Urban property is more than legal deeds and property titles – it is written into skyscrapers, streets, and neighborhoods. Every spatial decision, from the height of a skyscraper in the city center to the width of a sidewalk, encodes power: who shapes the city’s image, who moves freely in its spaces, who builds and who is displaced, whose voice is included in the design, and whose future is prioritized. In this research-informed analysis, we address five critical questions that frame urban property not only in legal or political terms, but also through the architectural and spatial mechanisms that define power, access, and belonging in the built environment. Each chapter explores a theme ranging from the impact behind iconic silhouettes to the fight for mobility justice, from gentrification forces to the promise of participatory design, and from surveillance and climate change to the contested future of cities. By analyzing case studies from around the world and drawing on urban theory, we seek to understand who the city truly belongs to and how design can challenge or reinforce this ownership.

Whose Vision Shapes the Silhouette?

When we look at a city skyline, we usually see the ambitions of developers, the decisions of planners, and the flow of capital etched into steel and glass. But whose vision is truly shaping these silhouettes? In most cases, it is a complex interplay of private developers’ profit-driven goals, political actors’ planning decisions, and underlying economic forces that determine what gets built where. Zoning laws and building codes play a crucial role: for example, New York City’s zoning regulations have long determined building height, density, and shape—literally shaping the Manhattan skyline. Tools such as Floor Area Ratio (FAR) limits and height restrictions set by planners constrain form, but developers find creative ways to bend these rules. In New York, developers routinely merge zoning parcels and purchase air rights to exceed normal boundaries, merge parcels, or finance transit improvements to earn bonuses that allow taller buildings. As one zoning expert noted, “FAR may seem like a static number, but unlocking additional floor area in Manhattan is not straightforward… Every merger, bonus, or waiver comes with its own ripple effects.” In other words, the skyline is often a direct product of regulatory chess games and incentive structures.

However, beyond regulations, the influence of capital lies at the heart of the matter. In an era of iconic architecture and global investment, tall buildings are often perceived first as assets and then as architecture. Global cities like London, New York, and Dubai have commodified their skyscrapers, viewing their iconic buildings as the “sky-high vaults” of transnational capital. Consider New York’s “Billionaires’ Row,” where ultra-thin luxury towers rise above Central Park. Many units in these skyscrapers remain vacant because they were purchased by wealthy investors as holding properties rather than homes. “The owner has never been there—it’s an investment. It’s an asset,” It’s like owning a Picasso,” explains the real estate agent for a penthouse worth $169 million. In fact, this new type of super-high-rise apartment has created a “completely new luxury real estate asset class” fueled by the massive increase in global wealth concentrated among a small elite. The result is architecture clearly shaped by finance: sleek towers optimized for less daily living and more liquidity, designed to minimize maintenance and maximize exchange value. As Professor Matthew Soules observes, “financial capitalism is turning buildings into more shares, more cash,” and transforming architecture into nothing more than an investment vehicle. According to this view, the skyline follows the adage “form follows finance”—the tallest buildings rise where they can generate the highest returns.

The ultra-slim skyscrapers on Manhattan’s “Billionaires’ Row” reflect the power of private developers and global capital. Many of these towers were made possible by the purchase of air rights and the use of zoning incentives, highlighting how financial power and regulatory maneuvers shape the skyline.

Meanwhile, public interest and civic vision often struggle to have a similar impact on the horizon. Although city governments impose design standards and occasionally demand public benefits (such as transit improvements or affordable units in exchange for extra height), the dominant mode in many global cities has been speculative development rather than architecture in the public interest. The commodification of skyscrapers is clearly evident in London, where the explosion of towering structures with nicknames (“Gherkin,” “Shard,” “Cheesegrater”) in the 2000s significantly altered the cityscape. These projects were largely supported by international investors. Since 2010, over 64% of large office investments in London have come from overseas buyers. For example, The Shard was built with Qatari funding and opened with many floors empty—essentially a bet on future value, feasible only because deep-pocketed backers could afford to wait. Such developments raise questions: Whose needs are they serving? Skyscrapers financed as assets typically cater to a global elite or corporate tenants and offer limited benefits to average city dwellers. In contrast, public interest design prioritizes affordable housing, human-scale amenities, or socially inclusive landmark structures—but these rarely dominate the skyline without strong political will or public pressure. This contrast can be seen in debates over projects like New York’s Hudson Yards (a shiny private mega-project criticized for its lack of affordability) versus civic projects like libraries, museums, or public housing that rarely reach monumental heights. In short, a city’s vertical profile is typically the result of bargaining power: developers bring capital and bold proposals; planners and politicians set the rules (and sometimes bend them for the right price); and architects work within these parameters and often serve the interests of those who commission them. The skyline responds not only to those who can finance it, but also to those who surround it. Therefore, whether a city’s tallest tower is a structure that serves the public good or a machine that maximizes profit is a question of whose vision was given authority in the development process. As long as speculative real estate capital and development-oriented policies prevail, skyscrapers will likely continue to reflect the priorities of wealth and political influence more than the pure public good.

Who has the right to move freely in the city?

The physical ownership of a city may be on paper, belonging to homeowners and governments, but ownership is also felt in terms of who can easily or honorably access the urban space and move around in it. This question addresses issues of mobility, infrastructure, and exclusion: highways and transit lines that connect some communities while cutting off others; public spaces that embrace everyone versus privatized or policed spaces that effectively exclude certain groups. The right to move freely is fundamental to urban life—but history shows that not everyone has been able to enjoy this right equally.

