The Lost Spaces of Social Cleanliness

Once indispensable centers of hygiene, community, and rituals, bathhouses are disappearing worldwide or undergoing a major transformation. In Japan, modest neighborhood bathhouses called sento are rapidly declining: while there were approximately 18,000 bathhouses nationwide at their peak in 1968, only one-tenth of those (about 1,800) remain today. In Tokyo alone, the number has fallen from 2,600 in the 1960s to less than 500 today. This decline, coupled with the spread of private bathrooms in homes and younger generations losing this habit, has led many sento owners to retire without successors. Europe’s historic baths also face their own challenges. Some Ottoman-era baths in cities like Istanbul have closed or survive mainly as tourist attractions. Even magnificent thermal complexes like the Gellért Baths in Budapest will be closed for several years to address structural issues. However, not all bath cultures are disappearing. In Finland, the sauna culture is so strong that it was included in UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2020. In Hungary, Budapest’s thermal baths remain an important part of city life, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors each year (the Gellért Baths welcomed 420,000 visitors in 2024 before its planned renovation). These examples suggest that “collective hygiene” may continue in new forms.

Why are we fighting to preserve or revitalize public baths? This is not nostalgia for washing shoulder to shoulder. Historically, baths offered more than just cleanliness: they were daily health centers, providers of social equality, and places of spiritual renewal. In an age of widespread individualized living and loneliness, if architects and policymakers can redesign these communal spaces to meet modern needs, they can serve as social infrastructure. The challenge here is to strike a balance between safety, dignity, and cultural richness: How can bathhouses be designed to meet strict health standards and diverse user expectations without compromising the atmosphere that makes them unique?

From Washing to Social Ritual: What Makes Bathing Social?

A well-designed bathhouse transforms the act of washing into a shared social ritual.

This is not just about getting wet; it is about the spatial journey and atmosphere that allows foreigners to slow down, adapt, and feel part of a community. Architecture plays a central role in this transformation. From the sequence of thresholds to the orientation of spaces, the choreography of light, sound, and heat, key elements create a ritual structure that distinguishes a hamam from an ordinary pool or shower facility. By examining traditional models such as Japanese sento and Turkish baths alongside modern interpretations, we can determine how design transforms personal hygiene into a public cultural experience.

Inside a restored 16th-century bathhouse in Istanbul, featuring its iconic domed ceiling adorned with star-shaped observation holes and the central heated marble platform (belly stone). Such spatial elements lend a contemplative focal point and rhythm to communal bathing rituals.

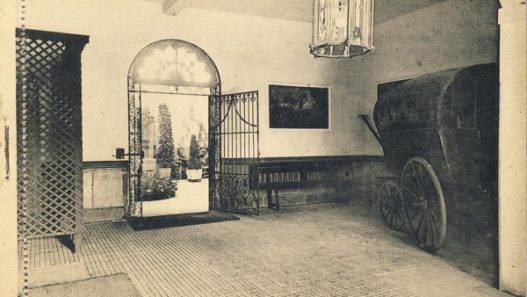

Thresholds as Ritual Stages: A hamam typically guides users through different spatial thresholds that prepare them mentally and physically for the communal bath. For example, a classic Ottoman bathhouse such as the 1584 Çemberlitaş Hamamı in Istanbul (attributed to the architect Sinan) has a carefully arranged sequence: one passes from the street through the camekân (the entrance hall where shoes are removed), then to the changing room (cold room), then to a warm intermediate room (warm room) to warm up, and finally to the hot steam room (hot room) where bathing takes place. This sequence of spaces—cooling zones, transitions to increasing heat and humidity—functions as a ritual of transition from the outside world to a collective inner sacred space. Traditional Japanese sento also similarly implement threshold rituals: shoes are removed at the genkan entrance, the person pays and passes through the bandai counter, undresses in the gender-segregated changing room, and then carefully washes before entering the hot bath. These stages are not merely practical; they signify psychological transitions from public to private space, from clothed to naked, from hurried to unhurried. Good design emphasizes thresholds with architectural cues: a change in flooring material to indicate shoes must be removed, a low ceiling or doorway to signal separation from the ordinary world, or framing elements (curtains, arches) that ceremoniously separate each stage.

Common Orientation and Visual Connections: In public baths, the spatial arrangement encourages strangers to focus on shared characteristics rather than each other’s nakedness. Dome ceilings with oculi (roof windows or holes), as seen in many baths, are a common strategy to create a calming and unifying atmosphere by drawing the bathers’ gaze toward the light entering from above. In the hot room of Çemberlitaş Hamam, a large central dome with small holes allowing daylight to seep in and a monumental central marble slab draw attention inward and upward, creating an almost spiritual feeling. On the other hand, in Japanese sento, wall paintings are often used as focal points: typically, a large image of Mount Fuji covers the bathing area, offering bathers a shared landscape to “lose themselves in thought” while bathing. This tradition of penki-e (wall paintings) is no accident—by providing a topic of conversation and a mental escape, it unites bathers in a shared visual experience. Contemporary architects have continued this tradition: for example, in Tokyo’s renovated Koganeyu bathhouse, artists were asked to create a panoramic Mount Fuji wall painting, so that even though separated by the wall, the artwork symbolically connects customers. These visual connections (domes, wall paintings, gardens visible from the windows, etc.) transform the bathhouse from a functional changing room into a public space.

Orchestral Light, Sound, and Warmth: A hamam uses sensory gradients to slow people down and synchronize them. Lighting is typically designed to be soft and indirect—for example, in traditional baths, light filters through small openings to create a dappled, “quiet” atmosphere. This not only preserves privacy with soft lighting but also signals visitors to lower their voices. Acoustically, historic bathhouses use plastered domes and vaults that trap and diffuse sound; some incorporate vaulted ceilings or strategic wall openings to prevent harsh echoes, keeping reverberation time comfortable and encouraging quiet conversation or meditative silence. Today’s designers can achieve a similar effect using acoustic panels or curved surfaces, ensuring that even tiled wet rooms are not unbearably noisy. For example, wooden slats placed over hollow voids or porous stone inserts can absorb sound while blending with the historical aesthetic. Thermal comfort is also carefully orchestrated: the best baths offer various water and air temperatures—for example, a hot pool, a cold plunge pool, a warm relaxation area—thus creating a cyclical ritual (warming up, cooling down, resting) that all participants can follow. This creates a rhythm: people sweat, cool down, rest together, and repeat; this synchronized pattern creates a subtle social bond. Environmental design must balance extremes: European standards such as EN 16798-1 define basic indoor climate parameters (typically comfortable room temperatures of ~20–25 °C and relative humidity of 30–70% for normal spaces), but bathhouses reach high humidity levels. Designers should define temperature and humidity set points by zone (e.g., hot room air 40–45°C and very high humidity, cooler relaxation rooms 25°C and moderate humidity) and ensure gradual transitions. Sufficient fresh air must be provided even in steamy areas (see Section 3 for more engineering details), but it should be done quietly and unnoticeably so as not to disturb the tranquility.

