Context of the Vertical Target

The Historical Background of the Evolution of Skyscrapers

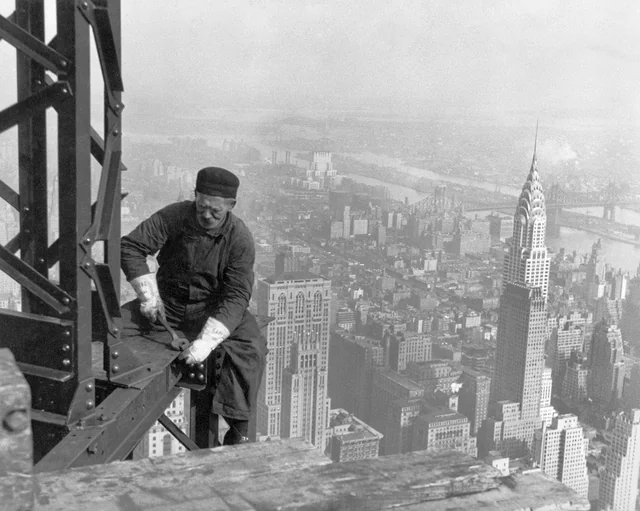

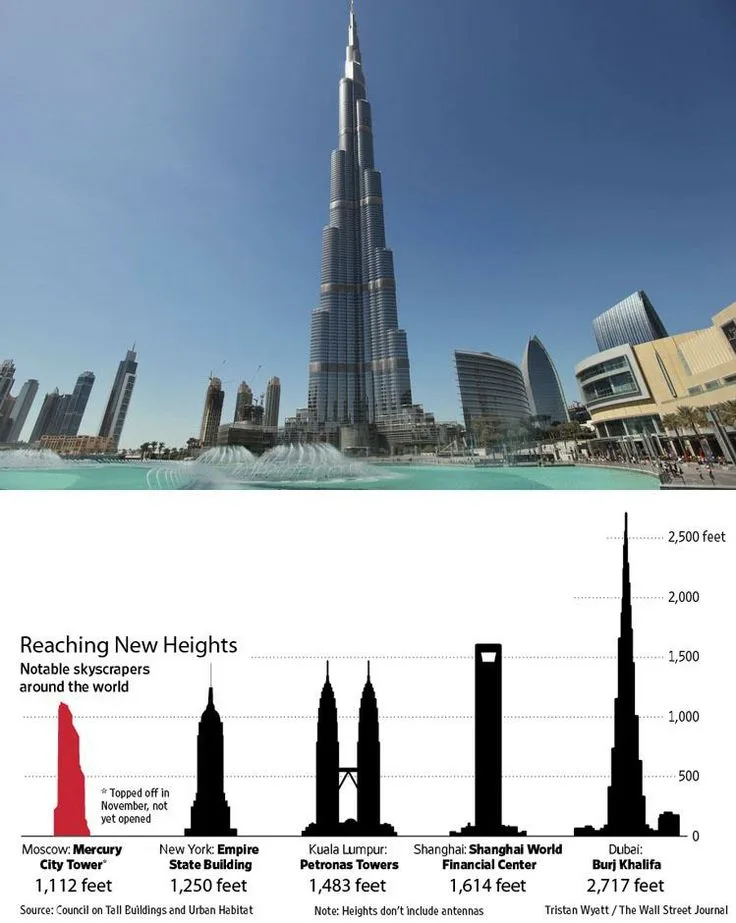

Skyscrapers emerged as cities ran out of horizontal space and new structural confidence was discovered. In the late 19th century in Chicago, metal frames replaced heavy stone walls, allowing buildings to rise without collapsing under their own weight. Elevators eliminated psychological barriers to height, and the idea of buildings as vertical neighborhoods became plausible for both engineers and ordinary citizens. The Home Insurance Building is often cited as an early turning point that changed everything, due to its use of a metal skeleton instead of stacked, load-bearing stone.

As the 20th century progressed, steel frames, wind bracing, and fire resistance became a common toolkit. This process, which seemed like a race for victory, also meant the continuous improvement of methods: lighter frames, sturdier cores, smarter facades, and safer structures. Height became a kind of public theater for private capital; each additional floor translated into rentable space and cultural appeal. This connection between technology and finance meant that skylines would reflect economic cycles and artistic tastes.

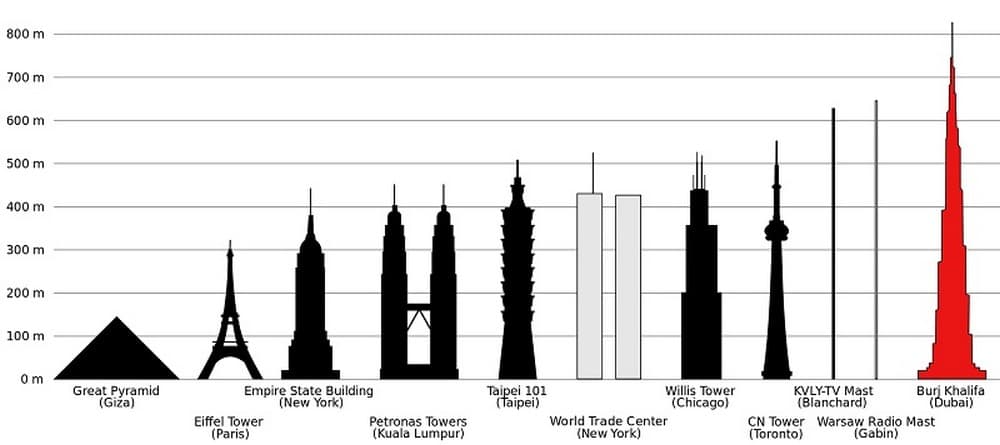

Today’s “megatall” towers, including the Burj Khalifa, are heirs to this tradition stretching from Chicago to New York, but they are based on a new structural logic. Instead of a single tube or simple frame, they distribute forces through shaped plans and adjusted cores that direct the wind around the building. Here, the story of height transforms into a story of geometry and aerodynamics; this shift presents extreme height as calm and controlled rather than reckless.

