For centuries, hallways have quietly held our homes together. These narrow passages were not just wasted space; they were the unifying elements of home life. Hallways blocked noise between noisy living areas and quiet bedrooms, filtered bright light and drafts between outside and inside, provided a stage for coming and going rituals, stored coats and secrets, and provided a soft transition from public to private space. However, in recent years, we have largely eliminated hallways. The rise of open-plan living, builders’ obsession with net-gross efficiency, and a modern design culture fixated on “flow” made hallways redundant—they were seen as empty space that could be incorporated into larger rooms. But this loss is tangible: more echo and noise, less privacy, chaotic entry rituals, and fewer thresholds where everyday communities can form.

This feature reevaluates the modest corridor not merely as a circulation space, but as a compact climate control device, a social concentrator, and a cultural scenario of daily life. We structure the discussion around five main questions, ranging from historical lessons spanning from Europe, Japan, and Latin America to contemporary design checklists. Each section, drawing on architectural examples and research, argues that (intelligently) bringing back corridors can improve privacy, acoustic comfort, climate resilience, and social cohesion in our homes.

Beyond Circulation: The Forgotten Functions of Corridors

What were corridors traditionally used for, and what have we replaced them with? In older homes, corridors weren’t just simple paths from point A to point B. They served as a buffer between public and private rooms, managing the “level of privacy” within the home. Separating entrances and living areas from bedrooms with an intermediate space, the hallway divided different living areas from each other. This not only reduced noise transmission but also provided an entrance choreography. One could pause in the entrance hall or living room before entering or leaving the house to remove shoes, greet guests, or compose oneself. Essentially, the corridor was a small spatial machine that balanced sound, temperature, and social roles.

Different cultures have developed their own versions of this threshold space. In Japan, the engawa became a typical example of a corridor used as a threshold. The engawa is a border area surrounding the edges of traditional houses, located between the inner rooms and the garden, resembling a veranda. Far from being a “dead space,” this area served many purposes: a place to sit and chat, a buffer against the climate and weather, a transition zone for removing shoes or observing the outside. Engawa allowed the building to remain open to breezes and views without causing the interior to get wet or overheat in rain or sun. In other words, it functioned as a passive climate regulator and the social boundary of the house. Similarly, the Japanese tōri-niwa – literally a dirt-floored corridor extending from front to back in classical townhouses – served as an “inner street” passing through the house. In Kyoto’s deep machiya row houses, a central earthen passageway connected the street entrance to the rear courtyard or garden. This tōri-niwa was typically open to the sky with a small light well or high roof, providing natural lighting and ventilation along the spine of the building. It separated the shop or reception area at the front from the kitchen further back (often called a hashiri-niwa) and even served a fire-preventative function. In short, it was a multifunctional corridor that ventilated, illuminated, and organized the house’s functions – essentially a narrow street running through the house.

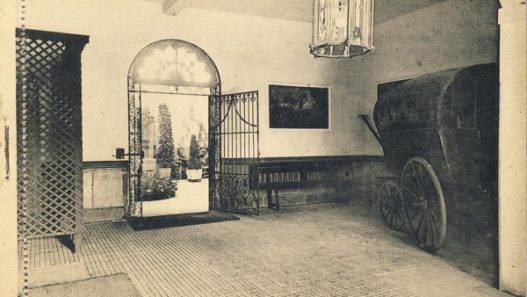

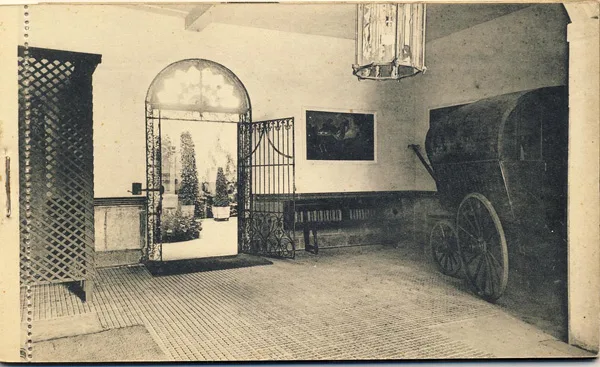

A similar model was also seen in Spain and Latin America. The zaguán, found in traditional colonial houses, is a deep, often grand corridor connecting the street door to the inner courtyard (patio). More than just a passageway, the zaguán was usually wide enough to accommodate carriages or horses, had thick walls, and featured a door opening onto the street. It blocked dust and heat from the street before one entered the family’s private courtyard. In places like New Mexico or southern Spain, this shaded passageway cooled the air entering the house and filtered those who could enter.