Civil Presence in the Urban Fabric: For a bathhouse to be truly civil, it must interact with the street and the community rather than hiding like a secret club. Many traditional bathhouses announced themselves with distinctive urban landmarks: the tall chimneys (from wood-fired boilers) in Japan or the ornate domes atop Ottoman bathhouses made them symbols of their neighborhoods. The contemporary public sauna Löyly, designed by Avanto Architects in Helsinki, reinterprets this idea by creating a striking sculptural form: the slatted “wooden cloak” enveloping the building serves as both an architectural sign and a functional screen. Löyly’s cloak filters the view (providing privacy for those bathing inside) while radiating a warm light to passersby, essentially “advertising” the ritual inside without revealing it. Furthermore, by creating public terraces and even stairs leading to an accessible roof, it returns public space to the city in the form of an urban amphitheater. Similarly, historic baths often featured public courtyards or staircases where people would gather before or after bathing. The front stairs and square of the Széchenyi Bath in Budapest serve as a social space. Designing a bath with a small square, bench, or café at its entrance can integrate the bath into daily street life, extending its purpose beyond those who pay to bathe.

Orientation and ritual flow: In a communal bath, first-time visitors should intuitively understand how to behave based on the order itself. For example, a classic Tokyo sento uses a symmetrical layout with a reception desk (bandai) in the center, allowing the attendant to see both the men’s and women’s sides. Although the genders are separated, there is usually an open space above the dividing wall or a shared wall painting, subtly reminding users of the parallel social experience. Visual axes usually end at important features (large wall painting, central pool) and guide visitors in the correct order. If the architecture is guiding, signage can be kept to a minimum: for example, the visibility of showers from the changing room ensures people wash before entering the pool, a tempered glass door shows beyond the steam and invites those ready to enter, etc. Designers should also consider adding ritual markers (e.g., a threshold stone or footbath at the entrance to washing areas) as cues indicating that certain actions (such as washing feet or removing shoes) should be performed. Such touches reinforce the common rules of bathroom etiquette architecturally, reducing the need for warning signs.

Thermal Environment and Air Quality (Criteria): While pursuing ambiance, the design must ensure comfort and safety in every area. Guidelines such as EN 16798-1 can be adapted for high-humidity areas: for example, keep the relative humidity in lounges around 40-60% (to prevent stuffiness), but it can go up to 80-90% in steam rooms; pay attention to material selection to prevent condensation. Temperature set points can be ~40°C for saunas, ~38–42°C for hot pools, and ~20–25°C for cooling areas. Ventilation is crucial: design for 4–6 air changes per hour in humid areas (higher if chlorinated pools are used) and use low-velocity airflow to prevent drafts. Engineering details will be provided in Section 3, but here, fresh air supply near the floor and high exhaust vents can help remove warm, humid air from breathing zones.

Acoustics (Design Details): Aim for a moderate reverberation time (e.g., ~1.0–1.5 seconds in warm rooms) to create a soft environment. Use architectural features to reduce noise: for example, install vaulted ceilings covered with porous plaster, place perforated wood panels behind counter areas, or add sound-absorbing material to suspended ceilings in changing areas. Control water sounds (fountains, taps) by using water features that mask harsh sounds with a soft trickle.

Architects who carefully combine elements such as threshold choreography, shared focal points, sensory gradients, and street presence can design bathhouses that serve as social rituals. A person enters the city, sheds their role and clothing layer by layer, and emerges cleansed and with a subtle connection to fellow citizens. In this way, the bathhouse becomes a microcosm of the community.

(Transition: After understanding how design can transform bathing into a social experience, we are faced with a practical question: Are there measurable benefits to this social ritual? The next section will explore whether bathhouses contribute to health and social well-being beyond nostalgia, and how their value can be demonstrated without reducing them to clinics.)

Non-Medicalized Health: Bathrooms as a Preventive Shared Resource

Design Thesis: Bathhouses, as part of public health and social infrastructure, can serve the function of promoting health and social cohesion, but this should be done without turning bathhouses into sterile clinics. Historically, communal baths served a daily preventive care function; regular sweating, washing, and socializing kept communities healthier. Today, evidence (mostly observational) is growing that practices such as saunas have cardiovascular benefits, and we know that social isolation has serious health costs. In this section, designers and planners explore how they can use data and policy recognition (e.g., UNESCO heritage) to justify incorporating bathhouses into modern cities by linking them to health outcomes and social inclusion. The challenge here is to leverage these benefits without “over-medicalizing” them – bathhouses should remain enjoyable and culturally meaningful spaces, not hospitals with hot water.

Evidence on Health Benefits: Over the past decade, researchers in Finland, where sauna-going is a way of life, have provided concrete data supporting the intuitive benefits of frequent communal bathing. A 20-year long-term study involving more than 2,000 middle-aged men showed that those who used the sauna 4-7 times a week had significantly lower rates of fatal heart disease and all-cause mortality than those who used the sauna once a week. The risk of sudden cardiac death was 60% lower among the most frequent sauna users compared to the least frequent users. These findings, published in JAMA Internal Medicine (2015), indicate a dose-response relationship: more frequent and longer sauna sessions are associated with better cardiovascular outcomes. Such studies cannot prove causality (people who regularly go to the sauna may also engage in other healthy behaviors), but they at least position the sauna as a health-promoting practice. Architects and bath advocates can use this type of evidence to support the argument that investing in communal bathing facilities is an investment in preventive healthcare. Imagine adding this to a project summary: “Research shows that regular sauna use is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular mortality rates; designing a public sauna can encourage healthy routines.” Similarly, hot springs (onsen) in Japan have been studied more qualitatively for stress reduction and circulatory benefits.

It is crucial not to turn the bathroom into a “prescription” or make excessive claims – otherwise, the pleasure and cultural richness behind people wanting to go to the bathroom may disappear. Instead, designers should subtly integrate wellness elements: provide areas for rest and hydration after a hot bath, incorporate nature (greenery or sky views) to enhance mental relaxation, and ensure accessibility so that the elderly or disabled can use the facilities (because they are the ones who will benefit from the therapeutic properties). Metrics to track or even measure in pilot projects could include average length of stay (a comfortable, long stay may indicate reduced stress), user-reported health scores, or community health statistics in neighborhoods with bathhouse access. Some contemporary bathhouses have begun collecting such data by partnering with universities or through user surveys to support the thesis that “a community that bathes together stays healthier together.”

