Modern architecture is undergoing a human-centred revival: the emphasis is on sensory architecture that stimulates all of the human senses.

Traditionally, design has focussed on visual impact. Buildings have often been thought of as photogenic objects rather than lived experiences. But this bias has shown its limits: researchers suggest that neglecting our non-visual senses in buildings may contribute to problems such as noise stress, sick building syndrome and even seasonal depression.

After the COVID-19 pandemic trapped people indoors, the yearning for embodied, meaningful spaces has only increased. We now understand that architecture profoundly affects mental health and wellbeing, comforting or stimulating us in ways we feel as well as see.

In essence, sensory architecture means designing for the five senses (sight, sound, touch, smell, taste) as well as less obvious ones such as proprioception and thermal comfort. By “going beyond the traditional boundaries” of form and function, it creates environments that draw building occupants into a rich tapestry of stimuli. This approach owes much to neuroscience: our brains are constantly integrating sensory inputs, so thoughtful design can regulate light, acoustics, textures and even aromas to shape how a space feels and functions.

As architect StevenHoll observes, “We experience our world and buildings through all our senses and associate them with our entire existential image”. In practice, this means taking into account how a space sounds at noon, how a wall feels at the touch of a hand, the subtle smell when you enter a lobby, or how a floor guides your movement. Tired of sterile, one-dimensional spaces, today’s users are looking for designs that relax, inspire and resonate on a sensory level.

In the following sections, we will explore how architecture activates each sensory field through materials, light, spatial sequencing, acoustics and invisible atmospheres.

Touch and Texture: Materiality as Emotional Language

Our sense of touch is the most intimate way we experience buildings – through the materials we rub against and the textures under our fingertips and feet. In architecture, materials are a form of language that conveys warmth or coldness, roughness or smoothness, even before we physically touch them. The tactile character of a surface profoundly shapes our emotional response: a polished marble floor can feel formal and cold, while worn wooden stairs can feel inviting and familiar. Texture provides a “sensory presence” that anchors us to a space – the weight of a stone wall or the grain of wood activates our memory and sense of time. As Peter Zumthor notes, materials such as stone, brick and wood allow our gaze (and thus our mind) to “penetrate their surfaces” and feel their authenticity and age, while slick modern materials such as glass and metal often “convey nothing of their material essence or age”. In other words, natural materials with rich texture and patina tell a story and invite touch, while uniform synthetic surfaces can feel distant or sterile.

Crucially, we don’t even have to physically touch a material to imagine its texture – tactile perception can be visual. A wall of rough-hewn stone appears rough and earthy, a cue that our brain interprets emotionally. Psychologists point out that even the sight of a fake material (such as plastic “wood” cladding) can trigger a disappointed sensory response. Authenticity and ageing therefore play a role: The subtly worn materials – the polished leather armrest, the patina of copper, the smooth edge of a wooden table polished by the hands of years – instil a sense of comfort and history. “I believe that a good building should be able to absorb the traces of human life,” writes Zumthor, “I think of the patina of age on materials… edges polished by use.” . These traces of time are tactile memories and make a space feel alive and cherished.

Case studies show how materiality is transformed into emotional language. Peter Zumthor’s Therme Vals spa in Switzerland is often associated with the tactility of stone: Zumthor has stacked 60,000 slabs of local quartzite stone to create walls that you can literally feel with your eyes. Swimmers travelling through dim corridors of layered stones feel the hard, cold rock against the warm pool water. Different surfaces are deliberately kept at different temperatures (cold stone, hot water) to increase bodily awareness. This design makes heat and cold a conscious tactile experience, like traditional saunas or Roman baths, what Lisa Heschong calls “thermal pleasure”. In Therme Vals, touch is at the heart of the experience – by running one’s hand over the honed stone, one feels both the material and the sense of geological time, and emerges relaxed and grounded by this contact with nature.

Figure: Layered stone walls in Peter Zumthor’s Therme Vals in Switzerland. The Valser quartzite is left raw and layered, creating a rich tactile experience between rough and smooth, hot and cold surfaces. The architecture stimulates the tactile and thermal senses while visitors “feel” the geology of the mountain on their skin.

Another example is the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, famous for its use of warm, natural surfaces. Visitors often remark that although Louisiana is a large museum, it “feels like home “. Architects Jørgen Bo and Vilhelm Wohlert have achieved this through their choice of materials, which emphasise tactile warmth and subtle ageing. The floors are covered with dark red terracotta tiles or dark Panga Panga wood – a richly coloured wood that has borne millions of footprints since 1958. The wooden floor is not just a surface; it is a silent witness to decades of visitors, gaining small scratches and a shimmering lustre that enriches the ambience. Its quiet darkness provides a calm counterpoint to the bold works of art on display, while its durability withstands the endless rhythm of daily museum life and carries not only footprints but “stories, memories and moments of awe”. The wooden ceilings at the top, whose grain and joinery are visible, give the galleries a tactile warmth and a sense of human touch. Even without touching these elements, visitors can feel the textured bricks, the oiled wood, the “warm, aged surfaces” – details that create a sense of intimacy and comfort. The materials invite you to slow down and feel the space: you can run your hand along a smooth wooden rail or notice the temperature difference as you step from a sun-warmed tiled corridor into a cool brick alcove. In essence, Louisiana’s material palette speaks to the body.