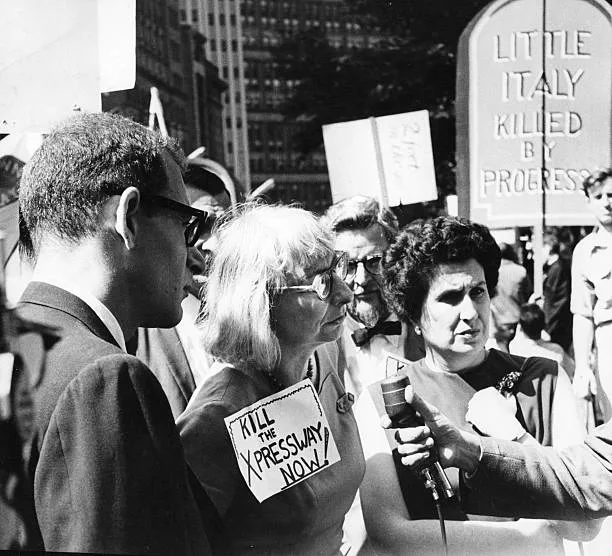

One striking example of this comes from urban planning in the United States in the mid-20th century, when highway construction often passed through minority and low-income neighborhoods. Robert Moses, the powerful urban planner in New York, was notorious for directing highways in ways that would eliminate or divide working-class communities, and this approach spread to cities across the country. Such projects were ostensibly about moving cars efficiently, but they privileged suburban vehicles over city residents and effectively walled off or uprooted neighborhoods predominantly inhabited by people of color. In New York, Moses’s proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway in the 1960s would have destroyed parts of Greenwich Village, SoHo, and Little Italy had it not been for the fierce resistance led by activist Jane Jacobs. Jacobs argued that streets are not just for cars but for people, and that walkable, human-scale neighborhoods are the lifeblood of cities. Her victory over Moses’ highway plan (she and neighborhood residents organized rallies, protests, and even got arrested to stop it) became legendary: David defeating Goliath to defend community access and pedestrian life. The broader principle was that the top-down imposition of car-centric infrastructure could completely strip local residents of their right to their own city. Highways like Moses’ were often elevated or sunken barriers, cutting up street grids and “darkening” the pedestrian landscape. They worsened air quality and lowered property values along their routes, reinforcing segregation—so much so that some called inner-city highways a “physical form of American apartheid.” Indeed, federal policies and planners in the 1950s and 1960s deliberately targeted “blighted” (often minority-populated) neighborhoods for highway routes; this legacy is now being reevaluated as an injustice. When the fragmentation and isolation of certain communities in the name of progress was deemed acceptable, the right to move freely was violated.

Jane Jacobs (center, holding a “Kill the X-Pressway Now” sign) at a protest against the Lower Manhattan Expressway in 1962. Activists successfully stopped this 10-lane highway project, defending community rights against car-centric development. Jacobs’s battle with planner Robert Moses became a symbol of the fight for pedestrian-friendly, human-scale urban planning against top-down, car-centric plans.

Even today, invisible walls restrict mobility for many people. Consider the phenomenon of gated communities and specially controlled areas. From American suburbs to Latin American cities, walled communities have proliferated around the world—literally fortified enclaves. These “settlements restricted by physical barriers such as walls, fences, and controlled entry points” promise security and seclusion to their residents. But the flip side is social segregation. Gates and guards send a signal about who is welcome and who is not. Critics argue that this “fortress mentality” contributes to social divisions and a false sense of security while undermining social cohesion. But not all barriers are physical walls. Sometimes ownership of space is imposed through more subtle means, which we might call “barrier urbanism” or hostile design. For example, privately owned public spaces (POPS) such as corporate plazas or shopping malls are ostensibly open to the public, but are often patrolled by security and contain rules that prevent protest, loitering, and even the gathering of certain types of people (e.g., homeless people or young people). The result is a patchwork city where some can move freely, while others are unwelcome or actively monitored. Sociologist Setha Low has documented how some high-level “public” spaces create exclusion through design and management—a kind of “invisible wall” discomfort or intimidation for those who don’t fit the expected demographic. Similarly, seemingly harmless urban design choices, such as the placement of benches, transit stations, or pedestrian crossings, can connect or separate neighborhoods. A pedestrian bridge or an accessible transit stop can overcome a barrier like a highway or a river; conversely, the absence of safe crossings can turn a four-lane road into a psychological barrier as impenetrable as a fence.

Mobility justice also encompasses transportation equity: whether all city residents can travel with comparable ease. Here, sharp inequalities emerge along lines of class, race, and ability. More affluent neighborhoods typically have better transportation options (or the luxury of owning a car), while low-income residents face longer, more difficult journeys. Research in US cities shows that high-income (typically white) residents tend to have greater access to public transportation and also own cars at higher rates—giving them a double advantage in accessing employment. Meanwhile, low-income and minority workers disproportionately rely on transportation and often work irregular hours when transportation services are inadequate. The Urban Institute reports that workers who work late shifts and must use transit have commute times that are, on average, twice as long as those with access to a car. For many, there is no “safe or economical way” to get to work during off-peak hours. In practical terms, a nurse finishing a midnight shift or a dishwasher working in a hotel before dawn may wait an hour for a 90-minute bus ride, while a wealthier colleague with a car can get home in 20 minutes. These inequalities translate into time loss, income loss, and often dangerous journeys (e.g., walking through unsafe areas due to infrequent buses). The concept of spatial justice argues that such inequalities are not merely inconveniences but violations of a fundamental urban right. Geographer Edward Soja wrote that “there is a geography of justice, and the equitable distribution of resources, services, and access is a basic human right.” Access to mobility—the freedom to move safely and comfortably within a city—is one such resource. When certain groups (the poor, people of color, people with disabilities, the elderly) are effectively trapped due to inadequate transportation or unsafe streets, this reflects a broader social inequality as a spatial injustice. The difference between a warm, walkable street and a restrictive highway, between a frequent transit line and a “transit desert,” is the difference between being an empowered city citizen and a second-class citizen. Therefore, the right to move freely is a litmus test for urban property: a truly inclusive city is one where everyone, regardless of their background, can navigate public spaces without fear or unnecessary hardship. To achieve this, it may be necessary to remove some real barriers (such as the divisive highways that some cities are considering removing) and invest in transit and pedestrian infrastructure in underserved areas—essentially, reconnecting communities that are physically or socially walled off from one another.

