A door is more than just something that closes a hole in a wall. It is a small architectural element that controls the flow of people, air, noise, light, and energy. Early dwellings used whatever was at hand to cover openings: leather, woven mats, and later wood or stone. Because if you can close off a space, you can determine who can enter it and when. This simple act of closing and opening transforms a house into a social tool.

When people began marking a place as “inside,” they also marked a line where the inside met the outside: the threshold. Crossing this line became loaded with meanings such as welcome, warning, purity, and privacy. Anthropologists call this intermediate zone the boundary; it is a stage where rules can be reversed and identities can change. Doors are located on this line and allow for daily rituals (knocking on the door, greeting, taking off shoes).

The Origins of Doors in Human Settlements

Permanent settlements transformed open spaces into controlled passages. When walls, streets, and rooms are planned, a controlled entrance is needed on the scale of a city gate, temple gate, or house gate. Solid doors are seen alongside monumental buildings where stone, wood, or bronze can provide symbolic weight and physical security.

- Threshold: the social boundary where rules change.

- Material leap: in architectural form, leather/textile → wood/stone/metal.

- Dual role: doors as functional tools (security, climate, circulation) and symbolic tools (rituals, status, myth).

From the Beginning to the Threshold: Prehistoric Beginnings

In the first huts and caves, people blocked wind and animals with movable skins, woven curtains, or bound branches. These were not hinged “doors,” but rather movable covers that created a controllable boundary when needed. The transition to rigid, hinged doors occurred later, alongside heavier, planned structures.

Even before actual doors appeared, communities regarded the threshold as a sacred space. Crossing the threshold was an act of hospitality or taboo. This “in-between” quality later made door thresholds ideal for ceremonies (such as blessings performed at the door or rules about who could enter). The term liminality, used by linguists, helps explain why door thresholds possess a ritual power far beyond their physical dimensions.

Neolithic portal tombs (dolmens) use two long upright stones, known as “portal stones,” and typically a large capstone, usually closed, to mark a symbolic entrance. These are interpreted not as traffic control devices in daily life, but as gates to other realms. The idea that a framed passageway could express more than just its functional meaning is already present here.

Symbolic and functional beginnings

The ancient Egyptians carved false doors into tomb walls: stylized frames with doorposts, lintels, and shallow niches. The living would leave offerings here; it was believed that the ka of the dead passed through here. This is an architectural element that appears to be a purely symbolic threshold in terms of hardware, requiring no hinges.

As cities grew, symbolism and functionality merged. Monumental temple and palace doors had to be impressive and functional—they had to close off sacred spaces, proclaim authority, and withstand weather and war. That’s why we see heavy wooden panels, metal bands, and hinges—technology evolved to meet the ritual and political demands placed upon the door.

Even today’s projects ask these two questions: What purpose should this door serve? What should it represent? The answer shapes the hardware, scale, and ceremony—whether it’s the modest examination room door of a clinic or the main entrance of a public building.

Doors in Early Civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley

Texts and artifacts show how doors became part of state administration. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu builds a massive cedar door for Enlil’s temple—the wood is sacred, while the scale carries political meaning. Later, Assyrian gates, such as the Balawat Gates, covered cedar leaves with bronze strips inscribed with royal campaigns: the gate protects the threshold while telling the story.

Egypt offers us both: wooden doors for rooms and courtyards, and stone-carved false doors focused on the other world. The false doors in the museum, dating from the Old Kingdom period, anchor the votive chapels; their carved frames and inscriptions show the door as a meeting place for the living and the dead. Parallel to this, the transition from textile curtains to the use of hard leaves follows the rise of large stone architecture.

The city plans of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa reveal a practical logic behind the placement of gates. Most houses open onto side streets rather than main roads to protect privacy and filter out dust and noise; the doors close off the courtyard houses inward, focusing on family life. Reconstructions and field notes even mention wooden shutters as a closing technology. This is a choreography across the city: doors have moved away from display and toward control.