It served as a mechanical hinge between public and private spaces: work or guest rooms facing the street opened onto the zaguán, while more intimate family rooms were located further inside, around the courtyard. Variations on this theme can be seen throughout Latin America. For example, the casa chorizo in Buenos Aires (so called because of its long, connected layout) used a pasillo, a side corridor about 1.2 meters wide that ran from the sidewalk to the back of a narrow lot. This pasillo functioned as a small internal street providing access to a series of rooms or apartments arranged along a shared courtyard. Each dwelling was like a slice of the corridor, and large families or tenants could live in different units. The pasillo socially connected residents (they would encounter each other in this shared passage) and served practical purposes such as access and ventilation. These local solutions demonstrate that what we perceive as merely circulation can actually be at the heart of a home’s environmental and social performance.

In Europe too, corridors, entrance halls, and foyers once served an important threshold function. Think of classic terraced houses or railway apartments—a small entrance hall or foyer prevented cold drafts from entering the living room directly and provided a moment of pause between the city and the home. In apartment buildings without elevators, shared corridors and stairwells were places where neighbors greeted each other. All these examples emphasize that in recent years, we have not only opened up our floor plans, but also eliminated these small yet powerful mechanisms that provided acoustic separation, regulated temperature, and structured the rituals of daily life.

So, what did we replace them with? In many of today’s homes, especially in narrow city centers, the “open plan” living space has taken on the role of the corridor. Designers can maximize the feeling of openness by placing all rooms around a combined living/kitchen/dining area, rather than separating the living room and bedroom with corridors and doors. Coming home usually means entering directly into the living room or kitchen. By combining functions into a single continuous space, we gain a sense of spaciousness at the expense of clear boundaries. The result can be a kind of spatial chaos: the front door may open directly onto the television area; kitchen sounds and smells may spread uninterrupted into sleeping areas; there may be no quiet entrance hall to soften the transition from the busy outside world to the home’s private areas. In short, an efficiency-focused plan provides more usable square footage on paper, but potentially compromises on quality of use. While we may have gained a few square feet by eliminating hallways, sound, light, and social functions now collide in a single, formless “open” space.

(Featured image ideas for this section: An engawa overlooking the garden – title “The threshold as climate and social tool”; a diagram of a Kyoto machiya with a tōri-niwa – “A street passing through the house for light and air”; a photo of a colonial zaguán opening onto a bright courtyard – “The hinge area opening from the street to the courtyard.”)

Economics and Rules: How Efficiency Corridors Were Eliminated?

What are the economic and legal regulations that eliminate corridors from our floor plans? In a word: the pursuit of efficiency – or at least a certain understanding of efficiency measured in square feet and dollars. Developers and builders often focus on the net-to-gross ratio. This ratio expresses the ratio of a building’s saleable or rentable (net) area to its total area (gross), including circulation and structure. A private corridor inside an apartment or house is not usually counted as “livable space.” From a purely financial perspective, this corridor square footage appears to be wasted, non-revenue-generating space. Therefore, when every square foot must “pay for itself,” corridors are the first areas to be cut during value engineering. Why build a separate passageway when you can use a combined living space as a circulation hub?

Regulatory frameworks have inadvertently reinforced this trend. For example, the National Domestic Space Standard (NDSS), which came into effect in the UK in 2015, sets minimum gross internal areas for new dwellings of various sizes, as well as specific minimum room sizes for bedrooms and storage areas. These standards ensure that new homes are not unbearably small, which is good, but they focus on areas such as bedrooms, living rooms, kitchens, etc., and do not require any space for corridors. There is no “minimum corridor area” in the NDSS; it is sufficient for a design that complies with the standards to meet the total GIA and for furniture to fit into the rooms. This means that a smart plan that integrates circulation into other rooms can comply with the letter of the standards and appear more efficient. Developers seeking to meet these area standards (and marketing points) often squeeze or eliminate corridors to maximize the perceived size of living areas and bedrooms. In practice, as long as each room is accessible in some way and daylight requirements are met, providing this access by passing through another room is entirely legal and often encouraged by space criteria. Regulations that prioritize quantity (area) over quality (spatial hierarchy and separation) inadvertently encourage plans with very little or no transition space.

However, there are certain code requirements that ensure corridors are usable when they exist. Specifically, accessibility standards require certain minimum widths and clearances when a corridor forms part of an accessible route. In most regions of Europe and the United Kingdom, an “accessible and adaptable” dwelling (usually defined as Category M4(2) in building regulations) must ensure that all corridors and passageways are at least 900 mm wide and unobstructed. This is to enable wheelchair users to move around and to future-proof homes for people with limited mobility. These rules mean that if you add a corridor, you cannot make it arbitrarily small – you must allocate approximately one meter of width, which some designers consider a luxury in a compact apartment. Paradoxically, while these standards improve the quality of corridors (when provided), the fact that this space is deducted from the strictly controlled floor area may cause developers to refrain from adding corridors. In private projects without social housing requirements, compliance with the M4(2) standard is generally not mandatory, but many jurisdictions encourage it or require that a certain percentage of units comply with this standard. When this standard is met, at least the remaining corridors have sufficient width for usability.

