The 15-minute city is a way of organizing urban life so that most daily needs can be met with a short walk or bike ride from home. It reshapes the city around time rather than distance and prioritizes easy access to living, learning, care, work, shopping, and recreation.

At its core lies the idea of chrono-urbanism, popularized by Carlos Moreno, which encourages people in cities to consider time as their primary design constraint. While this model gained momentum during the pandemic, it draws on long-term planning approaches that favor compact, mixed-use, and walkable neighborhoods.

Origins and Theoretical Foundations

Historical precursors of proximity planning

The first plans envisioned self-sufficient communities long before the concept of the “15-minute city” emerged. Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City proposed self-sufficient towns that balanced the advantages of urban and rural life with the proximity of daily services. Clarence Perry’s Neighborhood Unit later formalized the idea of a walkable catchment area for schools and shops, shaping twentieth-century neighborhood design.

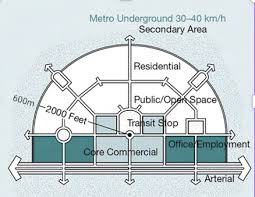

A similar trend emerged in the late 20th century. New Urbanism revived the 5- and 10-minute walk as a design criterion, while Peter Calthorpe’s Transit-Oriented Development model combined compact, mixed-use development with rapid transit. Both advocated for daily travel by walking, cycling, and public transportation instead of long car trips.

Before Paris and alongside Paris, other cities also experimented with time-based proximity under different names. Melbourne developed the 20-minute neighborhood concept as part of its metro strategy, and Portland created an index to expand “healthily connected” neighborhoods. Barcelona’s Superblocks reorganized street networks to bring services and public life closer together. Shanghai codified “15-minute community living circles” across the city in a guide.

Carlos Moreno and the invention of the 15-minute city

Carlos Moreno, an urban planner working at the Sorbonne, brought these elements together into a clear narrative based on time. In his work between 2016 and 2021, he defines a city where the six basic functions of urban life are accessible within a quarter of an hour on foot or by bicycle, framing proximity as a form of urban resilience and quality of life.

Paris brought this idea to the global stage. Under Mayor Anne Hidalgo, the city linked the reallocation of streets, “oases” in schoolyards, and local services to an agenda of proximity that became a reference point for other cities. This visibility also led to misunderstandings of the idea, but Moreno and city networks repeatedly clarified the issue.

