Walls do more than just hold up a roof; they mediate between inside and outside, absorb heat, buffer cold, and even shape cultural identity. As architects face climate change and energy constraints, the old choice between massive, thick walls and lightweight, thin ones is taking on new urgency. A heavy wall with thermal mass can store heat during the day and release it hours later, smoothing out day-night temperature fluctuations, while a lightly insulated wall responds quickly to temperature changes but relies on insulation to block heat flow. The right strategy depends on the climate: a strategy that works in a village in the Sahara may fail in a tropical city.

Thermal Mass as a Climate Moderator – How Do Heavy Walls Regulate Heat?

Thick, high-density adobe, stone, or concrete walls have long been used as passive climate moderators in arid and temperate regions. The secret lies in thermal inertia: When heat strikes a massive wall, it moves slowly inward and takes hours to reach the inner surface. This delay is called thermal lag. For example, a 50 cm adobe wall in a desert house can exhibit a delay of approximately 5-10 hours between the peak of the hot outdoor environment and the heat reaching the interior. When the stored heat finally spreads inward in the late evening, the outside air may have cooled down—meaning the wall can release its heat just as the night cools. Similarly, the wall absorbs heat from the interior at night and “releases” it the next day. The result is a mitigation of extremes: sudden increases during the day and drops at night are softened. Engineers measure this effect with a attenuation factor that can be as low as 0.05 for thick earth walls—meaning the inner surface only experiences 5% of the external temperature fluctuations. In high-mass buildings, the indoor climate remains significantly stable.

Daily temperature fluctuations for different wall constructions. A heavy earth wall (green line) dampens and delays the heat wave, keeping the indoor temperature almost constant, while a light wooden wall (orange line) closely follows the outdoor temperature fluctuations. (Data adapted from Australian climate design guidelines.)

In hot desert climates with intense solar radiation and large day-night temperature variations, this type of thermal inertia is a blessing. Traditional Middle Eastern and Mediterranean architecture has taken advantage of this: in places such as Egypt and Iran, thick mud or stone walls reduce daytime temperatures of 40°C to tolerable levels indoors, then release the heat during cool desert nights.

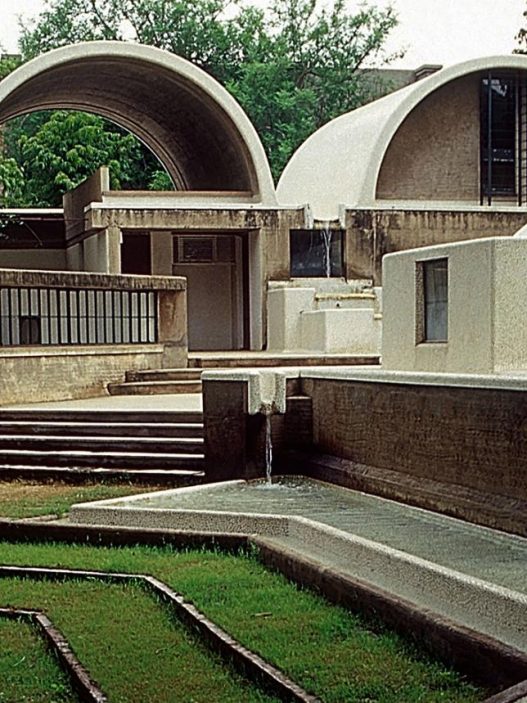

Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy revitalized mud brick construction in the mid-20th century, stating that modern concrete buildings “trapped and held heat unbearably, in contrast to traditional earthen interiors that remained cool during the day and released heat at night.” Mud-brick villages in Upper Egypt have demonstrated that walls 0.5 meters thick and domed roofs, with windows and courtyards carefully arranged for ventilation and shade, can keep interior summer temperatures approximately 10°C cooler than outside temperatures without air conditioning. In temperate climates, adobe walls and heavy floors can absorb excess heat, reducing the need for heating. In winter, a sun-facing stone wall acts as a heat battery; it absorbs solar energy during the day and gently warms the room after dark. Even on a smaller scale, a sun-exposed interior brick wall or concrete floor can reduce HVAC use by smoothing temperature fluctuations.

