Architecture is never neutral. Buildings, streets, and infrastructure direct power, signal alliances, and make political projects inevitable. From imperial boulevards to secure embassies and branded museums, space becomes a stage where states and markets display their authority. Critical theorists have shown that space is not merely occupied, but also produced and managed. Therefore, architectural form is often read as a map of geopolitical intent.

Geopolitical thinking has entered design culture in various ways. While classical geopolitics framed land and resources as strategic assets, twentieth-century social theory explained how space disciplines bodies and the imagination. These two currents coming together help us read urban plans, monuments, and infrastructure not only as works of art but also as instruments of power.

Today’s designers also work within non-state systems that operate beyond the official government. Special economic zones, logistics parks, and cultural franchises create an “infrastructure space” that quietly governs daily life. Understanding these environments is crucial to grasping how contemporary geopolitics materializes on the ground.

Historical Context and Theoretical Foundations

Geopolitical architecture has deep roots. Nineteenth-century powers used urban renewal to consolidate control within their own countries and empires. For example, Baron Haussmann’s Paris reorganized circulation and visibility in ways that many scholars interpret as social engineering and crowd management as much as beautification.

Twentieth-century theory provided a language for analyzing how space is produced and controlled. Henri Lefebvre argued that space is a social product that shapes practices and perceptions. Michel Foucault used the panopticon as a model of power that sees without being seen, explaining how spatial arrangements enforce discipline. These ideas retain their fundamental quality for reading the city as a political technology.

On a global scale, classical geopolitics has emphasized strategic geography. Halford Mackinder’s Heartland thesis and subsequent theories have treated land, sea, and chokepoints as determinants of power. These abstractions have been reflected in planning, from the location of capitals to the design of transportation corridors.

The origins of geopolitics in architectural discourse

Architects and planners first embraced geopolitics through imperial urbanism and security-focused planning. Haussmann’s long vistas, wide boulevards, and sanitized neighborhoods enabled rapid troop movements and surveillance while maintaining order. This fusion of urban design and state governance created a template for subsequent capitals.

Modern theory has clarified this issue more clearly. James C. Scott demonstrated how states ensure “readability” by standardizing land, addresses, and grids. This facilitates administration while making opposition more difficult. From a design perspective, cadastral surveys, urban planning, and rationalized street networks become tools that align daily life with central authority. Eyal Weizman later revealed how walls, roads, and checkpoints in the occupied Palestinian territories function as tactical architecture, transforming planning elements into instruments of control.

Towards the end of the twentieth century, globalization reshaped the urban landscape. Saskia Sassen’s thesis of the global city redefined cities as command centers where advanced services were concentrated, pulling architecture into the orbit of finance and diplomacy. Cultural flagships and airports became instruments of soft power, while skyline branding replaced geopolitical objectives.

Important theorists and their influence on spatial thinking

Halford Mackinder argued that controlling the “Heartland” of Eurasia could alter global power dynamics by expanding strategy to a planetary scale. Whether we accept his determinism or not, this thesis influenced thinking about corridors, bases, and inland capitals, which in turn shaped architectural programs for parliaments, ministries, and infrastructure.

Henri Lefebvre’s claim that space is socially produced shifted attention from objects to processes. For architects, this means that plans and sections are never purely technical drawings. They encode the relationships between institutions, labor, and daily rhythms, and can either reproduce inequality or create new civic possibilities. Michel Foucault’s explanation of surveillance and discipline explains why schools, prisons, hospitals, and barracks look the way they do and why visibility, circulation, and thresholds are politically significant.

Saskia Sassen’s global city framework explains why certain areas have dense clusters of banks, law firms, and media companies, and why these clusters demand specific spatial types: super-tall headquarters, retail floors, secure data centers, and luxury housing for elite labor. Keller Easterling expands on this with the idea of “infrastructure space,” showing how repeatable spatial formulas such as districts, ports, and logistics parks function as actual governance.

Architecture as materialized political power

Authoritarian regimes have long used monumentalism to convey the permanence of power. In Albert Speer’s plans for “Germania” and the Nazi Party Rally Grounds, massive axes, domes, and processions were used to choreograph obedience. Soviet monumentalism similarly sought to reflect collective power and central authority across the union by combining classicism with industrial motifs. These projects demonstrate how scale, symmetry, and parade ground areas can serve an ideological agenda.

