, theoretically, a tower several kilometers high could be built if stability were not a limiting factor. In practice, this explains why short, well-bonded stacks feel rock-solid to builders and why wide bases are important for tall models.

Good integrity also means respecting tolerances. LEGO designers avoid “illegal” connections that apply pressure to pieces, such as squeezing pieces that don’t fit geometrically, because accumulated pressure weakens the structure over time.

Material Restrictions That Encourage Innovation

Constraints encourage creativity. A limited brick palette and fixed geometry guide you toward abstract forms, allowing you to find clean silhouettes and select one or two details that reflect the building’s identity. Techniques such as SNOT (studs not on top) expand this palette by turning connection points sideways, allowing you to cover curves, align tiles as cladding, or add glass strips in the thickness of the plate.

The same constraint-focused approach is also seen in educational and application workshops. LEGO Serious Play uses bricks in these workshops to create prototypes of ideas, test metaphors, and uncover assumptions. Research in higher education shows gains in the areas of participation, reflection, and collaborative problem solving. This reflects what happens at the table when a difficult challenge is solved, due to the brick geometry requiring a clearer decision.

The Educational Power of LEGO Architecture

Building a Bridge Between Play and Pedagogy

LEGO connects learning through play by encouraging students to think with their hands. This idea is part of constructivism, a learning theory that states people understand ideas best when they build meaningful things. The LEGO Foundation’s evidence review on learning through play and Papert’s articles support this bridge between making and understanding.

In practice, bricks become a common language for reflection and discussion. Research on LEGO Serious Play shows an increase in participation, identity formation, and resilience in higher education classrooms, while programs such as BuildToExpress are designed to help students model abstract ideas and articulate their thoughts aloud. The result is a classroom where building, speaking, and thinking reinforce each other.

MIT’s work on programmable bricks adds a technological layer to this pedagogy. Mindstorms and the “programmable brick” transformed these models into systems that you can test, debug, and iterate on. This enables a deeper understanding of cause-and-effect relationships and opens the door to computational thinking for young students.

Introducing Design Thinking to Young People

Design thinking offers students a simple cycle they can remember and use: empathizing, defining, ideating, prototyping, testing. K-12 teachers use this sequence to develop empathy and problem-solving skills through low-fidelity models that evolve through quick discussions, brainstorming, and feedback.

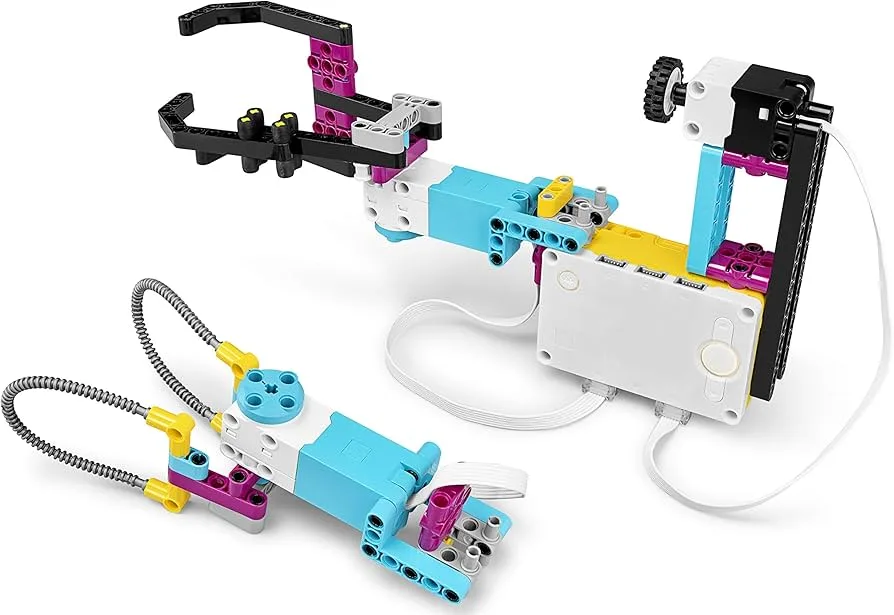

LEGO Education lesson plans bring this cycle to life. SPIKE Prime units such as “Design for You” and “Design for Someone” step-by-step guide lessons through defining user needs, sketching ideas, creating prototypes, coding, and evaluating what works. Challenge sheets require students to document their tests, identify constraints, and iterate, so that the process becomes a habit rather than a one-time activity.