Dubai’s Urban Vision and Economic Strategy

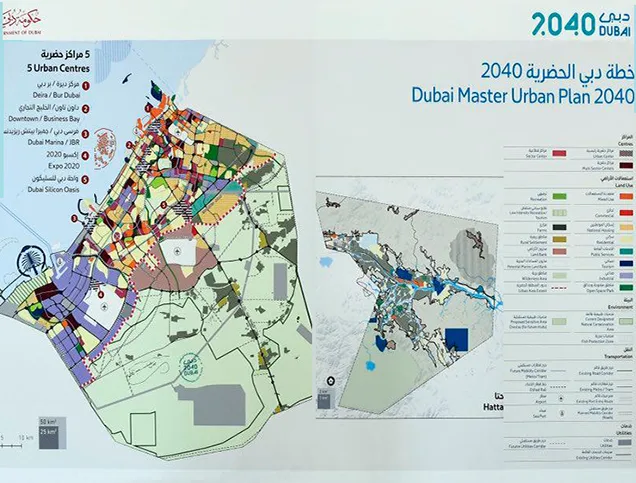

Dubai’s skyscraper era is not an architectural coincidence but an economic strategy. The city’s D33 agenda clearly links urban glamour, infrastructure, and entrepreneurship to a plan to double the economy by 2033 and position Dubai among the world’s top three cities for living, investing, and working. A skyline filled with familiar “Dubai” silhouettes serves as both a signal and a platform: promising a certain lifestyle and pace of business while attracting capital, talent, and visitors.

In addition to growth targets, Dubai’s 2040 Urban Master Plan aims to rebalance the city’s livability by expanding green spaces, increasing resource efficiency, and connecting healthier neighborhoods. In policy terms, there is a desire to transform the image of a car-centric, shopping mall-based city into a more walkable, inclusive, and resilient city. The goal is to maintain a global scale without compromising human comfort, which is a particularly delicate balance in a hot climate metropolis.

Tourism is at the heart of this strategy. Campaigns and new visa routes have transformed Dubai from just a stopover into a destination in its own right, and visitor records have helped validate investments in iconic structures and areas. The skyline is a marketing asset, but it only works when the ground-level experience (transportation, shade, cultural spaces, affordable hotels) keeps pace. Dubai is currently striving to manage this tension effectively.

The Symbolism of Height in Global Architecture

Towers have always been the loudspeakers of silent messages. A very tall building concentrates ideas such as nationhood, corporate power, and technological superiority into a single silhouette against the sky. From New York to Kuala Lumpur, and on to Dubai, the higher you go, the more the building acts as a billboard reflecting the values of those who built it. Even if the facades differ, the common message is desire—the desire to be seen, counted, and remembered.

However, symbols change over time. In the 21st century, a record-breaking structure must not only be tall, but also embody efficiency, cultural harmony, and environmental sensitivity. While Burj’s plan geometry references regional forms, its structural core elegantly solves wind and stability issues with an economical approach. This duality symbolizes both local identity and global sophistication. The lesson to be learned here is that today, height must convey a narrative about identity, climate, or public life; otherwise, it risks being perceived as a structure that can be summarized in a single sentence.

Culturally, the meaning of skyscrapers has become more ambiguous. They can still evoke a sense of heroism, but they also raise questions about inequality, carbon emissions, and who the sky actually belongs to. Cities increasingly expect tall buildings to deliver returns through public spaces, transportation connections, or environmental performance, so that the symbolism of height does not overshadow the reality experienced below.