Post-colonial nation-building transformed power into new capitals. Brasília’s Plano Piloto and Chandigarh’s Capitol Complex embodied political modernity through concrete and geometry. In Brasília’s Three Powers Plaza and Chandigarh’s Open Hand, form symbolizes a new civic order, while the plan imposes a spatial logic for governance. These were not merely aesthetic expressions, but also tools for reorganizing territory and identity.

Security has also reshaped diplomatic architecture. Following attacks in the 1980s and 1990s, the United States adopted strict withdrawal and blast standards, giving rise to a recognizable type of embassy complex. The Standard Embassy Design program prioritized fortified perimeters, controlled access, and simplified forms, often conflicting with urban continuity. The embassy became a geopolitical lesson in how threat models shape architecture.

The evolution of geopolitical architecture throughout the ages

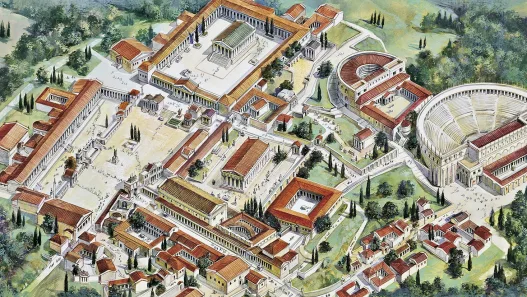

During the imperial and colonial periods, boulevards, railways, and administrative districts were used to integrate regions and demonstrate sovereignty. The modernist era, however, viewed the capital as a laboratory for national identity, and planned cities such as Brasília and Islamabad provided order, efficiency, and unity among different population groups. These landscapes were as much tools for the consolidation of the state as they were blueprints for life.

The post-Cold War era shifted the focus to global networks and security. As cities competed as financial command centers, cultural franchises such as the Louvre Abu Dhabi spread soft power through licensed museums that linked architecture with diplomacy. In parallel, embassy and critical infrastructure designs adopted counterterrorism logic, giving rise to fortified campuses and recessed landscapes that embodied geopolitical risk.

Infrastructure geopolitics is on the rise today. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is exporting ports, railways, energy, and industrial parks on a record scale, leaving a spatial imprint in terms of debt, influence, and connectivity. Meanwhile, since the early 2000s, border walls and fences have proliferated, reshaping ecology and migration routes while also expressing exclusionary policies. These trends remind architects that the most important forms may not be singular symbols, but rather corridors, checkpoints, pipelines, and concessions.

The origins of geopolitics in architectural discourse

Geopolitics entered architectural debates when planners realized that urban order could secure political order. Haussmann’s Paris is emblematic of this: a rebuilt street network that facilitated the movements of the army and police while reorganizing class geographies. Later, colonial capitals replicated this logic through cantons, civil lines, and segregated grids. Reading these plans alongside Scott’s argument about the legibility of the state clarifies how design can make the population administratively visible.

A second origin lies in conflict environments. Eyal Weizman documents that the walls, side roads, and settlements in the West Bank constitute a dynamic control mechanism in which alignment, height, and access are constantly being readjusted. In this narrative, architecture does not merely reflect geopolitics; it produces it and adjusts the realities on the ground through phased operations.

Important theorists and their influence on spatial thinking

Mackinder’s Heartland model and German Geopolitics, later associated with Karl Haushofer, shaped strategic visions reflected in site selection and regional planning. Although they lost credibility when used to legitimize expansionist policies, these theories explain why logistical corridors, canals, and inland capitals have long held political significance.

Lefebvre and Foucault redirected design culture toward power in the everyday living space. The idea that space is socially produced and that orders discipline bodies helps architects view schools, hospitals, prisons, and housing not as neutral containers but as political tools. Sassen and Easterling’s work, meanwhile, updates the framework of globalization, showing how regions and territories adapt to the flow of capital, data, and standards.

Architecture as materialized political power

Monumentality continues to serve as a reliable scenario for authority. The massive axes Speer designed for the rally grounds in Berlin and Nuremberg aimed to naturalize hierarchy through their overwhelming scale. Stalinist complexes and later Soviet public buildings also served a similar function of spectacle and mass appeal. These are concrete examples of propaganda architecture.