- Security and Message: Heavy leaves and metal bands are not only strong, but also performative. Consider data centers or embassies: visual language still signals control. (Old model: bronze-banded doors.)

- Privacy from the design stage: If you want quiet interiors (clinics, residences), orient the doors toward secondary circulation. The timeless Harappa trick of facing streets instead of boulevards.

- Ritual at the threshold: In places where thresholds are important (schools, care homes, places of worship), design the transition—light, steps, canopy, or inscription—because people perceive doors not just as an opening, but as a moment. (Old model: fake door as the focal point of the ritual).

Doors as Cultural and Spiritual Symbols

In different cultures, doors are not merely a means of closing; they symbolize the transition from one state to another. Anthropologists define this “in-between state” as liminal, meaning “on the threshold.” This is a moment when identities and rules can change before being reshaped on the other side. Therefore, many rituals are performed at door thresholds, from blessings and greetings to taboos about how, when, and who can pass through.

Since thresholds separate ordinary spaces from extraordinary ones, they often carry intense meaning in both religious and civil life. Passages and doors indicate that you are leaving everyday life behind and entering an area where different values prevail—sacred spaces, royal palaces, or places that hold collective memory. The architecture of the passage (frame, inscription, scale, material) expresses this change as clearly as any sign.

Rituals and Sacred Doors in Temples and Shrines

In Japan, the torii marks the boundary of a Shinto shrine; passing under the torii signifies entering the sacred area. The simple pillars and lintels of the gate do not serve a “protective” function; they merely mark a threshold where behavior and attention must change. Official temple guides and reference sources clearly define the torii as the boundary between the mundane and the sacred.

In South Asia, the torana and the rising gopuram perform similar functions. The stone toranas at the Great Stupa of Sanchi choreograph the entrance movement to the Buddhist temple, while the carved beams direct the body and narrate the doctrine. In South Indian temples, gopurams function as monumental entrance towers that intensify symbolism and ritual order at the transition point from the city to the temple.

In Catholic Rome, the Holy Door (Porta Sancta) is sealed most years and opened ceremonially only for the Jubilee. Passing through this door is no simple matter; it is a pilgrimage journey—the embodiment of the theology of mercy and welcome that marks the beginning of the Holy Year. The Church’s own Jubilee guide and major announcements emphasize the role of this door as the most visible sign of the ceremony.

Boundary Areas as Thresholds in Myth and Folklore

Ancient Rome personified the power of passageways in Janus, the god of doors, passageways, and beginnings. The doors of his temple (Janus Geminus) were kept open during times of war and closed during times of peace. This state ritual had turned the threshold into a national barometer. The god’s two faces and the government’s public “door policy” had merged cosmology with politics.

Folklore generally treats thresholds as protective boundaries. In many vampire stories, a creature cannot enter a house uninvited; the door is not merely wood and hinges, but a social contract that grants or denies passage. This rule varies from region to region, but reliable summaries reveal the continuity of this rule in modern storytelling.

Hindu mythology takes this idea even further: Vishnu’s avatar Narasimha kills the tyrant Hiranyakashipu at twilight, at the threshold of the palace, neither day nor night, neither inside nor outside, using every borderline condition of immortality. The story highlights the threshold as a place of transition where normal protections are lifted.

Symbolic meanings: Power, Exclusion, and Invitation

Power. Heavily defended medieval gates—recessed passageways, drawbridges, and portcullis—were architecture’s way of declaring who controlled the entrance. Such mechanisms were more than barriers; they displayed authority: your experience with the ruler began at the gate. Technical histories detail how these entrances concentrated both defense and display in one place.

Exclusion. Doors can also encode social boundaries. The Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg confronts visitors with two separate entrance gates labeled “White” and “Non-White,” reflecting the laws that once segregated opportunities and access. The museum’s own educational materials and academic commentary document this staged shock as an educational threshold.