Who Will Build, Who Will Be Pushed Out?

Cities are always changing—old buildings are demolished or renovated, new developments rise—but the politics of who gets to build and who gets displaced has become one of the most contentious urban issues of our time. Gentrification, redevelopment, and land value inflation can transform neighborhoods seemingly overnight and raise the question: development for whom? Often, investment patterns reveal that when new wealthy residents “build up” or “improve” an area, long-time low-income residents are “pushed out”. Here, we examine how architectural changes serve as signals (and intermediaries) of gentrification, how past policies such as urban renewal and redlining have paved the way for today’s displacement, and how marginalized groups are claiming their right to build through informal or grassroots architectural means.

When you walk through a neighborhood that has suddenly “gone upmarket,” you may notice the encoded signs of gentrification in the built environment. Bright new cafes and boutique shops, bike lanes and street trees, facades renovated with minimalist design—these cosmetic improvements often precede (or accompany) the influx of wealthier residents. As urban sociologist Sharon Zukin observes, “Since the 1970s, certain types of luxury restaurants, cafes, and stores have emerged as highly visible signs of gentrification in cities around the world.” These trendy businesses not only cater to more affluent tastes, but also contribute to a new narrative about the neighborhood being cool or safe, thereby encouraging more real estate speculation. The visual contrast can be striking: the “dive bars” and pawn shops of early gentrification have given way to craft coffee shops, yoga studios, and organic markets, but the effect is similar—they “embody the neighborhood’s narrative of change” and often indirectly exclude or alienate previous residents. For example, the emergence of a gourmet grocery store or a craft brewery in the place of a former discount store or working-class bar signals a shift in the class appeal of the neighborhood. These changes in the commercial landscape go hand in hand with architectural changes: old apartment buildings or row houses are renovated, warehouses are converted into loft apartments, and new glass apartment buildings sprout up on formerly vacant lots. In some cases, cities or developers are installing amenities like bike-sharing stations, pocket parks, or improved lighting—seemingly for everyone, but often benefiting newcomers. In a recent study at Stanford, artificial intelligence was even used to scan Google Street View images and identify such “visual cues of gentrification”—like renovated building facades or trendy storefronts—and these were indeed linked to demographic changes. When these physical changes occur, rents and home prices may have already risen far beyond what long-time residents can afford. In fact, architecture and design act as both a harbinger and a driving force of displacement: the more attractive a street appears, the more profit opportunities real estate investors perceive, and they often “revitalize” the area in a way that prices out the original community.

Aerial view of sharp spatial inequality: the Rocinha favela in Rio de Janeiro (below) borders directly on the affluent São Conrado/Leblon neighborhoods (above). Swimming pools and tennis courts adorn the lush, high-income area above, while self-built informal dwellings are densely packed on the hillside. Such juxtapositions historically reveal who has the “right to build” (the poor who built favelas out of necessity) and who benefits from urban land values (the wealthy who enjoy the amenities nearby). This contrast also foreshadows gentrification pressures as higher ground becomes more valuable.

