Architecture is a site of constant negotiation between art and commerce, vision and constraint. This article explores the point at which this tension is most apparent: The difference between an architect’s publicly recognised, “branded” work and his personal, less visible projects. Analysing how iconic buildings such as the Guggenheim, which create the “Bilbao effect”, are shaped by media and marketing strategies, he discusses how this process affects architectural autonomy and content. In contrast, he argues that “quiet” projects such as social housing, small chapels or private homes function as laboratories that uncompromisingly reveal the architect’s fundamental design philosophy, material experimentation and social sensitivity. Thus, he argues that an architect’s legacy should be sought not only in his loudest works, but also in his quietest whispers.

Media and Publicity:

High-profile buildings often gain notoriety through scale, striking form and relentless media attention. Governments and developers use architecture to brand their cities by commissioning “photogenic monuments“. The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (1997) is a paradigmatic example: “the wow factor” and global press attention made it “the most influential building of modern times” and led to the so-called “Bilbao effect” of landmark-oriented urban regeneration. Such landmark projects are designed from the outside in to capture the gaze of tourists and often emphasise spectacle rather than context.

Critics warn that this can lead to over-aestheticisation: architects seek photogenic forms primarily for media impact. In contrast, quiet or modest projects such as social housing, community centres or personal residences receive little attention. As Franck notes about Richardson’s work, the heroisation of famous buildings can “unwarrantedly overshadow ” other worthy structures nearby. In other words, public recognition and awards (from press reviews to architecture prizes) focus attention on a few iconic works, while many meaningful projects remain off the radar.

Constraints on Commissions:

Landmark commissions come laden with client demands, limited budgets and branding objectives. Mayors or royal candidates often explicitly ask for a “Sydney Opera House“ -style landmark. (Gehry describes Bilbao’s request: “We need the Sydney Opera House. Our city is dying”, to which he angrily replied “Where’s the nearest exit? I will do my best”). In such cases the architect has to compromise with stakeholders: they design to fulfil a promise (economic recovery, city prestige) rather than pure personal vision. Zaha Hadid’s work in the Middle East exemplifies this. Gulf leaders have used avant-garde forms to burnish their national image with “photogenic monuments”. These projects often prioritise image and function over experimentation. In contrast, smaller or independent projects allow for more original expression.

Frank Gehry has spoken of his early passion for social causes – he came to architecture “thinking it was a panacea ” for housing the poor – but he could not find “clients for social housing” in the market. Even today, he says, “I like to build social housing”, but adds that the fees for such projects are often too low.

Similarly, Pritzker Prize winner Shigeru Ban complained that architects “mostly work for privileged people” and consciously dedicated himself to disaster relief and low-cost shelters. In short, high-profile commissions often force architects to conform to client and commercial imperatives (brand image, cost, timescales), resulting in polished but constrained buildings, while side projects or personal commissions often reflect the architect’s true values (sustainability, local sensitivity or social purpose) and allow more freedom.

Design Philosophy Beyond the Agenda

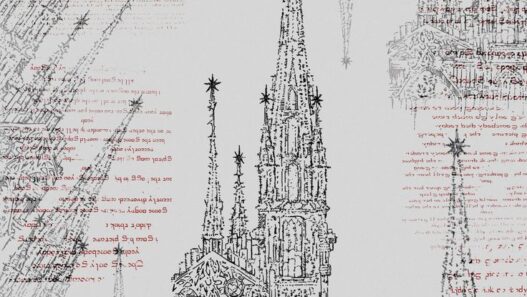

Studying an architect’s lesser-known work can reveal his or her fundamental design philosophy. These “hidden gems” – unbuilt proposals, personal houses, small community projects – often explore ideas that large commissions cannot.

Peter Zumthor’s works (he “refuses the spotlight”, as critics put it) consist almost entirely of modest, local projects: “few in number, small in size”, typically non-commercial residences, chapels or cultural institutions in Switzerland and neighbouring countries. In these projects, Zumthor follows a “conscientious” approach to exquisite craftsmanship and atmosphere: he “eliminates environmental elements to emphasise the innate composition ” of materials and light, embodying his belief that architecture is about the mystical essence that “beauty is real, true beauty“. Such intimate works, such as the Therme Vals spa or a simple tea chapel, capture spatial qualities (muted light, tactile materiality) that could be diluted in a blockbuster commission. More broadly, hidden projects can be laboratories where architects test material languages or programmatic ideas. For example, a small social housing project may be a prototype for sustainable construction methods, and a private residence may rehearse structural or geometric themes that will later be seen on a larger scale. These lesser-known works often contain “seeds of ideas” – the author’s purest intentions regarding space, form and detail – and are overshadowed by their more polished counterparts.

Authorship, Heritage and Cultural Capital

The tension between acclaim and personal significance reflects broader questions of architectural authorship and legacy. Architects accumulate symbolic capital (fame, reputation, awards) through high-profile work and media exposure, but these can come at the expense of artistic autonomy. As Frampton observes, architecture is the “least autonomous” art form and is always conditioned by external forces – clients, regulators and political goals. Some architects embrace this system, while others resist it.

Zumthor deliberately avoids fame and ostentatious style. Louis Kahn likewise seeks depth rather than popularity: critics note that “architects respect his buildings, but outside his profession his work, even his name, is little known”. In response, the famous “star architect” improves visibility: Zhao et al. describe how today’s practitioners often construct projects as Instagram-ready ‘influential online architecture‘ to boost their symbolic capital. However, they warn that an “overemphasis on capitalisation ” through such media-driven design risks eroding the integrity of the discipline.

Ultimately, an architect’s legacy is a complex mix of cultural capital – famous buildings, published ideas, unbuilt visions and even popular legend. Some, like Kahn or Wright, leave behind visionary drawings and writings as much as realised monuments. Others, such as Ban or Aravena, are known for exemplifying social values in their buildings and show how professional recognition can evolve from iconography to ethics. Architects’ silent projects, lectures, sketches and unrealised plans often take on new significance over time, reshaping how we read their careers. Ultimately, the most enduring legacy may be the sum of an architect’s contributions – the sum of the humble projects that most speak to their personal ideals and enrich the communities they serve.