Another factor is the interpretation of natural light requirements. Building codes typically require habitable rooms to have windows that let in daylight. If there is no window in a small interior corridor, this area is not considered habitable. This is not a problem, but modern buyers generally dislike dark, windowless areas. Therefore, architects try to eliminate or minimize corridors that would remain dark in the middle of the plan, or they “borrow” light using glass panels. In some cases, corridors are not designed so that every corner of the space can receive some natural light and a view, which is also a selling point. (Later, we will discuss how new design standards such as EN 17037 encourage access to daylight and “outdoor views” even for secondary areas, and we will imply that if corridors are reopened for use, they must receive daylight or borrowed light to avoid becoming gloomy tunnels.)

Simply put, market logic and certain regulations view corridors as a kind of luxury or waste. If you can combine all doors into a single open space and still meet building regulations regarding light, ventilation, and exits, why would you “waste” 5 or 10 square meters on a corridor? This mindset has become even more prevalent in cities where every square meter is valuable. Policies rarely question whether removing thresholds negatively impacts acoustic comfort, social rituals, or energy performance – these effects are subtle and long-term, while the pressure to reduce costs and meet minimum space requirements is immediate. As a result, many new apartments and houses, especially in densely populated areas, essentially consist of one or two multipurpose areas that open directly onto bedrooms, or even studio layouts where the concept of a hallway is completely absent.

As previously mentioned, the National Defined Area Standard leaves internal circulation open. At the same time, London’s aggressive housing targets have led to the development of many micro-units where designers have saved on “unnecessary” space. However, some design guidelines have recently begun to challenge this situation. The London Housing Design Guide (and updates made via the Mayor’s Housing SPG and draft LPG) states that the quality of circulation space is important for residents’ experience. It warns against designs with long, narrow internal corridors and single-aspect, deep units. In fact, the latest guide notes that external circulation areas (open-air access galleries) may sometimes be preferable, as they at least provide daylight and a social dimension in place of narrow internal corridors. We will address this issue in more detail in the context of multi-unit developments, but it is noteworthy that developers should be reminded: “avoid long, narrow corridors… short, daylighted, ventilated corridors or well-designed access decks are far superior.”

The elimination of corridors in modern times stems from economic efficiency and the lack of open layouts that preserve these intermediate spaces. Corridors have fallen victim to efforts to maximize usable space and simplify construction. However, as we will see below, what we have sacrificed may be compromising user comfort in ways we are only now beginning to measure.

What We Would Lose Without Corridors: Noise, Climate, Community

If hallways have largely disappeared, why should we care? What advantages do these narrow spaces offer that open floor plans cannot? By eliminating buffer zones in our homes, we are losing a great deal in terms of acoustic, thermal, and social benefits.

Acoustic Losses: Noise is not just a minor annoyance; it is also a health issue. The World Health Organization has established a strong link between exposure to environmental noise and sleep disorders, cardiovascular problems, and reduced well-being. One of the most common complaints in homes is the transmission of sound between rooms—for example, the noise of dishes or the sound of the television reaching the bedrooms. The hallway acts as an acoustic buffer. It provides extra volume and separation that prevents sound from noisy areas (living room, kitchen) from being transmitted to quiet areas (bedrooms, study). Without a hallway, each door typically opens directly into the main space, creating multiple direct sound paths through a single shared air volume. Consider a typical modern studio or one-bedroom home where the bedroom door opens into the kitchen/living room – any conversation or household appliance noise is just a thin door away from the sleeping person’s ear. In contrast, in a traditional layout with hallways, there is at least one door and several meters of air space to buffer sound. This difference can literally be the difference between a good night’s sleep and waking up to the hum of the refrigerator or a roommate’s late-night snacking. As cities become noisier and households become multi-generational or work-from-home focused, this acoustic distinction becomes increasingly important. Without hallways, people often have to resort to using earplugs, white noise machines, or endure chronic noise stress.

The need for acoustic insulation in apartments arises both internally (within the apartment) and externally (from neighbors and common areas). When an apartment opens directly onto an elevator or staircase, the first area—usually the living room—absorbs all the noise coming from the hallway or elevator lobby. Anyone who has lived in an apartment where the sofa is right next to the entrance door knows the sudden jolt when neighbors chat outside or the elevator ding is heard. A small entryway or foyer can absorb this sound, but in open-plan designs, this precaution is often not taken. Moreover, modern building codes address noise between apartments with insulation requirements, but we rely on regulation for noise control within the apartment. A good practice is to place “quiet areas on top of quiet areas,” meaning in multi-story buildings, placing bedrooms on top of other bedrooms rather than on top of someone else’s living room, and avoiding placing plumbing or elevators next to bedrooms. Hallways can act as a natural buffer zone for noise: in many older concrete block buildings, hallways were placed between apartments or between living and bedroom areas to isolate noise. Some contemporary design guidelines (e.g., London’s housing design guidelines) explicitly encourage interior layouts that minimize noise transmission and note that placing noisy rooms back-to-back and using transition areas to separate them increases comfort. Essentially, a corridor is the simplest tool for achieving acoustic zoning within a home.