Designing with touch in mind can go beyond public monuments to influence offices, homes and spaces of all kinds. Architects are increasingly using tactile zoning: for example, using rough textured flooring at a threshold to mark a passage, or a cosy rug to encourage lingering in a reading nook. Inclusive design also utilises texture: At a school for the blind in India, architects used different wall textures (ribbed plaster and smooth) to help students orientate and navigate by touch. All these strategies recognise that materiality stimulates emotions. A cold steel bench can discourage prolonged sitting, while a weathered wooden bench feels inviting. Fabrics also play a role – think of the difference between hard vinyl seats and a soft upholstered corner. Texture affectsour mood and behaviour in subtle ways: a gently rounded, polished handrail encourages people to run their hands over it (subconsciously slowing their pace), whereas a sharp-edged metal rail does not invite this caress. Architects thus create an emotional dialogue between person and space by adjusting surface temperature, texture and yield (hardness or softness). In sensory architecture, every choice of material, from a clay brick that absorbs moisture to a metal screen perforated for light, contributes to how a space feels and whether it relaxes us.

Light and Shadow: Orchestration of Vision and Mood

If materials speak to our skin, light speaks to our eyes and soul. Architects have long been choreographers of light and shadow, using lighting to shape mood, focus attention and even tell a spatial story.

Natural light in particular is considered almost sacred in design: Louis Kahn said: “Until the sun hits the side of a building, it never knows how wonderful it is.” By filtering daylight or creating shadow play, architects transform static structures into dynamic environments that change throughout the day. The trick is that light in architecture is not uniform – its direction, intensity, colour and contrast are important. Sunlight piercing a dim chapel can inspire awe, while a soft glow in a library calms the mind. In sensory terms, light is felt as well as seen: bright, high-contrast light can energise or overwhelm; low, warm light tends to soothe. Successful design often requires balancing these extremes and providing transitions for the eyes to adjust to (just as our ears need time to adjust to a quiet room after a loud noise).

A masterclass in light orchestration, Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas is renowned for its beautiful natural lighting. Kahn wanted the galleries to feel as if bathed in a serene, “silver” light, very different from the harsh Texas sun outside. He achieved this with a clever system of cycloid barrel vaults with narrow skylights concealed by aluminium reflectors along their apexes. Daylight comes in and reflects off these curved reflectors, spreading evenly across the concrete vaults. The result is an ethereal, cool illumination, often described as “moonlit ” or “pearlescent”, which gives the art an even clarity. Stepping inside from the bright environment outside, visitors immediately notice the change: the light is softer, almost muted. Kahn has carefully transitioned them to this state – as you approach the museum, you pass through a tree-shaded lawn and a deeply shaded portico, gradually accustoming your eyes from the blinding sun to the gentle interior light. When you enter the galleries, you can appreciate the subtleties of light on works of art without difficulty. This is light as a narrative tool: Kahn is essentially staging a ritual from light to darkness to light – an arrival sequence that enhances the effect of the interior glow. “The harsh Texas sunlight outside is somehow transformed into a cool, silvery ray that bathes concrete, paintings and people, ” writes critic Wendy Lesser: “Everything looks as if it belongs right here.”. At the Kimbell, the light is organised to create a contemplative atmosphere; bright enough to see details, but diffused enough to feel calm without glare. As the day progresses, subtle changes occur – the changing pattern of light in the vault shows the movement of the sun, adding to the sense of the passage of time without ever disturbing the viewer. Kahn has shown that controlling natural light can transform a space from merely functional to transcendent.

Figure: Daylight in Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth, 1972). Hidden skylights bathe the cycloidal concrete vaults in an even, silvery light. Notice how the shadows are soft and the walls are gently lit – Kahn’s design transforms the harsh Texas sun into a calm “moonlit” glow that enhances art viewing.

In sacred architecture, designers often dramatise light to evoke the spiritual. Tadao Ando’s Church of Light in Osaka (1989) is a famous example where a single geometric cut in the wall completely defines the space. Ando’s chapel is a bare concrete box with a sharp cruciform opening behind the altar. At certain hours, sunlight streams through this cruciform cut, projecting a glowing cross of light into the dark interior. The effect is striking: as your eyes get used to the dimness, the brightness of the cross seems almost tangible – light becomes the “material” of the cross instead of wood or glass. Ando deliberately keeps the space simple (grey walls, simple benches) so that natural light enlivens the space and nothing competes with this experience. As the sun moves, the intensity and position of the light cross changes, a constant reminder of the passage of time and, symbolically, of the divine presence. “Light is an important controlling factor in all my works,” Ando notes. “I create enclosed spaces, mostly through thick concrete walls…[detaching it from the outside environment] and natural light is used to bring change to the space.”. In the Church of Light this philosophy emerges as a profound play of light and darkness: the deeper the surrounding shadow, the more sacred and illuminating the light feels. The emotional sequence is reversed of Kimbell’s smooth transition – here one enters directly into gloom, then witnesses the “majestic ” contrast as light cuts through the “deepest darkness”, as Ando puts it. The result is a space that encourages contemplation and awe through minimal means. It demonstrates how directionality and contrast in lighting (a bright focus within darkness) can heighten the sense of drama and significance.