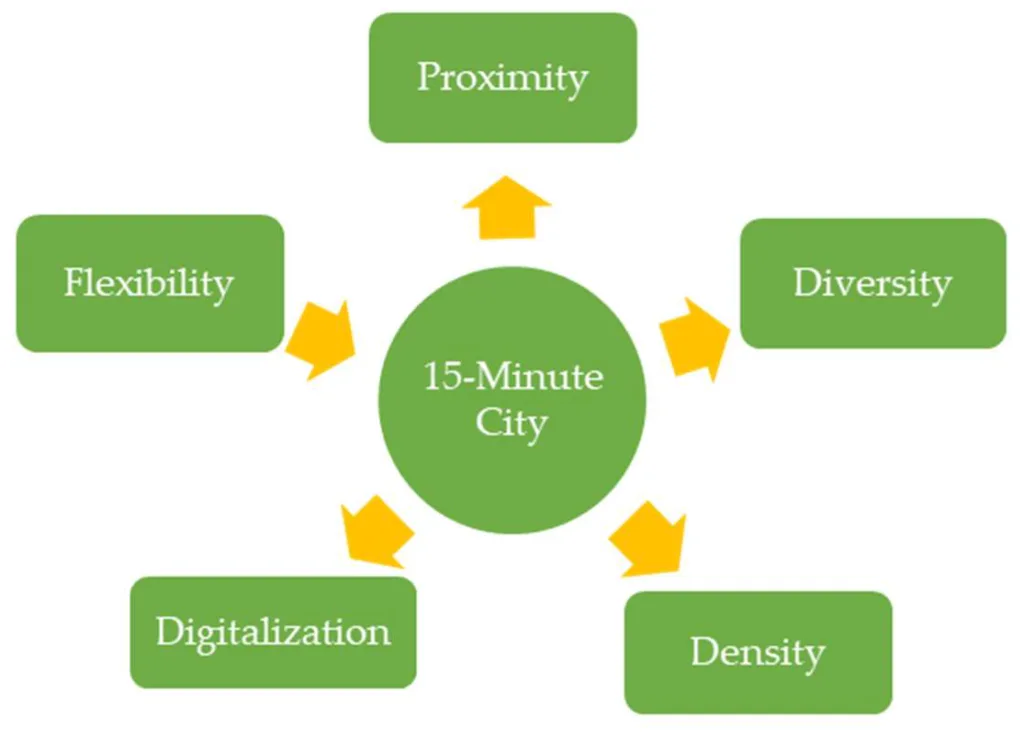

Basic principles: density, diversity, proximity, digitalization

Density

Density within a 15-minute frame is not about crowding. It is about achieving the right density of people and activities to sustain local services, transportation, and public life. Research and guidelines define density as a prerequisite for shops, schools, and clinics within walking distance and as a lever for reducing car dependency.

Diversity

Diversity means mixing land uses, housing types, and social groups to ensure neighborhoods are vibrant throughout the day and meet different needs. This reflects Jacobs’ call for mixed uses in short blocks and is seen today in composite accessibility metrics that check whether different destinations are truly close to each other.

Proximity is a planning principle. It measures access in minutes rather than meters and aims to shorten daily trips to important places. Studies define proximity as a shift toward human-scale planning, where walking or cycling distance determines how services are distributed throughout the city.

Digitalization

Digitalization is the connective tissue. Moreno’s model clearly relies on telework, online services, and data-driven management to complement physical proximity. A smart layer helps distribute services more equitably and reduces the need for long commutes by enabling certain functions to be accessed virtually by residents.

Conceptual critiques and debates

Equality and gentrification

Critics warn that proximity gains may already be concentrated in central or affluent areas, with very little change occurring in peripheral areas. Empirical studies link specific proximity improvements to the risk of gentrification and call for distribution tools that primarily target neighborhoods suffering from service deficiencies. Others argue that this framework should also include care trips and social infrastructure, which are typically carried out by women and caregivers.

Jobs, markets, and regional scale

Urban economists point out that labor markets and specialized services cover all regions. If a rigid interpretation limits opportunities, this may conflict with the way cities increase productivity. Commentators such as Alain Bertaud advise against treating each neighborhood as a completely self-sufficient unit and suggest combining local integrity with rapid regional mobility. For this reason, some policy bodies speak of an intertwined concept ranging from 15-minute neighborhoods to 30-minute regions.

Measurement and applicability

Researchers are creating standardized indices to test whether cities meet the 15-minute access requirement for different functions and often find unequal performance between services and populations. This study recommends prioritizing basic needs over lifestyle opportunities, clear criteria, and transparent trade-offs.

Public debate and misinformation

This concept has become intertwined with online myths that incorrectly equate proximity planning with travel restrictions. Independent fact-checking organizations and major media outlets have clarified that 15-minute cities are not about mandatory boundaries, but rather about optional access. This debate underscores the need for careful public communication when reallocating street space or changing traffic rules.

Key Components of the 15-Minute City Model

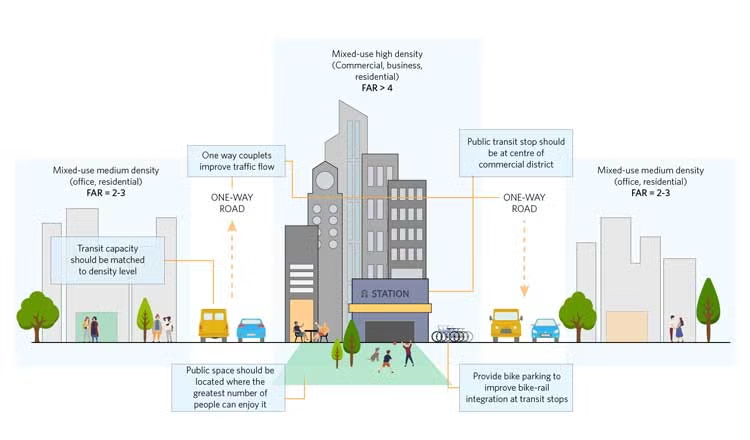

Mixed-use zoning and land use integration

What is it and why is it important?