The process of who built and who was displaced has deep historical roots. Redlining and urban renewal in the mid-20th century in the US paved the way for later gentrification. Redlining was a discriminatory policy where banks and federal programs marked minority neighborhoods as “unsafe” for investment on maps, using red lines; this meant that residents (often Black) couldn’t get mortgages for home repairs or purchases. Decades of disinvestment led to the deterioration of the housing stock and stagnation of property values in these communities. Then, in the 1950s and 1960s, urban renewal programs—sometimes criticized as “Black removal” because they targeted “blighted” areas (often the same neighborhoods marked by red lines) for demolition to make way for highways, government buildings, or modernist towers—were implemented. The legacy was devastating: as one observer noted, “Refusing to invest led to the decay of communities and their subsequent eradication through urban renewal.” Hundreds of thousands of families—the overwhelming majority Black and poor—were displaced during this period. When we talk about gentrification today, we are often following the paths laid out by these earlier traumas. Neighborhoods that were once red-lined and starved of capital are now suddenly attractive to investors (because of their central locations or historic building stock). Ironically, having been undervalued for so long, they have become “ripe” for reinvestment and redevelopment—but the investments are flowing not to long-time residents (most of whom are renters and do not own property that will appreciate in value), but to outside developers and new property owners. For example, in cities like New York, areas targeted for renewal or neglected in Harlem or the Lower East Side are rapidly gentrifying, raising the painful possibility that the grandchildren of those displaced by the 1960s bulldozers could now be pushed out again by rising rents and apartment conversions. Meanwhile, in Paris, the legacy of low-income (often immigrant) communities being pushed to the city’s periphery—the banlieues—during the post-war housing boom has created a lasting spatial divide. High-rise suburbs were built to house workers and immigrants outside the city center, effectively segregating them. As one analysis put it, “low-income households were pushed out of their neighborhoods, beyond the city limits, creating segregated areas… This gentrification process [after World War II] initiated a polarization between the city center and the suburban population.” Today, Paris’s affluent core is surrounded by poorer suburbs whose residents generally feel they have never “owned” the city—they are, in a sense, outsiders looking in. Their exclusion has even been defined as a violation of “urban rights.” And when urban redevelopment occurs in these peripheral areas, it can similarly displace or disrupt established communities (e.g., the demolition of aging housing stock or the “eco-renewal” of neighborhoods that subsequently attract higher-income tenants).The process of who built and who was displaced has deep historical roots. Redlining and urban renewal in the mid-20th century in the US paved the way for later gentrification. Redlining was a discriminatory policy where banks and federal programs marked minority neighborhoods as “unsafe” for investment on maps, using red lines; this meant that residents (often Black) couldn’t get mortgages for home repairs or purchases. Decades of disinvestment led to the deterioration of the housing stock and stagnation of property values in these communities. Then, in the 1950s and 1960s, urban renewal programs—sometimes criticized as “Black removal” because they targeted “blighted” areas (often the same neighborhoods marked by red lines) for demolition to make way for highways, government buildings, or modernist towers—were implemented. The legacy was devastating: as one observer noted, “Refusing to invest led to the decay of communities and their subsequent eradication through urban renewal.” Hundreds of thousands of families—the overwhelming majority Black and poor—were displaced during this period. When we talk about gentrification today, we are often following the paths laid out by these earlier traumas. Neighborhoods that were once red-lined and starved of capital are now suddenly attractive to investors (because of their central locations or historic building stock). Ironically, having been undervalued for so long, they have become “ripe” for reinvestment and redevelopment—but the investments are flowing not to long-time residents (most of whom are renters and do not own property that will appreciate in value), but to outside developers and new property owners. For example, in cities like New York, areas targeted for renewal or neglected in Harlem or the Lower East Side are rapidly gentrifying, raising the painful possibility that the grandchildren of those displaced by the 1960s bulldozers could now be pushed out again by rising rents and apartment conversions. Meanwhile, in Paris, the legacy of low-income (often immigrant) communities being pushed to the city’s periphery—the banlieues—during the post-war housing boom has created a lasting spatial divide. High-rise suburbs were built to house workers and immigrants outside the city center, effectively segregating them. As one analysis put it, “low-income households were pushed out of their neighborhoods, beyond the city limits, creating segregated areas… This gentrification process [after World War II] initiated a polarization between the city center and the suburban population.” Today, Paris’s affluent core is surrounded by poorer suburbs whose residents generally feel they have never “owned” the city—they are, in a sense, outsiders looking in. Their exclusion has even been defined as a violation of “urban rights.” And when urban redevelopment occurs in these peripheral areas, it can similarly displace or disrupt established communities (e.g., the demolition of aging housing stock or the “eco-renewal” of neighborhoods that subsequently attract higher-income tenants).

Nevertheless, in the midst of these top-down forces, marginalized groups have consistently defended their right to build in the city, often through informal or grassroots architecture. In many developing world cities where official housing is inaccessible to the poor, large informal settlements such as shantytowns, favelas, and shanty towns (shanty towns in Turkey) have emerged. In such cases, who can build housing? Answer: those with urgent needs and those who obtain very little permission. For example, the “shanty towns” in Turkish cities, meaning “built overnight,” were shelters erected by migrants from rural areas on unowned land. By law or practice, if a family could quickly build a dwelling and occupy it before authorities noticed, the dwelling gained some degree of legal protection, forcing authorities to go through lengthy court processes to remove them. This tacit permission allowed hundreds of thousands of urban poor to build their own homes—something neither the market nor the state would do—and construct the outskirts of their cities. Similarly, Brazil’s favelas were also built by those excluded from official housing. These communities are constantly threatened with eviction or redevelopment, especially when land values rise. For example, ahead of the 2016 Olympics in Rio, many favelas in desirable locations were targeted for removal or “improvement,” which many local residents saw as a veiled attempt to displace them. At the same time, some favelas, such as Rocinha or Vidigal, have been subjected to internal gentrification as adventurous foreigners purchase property there for the scenery or culture, driving up prices—a complex situation that shows even informal neighborhoods are not immune to market pressures. Another form of bottom-up construction is the squatting of unused buildings—seen in cities from New York (where artists squatted abandoned buildings in the Lower East Side in the 1980s) to European cities with organized “squatters’ rights” movements. These actions demand space in the city for those who cannot afford market rents and often transform abandoned structures into vibrant community centers. A notable example is Metelkova in Ljubljana, Slovenia, a former military barracks that was occupied by artists and activists in the 1990s and transformed into an alternative cultural center. The very existence of Metelkova raises the issue of property ownership: while official institutions have left the space to decay, squatters have effectively taken possession of it through use and creativity. Over time, such squats can become legally recognized, as in community land trust projects or legalized squats in some European cities, confirming that those who care about and act on a space have a legitimate stake in it.

In summary, construction and displacement policies are swinging like a pendulum. On one side, wealthy contractors and newcomers are building shiny new urban futures, often at the expense of existing communities. On the other side, marginalized groups are building their own shelters and communities, often through necessity or protest, and often without official sanctions. The city is a patchwork of these efforts. Gentrification reverses previous disinvestment, but tends to push out people who have endured lean years. As an infographic on rising rents and displacement will show, as soon as the median income and property values in a neighborhood begin to rise (the “heat map” of property values turns from blue to red), the original low-income population begins to shrink — either they move to cheaper areas or, in the worst case, become homeless. Any “urban renewal” should ask the question: Renewal for whom? And any celebration of revitalization should be tempered by the voices of those who feel that revitalization is synonymous with eviction. Ultimately, who can build is often determined by who has the capital and permission—but who gets pushed out can be a political choice. Cities like Berlin have sought to break the link between neighborhood improvement and displacement by creating stronger tenant protections and social housing. In some places, community groups themselves are becoming developers through land trusts or cooperatives to ensure that local residents benefit from improvements. These struggles underscore that the right to remain in and shape one’s community is as much a part of “owning” a city as owning property.

Can Design Democratize Urban Space?