Light can also be playful and experiential. Contemporary artist Olafur Eliasson has built an entire corpus around the immersive effects of coloured light, reflections and fog in space. His famous installation The Weather Project (2003, Tate Modern, London) transformed a vast turbine hall into a hazy indoor sunset: a huge glowing sphere of single-frequency light (looking like an orange sun) was mounted at one end, and the ceiling was covered with mirrors. The combination of golden hazy light and reflections caused visitors to lie on the floor as if on a beach, enjoying an artificial twilight.

By changing the atmosphere of the industrial hall with light alone, Eliasson has shown that people react instinctively to the colour and quality of light. Similarly, his work Your Rainbow Panorama (2011) in Denmark is a circular skywalk of coloured glass that allows visitors to walk through a spectrum of hues and see the city bathed in red, orange, green and blue as they move. Such works emphasise that light in architecture is not static illumination, but a dynamic tool that shapes perception. Different shades can even change our perception of temperature and mood (cold blue versus warm amber lighting).

In everyday architecture, designers apply these lessons by thoughtfully mixing natural and artificial light. Bright, uniform overhead lighting can provide functionality, but contrast and accent bring a room to life – hence interspersed light through skylights, skylights or screens is popular. Transitional lighting is also critical: when moving from a bright lobby to a dim theatre, a foyer can have soft intermediate lighting for the eyes to adjust. Even the simple act of placing a window at the end of a corridor can create a focal point of light that intuitively draws people forward (a form of visual wayfinding through brightness). Lighting in retail or hospitality design is often layered – a combination of ambient lighting for general visibility, task lighting for specific areas and dramatic accent lighting to create mood or emphasise features. The aim is to organise the light as a sequence: perhaps starting bright and energetic at an entrance and becoming softer and more intimate deeper down (as in many spas or restaurants). All these techniques treat light as the primary shaper of experience, not as an afterthought. As Louis Kahn said, “light is the transmitter of all being “, revealing form and space. It can be said that shadow is just as important in sensory architecture, for without shadow or dim spaces, light has no voice. The balance of the two creates nuanced, emotionally resonant environments that engage us visually and viscerally.

Journey and Sequence: Space as Storytelling

Architecture is not just about static walls and roofs; it is fundamentally about movement in space. As we walk through a building or landscape, our senses receive a series of impressions – like scenes in a story. Thoughtful design uses spatial progression, changes in scale, light and sound to shape a journey that elicits emotions such as wonder, surprise, serenity, or even surprise or tension. This concept of spatial storytelling is sometimes called the architectural promenade (coined by Le Corbusier) or simply experience design. It recognises that how we feel in a space often depends on what has happened before and what will happen in the future. A low, dark entrance can feel even more expansive and radiant in contrast to a sun-filled courtyard. A narrow, winding corridor can heighten anticipation before opening into a grand hall. Sensory-wise, the architects choreograph transitions in sensory input – from compressed to open, dark to light, loud to quiet – to create rhythm and drama in the user’s journey.

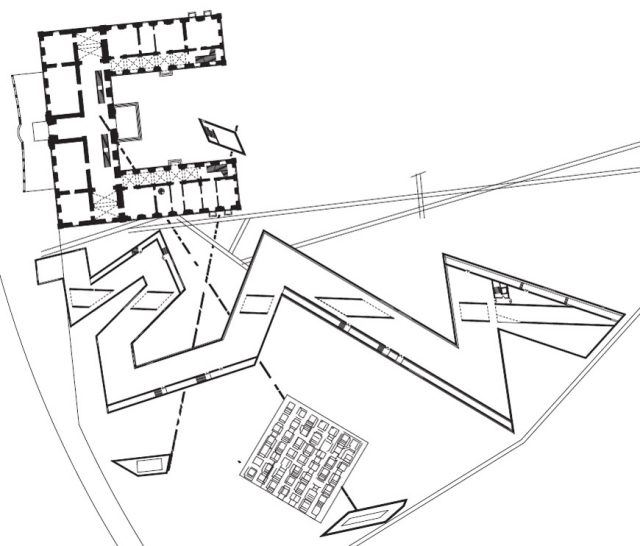

Daniel Libeskind’s design for the Jewish Museum Berlin (opened in 2001) is a powerful example. Libeskind clearly intended the building itself to tell a story of Jewish history in Germany, including the trauma of the Holocaust, through spatial experience rather than words. Visitors descend an underground axis where they have to choose between three intersecting corridors (Axis): one leads to dead-end alleys and an ominous void representing the void left by the Holocaust; another leads to stairs leading to a bright exile garden; the third leads to the main historical exhibitions. The journey is confusing and emotional by design: the corridors slope slightly, the floor is inclined and light is scarce. At one point you enter the Holocaust Void – a long, bare concrete silo, unheated, lit only by a strip of daylight 20 metres above, and eerily silent. The architecture triggers feelings of loss, confusion and reflection through pure spatial means (angled walls, oppressive height, darkness, cold air). Then, turning a corner, you can emerge into the Glass Courtyard, suddenly filled with light and open space – a cathartic release from the earlier claustrophobia. Libeskind wrote a series of scenarios of sensory contrasts to evoke essentially historical emotions: compression and release, darkness and light, confinement and liberation. Visitors often remark that just by moving through these spaces they “feel the history in them “. This is architecture as narrative: the building reveals a story through organised spatial sequences.