Mixed-use brings together housing, daily services, small businesses, schools, and culture within the same walkable fabric. By bringing these functions together, it reduces the need for long trips, so most routine needs can be met nearby. Decades of evidence show that compact, mixed-use urban structures are associated with less car use and more walking and public transportation. This is the cornerstone of the 15-minute promise.

How does planning translate this?

Policy tools make the map compatible with daily life: context-appropriate density, form-based codes, a lack of middle-class housing, and transit-oriented blocks that ensure shops and services are located on main streets rather than in remote centers. Even traffic models now acknowledge that truly mixed neighborhoods generate fewer car trips than previously assumed under single-use zoning plans.

Success indicators and common criticisms

A functional mixed-use area is active from early morning to late evening, has short work chains, and has doors that open directly onto the street. The main risk is selective proximity, where central areas benefit from services while peripheral areas do not. The solution is to first distribute basic uses, then layer in diversity, so that the advantages of proximity do not become a luxury only the city center can afford.

Mobility infrastructure and active transportation

Networks designed for daily travel

Active mobility is not just an additional lane added to car roads. It is a continuous network that includes protected bike lanes of appropriate size for children and the elderly, quiet local streets, safe crossings, and roads providing direct access to public transport. Contemporary design guidelines establish clear standards for bicycle use and continuous protection for people of all ages in areas with high speeds or traffic density.

Speed management as design

Lower speeds are a life-saving geometry. International studies show a strong link between speed and crash risk, and cities that keep speeds around 30 km/h on local networks make walking and cycling safer and more attractive. These gains are not marginal additions, but structural elements of the 15-minute street hierarchy.

Integration of public health and transportation modes

Walking and cycling policies provide measurable benefits for health and climate, and yield the best results when combined with frequent public transportation. This ensures neighborhoods remain complete locally while also being connected regionally. Proximity does not turn into isolation in this way.

Public spaces, green infrastructure, and urban ecology

Street life as civil infrastructure

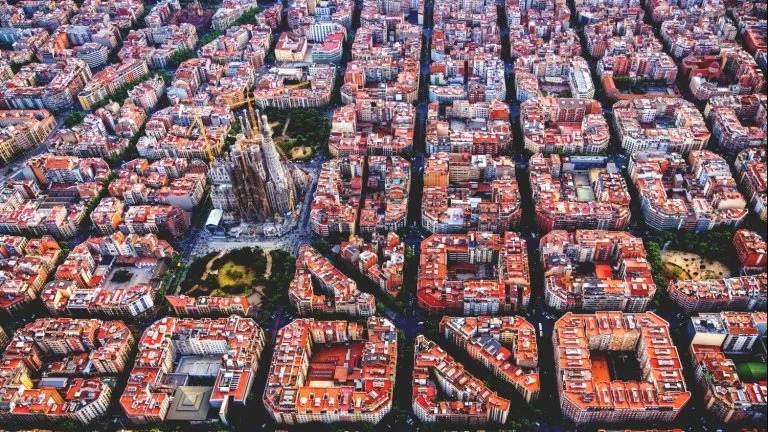

Squares, school streets, and superblock-style grids transform the area from transit traffic to public life. Assessments conducted in Barcelona show that these restructured fabrics are associated with increased walking and cycling and a calmer local environment, demonstrating that public space is the social engine of the proximity city.

Nature as the system layer

Green infrastructure cools heat islands, filters the air, slows rainwater runoff, and supports biodiversity, while also providing opportunities in daily life. Cities scale this with trees, permeable surfaces, bio-swales, wetlands, and green roofs; climate adaptation and energy benefits are documented in public guidelines and case studies.