Amidst the power struggles over skyscrapers and neighborhoods, a promising question emerges: Can design itself help redistribute power and agency in the city? In other words, can architects and planners use their tools not only to serve the elite or reinforce the status quo, but to democratize urban space—to include marginalized voices in the design process and outcome and create more equitable environments? This theme explores participatory design models, examples of community-focused architecture, and the evolving role of architects as facilitators of democratic space creation.

One approach to democratizing design is participatory planning and co-creation. Traditional top-down planning has often led communities to feel disempowered (remember Jacobs’ criticism of “a few people deciding the future of the city behind closed doors”). In contrast, design methods such as charrettes bring residents, stakeholders, and designers together in collaborative workshops to shape plans from the very beginning. Community meetings, visioning exercises, and even interactive mapping can give local residents a direct say in what gets built—whether it’s a park redesign or a housing development project. In most cases, this leads to outcomes that are more aligned with local needs (because who knows a neighborhood better than the people who live there?). For example, tactical urbanism is a participatory approach in which citizens implement temporary street improvements (such as painting a crosswalk, creating a pop-up bike lane, or setting up a park) to demonstrate possibilities and build support for permanent changes. Many cities from New York to Bogota have adopted this approach, sometimes even institutionalizing it (New York’s DOT Plaza Program began with low-cost interventions and later evolved into beloved public squares). These practical tactics embody a democratic ethic: “Try it together and improve it.” Similarly, community land trusts (CLTs) and cooperative housing models place land ownership and design decisions in the hands of neighborhood residents and local nonprofit organizations rather than profit-driven developers. By removing land from speculative markets, CLTs ensure that improvements (such as new affordable homes or gardens) benefit the community and remain accessible in the long term. In cities like Boston (with the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative) and London (with CLTs emerging in some districts), residents literally drafted their own master plans and then took control of the land to implement them. This reverses the typical scenario—the community is the client and the designer, architects work for them, and the community owns the outcome, thereby avoiding displacement.

Most importantly, democratizing space also means prioritizing marginalized voices in design processes. A powerful example comes from Chile, where architect Alejandro Aravena and his firm Elemental developed “additive housing,” a participatory approach to social housing. Recognizing that budgets are too limited to provide every low-income family with a complete home, Elemental designed half-built houses: a sturdy two-story concrete frame with basic amenities, leaving empty spaces that families can fill in over time according to their needs and means. This approach (used in projects like Quinta Monroy and Villa Verde) treats residents not as passive recipients of a small home but as co-creators who will complete and customize their homes over time. The design process involved discussing priorities with families—do they prefer a good kitchen now or an extra bedroom?—and planning the “half-house” accordingly. By structuring the process through resident representation (they would either physically build the remainder or hire local contractors), Aravena saved costs while strengthening the community. In fact, architects focused on ensuring that the most challenging aspects of building a home for a low-income family—such as a sturdy structure, plumbing, and a weather-resistant roof—were properly constructed, leaving flexibility for the rest. This participatory philosophy earned Aravena the Pritzker Prize; as stated in Elemental’s handbook, they “believe in and value a participatory design approach” and see the architect’s role as utilizing the community’s “design power” in addition to their own expertise. The results were striking: years later, someone visiting these neighborhoods can see a rich variety of extensions—some families added bedrooms or workshops to empty spaces, painted walls in vibrant colors, and personalized their homes. The basic structural safety and dignity have been ensured, but the final form was not written by a distant architect, but collectively by the neighborhood residents. This model demonstrates that designing with people (especially those normally excluded due to poverty) rather than designing for (or against) them leads to more equitable and adaptable environments.

Participatory architecture in action: Chile’s “incremental housing” designed by Alejandro Aravena’s Elemental. Left, a basic half-house is being delivered—a sturdy frame containing a kitchen, bathroom, and a finished floor, but with empty space. On the right, homeowners gradually fill the empty spaces over time, adding walls, rooms, and personal touches. This democratized design allows low-income families to shape their own homes and communities rather than accepting a single standardized unit that fits everyone.

Another example of design empowering communities is the work of groups such as Raumlabor Berlin, an architecture collective known for its experimental urban interventions. Raumlabor typically enters neglected urban areas (vacant lots, abandoned buildings) and, more importantly, invites local residents to collaborate in building installations and opportunities. They define the city as a “space for action where new community ideas are built and tested” and claim that “this new approach has opened up urban and spatial production to a wider range of actors.” The architects act as facilitators and mediators in their projects: they organize participatory workshops, provide materials or scaffolding for community structures, and then step back to allow users to take ownership. For example, Raumlabor’s “Open House” project in Berlin took an abandoned house and, together with young people and artists from the neighborhood, transformed it into a shared space through DIY construction over the course of a summer. The process—people working together physically on their surroundings—is as important as the finished product and sows seeds of trust and skill within the community. As Raumlabor notes, “Participatory building leads to different and often surprising ideas… It helps identify issues that affect the environment… and lays the groundwork for a new culture of planning.” At their Osthang summer school and symposium in Darmstadt, Germany, they explored how involving citizens in temporary design/construction processes can make official planning more responsive and open. In these experiences, city residents were not merely consulted; they literally picked up hammers and paintbrushes to make concrete changes. The empowerment that comes from seeing one’s idea take physical form can spur further civic action (such as advocating at city hall or forming local associations to protect new spaces). At the same time, it redefines the architect’s role from that of a master builder to a collaborator or “mediator between various local interest groups.” This collaborative spirit (as mentioned earlier) is also seen in the “tactical urbanism” movement and in global projects such as Participatory Budgeting, where residents vote on small-scale urban improvements to be funded. For example, in Paris, citizens have proposed and selected hundreds of projects, many of which include design elements such as creating community gardens, building playgrounds, and painting murals.