Invitation. Other doors also perform the welcome ritual. In Jewish homes, after the blessing ceremony, a mezuzah is placed on the right doorpost. This serves as a daily reminder of the covenant and commitment when entering and leaving the home. The Catholic tradition of the Jubilee invites pilgrims through the Holy Door as a gateway to reconciliation. In both cases, the act of passing through the door becomes a small ceremony of belonging.

A design lesson from the real world: If a door has meaning (such as sanctity, security, remembrance, or hospitality), design the door itself—not just the door leaf as an accessory—but the passageway itself (approach, frame, inscription, sequence). This example dates back to ancient times; its effect on people’s behavior when passing through a door is immediately apparent.

Material evolution and technological innovation

Wood, stone, bronze: identity creation

In the oldest monumental structures, doors evolved from leather and woven mats into swinging, impressive solid wings. In Mesopotamian palaces, long cedar doors with narrative bronze strips were used, literally wrapping the stories of royal power around the moving surface. Although the wooden parts have been lost, the bronze strips have been preserved in museums and show how metalwork strengthened a door and at the same time gave it a “message.”

Egypt adds another dimension: the door, as a sacred mechanism. Stone bolts and door hardware are seen in the temple context, and even miniature stone bolt models (such as the lion-headed bolt in Met) show how doors were ritualized and secured. In domestic and public life, as architectural scale increased, hardwood bars gradually replaced textile products and introduced a true swing or pivot movement into everyday living spaces.

In the Greco-Roman world, bronze and iron hardware developed around wooden frames. Archaeological records show bronze hinges and pivot sockets, and stone adjustments for pivots and frames have been preserved in Pompeii thresholds. The logic of craftsmanship—posts, rails, panels, supports, and ironwork—has produced many Roman doors that are familiar to us today. Britannica notes that this tradition extends to modern carpentry.

Hinges, locks, and mechanical developments

Before modern hinges came into existence, many ancient doors pivoted on vertical pivots set into thresholds and lintel sockets. This was a simple bearing capable of supporting heavy weights at city gates and courtyard entrances. As metalworking advanced, bronze strip hinges and joints became widespread throughout the Roman world, evolving into the multi-leaf hinge families we still use today.

Security has evolved from bolts to mechanisms. The Egyptian wooden pin lock, often referred to as the “Egyptian lock,” is a sophisticated ancestor of the modern cylinder lock. It used pins of varying lengths and gravity to block the wooden bolt until it was lifted with a keyed device. Linus Yale Jr.’s innovations in the 19th century miniaturized and metalized this principle, giving rise to the compact pin cylinder that dominates today’s door hardware.

New types of doors also emerged to solve environmental problems. Patented by Theophilus Van Kannel in 1888, the revolving door reduced air currents, noise, and crowding in busy lobbies, becoming a symbol of skyscraper entrances and energy-efficient design long before the term even existed.

The Rise of Industrialization and Mass Production

Industrial milling and catalog sales standardized this craft, which was largely a local trade. In the early 20th century, flat doors joined paneled doors in mass-market carpentry catalogs, and as builders sought lighter, cheaper, and faster-to-install doors, the “hollow, flat panel” became widespread. In 1924, William H. Mason invented Masonite, which provided smooth, dimensionally stable veneers ideal for factory-made flat doors.

Standardization quickly merged with safety science. Fire-resistant assemblies emerged with their own standards and tests—NFPA 80 for installation and maintenance requirements and UL 10C for positive pressure fire testing—thus transforming doors from mere closing elements into part of a building’s passive life safety system. The modern code ecosystem integrates these standards through the IBC, making “door + frame + hardware” a certified assembly.

Mass production has also changed performance expectations. While hollow cores are economical and easily transmit sound, solid cores or special cores offer better acoustic performance; designers now balance cost, weight, fire resistance, and sound control rather than treating the door leaf as a single material. Nevertheless, a long process is evident: from cedar and bronze strips to particleboard laminates and tested assemblies, doors continue to fulfill both the practical burden of security and the cultural function of hospitality.