Thermal mass is largely dependent on climate, and there are times when heavy walls “bounce back.” In humid tropical regions or anywhere with a low daily temperature range, a thick wall will never have a chance to cool down. Consider a concrete or adobe structure in a humid coastal climate where daytime temperatures reach 30°C and nights remain at 27°C. The walls spend the entire day absorbing heat, but at night they find the air too warm to cool them down. By midnight, just as the occupants are trying to sleep, it radiates yesterday’s heat inward. Australia’s sustainability guide therefore states that “high-mass buildings are generally not recommended in hot and humid climates.” Lightweight wooden houses on stilts with ventilated walls have long been a local solution in tropical regions — they can heat up quickly in the sun, but they also cool down quickly at night, preventing the dreaded “oven effect” caused by heat escaping after dark. Research has confirmed that without adequate nighttime cooling, thermal mass can increase discomfort on hot nights. High-altitude and mountainous regions present a different challenge: thin air and cold temperatures can turn a large wall into a permanent heat sink. In a cold mountain climate with weak winter sun, an uninsulated stone or concrete wall will remain close to the cold outdoor temperature and draw heat from the interior unless you provide a constant energy supply. Therefore, in very cold regions, thermal mass is only helpful when combined with strong insulation and daytime heating (solar or furnace). A well-designed, high-mass home in a cold climate can maintain nighttime temperatures perfectly—but a poorly designed one will feel like a cold cave. General rule: thermal mass is most effective when daily temperature fluctuations are significant (~10°C or more) and is insufficient in consistently warm-humid or stagnant conditions.

In practice, architects must balance time delay and insulation for each context. The table below summarizes the basic performance measurements for heavy and light wall systems:

| Wall Type (Thickness) | U-Value (W/m²-K) – lower insulation is better | Time delay (hours) – heat delay | Reduction Factor – indoor emission reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rammed Earth (50 cm) | ~1.0 W/m²K (medium insulation) | 5-10 hour delay (heat flow in the late evening) | ~0.05 (95% attenuation in ambient temperature fluctuations) |

| Concrete (20 cm, uninsulated) | ~3.0 W/m²K (poor insulation) | ~6 hours (peaking in the afternoon indoors) | ~0.2 (some damping in oscillation) |

| Brick Cladding (brick + space + insulation) | ~0.5 W/m²K (good insulation) | ~2-3 hours (fast response) | ~0.3-0.5 (partial attenuation) |

| Wooden Frame + Fiberglass (15 cm) | ~0.3 W/m²K (high insulation) | ~1-2 hours (very fast response) | ~0.8 (minimum attenuation – traces visible in open air) |

Table 1: Typical thermal performance measurements for different wall constructions. High-mass walls significantly delay and reduce heat flow (low reduction factor), but steady-state U-values are high without additional insulation (indicating greater heat loss when the temperature is constant). Lightly insulated walls have low U-values (good insulation) but poor heat storage, so indoor temperatures fluctuate more closely with outdoor conditions. Sources: on-site measurements for adobe; building physics data for others.

The conclusion to be drawn here is that thermal mass is a double-edged sword: it can be your best ally for passive comfort or a hidden saboteur. With careful design—protecting a large wall from the summer sun, exposing it to the winter sun, and providing night ventilation—heavy walls can significantly increase comfort in the right climate. However, when used incorrectly in the wrong climate, you may find yourself fighting a tough battle against stored heat. Architects should evaluate climate data (especially daily temperature ranges and humidity) before deciding that “thicker is better.” In hot-humid regions, local wisdom often suggests the opposite: lighter is better—which brings us to our next topic.

