The origins of architectural reality

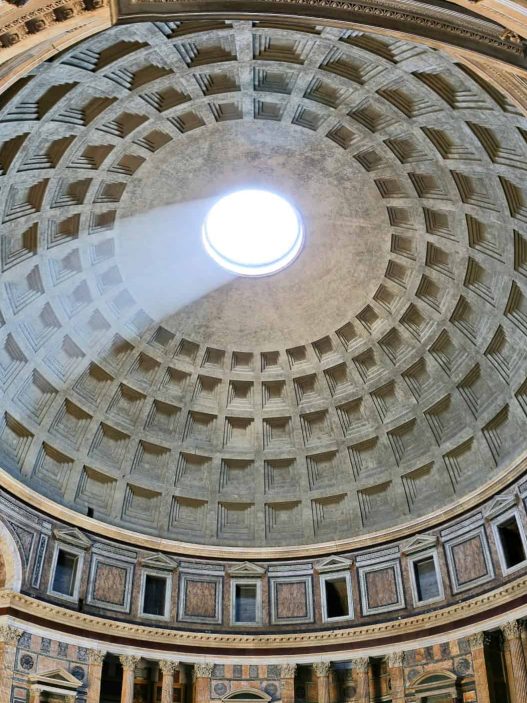

Architectural “integrity” begins with a simple idea: A building must be meaningful in its structure, use, and appearance—Vitruvius’s classical triad of strength, functionality, and beauty. When these three elements are in harmony, we feel a sense of authenticity: the parts we touch, see, and move through feel as if they are in harmony with the building’s structure and purpose.

Over time, “material fidelity” has become a practical rule: Use each material where it works best and don’t hide its characteristics. Concrete can retain its wood grain, bricks should look like bricks, wood should look like wood, not like a imitation printed on another surface. This principle was of central importance to early modern thought and still determines many contemporary details today.

Dorian Renard is blowing plastic like glass in order to re-evaluate its value.

Integrity, structure, and services become visible in high-tech architecture that captures the public’s attention. At the Centre Pompidou in Paris, pipes, cables, and escalators have been moved outside so that visitors can understand how the building works. At the Lloyd’s Building in London, elevators and supply lines have been placed on the facade to clearly organize the interior space. These are design decisions that make the systems understandable.

Philosophical roots: From Vitruvius to Ruskin

Vitruvius provided Western architecture with an ethical compass: to build well (stability), to serve people (utility), and to inspire them (aesthetic pleasure). Centuries later, translators like Henry Wotton popularized this triad, and it still shapes discussions about “truth” in design—especially when one value is pursued at the expense of the others.

John Ruskin sharpened moral acuity with “The Lamp of Truth” and argued that illusions, false surfaces, or apparent structures were a kind of deception. He even cataloged deceptions—structural, superficial, and functional—and demanded that architects make structure and craftsmanship visible. Luxury is not necessary to be good, he said, but honesty is.

Other theorists further complicated this picture. Eugène Viollet-le-Duc praised forms that expressed the logic of a material—an early form of structural rationalism—while Gottfried Semper proposed the “dressing” (Bekleidung) of architecture and saw cladding as a narrative linked to textiles. Together, they argue that honesty is not only about revealing, but also about expressing the true idea of a structure—how the layers function, what is load-bearing, and what is not.

Distinguishing originality from literalism

Originality does not mean tearing buildings down to their foundations or turning every pipe into a performance piece. Sometimes “honest” architecture is silent: a brick cladding that is clearly recognizable as cladding (and does not claim to bear loads) or a rain protection cladding that is clearly recognizable as a layer. Problems arise when surfaces take on a role they don’t possess—for example, artificial stone that is supposed to look solid—or when a facade is protected without any meaningful relationship to what lies behind it (a highly controversial practice known as facadism).

Venturi and Scott Brown’s famous “duck and gilded cage” example provides a practical test. The “duck” is literally a symbol—the building has taken the shape of what it sells. The “gilded cage” is a simple box that communicates through signs or surface markings. Their aim was not to show that one of these is always correct, but to demonstrate how buildings convey meaning and to warn against confusing theatrical form with clear function. In other words, a building can “lie” as much through excessive concealment as through excessive literalism.