Heat and Climate Losses: Hallways can also be thought of as heat buffers. Especially in climates with very hot summers or very cold winters, these intermediate spaces help soften the transition. In cold climates, the entry hall or vestibule acts as an air lock—when you open the front door on a freezing day, the cold air stays in the vestibule instead of cooling the entire living room. This is precisely why most traditional European homes have a small vestibule or a second door. In warm climates, a shaded corridor can pre-cool incoming air or provide cross ventilation without direct sunlight. Japanese engawa and tōri-niwa are again instructive examples: the engawa, which wraps around the outside of the house, is usually cooler and airier; it is a place to catch air currents. The earthen-floored tōri-niwa of Kyoto homes helped regulate temperature by connecting front and rear openings—essentially creating a wind tunnel that could draw heat out in summer. It also separated the kitchen’s heat and smoke from the rest of the house. In today’s open-plan apartments without corridors, the problem of the kitchen overheating adjacent rooms while cooking is common. Conversely, when you want to limit heating/cooling to a single room (for example, only heating the bedroom at night), this is difficult because everything is within a single volume.

If corridors were lit by daylight (from a window at the end, a skylight, or another source of light), they could even serve as low-energy climate buffers – warming up slightly on sunny winter days and spreading this heat into the interior, or drawing warm air upward and outward through stack ventilation. Such “thermal corridors” were common in traditional architecture. For example, the zaguán in colonial houses was typically a thick, cool area that trapped dust and heat from the street, allowing less of it to enter the courtyard. In modern passive design, one can imagine a narrow sunroom or enclosed porch serving as a corridor that regulates fluctuations in the interior climate. However, our modern small homes without corridors lack this breathing space. Since each room’s door opens directly onto another climate-controlled area, temperature changes are less buffered. An open layout can make it difficult to zone heating and cooling—you have to heat the entire studio because you can’t separate the bedroom from the kitchen. This can negatively impact energy efficiency. Indeed, a compact apartment with a central hallway that you don’t actively heat or cool can act as insulation between the warm interior and the cold exterior, reducing overall energy consumption. These effects are nuanced, but as we face climate change and more extreme temperatures, having an extra buffer zone (even a small hallway) can help homes passively survive during heat waves or cold snaps.

Social and Ritual Losses: Not all effects are physical; some are cultural and psychological. Hallways and entryways support certain micro-rituals and social courtesies that are lost when we eliminate these spaces. Consider welcoming guests: In a home with a hallway, you invite someone inside and pause in the entryway or foyer while your guest removes their coat, perhaps exchanging pleasantries before proceeding to the living room. In a scenario without a hallway, the same action often places the newcomer directly in the middle of your kitchen or living room – “Come in… mind the couch… let me find a place for your coat.” The threshold moment becomes awkward or cramped. Similarly, saying goodbye at the door or coming home and finding a place to catch your breath and drop your bag are different experiences when there is a small entryway. The Japanese have encoded this ritual with the genkan (entry hall), even in the smallest apartments. This is a small area next to the door where shoes are removed and one formally enters the home. The genkan area is essentially a tiny corridor. Without this space, where would shoes, coats, and umbrellas go? In many open-plan apartments, these items end up scattered next to the door or in the corner of the living room, creating clutter and confusion between the “outside” and the “inside.” The elegant transition from public to private space that the hallway once provided is lost.

The disappearance of corridors in buildings (or at least their reduction to a minimum, shortening to unpleasant lengths) means the loss of daily social interaction between neighbors. A well-designed corridor can be a social catalyst—spontaneous encounters, quick greetings, a notice board, or a place where children can play under supervision. In modern high-rise buildings, elevators typically open into silence or into very short, hotel-like corridors serving several apartments. There is little opportunity for neighbors to meet spontaneously in a pleasant space. Older housing models did the opposite: they expanded corridors and used them like streets. A famous example is Park Hill in Sheffield, England. In 1961, architects Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith created 3-meter-wide access decks in this mid-rise housing complex—almost streets in the sky—for neighbors to use as shared front yards. These wide, open-air corridors (3 meters wide) mimicked the lively streets of old towns, allowing children to play, milk carts to pass, and residents to stop and chat. Indeed, Park Hill’s “street terraces” were praised for fostering a strong sense of community in the site’s early years. These terraces were not perfect, and subsequent maintenance issues negatively impacted the social environment, but the concept still holds validity: when corridors are wide, well-lit, and part of daily life, they cease to be dead space and become social space.

Even in a less radical way, a simple and pleasant corridor can revive the community spirit. Many of us can recall friendly chats with our neighbors at the mailbox or an open apartment door. If the only common area were an elevator leading to the lobby, such interactions might never have happened. Private elevators that open directly to luxury apartments are the most extreme example of this trend: they maximize privacy (and privilege) at the expense of neighborly relations. On a city-wide scale, it is possible to argue that this change has undermined social cohesion, or at least made buildings feel colder. In contrast, in old brownstone houses or buildings with staircases, sharing the landing or bumping into each other on the stairs creates a natural closeness over time.