Of course, not all journeys are so dark. The High Line in New York offers a more cheerful set of narratives. Built on a former elevated railway, this 1.5-mile linear park takes visitors on an urban journey above the streets. As you stroll, the city itself becomes part of the sensory experience – you hear the distant honking and humming of the traffic below (muted by the elevation and landscaping), feel the breezes directed along the corridor, and see ever-changing vistas: one moment you are under an old warehouse surrounded by steel and vines, the next you emerge into a wide open space with views of the Hudson River. The designers of the High Line (James Corner Field Operations with Diller Scofidio + Renfro) treated it as a series of episodic spaces: there are sun terraces with wooden sun loungers where people take off their shoes and feel the warmth of the boards, sculptural spur paths winding between wildflower gardens (alive with floral scents and insect buzz in summer) and groves of shady trees that create pockets of calm. Each section has its own mood and microclimate. For example, “The Cut-Out” is a section where the concrete deck is transformed into a seating amphitheatre with glass railings, allowing you to sit and watch the street life below as if in a theatre, and hear the city’s soundscape framed in a new way. Further along, seasonal plants create sensory variety – grasses rustling in the autumn winds, bright flowers catching your eye in spring. In essence, High Line choreographs a journey where movement, field of vision and ambient sounds ebb and flow. This is very different from walking on a flat city pavement. The gentle curves and shifting sections arouse curiosity (“What’s round the next bend?”) and provide both lively gathering points and quiet corners. More importantly, the experience changes over time: both over the course of a day (morning solitude versus evening buzz) and across the seasons. Regular visitors often say that each walk along the High Line feels different – a testament to how the design emphasises sequencing and change, keeping the sensory experience fresh and engaging.

Architects use various techniques when designing spatial sequences. One of them is the compression and expansion of space. It’s a classic trick: a dimly lit foyer with low ceilings suddenly opens into a high, sunlit courtyard – the contrast makes the courtyard feel even more impressive and liberating. Frank Lloyd Wright did this at Taliesin West, where, after entering through a narrow, cave-like passageway, you emerge into an expansive desert landscape. Another technique is framed views and “reveals”. Architects can create surprise or focus by controlling what appears as you move. For example, there may be a small window at the end of a long corridor that perfectly frames a tree or a patch of sky – drawing you towards this visual reward. Corners can be choreographed so that a feature gradually emerges as you turn them. Japanese gardens and traditional tea house paths are adept at this: high walls or fences delimit the landscape until, at a carefully chosen point, a beautiful courtyard or mountain vista suddenly appears and increases its impact. Rhythm and tempo are also important: a series of spaces can alternate between open and closed, light and dark, and give a sense of tempo (just as music alternates loud and soft passages). This prevents the journey from feeling monotonous and keeps the senses engaged. The use of thresholds – steps, doors, gateways – likewise prepares us mentally for the change in atmosphere by signalling to the brain that one part of the space ends and another begins.

Architects also take multi-sensory cues into account in turn. Sound transitions are one of them: when moving from a noisy lobby to a quiet library, a good design might include a vestibule with sound-absorbing surfaces or a subtle change in flooring (from hard reverberating stone to soft carpet) to physically signal and affect the quieting. The change in acoustics as you cross the threshold tells your body to lower its voice and your mind to calm down. Changes in heat and air can also determine the sequence – imagine stepping from an air-conditioned museum into a warm, fragrant sculpture garden; the heat and smell hits you and you know you have entered a different realm of experience. This has been used deliberately in many traditional baths and hammams: moving from the hot steam room to the cold plunge pool is both a physical and sensory sequence that invigorates the person bathing.

Designing the journey is about recognising that architecture is a time-based art. We don’t perceive a building all at once; we discover it. The “story” it tells can be as subtle as a serene progression from public to private spaces in a house, or as overt as a series of commemorative spaces evoking historical events. By treating space as experienced over time, architects ensure that each part of a building contributes to a larger emotional arc. A well-constructed spatial journey can give a building a sense of narrative coherence – a beginning, middle and end that our senses can follow and our memory can hold. When you recall the building later, you may not remember every detail, but you will remember how it felt to move through it – the thrill of discovery, the relief of arrival, the moments when you stopped to take it all in. These are the signs of a multi-sensory journey that resonates.

Soundscapes: Design through Acoustics

Although architecture is often called “frozen music”, it also literally shapes the music of our environment – the soundscape of a space. Every building has an aural personality: some spaces are quiet and intimate, some echoing and majestic, some unfortunately cacophonous. Sound in architecture is not a by-product; it can be consciously designed and adjusted through form and materials. In sensory architecture, acoustics is treated as carefully as light or texture because sound profoundly affects comfort, mood and functionality. A restaurant that is too noisy stresses diners; a concert hall that is too dry (no reverberation) kills music; an open-plan office with no sound buffer causes workers to become distracted and tired. In contrast, a well-designed library with soft acoustics can feel like a sanctuary for the mind, and a lively market hall with a pleasant buzz can energise visitors. Sound can even define social space: consider how a quiet zone in a museum invites contemplation, while a bustling lobby encourages conversation.