Design application: Decide what to show clearly, what to hide, and—very importantly—how you want to convey the truth at every level. If you show structures or services clearly (Pompidou, Lloyd’s), do so to improve readability and usability, not as a gimmick. If you hide something, make it clear that it is hidden. When adapting cultural heritage, present the old and the new as compatible partners, not as irrelevant background elements. These are small, instructive acts of honesty that people can understand without a textbook.

Materials and the illusion of reality

Counterfeiting and Authenticity: Deception, Imitation, and Simulacrum

In buildings, facade cladding is a thin, non-load-bearing layer that matches the appearance of the material it covers – thin stone, brick, laminate. When used as cladding and not as a structural element, it can be completely authentic. For example, natural thin stone cladding panels are typically approximately ½ to 1 inch thick and weigh 7 to 15 lb/ft² – they are lighter and easier to install than full-thickness stone, which has an impact on both cost and load paths.

Imitations – such as wood-veined laminates or wood-look aluminum – solve real problems: cost, maintenance, hygiene, fire hazard. Formica’s long history of printed patterns shows how simulated appearances have been adopted for the longevity and ease of cleaning of interiors. Today, manufacturers offer wood-look printed metal cladding to create low-maintenance outdoor spaces. The look is “wood,” the behavior is “metal.” If the drawings, features, and details clearly show this, it is not a lie, but a choice.

Philosopher Jean Baudrillard defined certain copies as simulacra – representations that break away from the original and become their own reality. In the built environment, this could be, for example, a shopping street that looks “historic” but is entirely new, or a composite material marketed as “authentic” stone. The ethical question shifts from “Is this real?” to “What is this saying, and is this story clear?”

The ethics of material representation

The facade is not a structure, but a rain screen: a protective cladding against outdoor weather conditions, a ventilated cavity, and a watertight inner layer. Details that make these layers distinct (visible fasteners, shadow joints, section drawings) give the building a realistic impression of its functionality. Confusion arises when a cladding is marketed as solid.

“Physical reality” also relates to performance under harsh conditions such as water, fire, and heat. Traditional exterior insulation and finish systems (EIFS) installed as non-vented coatings trapped water and caused rot; modern vented EIFS and ventilated coatings aim to eliminate this problem. In areas with a high risk of forest fires, where safety is the top priority, regulations and best practice guidelines favor non-combustible or flame-retardant coatings (metal, fiber cement, plaster) over combustible alternatives.

A material may appear environmentally friendly but still have a high carbon footprint. Therefore, designers are demanding Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), which are ISO-based reports verified by third parties that reveal the impacts of the life cycle (e.g., greenhouse potential). Choosing the “more genuine” product means evaluating not only the surface but also both its appearance and tangible effects.

Simply preserving the historic facade while renovating everything behind it may enhance the street view, but it can distort the historical reality. Monument preservation groups are increasingly warning that projects where only the facade is preserved risk turning architecture into mere decoration, especially when old and new elements do not clearly integrate with each other. The same principle applies to materials: superficial nostalgia should not be allowed to distort a building’s true essence.

Case studies on material fraud

The Grenfell investigation revealed that aluminum composite panels (ACM) with a polyethylene core, which are flammable in high-rise buildings and could lead to disaster, were used on the refurbished facade. In addition, there were other failures on the part of industry and regulatory authorities. This was more than a technical error; it was a failure in terms of accurate performance declarations, supply, and oversight. Appearance took precedence over functionality, leading to fatal consequences.

In the 1990s and 2000s, many EIFS facades were installed as watertight systems without drainage pathways. When rainwater seeped in due to hairline cracks or deterioration of the waterproofing compound, the structures could not dry out, leading to moisture damage. The lesson to be learned: A coating that appears tight is only truly tight when it accounts for and addresses the inevitable leaks. Drainage and ventilation systems for EIFS were developed as a corrective measure.