Combating Loneliness and Building Social Capital: Beyond physical health, bathhouses have historically served as a “third place”—a neutral common space that encourages social interaction across age and class divisions. For example, in 19th-century Istanbul, women’s bathhouses were one of the few places where women could freely gather outside the home, serving as centers for matchmaking and information exchange. Japanese sento bathhouses were called “urban community living rooms” where intergenerational mixing was common. Neighborhood children, civil servants, and retirees could chat at the tap or drink milk after bathing. In today’s context of urban isolation, it is possible to argue that communal baths are an antidote to loneliness. How can we measure this? We can use some indicators for this: repeat visit rates (do regular customers form a community?), intergenerational participation (do young and old people come together?), and even surveys measuring whether customers feel a sense of belonging or social connection at the bathhouse. Some innovative projects also include additional programs: for example, the renovated Koganeyu in Tokyo not only offers bathing services, but also functions as a mixed social space by featuring a boutique beer bar and occasionally hosting events. By tracking event participation and cross-usage (do people stay to drink and socialize after bathing?), operators can measure the social impact.

Architecturally, designers are incorporating shared lounge areas or salons to support the element of social common areas. A good example of this is Finland’s public saunas, many of which feature a fireplace or café. Löyly in Helsinki has a restaurant and outdoor terraces specifically designed so bathers can cool off while sitting and chatting in their bathrobes. This extends the time for social interaction. In Japan, many modern super sento have relaxation areas with tatami mats and even libraries or TV rooms. This acknowledges that a large part of the experience is communal relaxation after bathing. In more traditional small facilities, even a modest seating area with water coolers or a small manga library can encourage people to linger and interact. The design of these areas should be inviting: warm lighting, comfortable (and waterproof) seating, perhaps a courtyard view. By making “hanging out” appealing, you foster the social fabric that is as much a benefit of public baths as cleanliness itself.

Policy Recognition and Cultural Value: Another way to support the argument that baths are valuable infrastructure is through cultural policy. Finland’s success in securing UNESCO recognition of “Sauna Culture” in 2020 is instructive in this regard. The UNESCO list emphasizes that the sauna is “an integral part of Finnish life… much more than just washing – a sacred space that cleanses the body and mind” and notes that it is a tradition easily accessible to all segments of society (3.3 million saunas for 5.5 million people!). This not only honors the heritage but also helps to protect it – this recognition could support funding for the preservation of historic saunas or the construction of new public saunas. Architects can draw on such examples: for instance, they could propose preserving a historic bathhouse not just as a building but as a living cultural practice. Budapest’s thermal baths, although not on the UNESCO list, are heavily promoted by tourism boards as culturally essential experiences; this civic pride has justified investment in the city’s upkeep (though, as we saw in the Gellért example, significant funding is still needed for renovation work). In Japan, local governments and NGOs are campaigning to save sento by declaring them “cultural assets” or at least emphasizing their role in social resilience (for example, some sento have offered free bathing services after disasters). Tokyo’s “WELCOME! SENTO” campaign defines bathhouses as cultural assets worth experiencing (and therefore preserving) by associating them with hospitality offered to foreign visitors. For designers, collaborating with cultural authorities or health departments can create funding opportunities. A bathhouse project can benefit from public health budgets if presented as a health center, or from cultural grants if linked to the preservation of traditions.

Health Metrics That Can Be Referenced: During the design phase, consider referencing health studies in your proposals: for example, “Frequent sauna use (4 times or more per week) reduces the risk of fatal heart disease by approximately 50%; the affordability of our saunas may encourage regular use by residents.” Use such statistics carefully, citing sources and providing supporting context. Also, suggest measuring post-use results: track usage frequency, average usage time, and user surveys regarding stress levels before and after bathing. This data-driven approach can validate health claims without turning the bath into a clinic.

Social Inclusion Criteria: The operator must record membership diversity (age ranges, gender balance on mixed days, etc.) and even encourage them to organize community days (such as weekly family bathing time or extended evening hours exclusively for women). Successful metrics—such as regular participation by seniors (indicating this is a safe place for them) or increased participation by young adults (showing cultural relevance)—can be provided to stakeholders as feedback demonstrating social impact. Even qualitative measures, such as friendships formed in the bath or stories of groups that meet regularly, can be very effective.

Bathhouses can justify their existence with measurable benefits—improved cardiovascular and mental health, reduced loneliness, the appeal of cultural tourism—but these should remain side stories to the main narrative of pleasure and relaxation. The design should never give the impression of a “health clinic”; health is a natural byproduct of a beloved social ritual. Architects can facilitate this by offering spaces that invite frequent and enjoyable use and subtly reinforcing healthy behaviors (such as showering before entering the bath, drinking water, cooling off appropriately). If public baths are valued and used frequently, they become preventive communal spaces—informal community hubs that keep people clean, connected, and happy, arguably as important (and much cheaper) for public health as hospitals.

Engineering Safety Without Disrupting the Atmosphere

Design Thesis: Modern bathhouses must meticulously address ventilation, water quality, and material durability to ensure health and safety. However, these engineering solutions must be carefully integrated so as not to disrupt the sensory ambiance. In the post-COVID world, public hygiene expectations are higher than ever: no one wants to be in a “stuffy” bathroom or breathe in the smell of chlorine. Regulatory bodies also demand strict humidity control to prevent mold and Legionella bacteria growth in water systems. The challenge for architects and engineers is to “hide the medicine” – that is, to integrate advanced HVAC, filtration, and materials science in a way that guests will hardly notice. This section summarizes basic safety engineering measures (referencing standards such as WHO spa guidelines and the CDC’s Model Aquatic Health Code) and how they can be designed to be compatible with architecture. When done correctly, a bathhouse can be clinically safe yet atmospherically rich; when done incorrectly, it results in a facility that feels like a sterile laboratory or, conversely, a moldy dungeon.

Ventilation and Indoor Air Quality: Humidity, heat, and chloramines (if there are chlorinated pools) are the biggest problems related to air quality. A common problem in older indoor pools is the intense chemical smell of chlorine (chloramine) mixture lingering on the water surface, which stings the eyes. We now know this is a sign of insufficient airflow over the water surface. To prevent this, design the HVAC system specifically to move air over the pools: ventilation openings should provide fresh (and ideally dehumidified) air from low points along the pool or tub edges and push stale air toward exhaust grilles placed just above the water surface. The CDC recommends, “Move fresh air across the water surface and toward air exhaust vents to prevent chloramine buildup on the water surface.” Therefore, instead of typical ceiling ventilation (which can cause chlorine gas to remain at ground level where people breathe), a well-designed bathhouse may feature perimeter venting around the edges of hot pools or low wall exhaust in saunas, allowing gaseous vapors to be continuously expelled. Fans and ducts must be sized appropriately for high humidity loads: corrosion-resistant materials (PVC or coated aluminum ducts, waterproof fan motors) must be used.