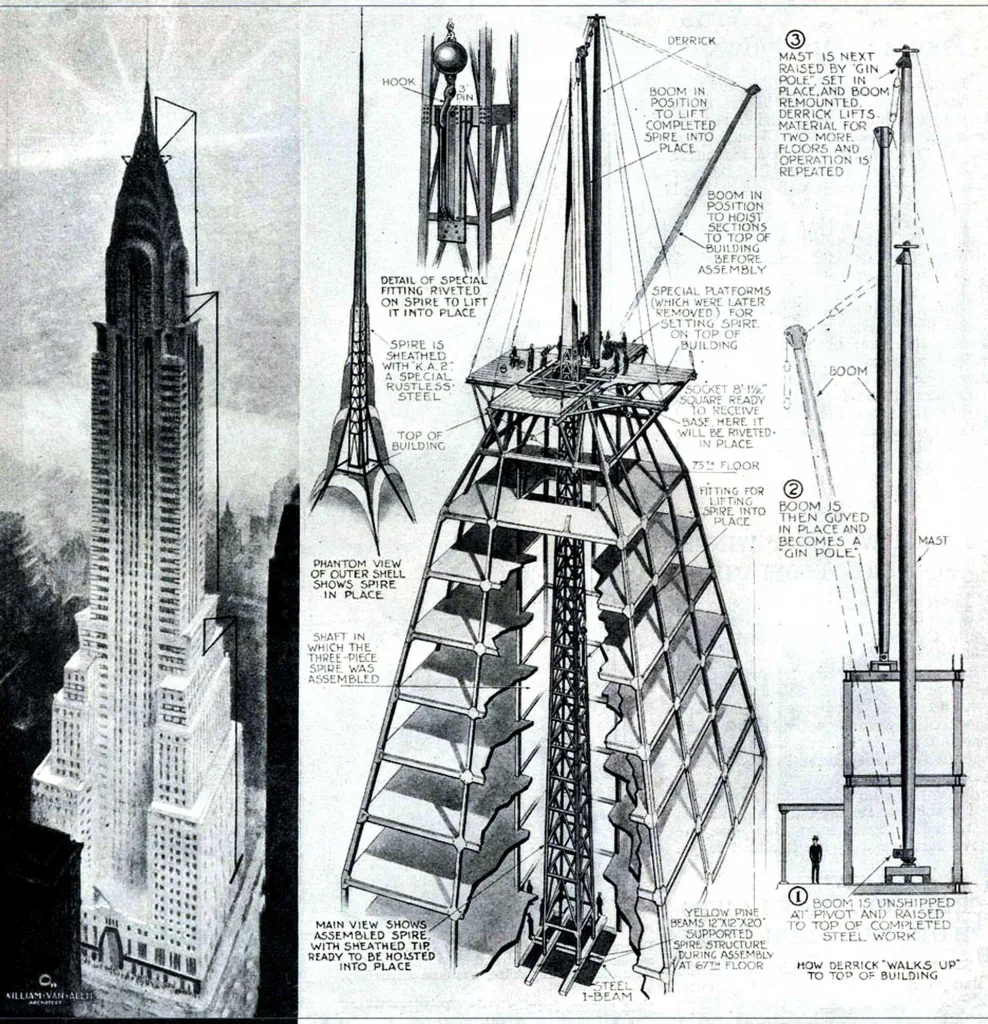

Architectural Competition for the Sky

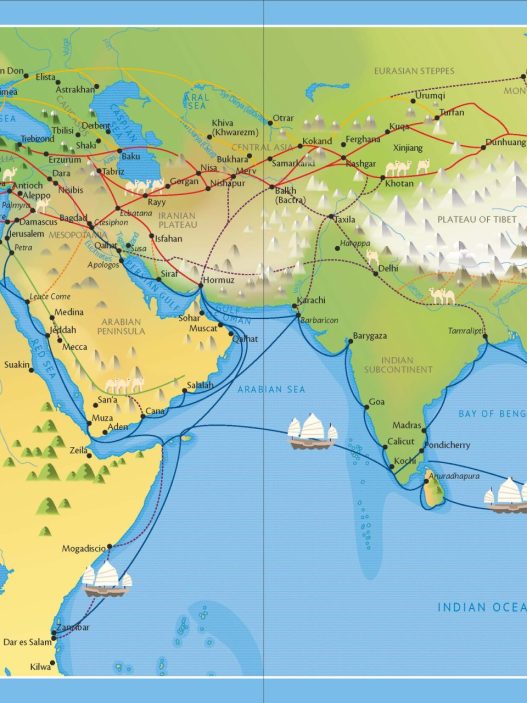

The “race to the sky” predates Dubai. In 1930, the Chrysler Building briefly held the world record before being overshadowed by the Empire State Building. The rivalry between these two turned steel construction into a headline-grabbing sport. These events taught developers that advertising and prestige could be as valuable as rent, while engineers learned to stage construction like choreography. The public learned to read cranes the way sports fans read scoreboards.

By the end of the 20th century, the flag had passed to Asia and the Gulf. The Petronas Towers and Taipei 101 brought the world record eastward, and then the Burj Khalifa completely redefined the scale. The supported core system directs gravity and wind downward through a three-lobed plan that steps back as it climbs, allowing the 828-meter visible slenderness to behave like a single, rigid body in the wind. In a race, this is like the difference between sprinting and pacing; form becomes a strategy to control aerodynamics.

Records aside, the real competition is now qualitative. Super-tall towers compete on how elegantly they meet the street, how little energy they consume per square meter, and how many public moments they contain. While victory was measured in feet in the 1930s, in the 2020s it is measured in experience, adaptability, and life-cycle carbon. This shift is reshaping the “race” from taller to smarter.

Changing Urban Priorities in the 21st Century

Global urban policy is shifting toward compact, mixed-use neighborhoods with rich public transportation options, where daily life is accessible within minutes rather than miles away. Walkability, shade, and clean air are no longer luxuries, but fundamental necessities for human dignity. Reflecting this spirit, the New Urban Agenda calls on cities to design in ways that simultaneously consider social health and climate responsibility. This directive is changing how we evaluate both skyscrapers and the streets around them.

Dubai has begun to incorporate these ideas into its own vocabulary. While the 2040 plan talks about doubling green spaces and recreational areas and increasing resource efficiency, the “20-minute city” initiative is experimenting with placing workplaces, schools, and services within walking, cycling, or public transport distance. In a city dominated by intense heat, human scale is not only about distance but also thermal comfort, shade, and microclimate. Therefore, canopies, arched walkways, and cooled pathways are as strategically important as any silhouette element.

Taken together, this is the paradox embodied by the Burj Khalifa. It is the masterpiece of the structure and image that helped launch a city’s global story, yet it also raises a more difficult question: Can a place obsessed with height be equally obsessed with those who move under the warmth and light at a height of one to three meters above the ground—the feet, strollers, and wheelchairs? The future of being “iconic” will be determined there, on the scale of shadow, breeze, and five-minute tasks.

Design Philosophy and Structural Innovations

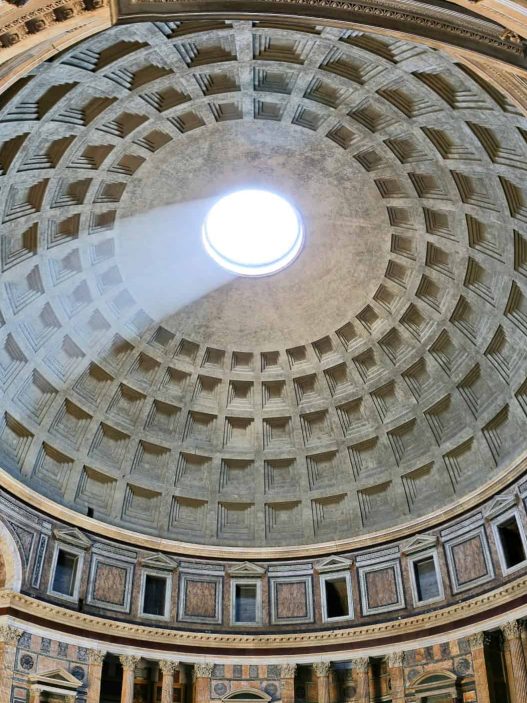

Setting its magnificent appearance aside, Burj Khalifa is an example of a project pushed to the limits of a few simple ideas: the tower’s shape was designed so that the wind would never blow in a regular pattern, three wings support a strong central core, and regional references are combined with challenging engineering. SOM and Adrian Smith did not just aim for height; they adjusted the shape of the building according to the climate, culture, and constructability to give it both a local and aerodynamic appearance.