Materials are the first tools we use to shape sound. Hard, reflective surfaces such as glass, tiles or concrete tend to amplify noise and create reverberation, while soft or irregular surfaces (curtains, carpets, wood panelling, acoustic tiles) absorb or diffuse sound, reducing reverberation. High ceilings and domes can create dramatic reverberation (as in a cathedral where every footstep and whisper is magnified), while low, dense construction can dampen sound. Architects often speak in terms of NRC (Noise Reduction Coefficient) and reverberation times – essentially measuring how “alive” or “dead” a room’s acoustics are. But beyond technical measurements, it depends on the intended atmosphere. A library or meditation room, for example, benefits from a “quiet” acoustic. Louis Kahn’s Phillips Exeter Academy Library(New Hampshire, 1971) achieves this through clever layout and material choices: The outer ring of the library is lined with recessed wooden book stacks (the books themselves are excellent sound absorbers), creating a buffer around the central atrium. The atrium, although high, is lined with concrete and wooden details that diffuse sound. As a result, even when occupied by a large number of students, the space feels enveloped in silence – you can hear a soft footstep or a page being turned, but the sounds do not travel far. Kahn placed great emphasis on “silence and light” in architecture, and here, too, the acoustic design contributes as much as daylight to an atmosphere of studious calm. Visitors often describe Exeter Library as “quiet brilliance ” – the splendour of the space comes with a blanket of silence that encourages focus and introspection. This is no coincidence; it is an architecture that tunes sound to its purpose.

On the other hand, consider a venue designed for music: The Sydney Opera House in Australia. Its iconic sail-like shells house large performance halls designed (and recently redesigned) for rich acoustics. In a concert hall, designers look for a lively reverberation that enhances orchestral music – usually about 2 seconds of reverberation time – so that notes blend together and carry to the back rows. Utzon’s original design for the Opera House Concert Hall featured high vaulted ceilings and curved wooden walls intended to reflect sound evenly. Over the years adjustments have been made: suspended fibreglass acoustic “cloud” reflectors have been added, and more recently a series of petal-like panels and automatic curtains have been installed to fine-tune the hall. These allow the acoustics to be tuned: for a symphony, the curtains retract and the room reverberates richly; for amplified rock, the curtains open to absorb reverberation and prevent blurring. The design recognises sound as a dynamic architectural element. When the renovation was completed in 2022, musicians expressed their amazement that “now you can hear every detail all the way to the back row” and described the improved sound as “a miracle”. Here we see high-tech solutions (steel reflectors, hidden machines) serving a sensory purpose: sonic clarity and versatility. Beyond its visual drama, the Opera House is an example where architecture must perform acoustically to the fullest – the building is as much an instrument as a container for performance.

Controlling sound in everyday environments is equally important for comfort. The rise of open-plan offices and restaurants with harsh industrial décor has taught many a lesson in acoustics. Designers now make sound-absorbing elements an integral part of the design: perforated wooden ceiling panels, felt partition installations with a sculptural look, green walls or indoor plants (which can absorb and diffuse noise), even water features (the gentle gurgle of a fountain can mask unpleasant background noise with a relaxing natural sound). A great example of biophilic sound buffering is Stefano Boeri’s Bosco Verticale(Milan’s “Vertical Forest” apartment towers). These plant-covered high-rise buildings not only green the skyline, but also noticeably reduce urban noise for the building’s inhabitants. Thick vegetation on balconies acts as a sound barrier, absorbing traffic noise and creating a calmer indoor environment. Research has indicated that the leafy facade helps to reduce noise pollution and reinforces how natural elements can be utilised for acoustic comfort. Similarly, the rustle of leaves and the chirping of birds in Bosco Verticale and similar buildings reintroduce pleasant natural sounds that provide relaxation in the city. This shows that shaping the soundscape is not only about blocking out unwanted noise, but also about adding positive sounds. For example, the sound of water is used in many public plazas to mask traffic – our ears tend to prefer the randomness of water over the noise of engines. In hospitals, acoustic design is used to create more relaxing environments (eliminating loud alarms, adding sound-absorbing ceilings to reduce noise, etc.) because research shows that quieter conditions promote healing and reduce stress.

We should also pay attention to how spatial geometry affects sound. Curved ceilings or domes can concentrate sound at focal points (such as the whispering gallery in St Paul’s Cathedral in London, where a quiet word spoken against the wall on one side can be heard clearly 100 feet away on the other side due to the geometry of the dome). Long, parallel corridors can create vibration echoes, while irregular, angled walls (as in many modern auditoriums or studios) disperse sound to avoid such effects. Architects sometimes “tune” a space by adjusting dimensions to avoid hard standing waves – not unlike the way instrument makers tune a guitar body. The everyday equivalent of this: designing a living room so that it doesn’t have an annoying echo when empty – perhaps by adding a bookcase in that spot that reflects sound.

Soundscapes influence whether a space feels public or private, chaotic or calm, expansive or intimate. The majestic echo of a cathedral can instil a sense of awe and scale beyond the visual ( you hear the volume of the space). The warm, muffled sound of a small café with low ceilings and soft surfaces can encourage intimacy, allowing you to lean in and chat quietly. In urban design, the mental health benefits of creating acoustic refuges – quiet pockets such as courtyards or parks sheltered from city noise – by offering a break from constant auditory stimulation are increasingly recognised. Good design finds the right balance: a lively restaurant should have a pleasant background noise (so it feels lively and you have some privacy to talk), but not so much reverberation that you have to shout. An office needs quiet focus areas and other spaces where the collaborative buzz won’t disturb others. By acoustically zoning spaces (through partitions, ceiling treatments, etc.), architects create a sound map that is compatible with a building’s functions.