Doors in Architectural Theory and Design

Philosophical Readings of the Door: Heidegger and Bachelard

In phenomenology, a door is not merely an object that opens and closes; it is a way of thinking about how life unfolds between the inside and the outside. Martin Heidegger relates doors to the concepts of boundary and dwelling: a boundary is not merely the edge where something ends, but the place where something begins to emerge. From a design perspective, the door threshold is where space acquires meaning; it is where a room begins, where hospitality begins, where the conditions of an institution are defined. Therefore, thresholds feel charged even before one touches the door handle.

Gaston Bachelard writes about the emotional life of homes; he explains how small accessories like locks, drawers, and cupboards sustain our sense of intimacy. When read alongside his ideas about doors, his argument is simple yet powerful: Doors shape our dreams. A locked door not only provides security, but also creates a space for dreaming, privacy, and a sense of “my place.” The poetic qualities of a door—its texture, weight, key, sound—become part of our experience of shelter.

When these ideas come together, they provide designers with a clear summary. A door can bring a world together: it can make room for belonging (Heidegger’s concept of boundary as a starting point) and protect inner life (Bachelard’s concept of intimacy). In situations where a project requires dignity, comfort, or care, the door is not a detail; it is the stage for the first encounter.

Doors in Modernist and Postmodernist Discourse

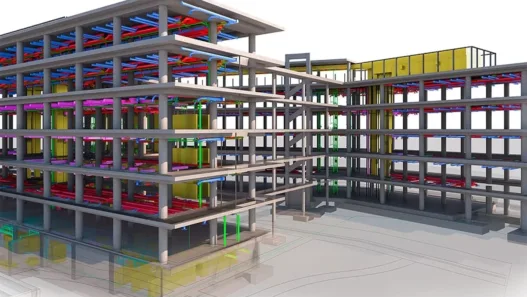

Modernists redefined the role of doors by redrawing the plan. Le Corbusier’s “five points” severed the old connection between load-bearing walls and room partitions, enabling the creation of open floor plans; when walls became movable, doors could be fewer in number, larger, lighter, or sometimes disappear within sliding panels. The door transforms from a structural necessity into a spatial choice.

Glass-walled houses have almost entirely transformed their entrances into frames. Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House and Philip Johnson’s Glass House treat the exterior facade as a continuous transparency; the door becomes a delicate cut in the glass curtain. Passing through the door feels more like a ritual than a mechanical act: step forward, pull, and suddenly the view appears “inside.” These houses taught generations that a door could be almost invisible yet still carry great symbolic weight.

Post-war critics challenged the naive meanings of the concept of “transparency.” Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky distinguished between literal transparency (being able to see through) and phenomenal transparency (being able to read multiple layers simultaneously). A glass door may be transparent in the literal sense, but it can be complex in terms of how it is perceived—framed views, overlapping planes, reflections. Postmodern discourse kept this debate alive by treating the entrance as a sign in a field of signs: not just a hinge, but a message about access, identity, and taste.

Open and Closed Plans: Transparency Policy

Open spaces promise equality and comfort, but they also transform power and privacy. Beatriz Colomina demonstrates how modern architecture blurs the boundaries between public and private spaces by transforming homes and institutions into exhibition spaces through the use of glass and media. From this perspective, a transparent door is not neutral; it takes a stance on who can look inside, who will be seen, and who must perform to be seen.

Workplace studies add a practical caveat. When offices remove doors and partitions to encourage “collaboration,” measured face-to-face interaction typically decreases while electronic messaging increases. Social contracts like knocking, entering, and exiting have emerged to regulate behavior in useful ways. Designers are now combining glass doors, partial screens, and quiet rooms to allow people to choose when to be visible and when to focus.

Transparency in civil and cultural buildings can be welcoming, but it must be balanced with control. Glass is merely a tool; the real question is what the intersection point signifies and what it enables. A good project organizes thresholds, canopies, entrances, and framed views in layers, so that openness does not compromise dignity or security. In this spatial policy, the door is a small part with big consequences.