Of course, democratizing design is not a panacea. It faces challenges: genuine community participation takes time; there are issues of representation (do the voices heard truly represent the entire community, or just the loudest ones?); and sometimes participatory processes can be collaborative or tokenistic (the dreaded “rubber-stamp” consultation where officials pat people on the back but ignore their input). Nevertheless, when implemented seriously, this approach can create more beloved and better-used spaces, because people see themselves in them. A noteworthy question has been raised: What role should architects play in the redistribution of agency? Increasingly, many architects (especially younger generations) see their role not as famous designers imposing their own vision, but as facilitators of social processes. This is consistent with theories of the “just city”—urban justice requires not only egalitarian outcomes but also inclusive processes (sometimes referred to as procedural justice). If a community that lacks adequate services participates in the design of a public space, it gains a sense of ownership that no top-down project could ever create. You can observe this in parks or playgrounds designed by the community: vandalism is generally lower and usage is higher because local residents feel that this is their own space. Even temporary interventions can shift power dynamics. The global rise of “Right to the City” ” (named after Henri Lefebvre’s concept that city dwellers have a right to shape urban space) includes everything from guerrilla crosswalk painters to federations of shantytown residents working with architects to plan better informal settlements. Each action challenges the notion that the city’s future is determined solely by officials or wealthy developers.

In summary, design can democratize urban space when it actively includes those who are typically excluded from the process. Whether through participatory planning sessions for a neighborhood plan, architects like Aravena who intentionally cede control to users in their housing projects, or nonprofit organizations that enable community-led development, the common thread is shifting authority to the people who inhabit the spaces. The best results seem to emerge when professionals and local communities respect each other’s technical and lived knowledge and create solutions together. Architecture, at its core, shapes how we live together; democratizing its creation helps ensure that the resulting spaces are inclusive, culturally rich, and responsive to human needs rather than profit or spectacle. As a community leader in a Rio slum neighborhood noted, the lack of maintenance and infrastructure in their neighborhoods stems from decisions being made “from the top down… we don’t participate… so we don’t get the results.” On the contrary, when they do participate, they achieve better results—the city becomes a little more their own.In summary, design can democratize urban space when it actively includes those who are typically excluded from the process. Whether through participatory planning sessions for a neighborhood plan, architects like Aravena who intentionally cede control to users in their housing projects, or nonprofit organizations that enable community-led development, the common thread is shifting authority to the people who inhabit the spaces. The best results seem to emerge when professionals and local communities respect each other’s technical and lived knowledge and create solutions together. Architecture, at its core, shapes how we live together; democratizing its creation helps ensure that the resulting spaces are inclusive, culturally rich, and responsive to human needs rather than profit or spectacle. As a community leader in a Rio slum neighborhood noted, the lack of maintenance and infrastructure in their neighborhoods stems from decisions being made “from the top down… we don’t participate… so we don’t get the results.” On the contrary, when they do participate, they achieve better results—the city becomes a little more their own.

Who Owns the Future of the City?

Urban planning is not just about today; it is a battle for the future. In the face of climate change, technological surveillance, and changing demographics, we must ask: Who owns the future of the city? This final question explores who will control the narrative and reality of cities in the coming decades. Will it be technology companies collecting urban data, governments strengthening cities against climate threats (and perhaps pricing out the vulnerable), or communities fighting for the rights of future generations? Urban planning policy now extends to data ownership, environmental justice, and long-term resilience—essentially, whose interests are being built in tomorrow’s city?

One of the most vibrant areas of this struggle is the emergence of the “smart city.” Around the world, municipalities are adopting sensors, cameras, and artificial intelligence systems to manage traffic, public services, and security. However, these technologies also bring with them a dimension of surveillance that raises questions about privacy and control. Who owns the data collected by tens of thousands of cameras and IoT devices in public spaces? If a city installs facial recognition cameras on every street corner, as some Chinese cities have done, does the future of that city belong to its citizens or to the state (or private technology vendors)? Google’s sister company’s proposed smart neighborhood project, Sidewalk Labs, has led to a cautionary tale in Toronto. The idea was to build a high-tech urban area filled with sensors that collect data on everything from trash cans to park benches in order to “optimize” city life. However, as people realized how much of their personal activities could be tracked and monetized, public backlash grew. Critics labeled it the “most advanced version of surveillance capitalism” and warned that tech giants “cannot be trusted to manage the data they collect about city residents securely.” In a letter written to the city by an investor, it is known that they stated, “No matter what Google offers, the value it will provide to Toronto cannot compare to the value your city is giving up… This is a dystopian vision that has no place in a democratic society.” The project was ultimately abandoned in 2020 amid these debates. This incident underscores that the ownership of the city of the future may depend on who controls its digital infrastructure and information flows. If left to large, profit-driven companies, there is a risk that urban areas will nudge people in ways they do not consent to or manipulate their behavior (imagine targeted advertising or algorithmic policing everywhere). It also raises an equity issue: will “smart” infrastructure primarily benefit wealthier areas (making them safer, more efficient) while neglecting poorer ones? Already, many applications labeled as “smart cities” (such as predictive policing algorithms) are accused of reinforcing biases—effectively excluding certain communities from benefits while intensifying surveillance over them. The struggle here is to insist that any technological future in cities remains accountable to the public. Some have proposed data trusts or commons to ensure that urban data is collectively owned rather than by a single firm. Others advocate for “privacy by design” by making anonymity the default setting in sensor networks. The key point: the intelligence of the city of the future must not become a new form of private property or authoritarian control that leaves citizens with no say. According to a Guardian report, even technology experts likened the Sidewalk plan to a “colonization experiment,” while a Canadian entrepreneur described it as the “calculated takeover” of urban data and governance by a private entity. Ensuring democratic ownership of the future means that smart city programs must be subject to careful public oversight and aligned with citizens’ rights.One of the most vibrant areas of this struggle is the emergence of the “smart city.” Around the world, municipalities are adopting sensors, cameras, and artificial intelligence systems to manage traffic, public services, and security. However, these technologies also bring with them a dimension of surveillance that raises questions about privacy and control. Who owns the data collected by tens of thousands of cameras and IoT devices in public spaces? If a city installs facial recognition cameras on every street corner, as some Chinese cities have done, does the future of that city belong to its citizens or to the state (or private technology vendors)? Google’s sister company’s proposed smart neighborhood project, Sidewalk Labs, has led to a cautionary tale in Toronto. The idea was to build a high-tech urban area filled with sensors that collect data on everything from trash cans to park benches in order to “optimize” city life. However, as people realized how much of their personal activities could be tracked and monetized, public backlash grew. Critics labeled it the “most advanced version of surveillance capitalism” and warned that tech giants “cannot be trusted to manage the data they collect about city residents securely.” In a letter written to the city by an investor, it is known that they stated, “No matter what Google offers, the value it will provide to Toronto cannot compare to the value your city is giving up… This is a dystopian vision that has no place in a democratic society.” The project was ultimately abandoned in 2020 amid these debates. This incident underscores that the ownership of the city of the future may depend on who controls its digital infrastructure and information flows. If left to large, profit-driven companies, there is a risk that urban areas will nudge people in ways they do not consent to or manipulate their behavior (imagine targeted advertising or algorithmic policing everywhere). It also raises an equity issue: will “smart” infrastructure primarily benefit wealthier areas (making them safer, more efficient) while neglecting poorer ones? Already, many applications labeled as “smart cities” (such as predictive policing algorithms) are accused of reinforcing biases—effectively excluding certain communities from benefits while intensifying surveillance over them. The struggle here is to insist that any technological future in cities remains accountable to the public. Some have proposed data trusts or commons to ensure that urban data is collectively owned rather than by a single firm. Others advocate for “privacy by design” by making anonymity the default setting in sensor networks. The key point: the intelligence of the city of the future must not become a new form of private property or authoritarian control that leaves citizens with no say. According to a Guardian report, even technology experts likened the Sidewalk plan to a “colonization experiment,” while a Canadian entrepreneur described it as the “calculated takeover” of urban data and governance by a private entity. Ensuring democratic ownership of the future means that smart city programs must be subject to careful public oversight and aligned with citizens’ rights.