Access standards and equity Health institutions recommend that residents have access to meaningful green spaces within a short walking distance, and recent European assessments monitor how equally this access is distributed. Here, equality is measured not by the total park area on the map, but by the distance covered on foot.

Digital tools, services, and smart city integration

Clear indicators and a common language

Smart layers help cities steer their proximity agenda with comparable data. The ISO 37120 series defines indicator sets for sustainable, smart, and resilient cities, enabling leaders to track whether neighborhoods are truly becoming complete, healthy, and connected.

Urban digital twins for scenario testing

Digital twins transform a city’s structure and flows into a live model. Singapore’s national-scale twin is used to test planning options, energy performance, and emergency scenarios before construction, aligning investments with real-world outcomes that residents will experience at the street level.

Mobility data standards that make choices visible

Open specifications enable people to discover nearby options in real time and assist organizations with right-of-way management. The Mobility Data Specification structures data exchange between city providers for shared fleets, while GBFS supports user-facing information for bike and scooter systems. Together, they make local mobility understandable and reliable.

Governance and trust

Digital proximity only works when citizens trust the system. Barcelona’s move towards open data, participatory platforms, and data sovereignty shows a way to align smart tools with democratic control rather than surveillance. Within a 15-minute framework, this ethos ensures that technology serves the public sphere, not the other way around.

Design Strategies for Architects and Urban Designers

Human-scale street networks and block design

What is it?

Human-scale networks organize streets and blocks to facilitate movement at walking and cycling speeds; they include frequent intersections, short blocks, and continuous facades that resemble open-air rooms. Authoritative guides frame streets as the city’s largest public space and define typologies, sections, and intersection arrangements that prioritize people and place over efficiency.

How does form shape experience?

Block size and network configuration determine how many route options people have and where activities are concentrated. Research on spatial syntax shows that spatial configuration predicts natural movement and street liveliness, while classical urban design literature emphasizes height-to-width ratios, enclosed spaces, and facade details as components of legible and inviting streets.

Design evidence base

Best practices codify continuous protection for vulnerable users, clear priority at intersections, and low design speeds as the backbone of human-scale networks. CROW’s guide and NACTO’s street guides detail widths, intersection shapes, and network hierarchies that provide safe and understandable daily travel for people of all ages.

Layered programming on ground floors and facades

What is it?

Layered programming brings daily activities to the ground floor to add vitality to buildings along the street. Active facades create visual and physical interaction between interior and exterior spaces through frequent doors and windows, short projection widths, and transparent edges. Global design references define these characteristics and the vocabulary of facades, furniture, and facade zones.

Why is it important?

Public life concentrates in places where the edges invite people to slow down, look inward, and participate. Jan Gehl’s long-standing research on public life shows that open and well-designed ground floors engage people and increase social activity, while blank walls discourage it.

Policy and coding frameworks

Urban design codes and plans translate this concept into rules for ground floor depth, minimum transparency, and corner emphasis, and these are typically linked to main streets and transportation corridors. The Urban Design Compendium and London policies provide clear criteria for active facades as a basis for mixed-use urban streets.

Filling, renewal, and intensification strategies

What is it?

Infill and renewal strategies transform underutilized parcels, surface parking lots, and single-use areas into mixed-use, walkable urban districts by intensifying the existing urban fabric where services are already available. The Retrofitting Suburbia research program documents how abandoned shopping malls, office parks, and big-box retail spaces are being converted into compact neighborhoods that support daily accessibility.

Density at the household level

The Missing Middle Housing concept refers to small, multi-unit building types that fit into residential neighborhoods, increasing options and proximity. This concept emphasizes not only height but also form and walkability, adding courtyard apartments, quad apartments, bungalow neighborhoods, and live-work units to the local mix.

Fine details

Accessory Dwelling Units add unobtrusive housing to existing lots and are increasingly supported by state and municipal policies. Handbooks and codes position ADUs as a tool that expands affordable housing while strengthening neighborhood cohesion.