Since these resources are standards-aligned and lesson-ready, teachers can incorporate them into their existing programs. The kits and lessons range from simple mechanisms to coded behaviors, so the same framework supports both beginners and more advanced groups in middle school.

LEGO in the Architecture Education Curriculum

Architecture and construction programs use LEGO in focused ways to connect drawings, models, and spatial reasoning. In a case study introducing BIM, students built a small house out of bricks after reading plans, elevations, and sections to experience the transition from 2D to 3D and discuss errors, tolerances, and sequencing. The tactile step made digital workflows less abstract for new learners.

Studios are also combining physical models with new media. In a recent study, brick models were combined with augmented reality using the LEGO House example, helping students test design variations and understand how small mass movements change perception. This hybrid approach adds layers of analysis and feedback while maintaining the clarity of the LEGO grid.

Highly disciplined projects complete the picture. Smart city platforms built with LEGO invite architecture and interior design students to design buildings integrated with engineering systems, allowing form, circulation, and infrastructure to be explored concretely on a campus scale. These collaborative structures mimic real project teams and encourage iteration throughout the semesters.

Creativity, Customization, and Community

The Rise of AFOL (Adult Fans of LEGO)

Adult LEGO fans, or AFOLs, have been organizing clubs, events, and media channels for decades. The LEGO Group officially communicates with this community through the LEGO Ambassador Network, recognizing online communities, fan media outlets, and local LEGO User Groups, enabling them to collaborate with the company and each other. This recognition framework helps fans access resources, coordinate events, and share best practices across regions.

AFOL culture comes to life at conventions and gatherings where builders showcase their original creations, trade parts, and teach techniques. Significant gatherings range from the Skærbæk Fan Weekend near Billund to city-wide events like Brickworld Chicago, and are often covered by fan media and dedicated YouTube channels. These events celebrate creativity and also serve as informal classes where newcomers learn how to plan, build, and present their work.