At this scale, every element must serve multiple functions. The floor plan acts as a stabilizer and a view machine. The facade functions as a heat shield and a beacon. The recesses are like an iconography and a wind trick. The layering of these purposes is the true philosophy behind the world’s tallest building: beauty as the visible remnant of many technical decisions coming together.

Architectural concept designed by Adrian Smith and SOM

Smith’s approach, as he stated, is to read the site, climate, and culture as a single narrative. At Burj, this meant incorporating the desert sun and air into the engineering and transforming local geometries into structure rather than ornamentation. The goal was contextuality on a super-high scale: a tower that performs in extreme conditions while feeling rooted in its location.

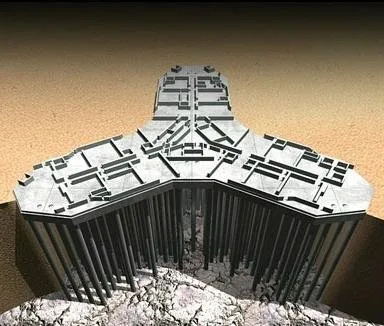

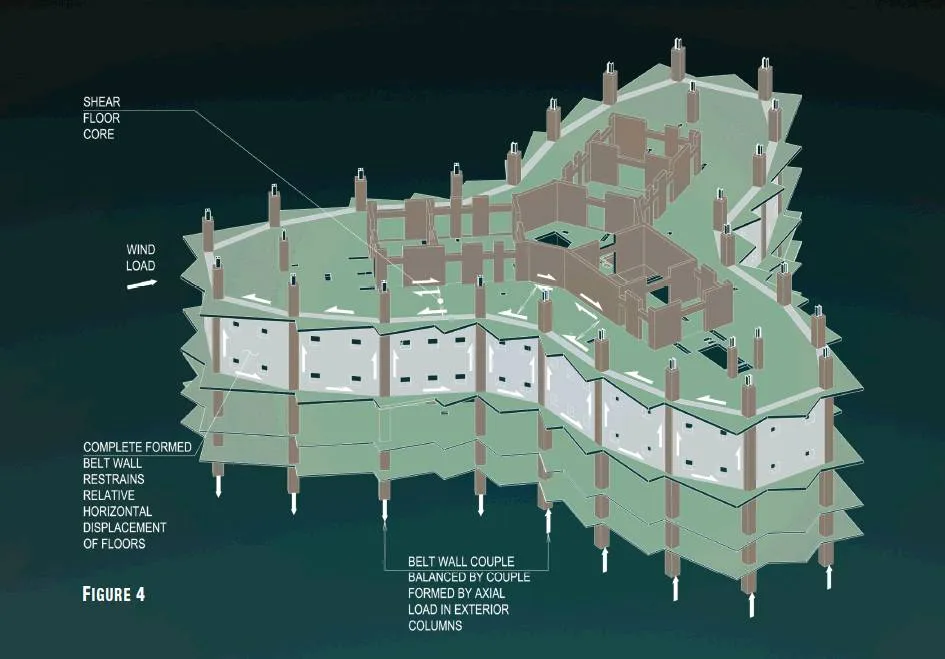

The SOM team framed this intention as a disciplined geometry. A hexagonal core and three wings create a tripod stance with high torsional resistance; the wings support each other, so the building behaves as a single body rather than a stack of separate frames. In other words, the architectural party is the structural system. This clarity makes the tower lighter than its size suggests, simpler to construct, and calmer in the wind.

On the ground, this intention manifests not only in theory but also in practice. Sky lobbies divide long elevator journeys into sky-high neighborhoods; mixed-use elements like hotels, residences, and observation decks are integrated into the Y-plan, supporting rather than obstructing views and daylight. The result is a vertically ascending urban example that remains comprehensible for those who live and work within it.

Inspired by the Hymenocallis Flower

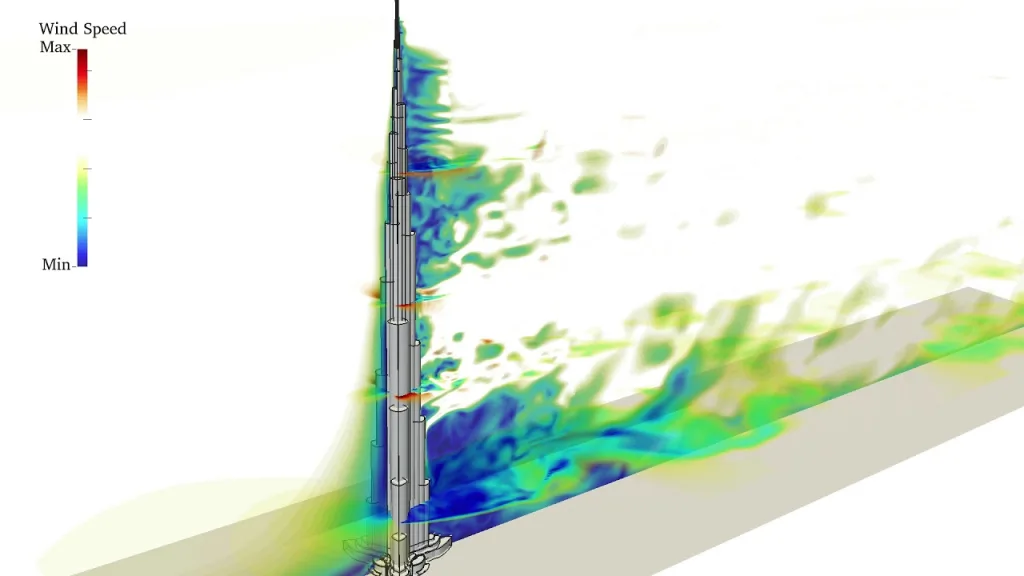

The tower’s three-lobed base was designed inspired by Hymenocallis, a flower species native to the region. This reference is not a metaphor added later, but rather an element that forms the basis of the plan. The three “leaves” diverge from a central point and, as the tower rises, these leaves spiral back, so that while the silhouette remains slender, the way the wind meets the surface constantly changes.