Another important point is maintaining negative pressure in wet areas compared to adjacent areas. For example, the pool room should have a slight negative pressure compared to the changing rooms, so that when the door is opened, humid air does not escape (this prevents condensation problems in cooler areas). This means that more air is extracted from wet areas than is supplied, and makeup air is drawn from dry areas. Climate standards can guide fresh air ratios: For example, EN 16798-1 classifies indoor air quality levels; a high-humidity steam room may require a level equivalent to Category IDA 1 or 2 (excellent or good air quality), which could mean an outdoor air supply of 10–20 liters/second per person. In practice, bathhouses typically require 100% outside air ventilation (without recirculation) to effectively remove moisture and smoke – energy recovery devices (such as heat exchangers) can preheat the incoming air by recovering heat from the exhaust, preventing energy waste.

The important thing is that all these machines are as invisible and quiet as possible. To reduce fan noise, position the air handling units away (e.g., on the roof or in a soundproofed plant room). Prevent hissing or drafts by using large, low-speed ducts and diffusers – bathroom users should not feel a cold airflow. Consider architectural integration: for example, continuous linear diffusers running along the top of walls that also serve as decorative projections or floor grilles that appear as part of the border pattern. When renovating historic bathrooms, creative solutions such as concealing ducts in countertop bases or using the space under raised tub bases for air distribution can preserve aesthetics. Modern sensors can be used to regulate ventilation – CO₂ and humidity sensors can speed up ventilation during busy times and slow it down when empty, efficiently maintaining air quality.

Water Quality and Treatment: If the facility has a pool or spa, the water must meet strict microbiological and chemical standards. This typically involves a combination of filtration, disinfection, and recirculation working invisibly in the background. WHO guidelines for recreational water recommend clear limits (e.g., residual free chlorine 1–3 ppm and pH approximately 7.2–7.8 in pools) and zero tolerance for pathogens such as fecal coliforms. The US CDC’s Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC 2023) provides a comprehensive plan for businesses; one of the emerging issues in recent years is chloramine control. To reduce chloramines (formed when sweat/urine mixes with chlorine), design should encourage/recommend pre-shower rituals (many bathhouses reduce water waste by placing **shower stations at the pool deck entrance as a final reminder). Some facilities even use attractive signage or fun incentives, such as a small “rain shower tunnel” that bathers pass through on their way to the main bath.

Filtration systems (such as sand filters) can be installed in the utility room on the basement level, but keep in mind that these systems typically require a significant amount of space and ceiling height. Secondary disinfection methods such as UV light units are becoming increasingly common to burn chloramines and kill resistant pathogens (e.g., Cryptosporidium); these can be installed in series after the filters. It is important for designers to allocate space and access for this equipment while ensuring it does not disrupt the pool environment. A good practice is to create a dedicated “back-end” wet plant area at the rear of the pool, perhaps concealed behind a wall forming the pool’s backdrop, to allow maintenance personnel to change filters or flush systems. Acoustically isolate pump rooms (with concrete walls or vibration dampers) so that the hum of the pumps cannot be heard.

Legionella (a bacterium that can multiply in warm stagnant water and cause Legionnaires’ disease when inhaled through droplets) should be prevented by ensuring there are no stagnant corners in sanitary plumbing systems. This means preventing “dead legs” with continuously circulating hot water pipes and periodic high-temperature flushing. If features such as misting systems or steam rooms are present, ensure they are also subject to regular cleaning and flushing programs. Many building codes today require a Water Safety Plan for facilities with hot water systems. Architects can coordinate with mechanical engineers early on to map all piping, storage tanks, etc., to minimize risk points. Sometimes architectural changes can also help, such as sloped ceilings to prevent water accumulation and good ventilation in steam rooms.

Another important consideration is materials and surface finishes: surface selection is crucial for safety in wet areas. Slip resistance is very important; modern non-slip ceramic tiles or textured stones should have a minimum R11 or higher slip resistance rating. Epoxy grout (instead of cement grout) prevents mold growth in joints. All wood used in these areas (sauna benches, etc.) should be rot-resistant and preferably heat-treated to prevent warping. Designers can specify drainage slopes (typically a 1-2% slope towards drains) to prevent water pooling and add ample floor drainage (with cleaning holes) to corners where water may accumulate.

Protecting the Atmosphere: Precision is crucial in all these systems. Historically, bathhouses featured smart passive designs: for example, high domes collected warm, humid air and released it through small, openable domes. We can replicate some of this—for instance, if the bathroom ceiling is high, you might consider using a hidden roof vent or an openable skylight that can naturally vent moisture when the weather permits. Daylight must be balanced with insulation; double-glazed skylights can provide iconic light shafts (like hammam oculi) without significant heat loss. Vapor barriers are essential in walls and ceilings, but they can be invisible. Ensure the continuity of the vapor barrier to prevent invisible condensation in the structure. This usually means carefully detailing around openings (e.g., around a light fixture or speaker installed in the ceiling of a steam room; these areas should be sealed and made airtight).

To avoid a clinical feel, steer clear of overly bright white, hospital-like surfaces. You can meet hygiene requirements with natural materials: for example, stone-effect porcelain tiles or properly processed real stone. Copper and brass fixtures are naturally resistant to bacteria and give a classic look, aging gracefully over time (used in many traditional baths, such as golden faucets). By complying with WHO water standards, you can pump water into a beautiful marble sink and allow bathers to splash water as they did in the old days. Behind the sink, the plumbing provides perfectly sterilized hot water, while the user simply enjoys the waterfall.

Another engineering safety measure is preventing condensation in unwanted areas (to prevent structural damage or mold formation). The building envelope surrounding a wet bathroom must be well insulated on the warm side to keep the interior surfaces above the dew point. In practice, for example, in a warm room with a temperature of 40°C and a humidity level close to 100%, the dew point is approximately the same (~40°C!). Exterior walls or ceilings adjacent to such a room should be vapor-proof or insulated from the outside. Generally, the best approach is to create an inner shell: for example, constructing the warm room as a room within a room, leaving a ventilated or at least heavily insulated cavity to ensure that the humid air never comes into contact with the cold exterior surface. The vaulted stone domes in old bathhouses performed well because they were thick and had thermal mass, keeping the interior warm. In modern buildings, closed-cell spray foam can be used on the outside of the steam room ceiling (if concealed behind a suspended ceiling), or a membrane can be placed between wall layers. Detail all joints (wall-floor, etc.) with waterproof tape so moisture cannot seep into cracks. These “invisible” details do not directly affect the ambiance, but they are crucial for longevity – a damaged, moldy bathhouse will be closed, and this will certainly ruin the atmosphere.