In our designs where there are no corridors or only narrow, functional ones, we have eliminated these “in-between” moments that facilitate community life. One lesson learned from 20th-century housing experiences is that size and design matter, as seen in Scandinavian open-air galleries or the semi-enclosed “streets” in some Japanese apartment buildings. An interior corridor 1.2 meters wide serves a single purpose: walking. People do not linger here; the corridor is very narrow and usually windowless. However, a 3-meter-wide corridor that gets sunlight and perhaps has a view or plants becomes a place where you can sit and relax, where children can play at the edge, where a bench or bookshelf invites residents to use the space. The difference is huge. By making corridors partially very narrow and dark (easy to dismiss as worthless), we have lost something; if we had redesigned them a little more generously, they could have contributed to our quality of life.

Park Hill, 1961.

Regional Lessons: Walls of the World

Instead of reinventing corridors from scratch, we can learn from local architects who never forget the value of threshold areas. Europe, Japan, and Latin America offer examples of corridors that are worthy of their existence from an environmental and social perspective. How can these inspire modern design?

Japan – Engawa and Tōri-niwa: Japanese homes offer us a beautiful vocabulary related to thresholds. As previously described, engawa is a type of veranda or corridor surrounding rooms, usually with a wooden floor. In traditional houses, the engawa was clearly a multifunctional threshold: it was outside the paper shoji screens but inside the storm shutters, creating a semi-open room. Families would sit and chat on the engawa, children would play there, and the engawa visually and physically connected the house to the garden. Climatically, it provides shade in summer (protected by eaves), catches breezes, and even in winter, on clear days, it captures sunlight to slightly warm adjacent rooms. Importantly, it is continuous—you can walk around the house on the engawa—which introduces the idea of a circulation loop rather than a dead-end corridor. Contemporary architects in Japan have reinterpreted the engawa concept in narrow urban apartments, adding narrow sunbathing areas or enclosed balconies that function like mini engawa – space for plants, airing futons, or simply serving as a buffer zone between inside and outside. The message conveyed by the engawa is that even a narrow strip of space, just one meter wide, can significantly enhance a residence’s climate performance and social use. In modern terms, we can design a “climate corridor” along the facade of an apartment: imagine a corridor at the front of the apartment, separated by windows opening to the outside and sliding doors opening to rooms, allowing daylight to enter. This could be an internal veranda, a passageway that allows you to enjoy the view without leaving your apartment and allows air and light to reach deeper into the plan.

On the other hand, tōri-niwa provides insight into linear organization and flexibility. In the Kyoto machiya layout, tōri-niwa served not only as a circulation space but also as a work area (for example, artisans could perform dirty work on the earthen floor), a ventilation route, and a way to extend the small street frontage deeper into the lot. Modern row houses and even apartment layouts can mimic this by incorporating a multifunctional corridor, for example, from the entrance to a small rear light well. This space can also be used as a mudroom, laundry area, or a small work corner under a skylight, thus not going to waste. Japanese architects like the late Toshihiko Kimura experimented with “interstitial spaces” (essentially partially enclosed corridors or atrium-like areas) in residences to achieve engawa-like effects in dense apartment blocks. Japan’s local wisdom is clear: design your thresholds to serve multiple functions. Thresholds can simultaneously be an elegant social space (where you chat with neighbors or watch the rain in the garden), a buffer against hot/cold air, and a connection point that allows breezes to pass through.

Latin America – Zaguán and Pasillo: The Latin American approach, spanning from the colonial period to early 20th-century urban homes, offers another lesson: turn the corridor into the social backbone. The zaguán of colonial houses was often as important as the rooms themselves – with its large doors open, it was the public face of the house and regulated the passage from the street to the courtyard. In today’s terms, we could compare it to an apartment lobby extending into the building or a closed passageway that becomes an open-air sitting room. In places like Córdoba, Argentina, or Lima, Peru, many historic homes still feature these large zaguanes where visitors are welcomed and can wait in cool, shaded comfort before entering the private home. The pasillo seen in Argentina’s casas chorizo (and similar row houses in Latin America) is generally much narrower and more modest, but it provides a flexible, almost complex-like living arrangement. Thanks to the side corridor, multiple small dwellings can harmoniously share a single plot. Large families in Buenos Aires took advantage of this: the front section could be occupied by grandparents or the owner family, while the additional rooms down the pasillo could be occupied by adult children, cousins, or tenants. They all gathered in the central courtyard and passed each other in the pasillo, thus forming an established community while each unit remained independent within itself. This is very important today, as we grapple with multigenerational living and housing affordability. For example, a modern apartment building could reintroduce a semi-open pasillo connecting a series of compact studios with shared courtyard areas, thus reflecting ideas of communal living. Even within a single apartment, an extended corridor opening onto a small inner courtyard or terrace can evoke the zaguán-patio sequence, offering a small shared space within an apartment context.