This floral geometry is also compatible with Islamic design traditions—repetition, proportion, and rotation—so that even before understanding the structural logic, the form reads locally in a fluid manner. This is biomimicry with cultural memory; petal-like wings perform practical tasks: they open up scenic corridors to the Gulf, thin floor slabs for residences and hotel rooms, and cleanly direct services along the “petals.”

The landscape reflects the same flower, so the building’s plan and the park’s paths are in harmony with each other. Inspiration organizes everything from the lobby ceiling to the site plan, transforming a poetic starting point into a holistic design language.

Y-Shaped Triplex Floor Plan

The Y-shaped plan is a big idea you could sketch on a napkin. Each wing has its own corridor walls and perimeter columns, and together they support a rigid, hexagonal core. Loads flow smoothly from top to base, and the three-part structure prevents bending, one of the most difficult problems in slender towers. It is elegant because it is understandable: you can see the structure in the silhouette.

These wings do more than just provide support. They keep the floor slabs shallow enough for daylight and views, so this design blends very naturally into homes and hotel rooms. The spirals, which retract one by one, thin the mass as they rise, making the tower appear lighter and allowing the wind to strike it in slightly different ways. Here, spatial quality and stability become one and the same.

The Y plan did not appear suddenly. SOM’s previous work, most directly exemplified by Tower Palace III in Seoul, demonstrated the advantages of this geometry for residential buildings; on the scale of Dubai, it became the key to height. This lineage shows how a floor plan can evolve from a residential strategy to a mega-high structural concept.

Innovations in Wind Resistance and Load Transfer

Wind is Burj’s silent co-designer. SOM and its consultants conducted extensive wind tunnel studies and designed the tower’s shape to “stir up the wind,” thereby breaking the regular vortices that shake tall buildings. Because its stepped, spiral shape is highly effective aerodynamically, the team did not need a tuned mass damper, an unusual achievement at this height.

The tower stands on a platform supported by piles beneath its feet: a 3.7-meter-thick concrete layer connected to deep piles. The system distributes gravitational and wind loads across Dubai’s soil in a redundant manner. Research shows that the platform and piles work by sharing the load rather than placing it on a single element. Vertically, the mechanical/refuge floors and support legs assist in transferring and balancing forces, allowing the core and wings to move as a single unit.

All of this works because the structural concept is fundamentally simple: less load transfer, straight paths to the ground, and a plan that maintains consistency as it narrows. This reminds us that the best wind strategy may not be an additional element, but rather a floor plan.

The Integration of Technology and Aesthetic Form

The facade looks like jewelry, but acts like armor. The composite curtain wall—tens of thousands of reflective glass panels within aluminum frames, stainless steel spandrels, and vertical fins—reduces glare, diffuses heat, and cleans up the building’s lines. The sleek fins you see in the photos also help visually scale the tower and manage wind across its surface.

Inside the core, mobility and climate control are also choreographically arranged. Double-decker Otis elevators transport visitors at approximately 10 m/s and are coordinated by dispatch and tracking systems to make long journeys feel human-scale; sky lobbies redistribute people, so the vertical city feels like a series of zones rather than an endless journey. Meanwhile, engineers have solved the “stack effect” seen in super-tall buildings with pressure zones and controls, so doors don’t slam and comfort remains consistent from the lower to the upper floors.

The cooling system itself has become an integral part of the design. Condensation water from the tower’s air conditioning is collected and reused to irrigate the surrounding park (approximately 15 million gallons per year), creating a cycle between the building and the landscape. Technology is lost within the experience: cooler interiors, shaded walkways, shimmering fins, smooth elevator rides. What you perceive as comfort is actually the result of meticulous engineering decisions.

Importance, Systems, and Sustainability

Concrete, Steel, and Mega-Core System

The tower is primarily composed of concrete at its base and consists of three support wings that share loads with a thick hexagonal core and resist torsion together. The plan, walls, floors, foundation, piles, and steel tower have been fully verified through 3D analysis and adjusted according to gravitational, wind, and seismic behavior. The ultimate height is achieved through structural steel for the tower, but the daily rigidity comes from high-performance reinforced concrete, which functions as a single structure from tip to base.

Below, the building sits on a 3.7-meter-thick foundation connected to deep bored piles; according to research, there are 192 piles with a diameter of 1.5 meters extending to a depth of approximately 47-50 meters beneath the foundation, thus allowing vertical and lateral forces to find alternative paths into the ground. This pile foundation approach distributes enormous loads along the wings of the Y-plan and balances settlement.

The material story also extends upwards: ultra-high-strength mixtures (C80/C60) were pumped to unprecedented heights during construction, breaking the 606-meter vertical pumping record and proving that the megatall era will be defined not only by its form but also by its concrete chemistry and logistics.

Thermal Regulation in Desert Environments

Cooling a glass-made mega tower during hot and humid summer months requires not just a single device, but an entire system. The tower is served by a high-capacity regional cooling facility; according to published figures, it has a cooling capacity of approximately 13,000 tons at peak levels, and intake strategies are used that draw in cleaner, cooler air from above and distribute it through regional systems. The design team also tackled the “chimney effect” seen in super-tall buildings, modeling pressure differences and applying passive and active mitigation methods to ensure that doors, elevators, and comfort remained consistent from the podium to the summit.