CDC MAHC Key Points: Ensure continuous water circulation at an adequate turnover rate (for example, hot tubs typically require a full water turnover in less than 30 minutes). Use automation for chemical dosing (modern systems can detect and adjust chlorine and pH levels) – this ensures safety without constant staff intervention. MAHC also recommends design interventions such as UV systems for chloramine control and maintaining air humidity ideally around 50-60% in pool areas to balance comfort and pathogen control. Maintaining 50-60% relative humidity in hot bath rooms can be challenging, but it is possible in surrounding areas and prevents mold growth in cabinets.

Processes and Rituals: Design for easier maintenance: for example, sensor-operated faucets and showers reduce water waste and touch points (post-COVID, touchless is preferred). However, don’t let technology completely replace tradition – some cultures prefer manual faucets (like pouring water from a pitcher in bathhouses). A compromise: perhaps modern showers and traditional sink faucets can be used together. Also consider staff visibility – attendants should be able to see most of the facility (or monitor remotely via cameras) and quickly spot unsafe behavior or spills. Strategic glass or low partitions can provide this without compromising privacy when needed.

In short, 21st-century bathhouses can meet the highest health and safety standards while offering an inviting relaxation environment. The secret lies in collaboration between architects and engineers at an early stage: aesthetics and building systems must be designed together, so that channels can elegantly curve around vaults, filters can be concealed beneath benches, and sensors and pipes can be embedded in walls before being covered with tile mosaics. Bathhouse users should only feel the refreshing air, sparkling water, and pleasant warmth—all safety mechanisms should fade into the background. When technology and design work in harmony, the result is a safe haven: you breathe easy (literally, there is no chlorine smell), you trust the water, yet you remain blissfully unaware of the sophisticated life support systems that keep this little paradise running.

(Transition: Our ideal bathhouse, where design and engineering are in harmony, is a public and healthy space. But can it remain economically viable? Next, we will address the cold realities of the business, such as energy bills, revenue sources, and how creative programming can subsidize the true cost of public bathing services.)

Water and Heat Economy: How Can Bathrooms Pay for Themselves?

Design Thesis: To succeed in modern cities, bathhouses must adopt sustainable business models and multi-purpose programs. Architecture should facilitate a “mixed economy” that provides affordable and culturally inclusive bathing services, cross-subsidized by other revenue streams. Traditional bathhouses have faced financial difficulties due to high fixed costs (fuel, water, personnel) and admission fees that are often kept low for accessibility, as bathing has ceased to be a daily necessity. The reason many baths have closed today is operating costs and lack of revenue diversity. This section examines models where baths are combined with complementary uses (cafes, bars, cultural venues) or utilize unique energy sources (such as natural hot springs) to reduce operating costs. The design should support these mixed uses without compromising the bathhouse’s core function. We will examine contemporary examples such as a sauna in Finland that also serves as an event venue, a renovated Tokyo sento with a craft beer pub, and a geothermal hot spring park in Chile that utilizes geothermal heat as prototypes for financial feasibility.

Hybrid Programs – Bath + Dining + Culture: A successful approach is to combine the bath experience with dining and entertainment to attract a wider audience and generate additional revenue. Helsinki’s Löyly is the best example of this: it houses both a public sauna facility and a restaurant/bar in the same building. Visitors can purchase a sauna ticket and enjoy food or drinks within the facility, making it an attractive destination for both frequent sauna users and casual tourists who come just for the architecture and a cocktail by the sea. The building’s striking design—wooden “cape” terraces—actually serves as an amphitheater and viewing lounge, and even those not using the sauna can come up here to enjoy the view or sunbathe. This means that part of the bathhouse is a public space, which increases the venue’s popularity and visitor numbers. Revenue from the restaurant and events (Löyly’s roof has hosted small concerts and yoga sessions) helps cover the sauna’s operating costs (which typically have a lower profit margin). In terms of design, Avanto Architects had to ensure that wet and dry areas did not overlap: they separated the sauna area (with its showers and hot rooms) from the restaurant with careful circulation routes, acoustic buffers, and an intermediate lounge. However, they ensured that the sauna and restaurant remained connected enough to allow easy passage (in appropriate attire) from one to the other. Thus, the architecture can encourage people to extend their stay (and spend more) – for example, by providing comfortable transition areas where they can sit after bathing, sparking the thought, “I’m relaxed now, how about a drink or a snack?”

In Japan, a new trend called renovated sento is trying similar tactics on a smaller neighborhood scale. Tokyo’s Koganeyu, which reopened in 2020 after renovations, retained its core bathing function while adding a craft beer bar in the lobby and a DJ booth for occasional music events. Essentially, it can function as a community bar at night (customers can hang out in yukata robes after bathing). Designed by Schemata Architects, the renovation creatively repurposed unused spaces (such as turning the old boiler room into part of the bar) while preserving the original layout. This attracts younger customers who might not normally visit a sento, boosting revenue (through beverage sales). Another example in Tokyo is Komaeyu. A once-dilapidated bathhouse has been transformed into a retro-cool venue featuring handmade sodas and live music nights. This example demonstrates that even modest bathhouses can become local cultural hubs.

Architecturally, the following considerations must be taken into account to enable this type of mixed use: providing seating and gathering areas where people can spend time, ensuring that the kitchen or bar located near the bathing area complies with regulations (proper air separation, etc.), and creating an environment suitable for both uses (for example, the designers of Koganeyu used modern lighting and artwork so that the sento could continue to be used as a bath during the day while also feeling sufficiently stylish as a nighttime venue). Entrances can be divided into sections: for example, one entrance for bath users and another for those coming only to the cafe, or an arrangement that locks the baths outside operating hours while keeping the lounge open for events. Flexibility is crucial: the architecture can incorporate movable partitions or signs to switch the space from “bathroom mode” to “event mode.”

Energy and Resource Innovations: In terms of cost, water and room heating is the largest expense for bathhouses. Traditional Japanese sento used to burn large amounts of wood or oil to heat water; today, gas or electricity bills can be very high for large facilities. Budapest’s thermal baths are fortunate to be located on top of natural hot springs. Geothermal water gushes out in bubbles at high temperatures, reducing the need for heating, which is a major advantage. Some facilities in other regions are experimenting with modern geothermal heat pumps or rooftop solar panels to preheat the water. Architects should investigate local conditions: Is there a way to connect to a district heating system? Is there a nearby source of industrial waste heat? For example, a creative proposal in Helsinki suggested using excess heat from data centers to heat a public pool. A small-scale step is heat recovery from wastewater: Warm water from bathtubs/showers can be passed through a heat exchanger to preheat incoming cold water and save energy.