Another aspect of the future is climate resilience – and here the term “ownership” takes on both a literal and figurative meaning. Climate change is redrawing maps: rising sea levels, heat waves, and extreme storms are forcing cities to invest in defenses and make difficult choices about which areas to protect. This situation could exacerbate inequality: wealthy areas may have sea walls and green parks to absorb floods, while poorer areas may be left exposed or designated as sacrifice zones. The concept of “green gentrification” has already been observed: urban greening projects (parks, greenways, waterfront revitalization) that improve environmental quality often inadvertently increase property demand, displacing residents who would benefit most from cool trees and clean air. For example, the creation of the highly successful public space known as the High Line park in New York City accelerated gentrification in West Chelsea, transforming a low-rent warehouse district into a luxury residential area in less than a decade. Similarly, studies in cities across the US and Europe show that, without measures such as affordable housing requirements, property values tend to rise around new parks or restored riverfronts. Therefore, who will enjoy the “green” city of the future is a contentious issue. If sustainability features (solar panels, rain gardens, energy-efficient buildings) are only built in luxury developments, the city of the future could be both greener and more exclusive—a kind of eco-apartheid where the wealthy live in fortified, comfortable climate havens while the poor are left in heat islands and floodplains. Already, in climate-sensitive regions like South Florida, we are seeing market signals dubbed “climate gentrification.” In Miami, high-elevation inner neighborhoods (historically home to working-class communities like Little Haiti) have seen real estate investors buying land in anticipation that coastal properties will lose value due to flooding. A Harvard study found that real estate prices in Miami’s higher elevations are rising faster than in flood-prone areas, suggesting that “wealthy buyers hoping to escape rising sea levels could displace long-time residents of high-end neighborhoods.” In other words, the future ownership of urban high ground—literally the safest land—is changing. Even the Miami government has acknowledged this trend and allocated funds to study and mitigate what it calls “climate gentrification.” Who will own the city of the future, in a climate sense? Probably those who can afford to protect their property or move to safer areas—if cities don’t proactively plan to protect vulnerable communities and include them in adaptation planning. This could mean building affordable, resilient housing, not just fancy sea-wall-protected apartment buildings; or ensuring that low-income residents are not simply pushed out, but compensated and relocated to better conditions, for example by involving them in decisions about planned withdrawals from certain areas.

A rendering of the proposed Magic City Innovation District in Miami’s Little Haiti—a large-scale “city of the future” development featuring sleek high-rises, tech offices, and green public spaces. Critics argue that such projects risk displacing local communities (in this case, a historically Haitian-American neighborhood) under the guise of innovation. Who benefits from such futuristic visions? The challenge here is to ensure that the city of the future is not solely for wealthy investors and newcomers, but that existing residents are also included in the planning and share in the benefits.