Envelope options provide thermal functionality before the chillers start operating. The composite curtain wall uses double glazing and selective coatings to limit solar heat gain. This is a crucial step in Dubai’s climate, as even minor improvements to the facade can lead to significant reductions in building load. Simply put: less heat gain means less energy output.

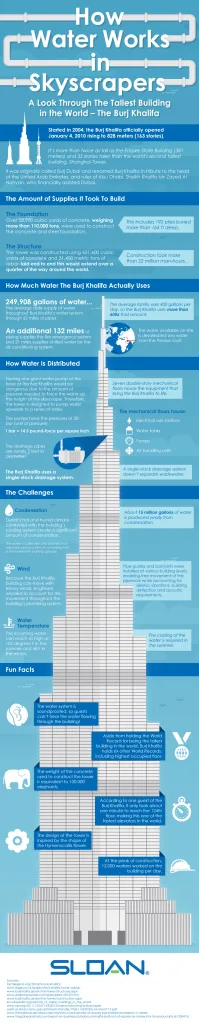

Water Collection and Reuse Systems

The air conditioning system not only removes heat but also dehumidifies the air. Instead of losing the condensate, the tower captures and stores it, then pumps it to irrigate the surrounding park. SOM and the landscape team note that approximately 15 million gallons are recovered annually. Condensate is converted into water rooms that cool shade trees, lawns, and the ground-level experience. Technical summaries indicate that special pipes, storage, and even pre-cooling during the summer months are used to ensure the reliability of this cycle.

https://www.sloan.com/resources/education/infographics/how-water-works-skyscrapers

It is a practical desert ecology: it provides indoor comfort and outdoor greenery, and the systems are sized and detailed so that maintenance crews can run the cycle every day throughout the long cooling season. This is not a complete solution to the regional water stress problem, but it is a rare example of HVAC byproduct becoming part of the landscape infrastructure.

Lighting, Facade, and Energy Efficiency

Upon closer inspection, the skin appears like jewelry—stainless steel fins, sharp edges, mirrored planes—yet each piece serves a climate-related function. Approximately 26-28 thousand pairs of glass panels, framed in aluminum and vertically accentuated with stainless steel fins, manage glare, reflect some of the sun’s energy, and regulate airflow across the surface. Emaar also notes that the glass features an energy-saving silver coating to further reduce heat gain, which is of great importance at this scale.

The building combines passive envelope design with targeted renewable energy sources at the service level. Shortly after its opening, a solar energy system was installed to meet a significant portion of the building’s domestic hot water needs. According to current reports, this system heats approximately 140,000 liters of water per day. This is an elegant way to transform Dubai’s intense sunlight from merely a facade load into a source of benefit. In hot and arid climates, reducing heat gain through windows and switching water heating to solar energy results in a measurable reduction in building energy consumption, as windows and hot water play a significant role in the cooling balance.

LEED Issues and Environmental Criticisms

More than ten years after its completion, the tower’s operations have been audited and certified at the highest level under LEED for Operations + Maintenance v4.1, achieving Platinum certification in February 2024. Facility management partners emphasize that O+M focuses on how a building is operated (energy, water, waste, indoor environmental quality) rather than how it was constructed. Therefore, an existing landmark building can still achieve top-tier performance through retro-commissioning, monitoring, and improved procedures.

This success continues to exist alongside reasonable criticism. Academics and industry groups point out that mega buildings contain high levels of carbon in concrete, steel, and glass, and that “show-off height” or unnecessary towers can add materials that offer very little usable floor space. Others question glass-heavy towers in hot climates and exterior lighting displays that could contribute to light pollution and after-hours energy use, but cities and manufacturers are striving for more responsible facade lighting. In the Gulf region, the carbon cost of drinking water, often obtained through desalination, adds another dimension to irrigation or cooling debates, but new solar-powered RO plants are improving the energy intensity of supply. The picture is mixed: Buildings’ operational gains are real, but the broader environmental balance sheet of megatalls is still being debated and improved.

Human Experience and Scale Discrepancy

Vertical Living and Psychological Distance

High-rise living increases the distance between an individual and the city they belong to. Studies link living in high-rise buildings, especially vertical homes with limited neighborly relationships and scarce daily nature, to higher psychological distress and weaker social bonds. This effect is not inevitable, but it is measurable: Several studies indicate that the risks of loneliness, fear, and stress are higher in high-rise environments compared to mid-rise housing. This is because daily micro-interactions decrease as floors rise.

Design softens this distance by reestablishing contact with living things. Studies show that residents who see trees, the sky, or water from their windows generally enjoy a higher level of well-being than those who see predominantly harsh landscapes. More extensive studies on exposure to nature also yield similar results regarding mood, attention, and stress. In the context of megatall buildings, this makes view quality—that is, how much “real” nature you can see from your home—more than a luxury; it becomes a health variable.

Observation Points, Observation Terraces, and Separation

Observation decks offer a thrill that psychologists sometimes describe as “scenery and sanctuary”: we enjoy observing the world from a safe place. However, the same advantage can turn into a kind of distance—a high, panoramic view that transforms the city into a landscape. Academics working on “vertical city tourism” argue that this bird’s-eye view can be both exciting and strangely disembodying, carrying the risk of replacing the street reality of the metropolis with a curated horizon line through a brief, carefully crafted encounter.

Elevator rides are significant. Elevators subject our vestibular system to rapid changes in acceleration; experiments show that the body records these changes in a way that alters the perception of movement and even time when the doors open. This physiological jolt is one reason why the mountaintop feels “different” from the city below—your senses have shifted gears to get there, and this experience is processed more like a theme park break than an extension of daily life.

The Disappearance of Street-Level Interaction

Cities function best where buildings catch the eye. Decades of urban observation show that transparent, permeable ground floors (with numerous doors, varied uses, and genuine indoor-outdoor contact) provide walking, lingering, and informal security. When super-tall complexes turn their edges into blank walls, deep setbacks, or internalized shopping malls, these ordinary encounters disappear and the street weakens. This loss is not aesthetic; it is social and economic, because the “plinth” is the city’s handshake.