A concrete example: Some architects in Latin America are revisiting the casa chorizo typology for renovation projects. Instead of closing off the pasillo, they are often highlighting it. An award-winning project in Buenos Aires transformed a historic casa chorizo into “La Casa Verde,” emphasizing the long corridor and the high doors of each room opening onto the courtyard, demonstrating how airy and adaptable this old circulation pattern could be when restored. Here, the pasillo was only 1.20 m wide (the old diez varas facade standard required this), but it doesn’t feel narrow because it is framed by doors and windows; it’s like a secret, light-filled path running through the house. We can learn that even a narrow corridor can be pleasant when it opens onto a courtyard or a view. The secret is that the corridor is not an empty, dark hall, but is integrated with the outside space.

Europe – Galleries and Monastery Courtyards: Europe has a complex history with corridors. On the one hand, older apartment buildings and row houses had separate living rooms, as mentioned earlier. On the other hand, mid-century modernism experimented with gallery-access blocks—essentially exterior corridors (balconies serving apartments)—and these experiments yielded mixed results. The bad reputation of some collective housing blocks gave the “corridor” a bad name (poorly lit, endless, prison-like galleries became a symbol of alienation). However, there are also positive lessons: In recent years, many European student housing projects and shared housing plans have revived the idea of a spacious, partially enclosed, and community-focused monastery or gallery. For example, in Denmark and Sweden, there are student dormitories with shared corridors on each floor that are 2 meters wide, even with windows overlooking courtyards, and along these corridors, there are benches or mini-kitchens, not just for passing through but to encourage more use. These can be called modern svalgångs (Swedish for open-access balconies) designed for social interaction. These designs acknowledge that when people live in small units, the corridor can become an extension of their living space if it is safe and inviting.

Park Hill’s legacy in Sheffield is also being reevaluated, as discussed. The site has been renovated to preserve its wide “sky streets,” and interestingly, new residents have begun using these streets in a manner somewhat similar to their original purpose. Outdoor furniture and plants have appeared on some terraces, and the community occasionally organizes events here. This demonstrates that even in a modern context, if you give people a semi-public space that is part of their daily route, they can use it in positive ways (as long as management allows). Another European example: London’s Barbican Estate is not entirely corridors—it is a mix of private corridors and public walkways—but it demonstrates vertical circulation layers. There are elevated walkways (raised pedestrian paths) connecting the buildings, which function like external corridors on a city scale, creating a unique community space for residents and the public. Again, the principle is this: if a corridor has sufficient width, daylight, points of interest, and a purpose beyond just an exit, it can be more than just a corridor.

A pattern emerges from all these local and historical examples. The best corridors are those that are multi-purpose and the right size. Corridors that are too narrow or too dark are truly wasted space. However, when made slightly wider, brighter, and more spacious, they become the backbone of social and environmental functionality. The engawa is a semi-open living room, the zaguán a reception hall and climate filter, and the gallery deck functions as the front porch of every home. The lesson for contemporary architects and planners is to stop viewing corridors as a cost center where circulation should be minimized and start seeing them as an opportunity to add value. In a small city apartment, it may not be possible to allocate much space to a corridor, but a cleverly used small area can be very useful (for example, a pocket 1.5 m wide at the entrance, where one person can sit or a coat rack can be placed, narrowing to a functional 0.9 m width). In larger projects, the solution could be to turn the hallway into a kind of open-air gallery that people can personalize (this also helps with cross-ventilation and daylight).

Design of the Return Corridor: Checklist

If we want to bring corridors back into residential design, how should we design them to add real value and avoid repeating past mistakes? This section provides a standard-compliant and practical checklist, serving as a kind of design guide for new corridors, addressing elements such as daylight, width, acoustics, climate, and community. Essentially, if architects and developers follow these principles, corridors will no longer be seen as wasteful but can be appreciated as “living spaces”.

1. Natural light first: Don’t let corridors turn into dark tunnels. Ensuring corridors have access to natural light is one of the top priorities. This may mean designing units so that one end of the corridor is aligned with a window or exterior door, or using glass panels, skylights, or light wells to bring in light from adjacent rooms or courtyards. The new European daylight standard EN 17037 even includes recommendations for “views to the outside,” acknowledging the psychological importance of visual connection to the outdoors. Although corridors are not primary living spaces, applying the spirit of this standard means providing all corridors with the opportunity to see the sky or a little sunlight throughout the day. For example, a small internal courtyard or a frosted window near the ceiling that receives light from a bathroom or bedroom window can significantly change the character of a corridor. Design guidelines also recommend that corridors in apartment buildings be naturally lit and ventilated whenever possible. The aim is to reduce the energy spent on lighting and make corridors more pleasant and less claustrophobic. Practically: aim for at least a minimum daylight factor or a few minutes of direct sunlight in the hallway area, and provide an outdoor view (even if only borrowed) so you can tell the time of day and weather conditions as you pass through the hallway. This prevents the hallway from feeling like a cave. People instinctively avoid long, dark passageways—they evoke danger or functional areas at the back of the house—whereas a corridor ending in sunlight or a plant encourages use. Therefore, when planning a layout, align the hallway with light. Perhaps it’s a glass panel at the front door and a skylight above the door in the living room directly opposite, so that daylight illuminates the hallway from end to end. Such small changes make a big difference.