Wood-patterned metal cladding, drawings, technical specifications, and labels clearly indicate this, and if it is preferred for durability or resistance to forest fires, it can be considered acceptable. In WUI areas, authorities and research groups recommend non-combustible or flame-resistant facades; in this case, “artificial wood” may be a safer choice. The key point is information: The public should know that it is metal and not assume it is solid wood.

The importance of form, function, and performance

If the form follows the deception

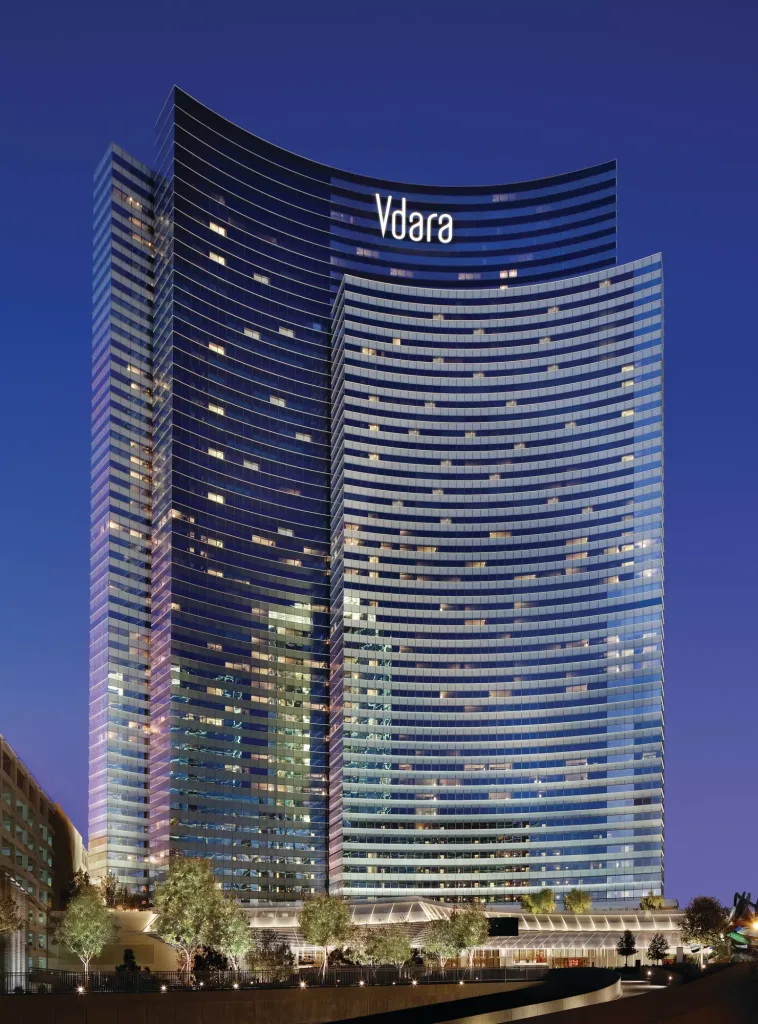

An eye-catching design can be misleading if it creates the opposite effect of what it promises. For example, concave glass facades can concentrate sunlight into dangerous “hot beams.” The 20 Fenchurch Street building in London – nicknamed the “Walkie-Talkie” – is known to have scorched the street below and even melted a car’s hood because its facade acted like a giant mirror. The solution involved temporary shields and long-term measures – an expensive lesson reminding us that visual effects cannot replace solar analysis.

The Vdara Hotel in Las Vegas also experienced the same problem: a curved, reflective coating concentrated intense heat onto the pool terrace. Guests complained of burns and melted plastic; the construction company later described this as the “sunlight convergence” phenomenon. The lesson here is simple: If the shape increases risks (glare, wind, heat), it is essential to redesign or modify the facade in a way that works well for neighbors and users—not just to look good in designs.

Even popular icons have learned this. At the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, polished stainless steel panels caused dazzling reflections and temperatures of around 60 °C on the pavement. The practical solution was to convert certain panels to a matte finish. This restored comfort without compromising the architecture. Performance is part of the reality: If a beautiful surface negatively impacts public life, the ethical response is to change the surface.