Democratic states have used the symbolic form in different ways. While the Open Hand in Chandigarh was designed to symbolize mutual sacrifice, the Three Powers Plaza in Brasília represents the three branches of government in constitutional balance. However, even here, critics point out that planned abstraction can distance power from everyday life and reveal the tension between symbolism and social reality.

The evolution of geopolitical architecture throughout the ages

From empire to nation-state and global network, each era leaves behind its own unique spatial language. Following the increased security measures after 1983 and 1998, “fortress embassy” complexes emerged, featuring deep recesses, non-reflective sightlines, and blast-resistant cladding. After 2001, this language became even harsher and often began to clash with the urban fabric and public diplomacy. More recently, cultural and infrastructural soft power has expanded from branded museums trading in intergovernmental agreements to transcontinental railways and ports that combine foreign policy with construction contracts. Border fortifications have also proliferated in parallel, reshaping ecosystems and human movements on a continental scale.

Case Study: A Masterpiece at the Intersection of Power

Reason for selection and geographical location

The Reichstag in Berlin is a prime example of architecture, history, and state power converging in one place. Located on Platz der Republik beside the Spree River, a short walk from the Brandenburg Gate, this building forms the center of Germany’s parliamentary district and represents the country’s political life since reunification. Its accessible roof terrace and dome make the seat of government both visible and open to the public, a rare feature for a legislative body of this scale.

The building is located within a planned complex known as the “Federal Ribbon,” which spans the Spree River and symbolically unites the former East and West. This complex consists of the chancellery and parliament buildings. This linear structure, which also includes the Paul Löbe House and the Marie Elisabeth Lüders House, was designed to spatially connect the executive and legislative powers on both sides of the river bend known as the Spreebogen after reunification.

The political and cultural forces behind the commission

Following reunification, the Federal Parliament decided on June 20, 1991, to move the seat of government from Bonn to Berlin. This decision, which paved the way for the establishment of a new parliamentary complex in the historic capital, was adopted after a contentious vote. The 1994 Berlin-Bonn Act implemented this decision and confirmed that the Reichstag, once rebuilt, would become the permanent seat of the Federal Parliament.

In the early 1990s, following an international competition, Foster and Partners were selected to rebuild the war-damaged and altered building as an open, accessible, and energy-efficient parliament building. The stated design brief brought together four priorities that still define the project today: a functional democratic forum, a clear reading of history, public access from street to roof, and a strong environmental agenda.