One of the most striking examples of using natural energy is Termas Geométricas in Chile. Located above volcanic hot springs, this facility has eliminated boilers by using geothermal water flowing through the facility. Architect Germán del Sol designed minimal infrastructure: red wooden walkways connecting 17 hot spring pools stretching along the canyon. There is no complex pump system to carry the water upwards; instead, the design follows the valley’s downward flow – hot water emerges from the ground and is transferred from pool to pool by gravity, then exits via a stream. This gravity-fed system saves pumping energy and takes advantage of nature’s offerings. Hot springs are not found everywhere, but the principle is to use passive design and context. Termas Geométricas also uses wood-burning stoves to heat the rest pavilions along the walkways (the fireplaces provide warmth and create a cozy social gathering spot). The architecture embraces rustic simplicity to keep maintenance easy: locally repairable wooden structures and limited electric lighting (night visits are done with lanterns, which reduces electricity use and adds charm).

When natural energy is unavailable, another approach is load management. Since most people take showers in the evening, heat and electricity demand peaks during these hours. Architects can help by designing thermal storage systems. For example, large insulated hot water tanks can be used that are continuously heated during times when energy prices are cheaper (at night or during the afternoon) and store this heat for periods of high demand. This requires space allocation (e.g., a tank room under the terrace or in a back corner). Similarly, insulating pools or covering them with covers during closed hours to retain heat could also be considered.

Financial Models and Pricing: Most traditional bathhouses were very inexpensive (some still are—for example, the entrance fee for Tokyo’s sento is set by the government at 500–600 yen (approximately $4–5)). While this low price is great in terms of accessibility, it means that revenues may not cover costs, especially if customer numbers decline. Therefore, cross-subsidization is crucial: “dry” revenue supports “wet” activities. Tiered pricing can also help: for example, premium services (private sauna rooms, private tubs, or massage treatments) can be offered at higher prices to effectively subsidize the basic bath fee. Many Korean jjimjilbang (spa complexes) implement this: the general admission fee provides access to communal baths and sauna rooms, but private scrubs or private saunas incur an additional charge.

From an architectural perspective, providing separate areas that can generate income is a smart approach. Löyly has private sauna rooms that groups can rent. A small massage or treatment room can be found in a bathhouse; when not in use, it can serve as a quiet relaxation room, but when a masseur is on duty, it can be a source of income. Multi-purpose rooms allow for rentable events (yoga classes in the morning, community meetings in the evening). When designing such spaces, include the necessary infrastructure (e.g., sound system, flexible seating arrangement, mat/chair storage area).

Public Support and Partnerships: Not all values can be directly converted into money – some bathhouses may be supported by public subsidies because they provide social benefits (as discussed in Section 2). If a city administration can prove that a bathhouse serves a certain number of elderly or low-income citizens, it can cover rent or public service costs. For example, in Japan, some neighborhoods implement subsidy programs to help sento operators with fuel costs, recognizing their cultural value. Architects can assist customers by designing inclusive features (such as accessibility and community rooms) that strengthen the case for public funding. Additionally, partnerships with gyms or healthcare providers can be explored—for example, a physical therapy clinic could be opened next to the bathhouse (the clinic could pay rent, and patients could use the bathhouse as part of their treatment, ensuring a steady flow of customers).

Program Layering (Diagram Concept): Visualize the facility’s functions and revenues in a layered diagram. For example, ground floor: bathhouse (entry fee, low profit but necessary); second floor: cafe (higher profit margin); top floor: open lounge (free entry, but increases cafe sales and visibility). Show energy and cash flows. A proforma table could show that the bathhouse itself operates at nearly break-even, but “dry” programs generate 30% additional revenue, making the entire operation sustainable. Conversely, these programs also have costs—kitchens require staff, etc. Therefore, the mix must be balanced according to local demand.

Load Management (Metrics): Monitor peak loads and design accordingly. In situations where peak loads occur in the evenings, you can offer morning discounts to spread usage. If energy is the main cost, invest in efficient boilers or solar panels sized for the base load (e.g., to cover 30% of the heating requirement “for free”). Ensure the building management system can intelligently control temperature—for example, avoid overheating pools when unused. Consider water usage: low-flow showerheads and graywater reuse in toilet flushing can reduce costs. These are all technical measures, but architecture can also facilitate them (space for separate graywater tanks, etc.).

In summary, for a bathhouse to become financially sustainable by 2025, entrepreneurial programming and sustainable design are required. The architect’s role expands to coordinate the integration of different uses and anticipate operational strategies. The bathhouse can no longer be a single-purpose structure open 4-8 hours a day just for bathing; it must be a all-day venue that can serve morning bathers, lunchtime café-goers, those seeking a shared workspace in the afternoon (why not a quiet lounge?), evening spa users, and weekend family gatherings. By designing flexible spaces and ensuring that additional features do not compromise the core bathing experience, we can create a place that is both culturally rich and economically resilient—a bathhouse that nourishes minds, bodies, and perhaps even stomachs, while covering the costs of water and heating.

Design for Dignity and Inclusion

Design Thesis: Public baths can function as social infrastructure only if they are respectful and inclusive of all participants. Public baths have historically served specific demographic groups (often segregated by gender, sometimes excluding certain classes or foreigners). When redesigning them today, architects must ensure that bathhouses are accessible to people with disabilities, embrace people from different cultures, and can be adapted to various comfort levels in terms of privacy and modesty. This involves complying with universal design standards (such as ISO 21542:2021 for accessibility) while also creatively meeting cultural expectations (such as providing separate times or areas for different genders and offering a clear code of conduct guide for newcomers). We need to create an environment where no one feels unsafe or humiliated. This includes thoughtful arrangements for changing areas, facilities for families, and design elements that provide privacy without compromising the communal atmosphere.

Accessibility (Universal Design): A modern bathhouse should be adapted to accommodate wheelchair users, individuals with limited mobility, visually or hearing impaired individuals, etc., and should ensure that as many people as possible can enjoy this experience. ISO 21542:2021 provides comprehensive requirements for accessible built environments and covers everything from pathways and ramps to door hardware and alarms. Some important points to apply in the context of bathhouses:

- Entrances and Pathways: The facility must have step-free access. If steps are present (most old bathhouses have large staircases), add a ramp or at least an inconspicuous wheelchair lift. Inside, all main circulation routes (to lockers, pools) should have wide, clear paths for wheelchairs (at least ~90 cm wide, preferably more). Non-slip, tactile flooring is very important (surfaces that are safe for bare feet but detectable with a cane).

- Changing Rooms: accessible changing cubicles must be included – with extra space for a wheelchair user and an assistant, benches, and grab bars. Floors should be level from the changing room to the shower and pool. Transfer benches should be located at the pool edge, allowing wheelchair users to transfer from their wheelchair to the benches and slowly enter the water. Better still, at least one pool should have a pool lift or ramp for those unable to use stairs. Many new spas are adding a gently sloped entry (beach-style or with handrails) to the hot tub.