Hidden features: Mechanical floors, false walls

Tall buildings conceal many technologies—sometimes for good reasons, sometimes to manipulate perception. In New York, construction companies used “mechanical voids” (very tall service floors not included in gross floor area) to build loft apartments higher and increase apparent height. The city responded in 2019 by limiting the permitted height of mechanical voids in residential high-rises. Here, politics intervened to make the skyline more honest again: Height should stem from the actual program and not from voids hidden as systems.

Other “hidden” measures are actually clearly revealed when reading the section. Super-slim towers like 432 Park Avenue feature open, double-height machine/wind floors across all twelve stories to allow air to pass through, which interrupts vortex shedding and reduces turbulence; complementary damping measures handle the rest. These voids appear as empty strips on the facade, but they are an expression of structural integrity – making comfort and safety visible to those who know what to look for.

Not all false walls are deceptive. Double facades and rear-ventilated rain protection facades create voids that drain water, reduce noise, and provide natural ventilation through wind pressure and the chimney effect. These are “masks” that serve a purpose, and the ethics lie in the details and transparency: Make the layers recognizable as layers and explain their role in drawings and technical specifications. A calm facade can still convey how it provides comfort and dryness to its occupants.

Symbolism in design language and honesty in the literal sense

Venturi and Scott Brown’s “Duck and Decorated Shack” model remains an effective tool for deciphering meanings. The “Duck” is a symbolic structure (form conveys the message); the “Decorated Shack” is a simple structure that communicates through signs or surfaces. Their aim was not to ban one or the other, but to draw our attention to how architecture speaks and to prevent theatrical form from being confused with functional clarity.

Semper’s concept of “clothing” adds another dimension: Clothing is not untrue when understood as a textile product of cultural and technical significance, a covering with its own logic. Understood in this way, the symbol and the surface can be honest when they accept what they are: a communicative layer on a working body. When the surface claims to have a structure or history it does not possess, ethical boundaries are crossed.

The architect’s role: Storyteller or herald of truth?

Intentional illusions in architectural narratives

Architecture has always drawn inspiration from theater: consider the baroque tricks like Borromini’s corridor in Palazzo Spada, where forced perspective is applied; here, a short gallery appears long and majestic. This artistic trick is deliberately chosen, easily explained, and rather than concealing the structure or security, it is part of a cultural language that inspires awe. In other words, this is not a lie to conceal the performance, but rather a narrative embellishment that frames the experience.

Contemporary discourse often legitimizes “storytelling” through atmosphere and sensory experiences: Peter Zumthor discusses the design of atmospheres, while Juhani Pallasmaa argues against a vision-centric culture, advocating for the inclusion of touch, sound, and warmth in design intent. Here, storytelling is not about deepening reality or distracting attention from it – the story is an opportunity to talk about what residents actually feel.

The ethical breaking point is presentation. Hyperrealistic visualizations can “sell” a version of social life, sunlight, or vegetation that may never be real. In scientific and technical commentary, clearer standards have been demanded so that visualizations support informed decisions rather than manipulating approvals. As a general rule, clearly state assumptions (season, time of day, lens), avoid fabricated contexts, and separate art from evidence.

The architect’s moral compass: Who decides what is honest?

Professional conduct rules require transparency and prohibit misrepresentation. The AIA Code of Ethics requires honesty in public communications and communications with clients (e.g., Rule 3.301) and prohibits providing misleading information about qualifications or achievements (Rule 4.201). Sample rules (NCARB) and relevant UK regulations (RIBA; ARB Architects Code) also establish honesty and accuracy as fundamental obligations. These are enforceable standards – disciplinary action is taken if members make false statements about their qualifications or achievements.

Integrity extends to the behavior of buildings. Following the Grenfell incident, the UK Building Safety Act 2022 clarified the roles of responsible parties (planners, contractors) and strengthened accountability to residents. The government publishes progress reports on the investigation’s recommendations. In practice, decision-making authority is shifting towards a model based on regulation and public scrutiny: Architects must be able to justify safety decisions and not merely state their intentions.