Design for equality, accessibility, and inclusivity

What is it?

Inclusive design is a 15-minute framework where the shortest journeys are also the fairest journeys. Universal Design provides an interdisciplinary framework for evaluating environments so that they can be used by as many people as possible without requiring adaptation. Seven principles, developed from work pioneered by Ron Mace, form the conceptual foundation.

Legal and technical basis

Accessibility is based on applicable standards and technical guidelines. The 2010 ADA Standards establish the minimum scope and technical requirements for accessible buildings and facilities in the United States, while the UK’s Inclusive Mobility guide details best practices for pedestrian and public transport infrastructure. Together, these two guides define the floor, not the ceiling, of inclusive design.

Social perspectives that complete the picture

Global frameworks extend inclusivity beyond compliance. The WHO Age-Friendly Cities initiative identifies urban areas that support older residents, while UN-Habitat’s gender-sensitive planning guide addresses issues of safety, care visits, and access to services that are often overlooked in traditional plans. These perspectives ensure that proximity translates into real access for different users.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

The transformation under Paris and Hidalgo

What has changed and why is it important?

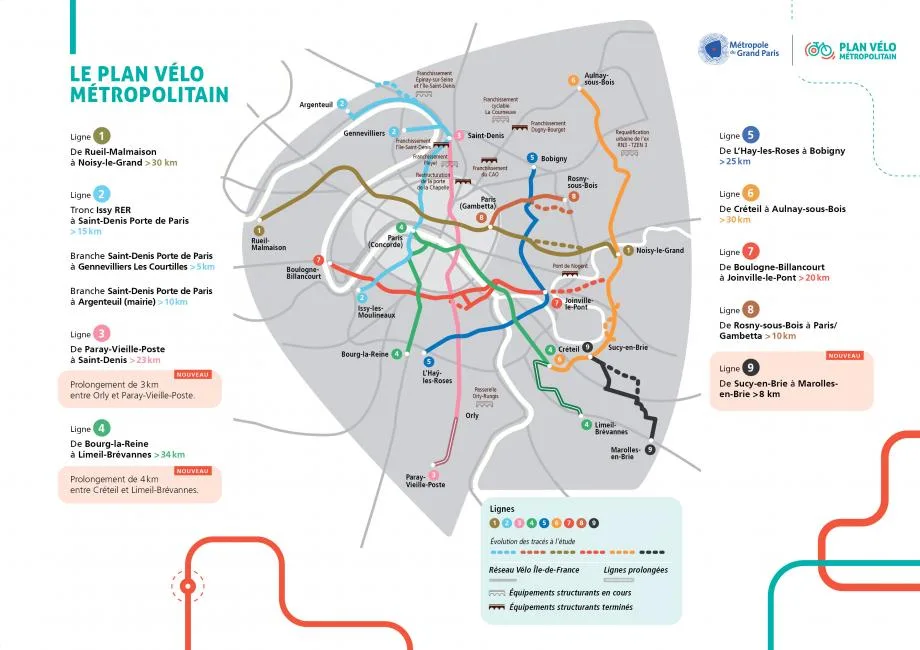

Paris redesigned its streets and schools as part of its daily civil infrastructure. The city invested in a continuous network of bike lanes and linked local quality of life to safe and short journeys. Official updates report that over 1,000 km of bike lanes have been built or maintained since 2020. The 2021-2026 plan envisions adding an express network to connect central suburbs. Independent reports indicate a strong increase in bicycle usage and acknowledge delivery delays putting pressure on the program.

Flagship programs that embody proximity Plan Vélo extends the permanent bike lanes created during the pandemic until 2026, while the OASIS schoolyard program transforms asphalt courtyards into green, cool community “oases” to combat heat risk and opens schoolyards to neighbors after hours. Paris’ open data portal now tracks the renovation of schoolyards site by site.