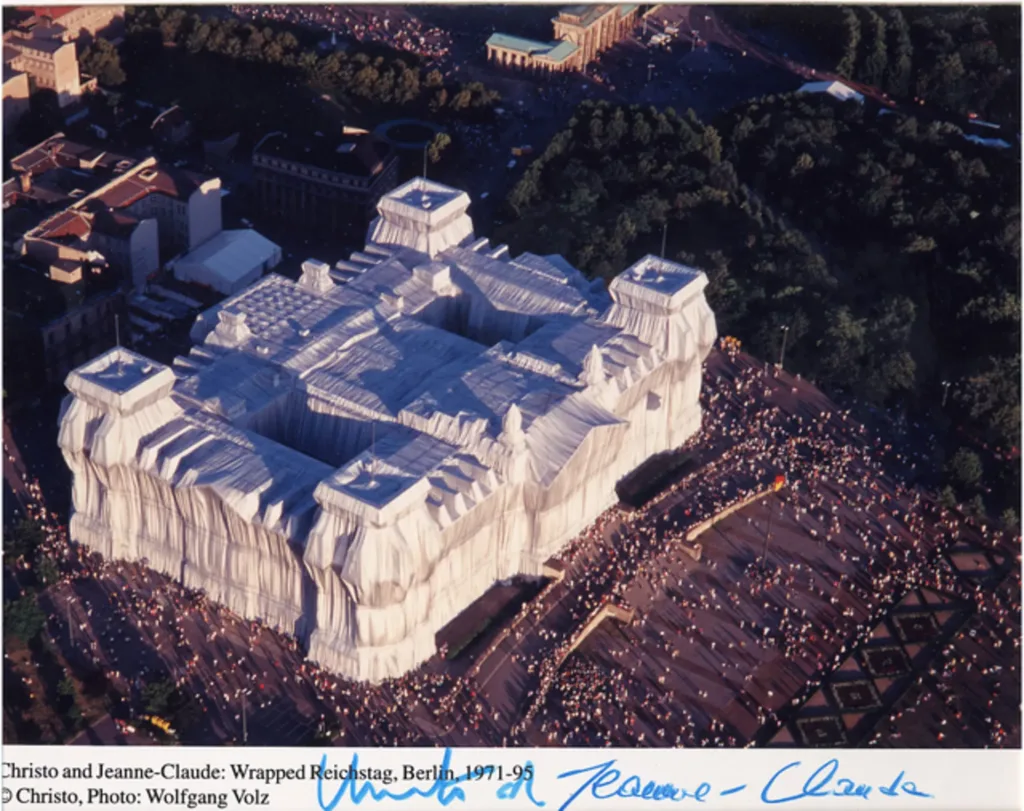

Before its reopening, Christo and Jeanne Claude’s 1995 work Wrapped Reichstag transformed the building into a temporary work of art, reshaping the public image of reunified Germany and drawing international attention to the site. Completed with 100,000 square meters of silver fabric and a large installation team, the project became a cultural turning point and rekindled public curiosity about the building’s future role.

Symbolism in its form and arrangement

The glass dome with twin spiral ramps above the general assembly hall carries an open symbolic meaning. Visitors literally climb above the hall and look down onto the debate floor. This staged inversion implies that political control is in the hands of the people. The dome also serves as a source of daylight for the hall, combining architectural flair with functional performance.

The mirrored light cone and controlled oculus manage glare and glare effects, while the Bundestag campus uses combined heat and power with biofuel to reduce emissions at the regional level. These systems link democratic transparency with environmental responsibility, embedding the energy story into a national monument.

Inside, the layers of history remain legible. Foster’s team preserved graffiti from selected Soviet soldiers dating back to 1945 and other material traces uncovered during reconstruction, transforming the corridors and walls into a deliberate archive of conflict and recovery. This curatorial approach incorporates memories into daily parliamentary life.

Accepted and controversial meanings over time

The project quickly became a symbol of contemporary Berlin. The parliament building, which was opened to the public by offering free registration in advance for its dome and roof terrace, became one of the city’s most visited sites and gave architectural form to the government’s principle of transparency.

Critics also interpreted the dome’s transparency as a powerful but risky metaphor. While some academics argue that architecture alone cannot guarantee an open political system, others see the dome as a successful civil theater that reshapes a building associated with dictatorship and division. These debates keep the project intellectually vibrant.

Spatial Strategies and Design Responses

Site planning with regard to boundaries and edge conditions

Reading the border as a design summary. Borders are not lines; they are thickened areas where law, surveillance, living space, and memory overlap. For example, on Germany’s internal border, the Wall’s layered “death strip” combined lighting, towers, patrol roads, and ditches to transform a political claim into a spatial system, reminding designers that a “border” could extend several hundred meters deep.

Encounters, barriers, and the civilian camouflage of security. Following the 1998 embassy bombings, US facilities adopted generous barriers, crash-resistant landscaping, and reinforced perimeters. The U.S. Embassy in London transformed these into public amenities: the crescent-shaped water feature, retaining walls, and fences provide the necessary blast barriers while appearing more like a park than a fortress. High-performance glass and ETFE membrane regulate light and visibility, keeping the facility open while meeting stringent security criteria.

Negotiated borders and cross-border frictions. Modern ports and stations often push the border further north. French-British “side-by-side controls” place British officials in French terminals, while US pre-control creates sterile security lounges in foreign airports. The architecture here choreographically arranges the transfer of jurisdiction, sterile corridors, and sovereign rooms that are within but separate from the host city.

Ecological boundaries as a design responsibility. Where boundaries are defined by fences or walls, land planning takes on a biopolitical character. Research shows that wildlife mobility has significantly decreased at the solid barriers along the US-Mexico border and that fragmentation has increased at the new fences in Europe. Landscapes, culverts, and passages are no longer opportunities but elements that mitigate the effects of geopolitical boundaries that interrupt migration and gene flow.

Circulation, access, and control in the geopolitical sphere

From the promenade to the checkpoint. Circulation is a constitutional issue where the area is contentious. Eyal Weizman’s statements on Israeli checkpoints, elevated roads, and underground tunnels demonstrate how vertical movement layers distribute rights, visibility, and delays, transforming daily routes into tools of governance.