2. Appropriate Width for Purpose: Meet the standards, then strategically exceed them. As stated, an accessible corridor should generally be at least 900 mm (approximately 3 feet) wide. This is a fundamental measure for functionality – it is sufficient for a wheelchair or two people to pass in a tight situation. However, a 900 mm wide corridor is not a suitable place to linger. The recommendation here is to selectively widen to create “pocket areas”. For example, by widening the corridor at specific points (such as the entrance area or in front of doors) to 1.5 or 2.0 meters, you can create a small bench, shelf, built-in cupboards, or a wider area where a person can pull over and chat. This does not mean that the entire hallway must be 2 meters wide (which could be very costly in terms of space), but occasional widening can transform a passageway into a small foyer or niche. In a family home, a small desk for homework or a gallery wall for family photos could be added in an extended area of the hallway. In an apartment building, the space next to the elevators could be widened to accommodate a seating corner or a notice board for community announcements instead of a narrow lobby. Many housing standards today call for wider common hallways: For example, the London Housing Design Guide specifies a minimum width of 1500 mm for common corridors in new buildings and even recommends increasing this to 1800 mm (approximately 6 feet) in high-density environments so that they can be used comfortably with baby strollers, wheelchairs, shopping bags, etc. The logic is simple: width = usability. When people don’t feel cramped, they can stop and chat, or children can sit down in the corridor to tie their shoes. A general rule is to increase the width by 30-50% at key points in the corridor (near entrances or where it intersects with other corridors), creating an architectural feature rather than a uniform tube. This also helps with furniture movement and accessibility without making the entire layout inefficient.

3. Acoustic Zoning: Use corridors to separate quiet and noisy areas. Plan the corridor to act as a buffer between private sleeping areas and shared living areas. Ideally, this means that bedrooms open onto the corridor rather than directly onto the living/dining room. This way, there are two doors between a sleeping person and someone watching TV or cooking. Also, group quiet rooms together along the hallway; for example, group all bedroom doors in one section of the hallway and add an extra door that can close off this wing (like a hotel suite). Meanwhile, the living room or kitchen can be at the end of the hallway, separated by this distance. This layout greatly reduces noise “bleed.” Many soundproofing design guides specifically encourage this type of layout (sometimes referred to as “stacking” rooms based on their functions). A design note in London recommends that when placing interior doors and arranging plans, care should be taken to ensure that the living rooms of one apartment are not right next to the bedrooms of another apartment – this indirectly encourages corridor-like separations. In detached houses, this is more about family harmony: a corridor allows one person to get up early and make coffee without immediately waking their spouse or child in the next room. Additionally, consider using the hallway for additional acoustic treatments: sound-absorbing wall coverings or curtains in the hallway can further reduce noise transmission. Think of old carpeted hallways – there was a reason beyond style for those carpets. You can achieve the same thing with modern acoustic panels or bookshelves that serve as sound absorbers in a wider hallway. By treating the hallway as an acoustic zone, you can create the feeling that you are entering a quieter part of the house when you step into the hallway from the bustling living room towards the bedrooms.

4. The Living Room as a Climate Control Tool: Consider the hallway as part of your passive heating strategy. Design-wise, this means using the hallway for ventilation, shading, and buffering. If possible, add shaded windows or ventilation openings to the hall. For example, a small openable window at the end of the internal corridor can allow hot air to escape (chimney effect) or cool night breezes to enter. If there is a high stairwell or atrium as part of the corridor, this is even better – it can act as a chimney to expel heat in summer. In humid and hot summer climates, such as Córdoba in Argentina or Osaka (Kansai) in Japan, these airy corridors (zaguán or engawa/tōri-niwa) were used in traditional designs to facilitate ventilation. We can replicate this with modern materials: for example, a section with shutters on a door that allows air to flow through the corridor. In colder climates (Berlin, Hokkaidō, etc.), use the corridor as a buffer in winter. A classic example is the German Windfang or entrance hall – a completely enclosed entrance hall that significantly reduces heat loss when the door is opened. In apartments, even an enclosed balcony or a shared internal corridor can act as a thermal barrier between the freezing cold and the heated apartment. Consider adding some thermal mass (exposed brick or concrete walls, tile floors) to the corridor, so it absorbs excess heat and releases it when the air cools, softening temperature fluctuations. In modern sustainable design, architects sometimes add “thermal labyrinths” or buffer zones; a well-designed hallway can be the poor man’s thermal labyrinth. No high tech is needed for this—think of it as part of your insulation and airflow plan. Paint sunny areas a light color to reflect more light. Add overhangs or awnings to corridor windows to prevent excessive heating in summer. Essentially, design the corridor not as an afterthought, but as a small room with a climate control function.