Designing with the ear in mind is the hallmark of sensory architecture. It transforms idle rooms into spaces that sound right. As one architect put it, “Architecture is a multi-sensory discipline, and the best way to achieve the highest quality of life in our designs is to appeal to all the senses… working with daylight, fresh air[and] supporting physical movement ” – to which we add supporting our aural comfort. A place that sounds pleasant to the ear often feels good, even if we don’t consciously realise why. By shaping soundscapes, architects create an aural backdrop for life that can soothe, inspire or energise us, complementing the multi-sensory experience.

Air, Smell and Thermal Experience: Invisible Atmospheres

Not all sensory design is visible to the eye – some of the most powerful spatial experiences come from invisible atmospheres of air, smell and temperature. We often walk into a room and feel stuffy or spacious, cold or cosy without immediately knowing why. The architects and engineers behind the scenes make design choices about airflow, climate control and even aroma that profoundly affect our comfort and perception. In sensory architecture, these ambient senses are as important as visible surfaces.

Air is the breath of a building. The movement of air – or lack of it – affects comfort, health and alertness. A well-ventilated space with a gentle breeze makes us feel lively and pleasant, while a stagnant room makes us sleepy or restless. Designing for natural ventilation (or passive cooling) has received renewed interest, not only for sustainability, but also for the sensory quality of the air. There is something undeniably pleasant about a gentle cross breeze carrying outdoor freshness, as opposed to the artificial blowing of an air conditioning ventilation. Architects achieve this by directing windows and openings to prevailing winds, drawing air into spaces using open courtyards, high vents or chimney effects. For example, in traditional Arab and Indian architecture, windbreaks and courtyards are used to channel cooling breezes and expel hot air, creating comfortable microclimates prior to mechanical air conditioning. The sensory result of this is that occupants feel connected to the environment: you notice the subtle changes in the wind, the coolness after rain, the daily temperature rhythm.

A contemporary example is Heatherwick Studio’s Maggie’s Centre in Leeds(Yorkshire, United Kingdom, 2020) – a cancer support centre designed with an emphasis on fresh air and natural calm. The building consists of three pavilion-like forms with large operable windows and plant-filled terraces. Its structure is timber and its cladding is porous, which, together with the careful placement of openings, allows the building to “breathe” without dependence on closed mechanical systems. In fact, the design avoids conventional air conditioning altogether. “Natural ventilation avoids the use of mechanical air conditioning systems after selecting the best orientation and arrangement of windows and openings based on a study of site conditions and climate, ” states a description. The result is a centre where the indoor air remains fresh and humidity is naturally regulated by wood and plants – patients and staff often comment on how refreshing and relaxing the atmosphere is, as if you were in an intimate home rather than a clinical facility. This is linked to the concept of biophilia: integrating natural elements (here, natural airflow and abundant greenery) to reduce stress and promote well-being. From a sensory point of view, breathing easily in a space – literally – contributes to an overall feeling of safety and relaxation. Maggie’s Centre demonstrates that invisible environmental engineering (air quality, airflow) is a critical part of human-centred design.

How warm or cold a space feels is closely related to the thermal experience. Temperature can evoke emotion and meaning beyond mere comfort. A warm sunlit corner can feel cosy and inviting on a winter’s day, while a cool stone floor under bare feet provides relaxation on a summer afternoon. Designers can create zones of different temperatures for effect. Think of traditional Japanese houses: they often have an engawa (covered porch) heated by sunlight – a pleasant spot to sit in the cooler months – and also have breezy cross-ventilated interior rooms for humid summers. In her book Thermal Pleasure in Architecture, Lisa Heschong has drawn attention to how architectural spaces have historically celebrated thermal experiences, from Finnish saunas and Turkish baths to Japanese onsen baths. These examples illustrate culturally rich ways of bathing in heat or cold as a shared ritual. A hammam, for example, organises a range from hot steam (which causes one’s skin to flush and pores to open) to a brisk cold wash, all within beautiful vaulted rooms. The design of the bath – domed ceilings with starry openings, marble slabs heated from below – enhances these thermal sensations and also introduces fragrance (usually steamy air infused with the scent of eucalyptus or soap) to create a deeply relaxing, almost otherworldly experience. In modern buildings, although we rarely aim for such extremes, there is a movement in the direction of “thermal zoning “, providing slightly warmer rest areas, cooler active work areas, etc., to get people to gravitate towards what is comfortable for them. Even restaurants sometimes play with this, perhaps keeping a bar area a little cooler (because people are often standing, perhaps dancing), but keeping dining corners a little warmer for comfort when sitting. The important thing is to recognise that a uniform 72°F (23°C) everywhere will not be the most pleasant approach; variety and context are important for thermal comfort.

Now, let’s turn to the often overlooked dimension of spaces: smell. Smell is the sense most directly linked to memory and emotions (the “Proust’s madeleine” effect). A fleeting smell can transport us instantly or affect our mood. “The strongest memory of a place is often its smell,” wrote Pallasmaa; “I cannot remember the appearance of the door of my grandfather’s farmhouse… but I remember especially the smell of the house behind the door, which hit me in the face like an invisible wall.”. Yet in most modern architecture, the goal is odour neutrality – we clean and ventilate buildings to eliminate odours, creating what some critics call the ” anosmic cube“, a structure that looks like a “neutral” art gallery with white walls but smells. However, a growing number of designers are reintroducing deliberate scents as part of the spatial experience. This can be as subtle as carrying a light natural woody scent, such as choosing linseed-oiled wood for a lounge, or using plants and flowers that emit seasonal scents. Some retailers, hotels and even offices use scent diffusers to create a special atmosphere (a practice known as scent branding).