Designers who focus on what pedestrians see at arm’s length—storefronts, thresholds, small gestures of hospitality—consistently report that sidewalks are becoming livelier. Tall buildings are not exempt from this trend; they must do more work at ground level to counter the pull of exclusive lobbies and enclosed retail stores. In practice, this means treating the first two floors not as retail space but as public space, so that the drama of the silhouette does not overshadow the street’s theater.

Scale, Speed, and Sense of Space

Height doesn’t just change the view; it changes time. Geographers use the term “time-space compression” to explain how technology shortens the perceived distance between places. Super-high, high-speed elevators, sky lobbies, and vertical shortcuts compress daily journeys so much that the city begins to feel like a series of non-contiguous islands (lobby, elevator, office, home), connected not by streets but by seconds. This change can be efficient, but it can also thin the city map in one’s mind.

Experimental studies on motion and time perception support the feeling experienced in daily life: Rapid movement through space can distort the perception of how long intervals last. In vertical living, this distortion reinforces the feeling that “up there” is a different world, because speed and controlled movement affect your body clock. Space becomes a series of controlled arrivals rather than a continuous fabric through which you travel.

Alienation and Goals in Super High-Rise Living

It may be tempting to describe megatall living as either alienating or nostalgic, but most residents experience both narratives. On one hand, there are promises: status, quiet, security, light, a rare horizon line. On the other, there are the trade-offs researchers consistently uncover: weaker neighborhood ties, height-induced fears, and the daily friction of shared vertical infrastructure. The literature clearly shows that negative outcomes intensify when towers isolate people from social life and everyday nature.

The opportunity lies here. When designers add real gardens to vertical homes, making them visible and tangible, integrate social spaces into staircases, and open the building’s base to the street like a generous host, psychological distance diminishes. Recent studies in urban mental health show that even brief, regular contact with green spaces can alter mood for hours. In a hot, dense city, this is as much an architectural task as it is a public health one. Tall buildings can be humane, but for that to happen, windows, lobbies, and sidewalks must be designed to human scale.

Cultural, Economic, and Political Importance

National Branding and Architectural Nationalism

Since its opening, the Tower has become part of Dubai’s own story: fast-paced, entrepreneurial, and globally ambitious. Politically, this is part of the Dubai Economic Agenda “D33,” which aims to double the city’s economy by 2033 and position it among the world’s top three cities for living, working, and investing; the skyline is used as a soft power symbol for these goals. In this sense, the building is not just a residential or office building, but a symbol of the economic positioning program.

National branding studies help us understand why height is such an effective message. Academics define skyscrapers as a visual rhetoric that transforms national identity into a communicable brand, serving as concentrated signals of modernity and capacity. In the Gulf region, critics and admirers alike have interpreted the city’s symbols as distinctive elements in a crowded marketplace. The Burj Khalifa has thus become both architectural and argumentative: a claim to leadership expressed through glass, steel, and a meticulously choreographed silhouette.

Tourism, Luxury Real Estate, and Urban Economy

As an economic engine, the tower hosts an area where visitors and retail sales help convert the glamorous image into cash flow. Dubai recorded 18.72 million overnight visitors in 2024, representing a 9% increase year-on-year. The adjacent Dubai Mall recorded 105 million visitors in 2023 and continued to perform strongly in the first half of 2024. These figures demonstrate how this iconic structure increases visitor numbers and spending in the surrounding area. Even Bloomberg’s report on the mall’s expansion considers this investment in terms of attracting high-spending global travelers.

Real estate is following the same pattern. Independent market analyses show that apartments in the tower are trading at a significant premium—approximately AED 3,000 per square meter by the end of 2024, about 78% above the citywide average—confirming the long-observed “icon effect” where brand and address add value beyond mere functionality. At the corporate level, Emaar’s disclosure of information for 2024-2025 details record sales and profits in its Dubai portfolio, highlighting the financial strength of the district model comprising the icon plus shopping center, hotels, and residential properties.

Labor, Construction, and Ethical Debates

In light of these gains, ethical questions arise regarding how such landscapes are created and maintained. Human Rights Watch documented abuses in the UAE construction sector in the 2000s. These abuses included debt bondage, passport confiscation, and unsafe working conditions. This situation makes Dubai’s economic boom a regional example of the exploitation of migrant workers. Subsequent reports continued to highlight the risks faced by workers during the economic downturn of the late 2000s.

The reform is real but incomplete. In recent years, the UAE has taken measures such as wage protection, limiting recruitment fees, and making it easier to change jobs without the employer’s permission. Policy watchers and migration experts characterize these measures as steps away from sponsorship-based control, but implementation shortcomings and exceptions persist. Therefore, there is both progress and unresolved structural issues on the ethical ledger. This is an uncomfortable truth underlying the tower’s brilliance.

Global Impact and Architectural Imitations

Icons travel. The tower’s structural logic, development strategy, and even marketing tone helped write the script for a new “sky race” in the region. The clearest reflection of this is the Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia, designed by the same lead architect and currently under active construction, with a completion target at the end of this decade. Reports from the Financial Times, Architectural Digest, and Reuters clearly define this project as an attempt to surpass Dubai’s record and increase the value of the surrounding land — just as Downtown Dubai did.

Beyond individual projects, academics and journalists coined the term “Dubai-ization” to describe the export of fast-paced, glamour-driven urbanism: the intensive rise of luxury towers and branded districts, sometimes detached from the local context. When used critically or descriptively, this term points to how a specific development language and the image politics behind it have spread globally, with Dubai as the reference point.