Finally, consider the idea of intergenerational ownership of the city. True sustainability means designing cities that serve not only current residents but also future generations—children who are not yet old enough to vote or consume, or who have not yet been born. Do we “own” the city only for the duration of our own lifetimes, or are we stewards passing it on? If a city is designed to outlive us, this implies choices such as conserving natural resources, building resilient infrastructure, and preserving affordable housing so that our children and their children can thrive here. Yet much of today’s urban development is temporary or short-sighted, driven by the pursuit of immediate profit. Luxury apartment towers often have a lifespan of only a few decades before requiring major renovation—will they become dilapidated shells that future taxpayers will have to deal with? Technology-driven solutions may become obsolete long before 2100 or require expensive upgrades. Meanwhile, slow-developing crises such as housing shortages and social segregation, if left unaddressed, could threaten the social fabric that future cities will need. Some urban thinkers are concerned about a “surveillance-driven, exclusionary city”—for example, if facial recognition systems are used to bar certain people from certain areas (a tool that could be considered for private retail centers and even some policing strategies), we could envision a future where large parts of the city are off-limits to people deemed undesirable by an algorithm. This dystopia would clearly not be a city for everyone—a kind of customized, segregated urban archipelago. From an environmental perspective, if climate adaptation focuses on building refuges for the elite (there is talk of billionaire bunkers and floating private cities), then a wider population could literally be left out in the cold when disaster strikes. The term “climate apartheid” has been used by the UN to describe a scenario in which the wealthy escape the worst effects of climate change while the poor are left to suffer—in urban terms, imagine high-ground settlements with private generators and sea walls, and low-lying informal settlements that are flooded. Clearly, this is a future that must be avoided at all costs.

The future ownership of cities, technology governance, climate adaptation, and inclusive planning therefore depend on the decisions taken now. There are encouraging signs: movements for “data sovereignty” in cities, pressure for open-source smart city platforms, and privacy laws could help keep Big Tech in check. Similarly, the rise of Youth Climate Strikes and youth councils’ participation in city planning are injecting long-term thinking and representation of future generations into today’s decisions. Some cities are exploring legal mechanisms to embed future interests—for example, Wellington (New Zealand) has created a Chief Resilience Officer position, in part to ensure that the city’s plans consider their impacts 50+ years into the future. In terms of climate justice, communities most at risk (often low-income) are organizing to demand equitable resilience measures—not just “green” infrastructure that inadvertently paves the way for gentrification, but also protections and improvements that allow them to stay and improve their quality of life. An intriguing concept is “dignified climate withdrawal”; that is, if some areas are truly unsalvageable, residents should lead relocation planning and be prioritized for new housing elsewhere rather than being left to disperse without support.

Ultimately, who owns the city’s future? If democratic governance, social justice, and foresight guide urban planning, it can belong to all of us. Or it could fall into the hands of a few—technology companies that own our data, the wealthy who own secure neighborhoods, and the powerful who make decisions that benefit only the present or the privileged. Urban planning policy is a tool we can use to influence this trajectory. By embedding values such as equality, privacy, and sustainability into today’s plans, we collectively take ownership of the city’s future. The city’s future should not be a dystopian shopping mall or a walled garden for the lucky few; it should be a resilient shared space. Achieving this means expanding public participation (bringing all previous sections—horizon line, mobility, development, design—into a future-oriented framework), protecting against new forms of exclusion, and above all, remembering that the city is a human project over time. As Lefebvre envisioned, the right to the city includes the right to shape the city’s future. Who owns this future? Ideally, those with the most at stake—that is, the general public and future generations, rather than any temporary coalition of capital and political power. The work of planners and architects in the coming decades will largely determine whether cities will remain , inclusive, democratic spaces or increasingly commodified and gated. The answer will emerge in smart city charters, climate action plans, housing policies, and daily civic participation—essentially, in our commitment to make the city of the future belong to everyone.

Conclusion

When we asked, “Who really owns the city?”, we embarked on a journey from the skyline to the streets, from the past to the future. The answers are multifaceted: developers and capital shape much of the skyline, but communities like Jane Jacobs’ can come together to defend a vision of livable streets. Mobility and access are unequally distributed—highways and gated communities have fragmented urban commons, but transit equity and spatial justice movements are working to reconnect them. Gentrification shows how easily those with resources can displace those without and rebuild in their place—a cycle rooted in historical injustices like redlining and now challenged by grassroots organizing and claims to the right to stay by the same communities. We have seen that design can be a democratizing force: from participatory parks to half-houses for the poor, when architects create alongside residents, the resulting spaces better reflect collective needs and empower underserved communities. Looking ahead, the battle over the future city—shaped by ubiquitous technology and looming climate impacts—will determine whether our cities remain inclusive living spaces or become fragmented, privately controlled zones.

A common theme runs throughout these narratives: the power of inclusivity against forces of exclusion. In moral and social terms, the true “ownership” of the city belongs not to any one group, but to the many people who live in it, use it, and give it life. Public space, affordable housing, accessible transportation, and participatory planning—these are the mechanisms through which the city is collectively owned and shared. Conversely, when architecture becomes merely an asset class for investors, infrastructure serves only those with cars or means, development displaces rather than uplifts, and the benefits of a sustainable future accrue solely to the elite, the city’s “owners” become a narrow clique and the social contract erodes. Reclaiming ownership in the broadest sense means insisting on the “right to the city” for all urban residents: the right to shape the horizon, move freely, stay in one’s home, participate in design, and have a say in the city’s destiny.

Urban planning policy is the negotiation of these rights. It is a struggle between private interests and the public good, between exclusionary and inclusive visions. The cases and theories we discuss show that, despite their significant influence, money and power do not have the final say—public activism, enlightened policy, and innovative design can steer urban development toward equality. Every zoning meeting, every social design workshop, every climate resilience task force is an arena where the question “Who owns the city?” is answered in real time. The most equitable answer is: “All of us, together.” Achieving this means democratizing the processes and benefits of city building. The horizon can reflect collective pride instead of private profit; streets can welcome every pedestrian, rider, and wheelchair user; development can mean revitalization without displacement; design can give voice to the voiceless; and the city of the future can be one where technology and nature serve everyone, not just a few. Such a city—collectively owned, managed for the future—is the true promise of urban life. Reaching this point will require careful and creative thinking, but as long as people continue to ask these difficult questions and fight for an inclusive vision of the city, there is hope that urban spaces can truly belong to everyone who calls them home.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.