When you enter a Westin hotel, for example, you may notice a special “white tea” scent in the lobby that is intended to signal cleanliness and calm. Although the intention is commercial, it proves how scent can shape our impression of space. Architects of spiritual and cultural spaces have known this for a long time: in churches, temples and mosques, incense is used to express sacredness and stimulate worshippers’ senses beyond sight and sound.

In Kyoto, Japan, one can visit temples or traditional teahouses where kōdō(the art of incense) is appreciated as part of the ritual – the woody smoke curling in shafts of light infuses the tatami-scented air and thus clears one’s mind for meditation. The architecture often adapts to this with small ventilation openings or the way the light filters through to make the smoke visible. In Middle Eastern design, courtyards filled with orange blossoms or jasmine emit aromas in the evening, uniting the indoor and outdoor experience through scent.

Designing for scent in a humane way often means taking advantage of natural cues: the smell of earth after rain (petrichor) can be introduced through courtyards or rain chains celebrating downpours; or the scent of vegetation can be brought into a space by integrating gardens, green walls or potted plants. A famous modern example is the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco (Renzo Piano, 2008), which features a lushly planted roof and open-air courtyards – so that as you walk around you can smell the moist soil and native wildflowers, a deliberate part of the museum/aquarium’s immersive environment that connects visitors to nature. In more utilitarian spaces, ensuring that materials are low odour and providing pathways for fresh air to circulate can prevent the kind of “office smell” that many of us are familiar with.

An important aspect is associative olfactory memory: certain places are defined by an odour that reinforces their identity. Think of a classic library: the smell of old books (volatile organic compounds from ageing paper) is an integral part of this mental image. Or a wooden hut that carries the scent of pine and fireplace smoke – part of its charm is literally in the air. Architects may not always be able to choose a scent, but they can choose materials that smell pleasant (natural wood instead of plastic, leather, etc.) and allow user activities that bring out positive smells (such as real cooking in an open kitchen layout instead of hiding a kitchen – so that the house fills with the aroma of food, an old symbol of comfort).

In sustainable design, passive ventilation and natural air conditioning not only save energy, but also improve the sensory quality of a space. A building that can be opened on a fine day blurs the boundary between inside and outside – you can feel a gentle draft, hear birdsong through the window, smell cut grass outside. These experiences enrich everyday life. Bioclimatic architecture often resorts to vernacular methods: high thermal mass walls that keep the internal temperature constant, shaded verandas for comfortable sitting in hot climates, evaporative cooling courtyards (as seen in traditional Iran and India) where the water from a fountain cools the air and adds a pleasant gurgling sound and humidity – a complete sensory upgrade. One of the exemplary projects is the Eastgate Centre in Zimbabwe, an office building modelled on the passive cooling of termite mounds: it uses large ventilation shafts and heavy walls to draw in cool night air and evacuate hot air, while maintaining comfort with minimal HVAC. Those who work here note not only the comfort but also the natural feel of the air – no harsh air conditioning blowing, just a balanced environment that “breathes ” with the day.

Thermal comfort also intersects with touch: cool materials versus warm materials. Sitting on a stone bench will literally cool you down as it draws heat from your body; in contrast, a wooden bench feels more neutral or warm. This is why saunas are lined with wood (so you can sit on it without getting burnt) but a cooling fountain can be carved from marble. In design, knowing the thermal properties of these materials allows you to create, for example, a warm and cosy alcove (perhaps lined with wood) and a cool alcove (lined with stone) for different preferences. In the same building, some may enjoy a cool terrazzo floor to walk on, others a warm carpet to sink their feet into – providing both in appropriate places can appeal to everyone and enrich the tactile-thermal experience of the space.

As for invisible qualities, we cannot forget humidity and air freshness. Buildings that retain some humidity (not too dry) often feel more comfortable; too dry air (common in overcooled offices) irritates our nose and skin. Using indoor plants, water features or not over-sealing the building can help to achieve this balance. And of course, ensuring air quality – the absence of toxic fumes, adequate filtration or natural exchange – literally affects our health and cognitive functions. Sensory architecture goes hand in hand with wellness design: the air should be as inviting as the visuals.

In a nutshell, paying attention to air, smell and temperature transforms a building from a lifeless box into an enveloping atmosphere. These factors are often what make a space truly comfortable or memorable, even if we only recognise them subconsciously. The best architecture, as Zumthor puts it, can “assimilate the traces of human life” and respond sensitively to them – and this includes the breath, warmth and scent of life. When architects create invisible layers – the soft drift of air, the bouquet of materials and environment, the thermal touch – they create spaces that breathe and embrace all human senses.

Design for the Full Human Experience

At its highest point, architecture addresses the whole person – body, mind and soul. As we have discovered, designing with the senses in mind leads to environments that are not only seen , but felt, heard and remembered in all their dimensions. This multi-sensory approach is more than a stylistic trend; it is a return to a fundamental human-centred design that recognises that we perceive space with our entire nervous system. For many, the future of architecture will be defined less by radical visual forms and more by the quality of the experience a space offers – how it promotes wellbeing, stimulates emotions and creates meaning through all the senses.