Cultural Differences in Door Design

In different cultures, doors embody the local climate, craftsmanship, and social norms. Throughout humid summers or snowy winters, a door’s function changes: ventilation or sealing, filtering or blocking light, welcoming or slowing crowds. This is why the paper-covered panel in Kyoto, the tiled entrance gate in Isfahan, and the carved stone door in Chartres feel so different: each is a cultural solution to the same problem—how to transition from one world to another.

Designers can view these variations as a toolbox. Sliding panels teach flexibility and daylight utilization; monumental portals demonstrate how meaning can be staged at the entrance; minimalist interiors remind us that sometimes the best door is the one that goes almost unnoticed until we miss it for privacy or acoustic reasons.

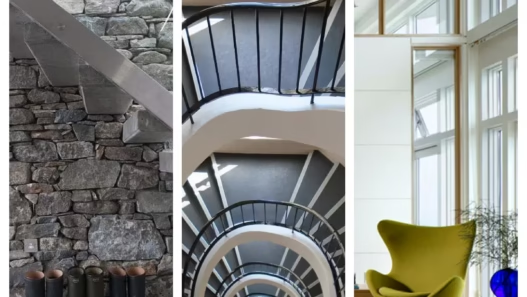

Sliding Doors in Japan: Aesthetics and Spatial Logic

Shoji (semi-transparent paper mounted on a wooden frame) and fusuma (partitions covered with opaque paper) slide rather than open and close, allowing the size of rooms to be adjusted as desired and softening light as if it were passing through a lantern. Their materials and functions are standard enough to be included in reference works: shoji diffuses light when closed; fusuma, meanwhile, serve as room dividers in interior spaces.

Traditional houses are measured using tatami mats (approximately 180 × 90 cm), so panels and openings are aligned according to this grid. The result is a plan that you can “arrange” by moving the leaves: open for gatherings, closed for sleeping or working. This tatami discipline still forms the basis of classic shoin rooms, where ornate fusuma cover all the walls.

Museums preserve the artistic aspect of these doors: Fusuma panels painted by artists from the Kano school once defined all interior spaces, proving that a “door” could be both architectural and pictorial. JAANUS describes the fusuma structure (wooden frame, layered paper) and sliding rails; the Met Museum houses famous multi-panel examples.

Real-world application: When you need an adaptable space with soft daylight (such as small apartments, clinics, classrooms), use this logic: Sliding panels on a consistent module, semi-transparent where light is important, and opaque where privacy is required. This idea dates back centuries, but it still holds true today.

Magnificent Entrances in Islamic and Gothic Architecture

In Persian Islamic architecture, monumental portals are typically framed by a pishtaq (an emphasized, rectangular portal screen) and take the form of an iwan (a vaulted space open on one side). These entrances are richly decorated with tiles, calligraphy, and muqarnas (honeycomb-like three-dimensional carvings), transforming a structural opening into a ceremonial threshold. While authoritative dictionaries and site records document the pishtaq/iwan pairing, museum collections describe muqarnas as the honeycomb-like vocabulary of portals and domes.

The most typical example of this is the Imam (Shah) Mosque in front of Naqsh-e Jahan Square in Isfahan: its soaring gate symbolizes the transition from a crowded square to a sacred space, and this effect was also taken into account when the site was added to the World Heritage list. This lesson is theatrical but functional: a gate can direct urban crowds, frame inscriptions, and intensify the experience before entering the courtyard.

Gothic portals function differently: the stone “curtains” on the door jambs and the tympanums filled with stories teach you something as you enter. In Chartres, the sculpture on the royal portal reveals theology at the threshold: the majestic Christ in the tympanum, elders in the archivolts, patriarchs in the jambs—thus the passageway also serves as a catechism. Encyclopedic and educational resources explain how these pieces fit together and why they were important to medieval audiences.