Open Source Design Culture

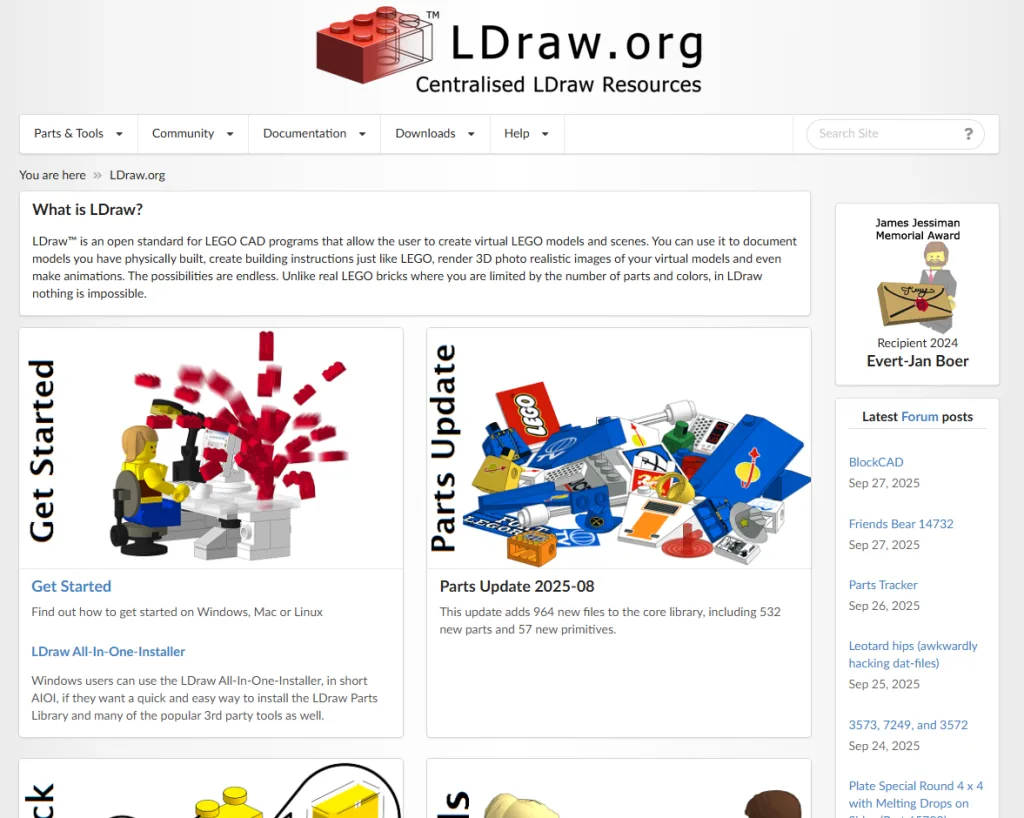

The most important driving force behind customization is the open and community-created toolchain. LDraw is an open standard and parts library that enables users to create virtual models, prepare instructions, and generate images. This community-managed, unofficial platform offers fans the freedom to experiment while providing a common file format and vocabulary for parts.

In addition to this standard, BrickLink Studio offers a widely used free desktop application that links designs to actual inventory and costs via the BrickLink catalog. Builders can check available colors, create instructions, and transfer part lists directly to the wish list for ordering. This streamlines the process from concept to purchase with minimal friction.

Sharing completes the ecosystem. Rebrickable hosts thousands of fan-made models along with instructions and analyzes your existing parts to suggest what you can build or which parts you need. The platform’s parts lists and collection tools encourage remixing and kit bashing, which facilitates the circulation of ideas within the community.

Introducing Social Media and Brick Talent

Fan media outlets help creators reach global audiences by documenting their work, publishing set reviews, and highlighting techniques. The Brothers Brick is a long-standing example that compiles featured MOCs and shares community news. Channels like Beyond the Brick publish in-depth convention tours and creator interviews that showcase processes and craftsmanship. These platforms serve as a vibrant archive of ideas and styles.

https://www.brothers-brick.com

The LEGO Group recognizes fan media within its Ambassador Network, which formalizes its relationships with independent sites and creators. Historically, the company has experimented with dedicated sharing hubs like ReBrick to make it easier for fans to showcase their work and discover others. Today, recognition programs and widely used social platforms help new creators find role models and learn to clearly present their work with photos, instructions, and part data.

Critical Reflections on LEGO as an Architectural Environment

The Limits of Representation and Originality

LEGO Architecture aims to capture the essence of buildings, not every detail. Designers work on a micro scale and rely on existing pieces, which leads to simplification and stylization rather than exact replication. The Notre-Dame review published on New Elementary clearly states this: the theme attempts to convey fundamental characteristics with limited geometry, and certain archetypes like Gothic vaults and arches are particularly difficult to express at this scale.

City skyline sets create another problem. Symbolic structures are rearranged and compressed to look good on the shelf, which can distort geographical reality. The San Francisco skyline is a good example of this. For composition and clarity, the Golden Gate Bridge is positioned unnaturally close to the Salesforce Tower. The model looks attractive, but the layout is not a realistic map.

Loyalty debates also arise at the object level. The 21042 Liberty Statue sparked lengthy discussions about the “face” solution at this scale, and commentators noted that the flat shield element represented a compromise that divided opinions. These criticisms reveal a fundamental tension: abstraction keeps the structure teachable and robust, but some symbols lose the characteristics that define their character.