- Support fixtures: Grab bars in key locations – for example, next to jacuzzi steps, in showers, next to toilets. These should create a visual contrast with their surroundings (ISO standards emphasize visual contrast for visually impaired individuals). For example, a dark-colored handrail in front of a light-colored tile wall. Additionally, tactile strips located at the top of stairs or where flooring materials change can alert visually impaired users.

- Sensory considerations: Good lighting and acoustics are beneficial for everyone. Avoid very dark corridors or excessively bright lights. Use visual alarms (flashing fire alarm indicators) for the hearing impaired and audible signals (a soft water sound to indicate the location of showers, etc.) for the visually impaired. Signs should be equipped with Braille alphabet and internationally recognized symbols (e.g., signs indicating male/female sections or “no diving” pictograms).

- Surface temperatures: An important point to note – to prevent individuals with neuropathy from experiencing burns or discomfort, ensure that exposed metal surfaces in sauna areas (such as grab bars and benches) overheating and other areas overcooling. Use wood or laminated materials for seating in hot areas.

By designing to standards, we not only fulfill our legal obligations, but also protect users’ dignity – a person with a disability should not face difficulties or be treated as second class. Consider an accessible route where a person using a wheelchair can reach the warm pool from the entrance via a gentle ramp. These individuals can enjoy using the bathroom independently, which empowers them. Most older bathrooms have been renovated with impractical solutions (e.g., portable pool lifts that are rarely used because they are difficult for staff to operate). If possible, integrate accessibility from the outset: for example, one of the pools could have a shallow entry and function like a large accessible bathtub.

Privacy and Comfort Between Genders: Cultural norms regarding nudity and the mixing of genders vary greatly. In Japan, bathhouses are traditionally separated by gender and used completely naked; similarly, there is separation in Korea; in contrast, Nordic saunas are generally mixed and naked (though culturally normalized), while in some places swimwear is mandatory. Flexibility is crucial when designing for inclusivity. One strategy is scheduling: the facility can set aside specific hours or days for women and men, as well as mixed family hours. Architecture can support this with separate sections that can be combined or divided. For example, many historic baths are “double” – consisting of two mirrored halves for men and women. A modern facility can often be designed with two wings operated separately by gender, but a movable partition or a dedicated “family sauna” area can allow mixed use at certain times. Signage and directional cues become crucial when modes change – clear signs indicating an area is closed to a group, etc.

Maintaining dignity in a socially exposed environment also means ensuring visual privacy. Open shower rooms and communal pools are inherently public spaces, but there are some design tricks: use frosted glass or curtained partitions in changing areas to ensure customers cannot see each other completely while undressing. Provide a few private shower stalls or curtain-enclosed changing booths for those who are shy or require privacy for medical reasons—this encourages people who might otherwise miss out on the experience. However, avoid converting the entire area into enclosed stalls (this eliminates the social aspect); the goal is to offer options within the environment. The Japanese sento model interestingly includes a centrally located attendant (bandai) who can visually monitor the changing areas for both genders (traditional bandai are elevated and can see into the changing rooms). Originally used for security and fee collection, this system may be considered intrusive today; many modern sentos have eliminated direct views of the changing areas by using cameras focused on entrances for security. It’s a balance: ensuring safety (preventing inappropriate behavior) without people feeling watched. Modern bathhouses may use hidden staff circulation routes with one-way viewing windows, or assign well-trained female staff to the women’s section and male staff to the men’s section for quick intervention if problems arise.

Cultural Sensitivity: If you are in a multicultural city or serving tourists, you may encounter visitors unfamiliar with local bathroom customs. This can lead to discomfort or embarrassment. A thoughtful design approach is to use informative signs or artwork that gently educate. For example, small diagrams on the wall could show “Step 1: undress, Step 2: shower, Step 3: enter the bath.” Tokyo’s “WELCOME! SENTO” campaign did this explicitly, using multilingual signs and graphics to guide foreign guests. These should be placed at decision points (such as near the lockers or shower area). Additionally, providing rental clothing or towels helps those without appropriate items; for example, some foreigners visiting Finnish saunas may not know they need to bring a towel to sit on – the facility can have these ready.ilir.

For modest communities, consider alternatives to nudity: some modern facilities allow swimsuits or towels to be worn in mixed areas. Design can address this need with a drying area for swimsuits or by using water-resistant materials (if people wear clothes, water fibers will be carried to the filter, so adjust filtration accordingly). Family rooms (rooms where parents can bathe with children of the opposite sex in privacy) are another inclusive feature – perhaps next to the main bathrooms, there could be a small private tub room that people can reserve.

Safety and Harassment Prevention: Unfortunately, any shared space can be misused. To ensure everyone feels safe, eliminate hidden dark corners in wet areas where inappropriate behavior might go unnoticed. While providing semi-private niches (for comfort), use layout and lighting to avoid completely isolated blind spots. Regular patrols by staff (with appropriate courtesy) can prevent inappropriate behavior. In some Japanese sento, women in their 70s or 80s are employed as attendants in the men’s bath (a traditional practice) to ensure politeness is maintained. While this is an interesting cultural feature, it is not a comfortable practice for everyone. In any case, staff training and the presence of staff are part of the design, as it is necessary to provide scenic and quick access to staff areas.

Examples: Let’s revisit Çemberlitaş Hamam – this bathhouse was designed from the outset as a dual-gender bathhouse, taking into account the gender norms of its time. The bath is still segregated by gender, but its architecture (massive stone walls between sections) prevents interaction between genders; in a more contemporary design, with the use of timing, such a strict separation might not be necessary. On the other hand, the Széchenyi Bath in Budapest has mixed outdoor pools, but the indoor sections are separated by gender; swimsuits are mandatory in the mixed areas. Its design combines large communal pools with smaller, separate niches, allowing users to choose the area where they feel most comfortable.

Another issue is the inclusion of transsexuals and people who do not conform to the binary gender system, a modern problem that was rarely addressed in old bathhouse cultures. Ideally, a facility can provide a comfortable option for people who do not conform to the binary gender distinction. This can be achieved through private changing rooms or specific “all genders” sessions. Design alone cannot solve cultural issues, but some private changing cabins and signs such as “use the area where you feel most comfortable” can help. Private, rentable bathrooms can also serve those who do not feel comfortable in either section but still want to experience this.

ISO 21542 and EN 17210 (Accessibility Standards): These standards include minimum door opening width (e.g., 850 mm), ramp slope (preferably maximum 1:20), etc. They also specify the justifications for the areas necessary for people to safely “approach, enter, use, and evacuate” buildings. Paying attention to evacuation in the bathroom is important – ensure that even wheelchair users can quickly get out in an emergency (this may mean having evacuation chairs on site and wide exit routes). Use contrasting colors for the edges of pools or steps (for example, a dark-colored, decorative yet safety-oriented tile border around the edges of a light-colored pool floor). These details show that care has been taken for all users.