Media Representations and Cultural Narratives

Popular media amplifies meaning. When Tom Cruise climbed the facade of the building in Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, this stunt transformed the building’s cultural footprint from record holder to cinema legend. Architectural Digest highlights this move in its research on the tower’s global image. News channels regularly broadcast New Year’s visuals using the tower as a bright backdrop, turning it into a recurring feature of the Dubai brand. These images create a narrative of courage and control (people dancing with the atmosphere) while also softening more complex stories about labor, carbon, or affordability.

Yasser Elsheshtawy gibi kültür eleştirmenleri uzun zamandır bu görsel şölenin iki yüzü olduğunu savunuyorlar: hem kolektif gururun kaynağı hem de sıradan şehri gizleyebilen bir perde. Bu yorumda bina ne kahraman ne de kötü adam, ancak hikayesini okumayı öğrenmemiz gereken güçlü bir hikaye anlatıcısı; yumuşak güç, ticaret, özlem ve tartışmaları tek bir dikey cümlede birleştiren bir hikaye.

Rethinking the Future on a Human Scale

Reassessing the Role of Monumentality

Monuments are still important, but their meaning is shifting from individual objects to systems that improve daily life. Global guidelines now treat streets, parks, public transportation, and public facilities as a city’s true shared monuments, encouraging governments to plan and invest on a human scale so that everyone can participate in urban life. This reorientation is also reflected in the New Urban Agenda and UN-Habitat’s work on public spaces, which treat squares, sidewalks, and small public areas as fundamental infrastructure rather than afterthoughts.

Climate policy is accelerating this reframing. The IPCC’s latest assessment argues that the way cities are planned, built, and renewed will largely determine emission trends; in other words, the most important “monument” a city can build is a low-carbon urban fabric that shortens travel, cools streets, and protects the vulnerable. In this context, grandeur is measured not by height, but by accessibility, shade, and proximity.

Human-Centered Design and Impressive Architecture

Designers have long demonstrated that vibrant and safe spaces emerge from close-up details: front doors opening onto the street, visible and visible windows, and various uses that keep sidewalks active. Jane Jacobs’ “eyes on the street” and Jan Gehl’s decades of public life studies have become practical guides: pay attention to the ground floor, shorten distances, and people will come. When cities incorporate these principles into their policies and projects, public life intensifies without noise and commotion.

Health research now proves this from a physiological perspective. Evidence reviews conducted by the WHO and other organizations show that daily access to green and blue spaces is linked to better mental health, less stress, and better overall health. Therefore, a human-centered approach means designing streets, courtyards, rooftops, and building edges not as decorative elements or rare sights, but as small pieces of nature woven into daily routines.

Alternative Models: Medium-Density and Mixed-Use

Many cities are discovering that they can accommodate more people and reduce car travel without building very tall buildings. Sometimes referred to as the “missing middle,” these mid-rise, mixed-use areas build homes above shops, bring schools and clinics within walking distance, and generate enough pedestrian traffic to support public transportation and local businesses. Contemporary practices show how allowing more neighborhoods to build these home-scale buildings through zoning and regulations increases options and walkability.

Tokyo provides a policy example: national land use regulations permit inclusive mixed-use development across 12 broad zones, helping station areas transform into dense, finely textured neighborhoods rather than isolated clusters of high-rise buildings. Research on metropolitan station areas shows how the diversity of functions around public transport relates to passenger numbers and supports daily proximity, revealing how mid-rise buildings and rail access reinforce each other.

Public sector housing models can carry this structure on a large scale. Vienna’s long-standing program of mid-rise social and subsidized housing keeps rents relatively low while preserving urban vitality by placing most residents in stable, well-located apartments. Official figures and recent reports highlight how consistent investment and design standards have sustained human-scale density throughout this city for over a century.

The Future of Vertical Urbanism in the Climate Crisis

The question is not whether tall buildings are “good” or “bad,” but whether their life-cycle carbon, energy use, and urban integration are compatible with climate physics. The IEA and IPCC emission pathways require sharp declines in building energy intensity and smarter urban forms; research also shows that high-rise offices per square meter generally consume more energy than low-rise offices, particularly in terms of electricity. This reality forces vertical projects to prove their performance in context: connected to the public transport network, shaded by trees in the area, adjusted to lower plug loads, and compared to realistic counterparts.

The amount of carbon emitted throughout the entire life cycle is very important. The guide now requires teams to measure and reduce both structural and operational emissions, and cities like London are demanding official assessments for large projects. The consensus emerging among the industry and advocacy groups is very clear: reusing existing buildings and electrifying them is generally the lowest-carbon option within the relevant timeframe; when new construction is necessary, teams should optimize the structure, identify low-carbon materials, and use on-site renewable energy sources. CTBUH case studies demonstrate meaningful concrete carbon savings through structural optimization, while Architecture 2030’s CARE tool and related research translate the “renovation first” principle into comparable carbon math.

Designing Empathy: Bringing Architecture Back to Earth

A humane future requires that buildings pay as much attention to the nervous system as they do to their programs. Once a niche field, trauma-informed design is becoming mainstream in healthcare, housing, and youth facilities, focusing on legible layouts, light and sound control, and spaces that feel safe without feeling institutional. Initial studies and professional guidance document how these choices reduce stress and support healing, transforming everyday environments into therapeutic tools.

Biophilic strategies deliver measurable benefits. Experiments and field studies show that when workplaces and classrooms are equipped with real plants, landscapes, natural materials, and multi-sensory cues, cognitive abilities improve, stress decreases, and mood improves. This effect is seen at every scale, from small details like a potted plant by the window or the shade of a tree on a bench, to regional designs where parks, water features, and shaded paths transform daily tasks into restorative routines.

Even at the city scale, empathy is interpreted as access to everyday nature. Public health studies show that carefully designed and maintained green and blue spaces within close proximity protect mental health and promote equality. This translates the human-scale agenda into a design summary for the streets themselves: calmer microclimates, short journeys, pocket parks near doorsteps, and ground floors that accommodate the community. This is less about nostalgia theory and more like a practical care architecture.