Sensory design is also a path towards inclusivity and “sensory equality”. Spaces that engage multiple senses tend to be more accessible to a wider range of people. For example, a person with low vision may navigate better if a building has tactile floor cues and rich acoustic feedback (as seen in schools for the blind with textured pathways). An autistic person who may be overwhelmed by certain stimuli may find comfort in spaces designed with controlled acoustics and soft lighting transitions. Older adults who may have diminished senses benefit from environmental design that can be read with multiple senses at once – bold visual contrast plus clear acoustics plus distinctive odours can compensate for sensory loss and trigger memory. Designing for all ages and neurotypes means considering sensory needs: perhaps a library might include a softly lit, sound-reduced reading room for those needing calm, while offering a sunny, airy lounge for others – one size does not fit all, but a spectrum of sensory environments can. As one architect has noted, “the world is in desperate need of spiritual and meaningful spaces that balance intellectual creativity with a humanistic affinity for the material and tactile.” In other words, after decades of sometimes overly cerebral or purely pragmatic design, we yearn for spaces with soul – and soul comes from interacting with our human senses and emotions.

Designing multisensory spaces is not about adding complexity for its own sake; it is about intentionality and authenticity. It requires architects to think like composers or choreographers of atmospheres. It is the overall mood that resonates, as Peter Zumthor describes in his concept of “atmospheres “: “We perceive atmospheres through our emotional sensitivity… in a fraction of a second we have this feeling about a place.” This feeling arises because all sensory inputs synergise simultaneously. Successful design translates these inputs into a coherent feeling of peace, vibrancy, respect or enjoyment. When all the elements – sight, sound, touch, air – are in harmony, the atmosphere is palpable and powerful. As Zumthor says, it “sticks to your memory and emotions “. Think of the spaces you cherish most: you can probably remember the light falling into your favourite room, the creak of the floorboards, the smell of summer coming through the window. Our favourite architecture sets the stage for life’s moments precisely because it stimulates our senses and provides a rich backdrop for our memory.

In practical terms, the movement towards sensory architecture is influencing education and professional practice. There are calls for architects to develop “sensory toolkits ” – checklists or design guidelines that enable projects to thoughtfully address each sense at every stage (from site planning – taking into account noise and wind patterns – to material selection to lighting design). Some forward-thinking firms are literally mapping sensory experiences on drawings: sensory diagrams showing where quiet and intense sound, hot and cold zones, key sight lines or touch points should be. The Academy bridges neuroscience and architecture through research into how different brain types (neurotypical, neurodegenerative) respond to environmental stimuli. This emerging field of neuro-architecture uses scientific insight to validate design decisions that intuitively feel right – for example, confirming that access to nature sounds reduces stress hormones, or that certain light spectra support circadian rhythms and better sleep for hospital patients. Design brands and building standards (such as WELL certification) now explicitly include sensory criteria such as acoustic comfort, biophilic elements (for visual and olfactory connection with nature), thermal and olfactory comfort as measures of a building’s quality.

What does all this mean for the architect or designer? It means expanding one’s palette. It means not just looking at renderings during design reviews, but asking: How will it feel to walk here? Will there be a slight sound or echo? How will the material smell when the sun warms it? Can a blindfolded person still appreciate this space through touch and hearing? By asking these questions, we push designs away from two-dimensional aesthetics towards full sensory immersion. This doesn’t necessarily cost more; it’s often about thoughtful choices and sometimes about restraint (e.g. letting a breeze in rather than closing a window). It may even mean collaborating with others (acoustic engineers, lighting designers, landscape architects (for scents and plant textures)) early in the concept phase so that all sensory aspects are developed holistically.

The ultimate goal is environments that nourish the human spirit. In an age of increasingly pervasive digital experiences and virtual reality, the tactile, tangible reality of architecture offers something irreplaceable. As architect Kengo Kuma observes, there was a time when we treated architecture as a visual media spectacle, but “people are returning to the real life of the five senses. Architects will be expected to design for these senses.” Indeed, after being isolated behind screens, people desire real spaces where they can hear the murmur of the crowd, feel the air, smell the trees, touch the rough bricks. It is precisely this embodied presence that is the gift of architecture – as Daniel Libeskind passionately puts it ” we are not just minds, we are bodies… we are embodied; it is a visceral experience ” and reminds us that buildings should activate not only our minds, but our flesh and blood as well.

Designing with the senses means designing for life. It’s about creating spaces that reflect the richness of the natural world and the diversity of human perception. Such spaces tend to be more memorable, more loved, and often more sustainable (because what is sustainable if not a design that people value and care about over time?) A multi-sensory design approach encourages architecture to slow down and adapt: the glint of the afternoon sun on a wall, the sound of rain on a skylight, the scent of jasmine near an entrance, the cool stone inviting a hand – these details can be as important as the grand form. As we build the future, let us not forget that the built environment is ultimately a stage for human experiences. By engaging all the senses, we enrich those experiences and reconnect architecture with what it means to be fully, sensually alive in a place. In doing so, we create architecture that not only looks good, but feels right – architecture of the full human experience, where design and life are seamlessly intertwined.