Protocols included in the plans. In diplomatic facilities, public, consular, and security flows are separated well before the gate. Guidance drawn from US security criteria and embassy program history subsequently formed the standoff, blast geometry, and access zone coding developed under “Design Excellence,” compelling architects to integrate control without succumbing to bunker typologies. At Nine Elms, these flows are legible through split lobbies, security forests, and a spiral public path that never compromises the secure core.

CPTED and defensible space as civil rhetoric. Natural surveillance, neighborhood empowerment, and controlled access are now part of the common language of urban design. These ideas, born from Oscar Newman’s concept of defensible space and matured through CPTED applications, have been carried over from residences to embassies, parliaments, and transportation hubs. In these spaces, sightlines, edges, and thresholds quietly fulfill their functions long before visible barriers appear.

Front strategies as diplomatic or propagandistic gestures

Transparency, carefully qualified. Facades often reflect the image a regime chooses to project. In London, the embassy’s crystal cladding and ETFE sunshade conceal laminated blast-resistant glass and deep structural reinforcement while bringing the rhetoric of clarity and sustainability to the fore. While the message reads as openness, the cross-section reveals a different control plan.

Universalism as a brand. Jean Nouvel’s design for the Louvre Abu Dhabi transforms the perforated dome into a “rain of light,” turning a geopolitical project into a branding tool. The museum continues to exist thanks to a 30-year intergovernmental agreement that licenses the Louvre name and expertise. This cultural diplomacy agreement, embodied by a floating canopy visible from the sea and the shore, not only provides shade for the galleries but also frames a national narrative of bridge-building. The facade not only provides shade for the galleries but also frames a national narrative of bridge-building.

Glass as public ethics. Continental parliaments and headquarters often use large glass walls to symbolize accessibility and accountability. When read alongside more defensive state architectures, these transparent facades are part of a long tradition of using visibility as political theater, relying on the layered security behind the curtain wall to establish legitimacy through exposure.

Landscapes and scenery as a geopolitical framework

Axes that shape the nation. Capitals use a long-term perspective to harmonize institutions and memory. The Washington Mall, expanded by the 1901 McMillan Plan, creates a democratic promenade between the Capitol and the Potomac. Paris’s Axe historique unites the palace, square, obelisk, arch, and Grande Arche into a single line of power encompassing successive regimes. These are not neutral landscapes, but spatial constitutions.

The imperial capital became urbanized. Beijing’s north-south Central Axis connects palaces, ceremonial gates, and public spaces into a regulatory backbone recently inscribed on the World Heritage List. The axis encodes a cosmology of order and hierarchy; the palaces, colors, and rooflines of the Forbidden City reinforce political centralism through architecture.

Observing the enemy. In the Korean DMZ, observation towers and the blue conference booths of the Joint Security Area enable controlled observation of the other side of the border. The platforms, sightlines, and camera positions fix the image of the border, which is both a tourist attraction and a diplomatic stage, proving that even a landscape can be controlled.

Reframing inherited axes. New Delhi’s Central Vista redevelopment project and the renaming of Rajpath as Kartavya Path enable the rewriting of a boulevard from the colonial era for a post-colonial state. The design renews green spaces, promenades, and institutions while also recoding the boulevard’s meaning in the national lexicon. The landscape becomes a tool for rewriting political time.

Borders as memorial sites. In Belfast, “peace lines” transform ordinary streets into permanent interfaces. Murals, doors, and timed openings turn the ceasefire into urban furniture, and the wall itself becomes an interpretive landscape of division and temporary reconciliation.

Importance in the Geopolitical Context, Technology, and Sustainability

Material selection and supply chain dominance

Critical minerals are shaping the summary. Design decisions are now dependent on a small group of mining inputs concentrated in a few countries. China’s permit controls on gallium and germanium since August 2023 and new permit rules on certain graphite grades since December 2023 have demonstrated how quickly access to semiconductors, batteries, and clean energy hardware can be restricted. As a result, architects specifying photovoltaics, EV infrastructure, or high-performance glass are influencing not only product catalogs but also geopolitical systems. The European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act responds to this by setting targets for diversifying supply, expanding processing and recycling in Europe, and reducing strategic dependencies by 2030. The International Energy Agency’s latest outlook follows these markets and warns that resilience depends on diversified projects and greater transparency.