Design Summary: When the entrance needs to communicate (public buildings, campuses, places of worship, etc.), think of the portal as a program. Use framing, depth, inscriptions, or layered ceilings to emphasize not only the change in space but also the change in area.

Contemporary Minimalism and the Disappearance of Doors

Some contemporary buildings strive to create nearly seamless interior spaces by utilizing landscape-like floors, minimal partitions, and long sightlines. SANAA’s Rolex Learning Center is described by designers and institutions as a “single space” gently divided by slopes. This demonstrates how circulation, topography, and furniture can replace multiple doors without losing orientation.

However, removing doors also brings some disadvantages. Workplace studies show that when boundaries are removed, face-to-face interaction decreases while digital messaging increases; the much-praised “open plan” is not a universal solution. Research from Harvard Business School and the Royal Society quantifies these effects and suggests designs we can choose from: quiet rooms with doors alongside open spaces.

Practical panel: conceal the door when it aids flow (pocket doors that disappear into the wall), reveal it when a control signal is needed (acoustic or access-controlled panels), and adjust privacy and light by mixing transparent, semi-transparent, and opaque layers. Even the modest pocket door, defined as a panel that disappears into the wall cavity, is a modern cousin of the sliding logic described above.

The Future of Doors in the Digital Age

Smart Doors and Technological Interfaces

Phones and wearable devices are becoming essential. Apple’s Home Key feature adds an ID to Wallet, allowing you to unlock supported locks with a tap and even enable “Express Mode” for hands-free NFC access without Face/Touch ID at the moment of use. This convenience can be disabled, but the main idea is clear: your ID now travels with the device you already carry.

Interoperability is finally maturing. The Matter standard defines a common “Door Lock” profile and operates over Thread or Wi-Fi, enabling a single lock to communicate with multiple ecosystems. Developer documentation and recent product launches indicate that Matter-over-Thread locks are widely available and reduce supplier dependency.

Next up is proximity-sensitive, hands-free entry. Ultra-wideband (UWB) can measure distance with enough precision to unlock the door only when you are right in front of it, and the upcoming CSA “Aliro” standard aims to turn phones/watches into cross-platform digital keys for doors and readers. As vendors adapt, the first versions are expected to be released by 2025.

Design Summary: Treat the door as an interface. Display its status (locked/unlocked, latched/unlatched), support multiple credentials (card, phone, watch, code, key), and schedule updates. The latest example is Level’s newest lock, which adds Thread, Matter, Home Key, and built-in sensors; this signals the arrival of the “portal as a product.”

Security, Privacy, and the Evolving Concept of Access

New capabilities bring new threats. Researchers have demonstrated low-latency Bluetooth Low Energy relay attacks that can deceive “phone key” systems. To prevent these attacks, measures such as UWB range determination, server-side anomaly detection, and flight time controls can be taken. Don’t assume that “Bluetooth + phone” is sufficient; combine proximity controls with speed limits and warnings.

Commercial doors still rely on proven building code ecosystems. UL 294 certifies access control units and specific exit behaviors; in the field, modern readers use OSDP (now an IEC standard) instead of unsafe legacy wiring and improve encrypted, controlled communication between panels and peripherals. Consider these as the fundamental elements that form the basis of the telephone keypad experience.

The privacy law treats access logs as personal data. In the EU/UK context, access logs may fall under the scope of GDPR/UK GDPR; this entails obligations regarding legal basis, minimization, storage, and the right of access. Regulatory bodies explicitly expect access controls and logs to be manageable and auditable. Set up configurations for data retention, export on demand, and clear administrative oversight within the system from day one.

Consumer labels and secure default settings help at home. The criteria established by NIST for the US IoT cybersecurity label emphasize practices such as unique identifiers, secure updates, and strong data protection. Use these as a checklist when selecting smart locks and bridges for your home. Also, check whether the platform supports core features (such as PIN/code management) across ecosystems; real-world users still encounter shortcomings.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.