Beyond security, originality is a shared value negotiated with communities. The Nara Document (1994) expanded the concept of authenticity to include cultural context and intangible values, reminding designers that the concept of “reality” is not only a material representation but also the true meaning of a place. This perspective encourages architects to create new works that are consistent with historical narratives, while ensuring that facades are not transformed into stage sets.

Public expectation and professional justification

Citizens expect accurate information, safe buildings, and a voice in the process. In many English jurisdictions, public hearings and community involvement statements are required for major applications. Authorities publish hearing dates so citizens can respond. These procedures formalize the expectation that graphics, reports, and claims must be accurate enough for non-experts to evaluate.

A professional justification is not merely a statement of intent, but also evidence. Ethical rules require architects to avoid misleading statements and to clearly state their interests in their public statements. In connection with safety regulations (e.g., Building Safety Act officials), this situation creates a two-key system: a convincing story + verifiable performance. If the measured values (fire safety, energy, wind, glare) contradict the rendering, the professional task is to change the design, not the story.

Practical steps help align the narrative with reality:

- Mark the image as a hypothesis, not reality, and specify the assumptions (date, weather, plant maturity). Research shows that prior visualizations can influence decisions; transparency reduces this effect.

- Publish the performance rationale alongside the concept: for example, why a double-shell facade, the results of wind studies, how the materials meet the fire protection strategy. Research conducted after the Grenfell fire and the three-month advisory reports raised public awareness about the difference between appearance and behavior.

- Involve them early and in good faith. There are frameworks for involving the community to identify disagreements before the design is finalized. Use these as input for the design, not as obstacles.

An architect can be a storyteller and also a truth-teller—provided the story is based on verifiable achievements, clear authorship/attribution, and genuine public dialogue. Professional codes establish minimum standards; laws concerning public trust and safety set the boundaries.

Notable examples of architectural deception

The hidden glass house: Transparency and privacy

Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House and Philip Johnson’s Glass House elevated transparency to a virtue: Walls disappear, the landscape flows through, and the structure emerges. However, life inside is not always serene. Critics (and the client himself) described the Farnsworth House as beautiful but frustrating to live in – transparent by day, exposed by night. Openness, privacy, glare, and comfort can become a spectacle if not consciously resolved.

Johnson’s glass house was designed as a viewing pavilion and landscaped – “invisible from the road” – and combined with the nearby brick shelter to form a refuge. The property’s design presents a quiet contradiction: radical transparency for the object, strategic privacy for living. Privacy is not within the glass, but behind the curtain – behind the fences, hills, and a solid annex reopened to the public after restoration.

Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre softens the transition by replacing transparent glass with glass bricks and interior walls, creating a milky veil. What is important is that at night, when interior light dominates, “privacy” is reversed. This reminds designers that the one-way effect stems not from the magic of glass, but from balanced lighting. The house leaves such an intimate impression precisely because it clearly reveals the boundaries of its shell.

Iconic buildings with hidden purposes

Some cities hide chaotic systems behind their elegant facades. Located in Brooklyn Heights, 58 Joralemon Street is a historic “Brownstone” building whose blacked-out windows conceal a ventilation shaft for the New York subway. Located in London’s Bayswater district, 23-24 Leinster Gardens are facade buildings that conceal an open rail pit. This pit was originally necessary for steam extraction – an urban trick used to visually maintain the terrace’s integrity.

If you only preserve the historic facade and completely rebuild the rest, you can maintain the street view, but you also dilute the history. Writers and critics concerned with monument preservation define facadism at best as a pragmatic tool, at worst as a cynical staging. Ethics depend on clarity: Does the new interior treat the facade as a shell, or does it act as if it were reviving the old building?

Is it postmodern acting or a post-truth application?