Minimalism and Over-Simplification

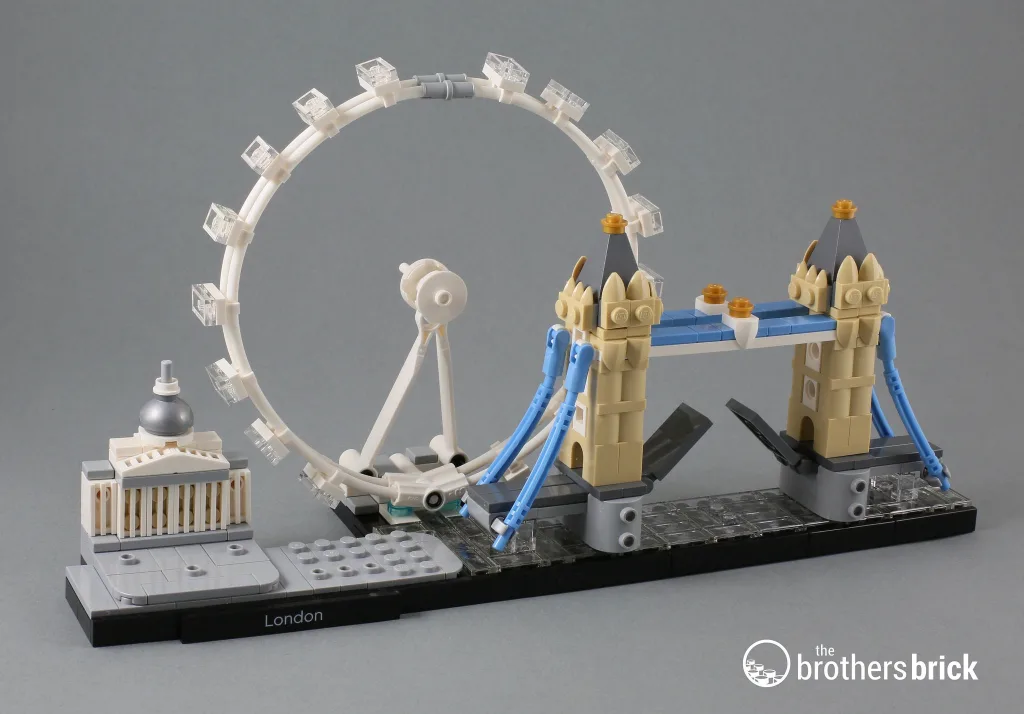

Minimalism can make what is important clearer. On a small scale, clean silhouettes and proportions often express a building better than small surface details. For example, the London Eye in the London skyline does not include the wheels because they are too thin at LEGO scale, yet the wheel is still recognized as the Eye. This is an example of minimalism working as intended.

Over-simplification is the exact opposite. Models risk becoming pictograms of buildings rather than spatial ideas by relying too heavily on printed tiles or flat patterns instead of complex envelopes. Brick Architect’s Tokyo review argues that over-reliance on printing can be perceived as a shortcut and diminishes the creative reuse value of parts for future structures. The broader lesson for designers is to reserve prints for critical moments and allow three-dimensional form to do the heavy lifting.

Even fans notice the line between elegant abstraction and the loss of magic. Writers who love the horizon line praise its legibility from a distance, but admit that some models flatten out when viewed up close. This reaction serves as a useful checkpoint in design: If a model looks great from afar but falls apart when you hold it in your hand, it has crossed the line from minimalism into excessive simplification.

The Debate on Consumerism and Collecting

In recent years, LEGO has clearly shifted its focus towards adults, first with packaging aimed at those over 18, and then with the LEGO Icons rebranding, which brought together sets designed for adults under one umbrella. This move has led to the emergence of larger, display-quality models and has also increased collectors’ interest in premium products.

Price is also part of this discussion. In 2022, the company announced that it would increase the recommended retail price of many sets, and enthusiasts have been tracking which themes and products have been most affected ever since. High prices conflict with the annual practice of removing sets from the market, which triggers fear of missing out and fuels a vibrant second-hand market when products appear on LEGO’s own “Last Chance to Buy” page or on media lists of discontinued products.

The economics of collecting can be quite intense. Academic studies and mainstream news reports have shown that some retired sets have gained value at rates that rival traditional assets. This encourages buying and storing, shifting the focus from collecting to banking. While this may be interesting from an economic perspective, it can overshadow the educational aspect of the hobby.

Sustainability adds a new perspective. When LEGO’s life cycle analysis showed that emissions could increase, it halted a high-profile experiment to switch to recycled PET and instead doubled down on a science-based target to reduce absolute emissions by 37% by 2032 while exploring other material pathways. For architects and educators using bricks as tools, choosing paths with a lower carbon footprint is important when selecting between new sets, second-hand parts, or digital modeling.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.