5. Social Aggregator, Not Anymore: Use circulation as a social space. Especially in multi-unit buildings, consider the corridor (or access routes) as an opportunity for neighbor interaction and social amenities. In some cases, this may mean opting for gallery access (open-air corridors running along the building’s exterior) instead of enclosed double corridors. A well-lit gallery, perhaps equipped with attractive railings and planters, can become a kind of linear porch for residents. As noted in the Greater London Authority’s housing guidance, enclosed external terraces can be healthier and more intimate than internal corridors, while also ensuring each dwelling has dual aspect for cross ventilation. If internal corridors are unavoidable, add features that encourage shared use: for example, a small seating area next to the elevator where someone can wait or two neighbors can chat. In some forward-thinking apartment designs, there are shared bookshelves or “gift shelves” where residents can leave books or items, turning corridors into mini-libraries. In communal housing projects, corridor windows facing the courtyard encourage residents to take breaks and perhaps engage in spontaneous conversations. The key is size + daylight = community: as mentioned, if you can make the hallway ~3 meters wide and filled with natural light, people will naturally start using it as an extension of their home. They can place a welcome mat or chair in front of their doors (as seen in some Scandinavian shared-gallery senior residences). Even on a smaller scale, a 1.5-meter-wide corridor could have a niche large enough for a chair or a planter. These human touches transform the corridor from a sterile buffer zone into a place with its own identity. Historical examples like monastery courtyards or medieval arched passageways remind us that circulation spaces were once the most valuable and preferred areas for contemplation—think of monks walking and meeting in the monastery garden. In modern apartments, we can create our own mini monastery courtyards.

Note: Security and privacy must be balanced with openness. Social corridors should not feel unsafe or overly public. Good lighting (no dark corners) and clear sightlines are important so that people can spend time there safely. Semi-public amenities (such as communal laundry rooms, mail areas, bulletin boards) should be located outside the corridors, in a way that enlivens the corridors but does not create obstacles or noise. The Park Hill terraces have been partially successful because they are spacious and their front doors open onto the terraces – this area can be naturally monitored and was embraced by the residents. Similar ideas can be used in a new design: for example, encouraging residents to use the area in front of their doors as a front porch according to pleasant rules (even providing special planters or seating areas as part of the building design). When people take ownership of this space, the corridor transforms into a small neighborhood. All of this makes high-density living more intimate and less anonymous.

The Corridor, As a Living Space, Not Just Empty Space

The disappearance of corridors in recent years may have been an overcorrection. Yes, endless dirty corridors are undesirable—windowless hotel corridors or narrow entrance halls where only shoes are stored are not missed by anyone. However, as we have seen before, the solution is not to eliminate corridors, but to redesign them. In Europe’s dense cities, Japan’s narrow urban plots, and Latin America’s courtyard houses, we see that previous generations found ingenious ways to use every space efficiently. Before air conditioning was invented, corridors ventilated homes; before soundproofing existed, they blocked noise; and before trendy terms like “semi-private space” emerged, they created a social transition area. By eliminating most of these small spaces, we didn’t just remove square footage from our floor plans; we also erased the ritual and resilience that those square feet provided.

Bringing back the hallway does not mean reverting to the labyrinthine layouts of the Victorian era or adding unnecessary space. It means designing smarter, more refined, more purposeful thresholds, ensuring they earn the space they occupy. Imagine apartments and houses where a narrow space running alongside and along one side of the entrance becomes the lungs (for daylight and air), the ears (for blocking noise), and the heart (for greetings and farewells) of the home. Such a corridor could be only one meter wide for most of its length, but if it is continuous and connected to the outside at certain points, it can make a small house much more spacious and livable.

At the community level, redesigning corridors can also help make our increasingly large and tall residential buildings more humane. Instead of isolating people in units separated by corridors or elevators designed for fire safety, we are creating a circulation design that encourages natural and unforced interaction between neighbors, such as bumping into someone at the mailboxes or saying hello to each other while watering your plants in the gallery. These are the threads that transform individual units into a community fabric. As we face challenges like urban loneliness, an aging population, and the need for more sustainable lifestyles, these “in-between” spaces become increasingly important. A building that facilitates a five-minute chat in the corridor could be one where people check on each other during a heatwave or share resources during quarantine.

Hallways are not dead spaces, they are living spaces. They are the transitional stage of daily life. By designing hallways intelligently—with natural light, acoustic insulation, climate control, and social corners—we can create quieter, cooler (or warmer), more intimate, and more harmonious homes. Hallways redesigned for the 21st century can make our increasingly smaller urban dwellings feel a little more human.