Policy tools shape the materials list. Industrial policy now acts as a materials determinant. The US CHIPS and Science Act subsidizes domestic semiconductor production, while the Inflation Reduction Act’s Domestic Content Bonus rewards projects that use US steel, iron, and manufactured goods. Public procurement seeks to reduce embodied carbon through the Buy Clean guide, which prioritizes low-carbon concrete, steel, asphalt, and flat glass. On the trade side, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is gradually implementing the reporting and subsequent charging of emissions contained in imported cement, steel, aluminum, and other products, creating price signals that feed back into supply chains and design choices.

Traceability is becoming a design criterion. Customers and regulators are increasingly questioning where materials come from and under what conditions they are produced. The IEA’s work on mineral traceability and critical mineral security for 2025 highlights oversight chain tools, audits, and data platforms that verify origin, processing routes, and ESG claims. For construction products, Environmental Product Declarations compliant with Buy Clean programs make specific emissions readable for specification setters and contractors. When these tools come together, origin and carbon, color, or strength class become selectable attributes.

Technological systems and infrastructure dependencies

Data travels across vulnerable sea routes. Over 95% of international data is carried via undersea fiber optic cables. Cable cuts in the Red Sea in 2024 and 2025 disrupted connections from Asia to Europe and reminded designers that cloud services, smart buildings, and digital twins are all tied to a fragile, repair-dependent network. Campus planning for mission-critical facilities now considers various cable connections, multiple provider routes, and offline modes for security systems.

Network sovereignty drives supplier and cloud choices. The UK’s order to remove Huawei equipment from 5G public networks by the end of 2027 is an example of how security policy impacts technology choices and renewal programs. In the EU, the new Data Act strengthens portability rights between cloud providers and aims to prevent lock-in, while the Gaia-X program promotes unified cloud standards to keep data control closer to European laws. These steps influence where data centers are located, how contracts are written, and how public customers define compliant digital infrastructure.

Electricity and water connect technology to the region. The IEA forecasts that data center electricity demand will nearly double by 2030, reaching 945 TWh. The primary reason for this increase is artificial intelligence. Operators and cities are grappling with the water footprints of different cooling systems, grid capacity, on-site production, and heat recovery. At the same time, as the 2022 Nord Stream sabotage demonstrated, energy pipelines and interconnections have become geopolitical targets. Therefore, redundancy and local storage are becoming fundamental planning assumptions for energy-intensive campuses.

Resource efficiency as a soft power tool

Standards as diplomacy. Global rating systems provide a common language for signaling environmental leadership to states and cities. LEED currently has over 195,000 certified projects in 186 countries and regions, while BREEAM continues to grow in new asset classes such as data centers and cold storage facilities. These labels are not just scorecards; they are visible commitments that appear in investor presentations, cultural offerings, and embassy briefing notes.

Flagship buildings that deliver performance and make a compelling statement. The U.S. Embassy in London combines stringent security measures with a public landscape and energy narrative featuring high-performance glass behind ETFE membrane, daylight control, CHP, and water reuse. The building serves as a diplomatic message blending openness, resilience, and carbon consciousness, setting an example that many governments are adopting for consulates, museums, and parliaments.

Trade policy strengthens the concept of efficiency. Europe’s CBAM links market access to carbon intensity, forcing cement and steel suppliers to document and reduce their emissions, or else face a border charge. As reporting phases and fees come into effect, project teams will be able to source and justify low-carbon materials more easily, making the policy a competitive advantage for efficient design.

Climate resilience in uncertain political environments

From risk awareness to adaptation planning. The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report highlights increasing temperatures, floods, and compound risks for cities and infrastructure. ISO 14090 provides a management framework for integrating adaptation into strategy, procurement, and operations, meaning that resilience can be defined and monitored with the same rigor as safety or energy.

Insurance markets are rewriting feasibility. As disaster losses increase, insurance companies are withdrawing from high-risk areas or raising premiums, changing the economics of housing, coastal projects, and critical facilities. Recent reports and decisions in the United States show that major insurance companies are reducing coverage in wildfire and hurricane zones, and that site selection based on risk information, flood-proof ground floors, and robust fire design have become integral to financial sustainability.

Policy frameworks to enhance resilience. The EU Resilience Strategy calls for smarter data, faster action, and more systematic measures, nature-based solutions, and resilience standards integrated across all sectors. For designers, this means shaded public spaces, blue-green streets, backup energy and water sources, and evacuation-priority circulation plans that can withstand outages lasting several days. The goal is simple and strategic: to keep communities functioning when politics and weather are unstable.