Paris’s next target

Citywide polls and policy summaries point to more car-free streets and a steady network expansion plan. In April 2025, residents supported banning cars on hundreds of streets. This is a sign that proximity policies have gone from pilot programs to public preference, even as debates over costs and access continue.

Barcelona’s accessibility mapping and lessons

Mapping accessibility as policy, not promotion

Barcelona’s superblocks are reclaiming space for people by reorganizing street networks. Peer review assessments and health impact studies position superblocks as a measurable improvement in accessibility rather than merely an aesthetic change, highlighting reductions in traffic exposure and potential gains in walkability and well-being.

From data sets to everyday life

The city publishes practical accessibility information that residents can use. Transport operator TMB monitors the accessibility status of stations in real time and reports on inaccessible metro stops. The municipality also maps inclusive playgrounds and updates its inventory as part of the 2030 public play strategy. These efforts demonstrate how “accessibility mapping” has become a service layer that guides daily choices.

A warning from the courts

The initiative faced legal and political challenges. In 2023, a Barcelona court ordered the cancellation of parts of the Consell de Cent pedestrian zone project on procedural grounds. Subsequent commentary and news reports debated the cost of the “Green Axes” model and whether it would be repeated in the future. This incident demonstrates that technical success must be accompanied by clear legal pathways and lasting coalitions.

Examples from Latin America, Asia, etc.

Bogotá: Barrios Vitales and proximity through a 30-minute perspective

Bogotá’s 2022-2035 land use plan promotes a compact, transit-oriented city and is implementing the “Barrios Vitales” pilot project to reclaim street space through tactical and permanent interventions. While the mayor’s office creates a complementary 30-minute city framework to balance local cohesion with regional connections, the latest analyses track air quality and public space outcomes in the pilot corridors.

Mexico City: UTOPÍAS as social infrastructure accessible within 15 minutes

Born in Iztapalapa, the UTOPÍAS network of multi-program large public facilities is now spreading throughout the city. Official sources describe this model as a form of socio-urban acupuncture that provides high-quality amenities close to where people live. By the end of 2024, the new city administration announced plans to expand to up to 100 facilities, aiming for local accessibility within short distances.

Shanghai and metropolitan Asia: “coding the life cycle”

Shanghai has officially adopted “15-minute community life cycles” and published a planning guide that defines service areas for daily needs and sets the equitable distribution of public facilities as a key objective. Academic and professional summaries emphasize the 15-minute walking distance as a spatial unit for the placement of shops, clinics, schools, and parks. Seoul’s research arm defines a related “walkable neighborhood unit” policy aligned with 15-minute goals, while studies in Tokyo examine how this model can be implemented in dense areas with rich public transportation options.

Failures, compromises, and lessons learned

Language and trust are important. In parts of the UK and North America, misinformation confused proximity planning with travel restrictions. Oxford officials removed the phrase “15-minute city” from documents to reduce tension while maintaining practical measures. Fact-checking emphasizes that this idea relates to optional proximity, not mandatory boundaries. The lesson here concerns communication: combine technical work with clear and repeated public statements.

Law, process, and implementation capacity shape outcomes

The Barcelona court’s decision regarding the Consell de Cent demonstrates that even popular street transformations can become vulnerable when procedural steps are skipped or challenged. Separately, the city has stated that limits have been placed on replicating certain green corridors due to costs and coexistence dynamics. Official compliance and long-term maintenance planning must be included in the design brief from day one.

Without targeted investments, the equality gap will persist

Assessments of Melbourne’s 20-minute neighborhoods reveal strong access to the city center, but inconsistent outcomes in peripheral neighborhoods, particularly in health and education. Proximity alone does not ensure equality; governance that prioritizes areas underserved by services and coordinates regional transportation is necessary, so that local cohesion does not turn into local isolation.

Paris reminds us that progress is not linear

Despite the large-scale reorganization of its streets and the significant increase in bicycle use, Paris faces delivery delays, retail and access issues, and ongoing political disputes. Referendums for hundreds of new car-free streets are gaining momentum, but these referendums coexist with implementation challenges that must be monitored in a consistent and transparent manner.