“Privacy Gradient” Design: One approach is to create a gradient within the bathroom from public areas to private areas. For example, entrance lobby (completely public, mixed, clothed) → changing room (semi-public, single-gender, partially clothed) → bathing hall (communal nude, but specific to that group) → optional secluded corners (such as a quiet jacuzzi in the corner for those who want to be less visible). By designing various spatial scales, you enable people to participate at a level where they feel comfortable. Even in a large pool, some corners or edges protected by columns or plants can provide a bit of personal space.

Honorable design involves putting yourself in the shoes of all potential users and asking, “Would I feel comfortable here?” Have the necessary precautions been taken for my privacy needs? If I have a disability, can I move around without feeling embarrassed or needing help? The goal is for everyone to be able to leave not only their clothes but also their labels from the outside world behind equally after entering the water or sauna, and to feel like people who are simply enjoying a shared experience of cleanliness. For this, the invisible hand of design is necessary to ensure that no one is excluded or discriminated against.

If we can achieve this – an elderly regular, a tattooed young tourist (tattoos are another matter in Japan ), a disabled person, and a family with children can all feel comfortable – then the bathhouse will have fully realized its potential as a social infrastructure. It becomes a rare space in modern life: a place that brings people together in their most human states and, by doing so in a carefully designed, safe, and beautiful environment, indirectly teaches empathy and equality.

Revitalization of the Public Bathhouse

Public baths, in their ideal form, are microcosms of civilized society – places where people from different backgrounds come together, stripped of pretense (and their clothes), participating in a ritual that is both ordinary and profound. As we have previously examined, these spaces are disappearing in many parts of the world under the pressure of modernization, economics, and changing lifestyles. Paradoxically, however, the very elements that threaten bathhouses—private bathrooms, digital isolation, sterile modernity—are also the reasons for their revival. In the urbanized, stressful world of 2025, it can be said that the need for physical social experiences and affordable healthy living is greater than ever. Architecture, combined with smart planning and policies, can be the catalyst for rediscovering bathhouses in this era.

Throughout this report, we have identified five issues that need to be addressed in the renovation of communal hygiene areas:

- Urban Design: Architecture, spatial arrangement, shared symbols (domes, wall paintings), and atmosphere can transform bathing into an urban ritual. From Tokyo’s Fuji Mountain wall-painted sento bathhouses to Istanbul’s domed bathhouses with skylights, we can see how design harmoniously brings together the slowing of time and the feeling of togetherness. New projects should continue this; they should turn baths into symbolic structures and shelters, not hidden service rooms.

- Health and Social Value: Public baths contribute to public health and the strengthening of social bonds. We have evidence supporting the health benefits (e.g., Finnish sauna studies) and countless examples demonstrating social cohesion. By positioning bathhouses as part of the preventive health infrastructure and cultural heritage, we can secure funding and public support. This must be done while preserving the elements of pleasure and leisure at the heart of the experience – a bathhouse that is not enjoyable will fail, regardless of the health data.

- Safety Engineering: Modern bathrooms can and should be hygienic and safe environments. Advances in HVAC and water purification allow us to eliminate old problems (stuffiness, mold, infections) without turning the space into a clinical room. The best contemporary bathrooms quietly blend technology with tradition – you can relax by a “historic” pool, unaware that in the basement, a state-of-the-art UV filter and heat recovery unit are working to keep your water warm and clean. Designing these systems from the outset ensures that safety enhances comfort (clean air, clean water).

- Economic Sustainability: The bathhouses of the future will likely not be able to survive on bathhouse tickets alone. They will be mixed community centers that are partly bathhouse, partly café, partly health center, and partly tourist attraction. This multifunctionality is not a compromise, but a strength that keeps the spaces active and financially viable. Architectural creativity is needed to seamlessly blend these functions. Löyly’s sauna-bar or Koganeyu’s sento-pub show that it is possible to pay respect to bathhouses while also offering fun programs. Meanwhile, environmentally conscious design (such as utilizing natural hot springs or solar energy) can reduce operating costs. A sustainable business model is as important as good design, and architects are increasingly collaborating with clients when designing these models (for example, incorporating rental event spaces or retail corners into the design).

- Inclusivity and Dignity: Finally, a truly “public” bathhouse must embrace the public in all its diversity. This requires every effort to eliminate physical and social barriers. Accessibility features based on universal standards provide equal access to relaxation and healing opportunities for people with disabilities. Cultural sensitivity in design and operation transforms local bathhouses from exclusionary places into spaces for intercultural exchange. Simple design choices—a special shower here, a separate family tub there, clear signage everywhere—can make a big difference in how comfortable visitors feel upon entering. In a way, shared bathhouse design is the reflection of empathy in walls, floors, and fixtures.

By bringing these threads together, we envision the 21st-century bathhouse as a revitalized public institution: perhaps not as widespread as before, but beloved and well-used wherever it exists. This could be a new building in the city center that is modern but bears traces of historic baths, or an old bath that has been carefully renovated with contemporary amenities. In Europe, this could mean reinvesting in the thermal baths of cities like Budapest as important urban infrastructure (like parks or libraries). In Japan, it could mean a new wave of stylish sento baths that attract young customers (we are already seeing designers, artists, and entrepreneurs collaborating on this). In Latin America, it could take the form of eco-resort baths (like Termas Geométricas) that make bathing in nature accessible and popular, encouraging local communities to value their natural thermal resources.

The lesson for architects and planners is this: design matters at every level: sensory details (warm tiles underfoot), functional flow (can a person using a wheelchair move freely?), sustainability (will this bathroom bankrupt itself with energy costs?), and cultural narrative (does this place tell a story that speaks to people?). When all these layers are considered, a hamam can transcend being merely a “place to wash” and return to its original purpose: a place of social equality, relaxation, and a cornerstone for the community.

By preserving and recreating these spaces, we are not chasing the nostalgia of “the good old days”; we are responding to the needs of today: communities that need to connect, people who need unpretentious health and wellness, cities that need public spaces where real interaction takes place. The death of communal hygiene is not inevitable; on the contrary, it can be reborn with imagination and determination. UNESCO’s recognition of sauna culture and the excitement surrounding new bathhouse projects signal a global revival. Together with architects, city officials, and local advocates, they can transform this spark into a warm, steamy glow that illuminates our cities—one bathhouse at a time.

Whether in a stylish Scandinavian sauna with glass walls overlooking the forest or in an ornate Middle Eastern hammam where whispered conversations echo, the essence remains the same: human bodies, together with one another, purify and renew themselves in a space where they are cared for. Designing for this essence is both a challenge and a reward for us—it means not just constructing a building, but creating a collective human experience that is becoming increasingly rare and valuable in our fragmented modern world.