Michael Graves’ Portland Building—one of the early icons of postmodernism—was leaking and deteriorating. The city renovated its interior while preserving its appearance by covering it with a uniform aluminum rain screen. While admirers labeled this restoration a betrayal, engineers viewed it as long-overdue honesty in terms of performance. This incident raises a difficult question: Is it more appropriate to preserve the appearance, or to finally rebuild the building to make it functional?

At Disney’s headquarters in Burbank, the seven dwarfs are transformed into “caryatids” – a nod that clearly showcases the brand’s myth. This is a fun and eye-catching symbolism, but no one confuses the dwarfs with a structure in a technical sense. This is the “decorated cottage” logic on a billboard scale: The surface speaks, while the systems handle the work in the background.

Johnson and Burgees distinguished themselves from the anonymous glass box by using pink granite and a split “Chippendale” roof facade for AT&T (now 550 Madison). Subsequent proposals to alter the base sparked preservation battles, proving that postmodern symbols, even if not structural, hold public significance. From the Venice Biennale’s “Strada Novissima” facade to today’s redesign debates, postmodernism continually tests the boundary between expression and imitation.

Towards a new transparency ethic in design

Can architecture be both honest and inspiring?

Yes – if beauty stems from what a building actually is and what it needs to do. The work of Lacaton & Vassal exemplifies this: “Never demolish… always redesign,” they say, creating space, light, and thermal comfort by reusing structures rather than removing them. This was presented as a social and ecological ethic in the Pritzker Prize lecture – proof that generosity and restraint can be inspiring at the same time.

If the description says “energy efficient,” show the process from design to usage results. Use methods from the design stage (CIBSE TM54) and adhere to operational assessments (NABERS UK’s “Design for Performance”) so that users and the public can see that the promises are true. This transparency is a design step, such as selecting systems and details that behave as claimed.

Images shape public approval. Ensure that lighting, camera data, and context are not “beautified” by following guidelines for verified views (e.g., the Landscape Institute’s TGN 06/19 guideline). Specify rendering assumptions and display evidence alongside the artwork; this builds trust without compromising the poetry.

Regaining trust through material and spatial integrity

Request Environmental Product Declarations for carbon and Health Product Declarations for content materials. By combining EPDs/WLC assessments (RICS, 2nd edition) with HPDs, discussions shift from image issues to facts, preventing greenwashing.

Following the Grenfell fire, product information must be clear, precise, up-to-date, accessible, and unambiguous – the Construction Product Information Code formalizes this standard. The “red thread” must be maintained at the building level: a digital, complete record from design to use, so that safety decisions can be verified over time.

Read the layers as layers: Rain protection as skin, voids as service/wind floors, and renovation as renovation. Support this with public objectives (RIBA 2030; LETI) so that spatial decisions are not only stylistic but also aligned with CO2 and comfort targets. Publishing figures alongside drawings is an ethical requirement.

Honesty as a design principle in future applications

- Performance-based presentation: Include TM54 results and a DfP plan in each concept package. Commit to conducting a business assessment within two years of the move.

- Product accuracy: Request suppliers to participate in CCPI and provide EPDs/HPDs for key components.

- Prove this in practice: Include Soft Landings/POE in the scope and publish a summary of the results in simple language; transfer the information obtained to the next task.

- Image ethics: Use validated imaging methods (camera metadata, measurement control) and specify all imaging assumptions.

- Public disclosure: To the extent permitted by guidelines, information regarding energy and water consumption must be disclosed to the public annually (NYC LL84 is an example of city-level transparency).

Adopt the “Retrofit First” strategy and provide your customers with a multi-year plan that gives them honest information about the steps, costs, and benefits. The EU’s new directive on building energy efficiency formalizes renovation passports, which are structured roadmaps that reduce risks and help implement decisions. Link your roadmap to CO2 balancing throughout the entire life cycle to ensure design intent, phased planning, and impacts remain aligned.

Transparency is not a burden, it is a design language. When the public can understand what a building is made of, how it works, and why certain decisions were made, trust returns, and with it, enthusiasm. Aim for projects that are easily readable: be generous with key points, meticulous with data, measured in your statements, and transparent in your compromises. This is charismatic honesty.