Results for Current Applications and Future Trends

Courses for architects working in conflict zones

Address the issue of protection not as an add-on, but as a design program. In areas affected by conflict, the obligation to protect cultural property is clearly stated in law. The 1954 Hague Convention and its protocols define obligations and symbols such as the Blue Shield emblem, which identifies protected areas and personnel. Reading these documents at the beginning of the briefing helps teams incorporate protection measures into site selection, phasing, and documentation processes, rather than adding them after damage has occurred.

Plan with recovery frameworks that will remain valid after the crisis. The urban recovery guide by the UN-Habitat and ICOMOS-ICCROM community demonstrates how emergency stabilization, medium-term reconstruction, and long-term social rehabilitation are interconnected. Designers use these frameworks to align temporary works, governance, and supply not only with rapid reconstruction but also with sustainable civil life.

Coordination with humanitarian protection practices. In volatile environments, architectural decisions intersect with protection efforts carried out by humanitarian actors. The ICRC’s Professional Standards for Protection Work and its research on urban warfare highlight risk mapping, harm prevention analysis, and the realities of intense urban conflict. Built environment strategies that respect these practices reduce unintended consequences and support all parties’ compliance with the law.

Ethics and accountability in geopolitical commissions

Base decisions on clear professional standards. Professional standards make the public interest functional. The AIA Code of Ethics and the RIBA Code of Professional Conduct establish the principles of public interest, integrity, and environmental responsibility that apply regardless of the project’s location or client type. Referencing these rules in fee proposals, risk registers, and design briefs translates values into contractually enforceable commitments.

Respect human rights. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights now form the basis of corporate behavior. For architects, this means examining clients and construction sites for human rights risks, communicating with affected communities, and identifying clear solutions. Consider the three core elements of the UN Guiding Principles as a checklist for project management.

Understand sanctions and cross-border risks. Since 2022, many firms have suspended or withdrawn from projects in sanctioned jurisdictions and adopted internal controls for service prohibitions. Current US and UK guidance demonstrates how architecture and engineering services can fall under sanctions regimes, including through indirect provisions. Here, the concept of ethics is not abstract. It is about compliance, record-keeping, and willingness to refuse work.

Architectural diplomacy and soft power strategies

Use buildings to reflect values, not slogans. Joseph Nye’s definition of soft power emphasizes attractiveness and credibility. Cultural institutions, embassies, and public buildings can embody these characteristics when program, access, and performance are aligned. Independent metrics such as the Global Soft Power Index show how perceptions of culture and governance shape impact. Therefore, architecture linked to genuine openness and environmental performance is important.

Use cultural agreements as urban tools. Louvre Abu Dhabi is a highly notable example of a coastal area being repositioned through an intergovernmental agreement that created a museum, a brand license, and an exchange of expertise. The extension of the agreement until 2047 highlights the long-term goals and urban impacts of cultural diplomacy.

Support narratives with reliable programs. Cultural networks such as the British Council and Goethe-Institut match buildings with funding, residency, and skills programs. Research and grant programs frame heritage preservation and cultural exchange as relationship building rather than messaging, which tends to produce more resilient soft power outcomes than iconic forms.

Emerging paradigms: networked states, digital borders, and architecture

Networked communities are called semi-civil structures. The idea of a “network state” envisions highly compatible online communities that finance their regions through crowdfunding and seek recognition. Whether or not this idea achieves statehood, it highlights an existing design problem: spatializing digitally coordinated communities with their own governance rituals, privacy expectations, and capital flows.

Borders are becoming biometric and data-driven. The EU’s Entry/Exit System will become operational on October 12, 2025, and will be implemented in phases until April 2026. With this system, biometric records will replace passport stamps at airports, ports, and train terminals. This is causing architectural attention to shift to flows, kiosk layouts, and accessible queue systems that can manage increased traffic without compromising privacy and rights from the design stage.

Digital sovereignty is reshaping infrastructure choices. Data localization rules, geo-blocking policies, and cloud switching rights are drawing new boundaries in the code. Architects planning data-intensive campuses must now consider where data can be stored, how it can be transported, and what happens when proprietary platform services are restricted. The Starlink example and the fragility of undersea cables underscore why redundancy, diverse routes, and elegant failure modes must feature in master plans.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.