15 Minutes of the City’s Challenges, Risks, and Future

Corporate, regulatory, and governance barriers

Fragmented institutions slow down delivery

When transportation, land use, housing, health, and finance are siloed, even strong visions of connectivity can come to a standstill. Recent OECD studies emphasize that place-based agendas require multi-level coordination, stable financing, and performance frameworks that transcend departmental boundaries, rather than one-off pilot projects. To put it plainly, governance capacity is as decisive as design.

Laws and processes can undermine popular projects

Barcelona’s Consell de Cent green axis shows how legal procedures can overshadow success on the streets. Courts upheld rulings that parts of the pedestrian plan required formal metropolitan planning changes rather than a simpler licensing route, necessitating revisions and reminding cities that their designs must be legally compliant from day one.

Standards and data help establish legitimacy

Cities that publish comparable indicators and test scenarios in advance reduce policy risk. The ISO 37120 series provides a common language for monitoring services, resilience, and smart capabilities, while national-scale digital twins like Virtual Singapore enable organizations to model heat, flooding, or mobility options before making capital investments. This is governance by evidence, not slogans.

Socioeconomic inequality and spatial justice issues

Access is generally best where the advantage already exists

Assessments of Melbourne’s 20-minute neighborhoods reveal good proximity in inner and middle suburbs, but weaker access in outer suburbs, particularly in terms of health and education. Journalism and official analysis reach the same conclusion: outer growth areas face persistent deprivation in terms of services and transportation unless this gap is consciously closed through investment.

The risks of gentrification are real and context-specific

Peer-reviewed studies have linked some proximity improvements to displacement pressures, particularly when improvements are not paired with affordability and tenure protections. New frameworks propose integrating health and equity metrics into chrono-urbanism, ensuring that proximity gains do not overlook low-income residents.

How mobility deserts increase inequality

In areas without frequent bus services and safe walking options, residents are forced to travel longer distances and pay more to meet their basic needs. Recent reports on Melbourne’s outer suburbs show how limited evening and weekend services reinforce disadvantages. This serves as a warning to all cities that view proximity as a branding tool without addressing network issues.

Climate resilience, adaptation, and sustainability

Compact design reduces demand and paves the way for cleaner transportation methods

The IPCC has concluded that walkable mixed-use neighborhoods and transit-oriented developments reduce energy demand and enable the transition to active transportation. This is one of the most straightforward mitigation tools available to city governments and lies at the heart of the concept of proximity.

Cooling cities is a matter of life safety. A Europe-wide study published in The Lancet estimates that increasing urban tree cover by approximately 30% could significantly reduce heat-related deaths. EU and EEA briefings point in the same direction: more shade, more evapotranspiration, fewer dangerous heat islands.

The scale of shared benefits justifies it

When cities combine cleaner energy with street redesign and low-emission transportation, C40’s analyses predict significant reductions in emissions and gains in health. Adaptation studies add that new governance models are needed to finance, sustain, and ensure the reliability of these climate actions for decades to come.

The next evolution: 10-minute cities, hybrid models, or digital proximity

Proper sizing of the time ring

There is no single clock speed. Some places pursue 10-minute city centers, while others create 20-minute neighborhood programs, and multi-centered regions aim for 30-minute cities where homes and important workplaces are connected by rapid transit. The principle remains constant: local integrity within regional opportunities.

Hybrid models combine local life with metropolitan scale

Urban economists warn against each region becoming a self-sufficient island. Studies indicate that most x-minute work studies do not sufficiently consider the geography of employment. The future looks like a fabric woven together by dense, mixed local areas connected by rapid regional mobility, rather than a patchwork of disconnected villages brought together.

Digital proximity will mature this idea

The next wave of proximity is not claimed, but measured and simulated. When combined with ISO city data standards and human-centered smart city guidelines, digital twins like Virtual Singapore allow planners to test trade-offs and publish results for residents to review. Reliable digital layers will determine whether proximity planning remains a movement or becomes standard practice.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.