Thin Walls in Extreme Climates – Lightness, Insulation, and Trade-offs

In climates where thermal mass performs poorly, builders have long favored thin, lightweight walls that emphasize insulation and ventilation. Two scenarios stand out: humid tropical regions where excessive heating and humidity are the main issues, and extreme cold regions where keeping heat inside (and condensation outside) is crucial. In both cases, wall assemblies tend to be thinner (in terms of material thickness) and lighter (using lower-density materials) and often incorporate air gaps or insulation layers to achieve their objectives. The trade-offs of these systems highlight the structural and environmental challenges of “thinning.”

Hot-Humid Tropical Regions: Traditional tropical architecture is a master class in lightweight, breathable envelopes. From the stilted bahay kubo of the Philippines to the open-air bale of West Africa, these dwellings use porous materials such as wood, bamboo, or reeds and typically have walls that are more curtains than solid barriers. The aim is to encourage maximum cross ventilation. Thin wooden slatted walls or woven bamboo panels allow air to flow freely.nın nüfuz etmesine izin vererek ısı ve nemi uzaklaştırır.

A lightweight wall also has low thermal capacity, meaning that when the evening breeze starts, the structure cools almost instantly – unlike a thick masonry building, which could still be radiating heat at midnight. As an engineer noted, in tropical nights, “light structures respond quickly to cooling breezes” and enhance sleep comfort. Culturally, this approach aligns with living in harmony with nature’s rhythm: walls can be opened, folded, and even removed (as in some Japanese summer pavilions) to transform indoor spaces into outdoor shelters. The obvious disadvantage of thin walls is their lack of thermal inertia—without shade, midday heat enters directly. Therefore, tropical designs combine lightweight walls with large roofs and deep eaves or verandas that prevent the sun from hitting the walls. Walls typically include operable ventilation openings or louvers (e.g., jalousie louvers) to expel hot air. Another consideration is durability: in hurricane-prone or termite-prone areas, fragile materials can be a liability. Historically, reeds and bamboo require frequent replacement, but modern versions use processed wood, fiber cement panels, or other lightweight yet more durable coverings. From an environmental perspective, these local tropical systems are excellent low-energy solutions—they essentially trade thermal control for airflow. Building occupants accept a closer connection with outdoor conditions (sometimes unfiltered sounds, odors, and even insects), but in exchange avoid the “thermal torture” of trapped heat.

Modern lightweight tropical walls are being developed to address some of these shortcomings. Architects are experimenting with double-walled facades for humid climates—an outer layer (such as perforated screens or greenery) to block the sun and prying eyes, and an inner layer of mesh or operable panels for security and rain protection. This creates a ventilated space that keeps solar heat from reaching the interior. Another innovation is the use of reflective or radiant barriers in thin roofs and walls to reflect infrared heat (common in contemporary tropical homes with metal roofs). The key criteria here are ventilation rate and solar reflection rather than time delay; success is measured by how cool the interior can remain with only natural airflow. This changes when users desire full climate control—for example, on a 35°C day with 90% humidity and no wind, even the best-ventilated house would be uncomfortable without mechanical cooling.

Lightweight structures do not buffer heat, so they are usually paired with air conditioning for the most intense conditions. This raises concerns about air conditioning dependency: a house made of thin steel and glass in Singapore or Miami could turn into a greenhouse when the power goes out. Architects must weigh this risk. A partial solution is to integrate heat insulation even in lightweight constructions (e.g., insulated wall panels or heat-reflective insulation under metal cladding). However, adding insulation to a tropical building can be a double-edged sword—too much insulation without proper ventilation can trap internal heat and moisture. Passive design experts recommend using low thermal mass plus selective insulation (especially on the roof) to allow buildings to cool down at night. Indeed, designs in places like Brisbane advocate for “highly ventilated lightweight structures and only modest mass insulation to avoid trapping heat.”

Cold climates: At the other end of the spectrum, thin wall systems are primarily emerging in cold regions through high insulation technologies and prefabrication. Historically, large walls (e.g., thick log cabins or stone walls) have typically been used to protect against winter in very cold climates—but these heavy walls have generally been supported by insulating materials (such as filling the gaps between logs with moss) or simply by their sheer thickness, which provides some insulation. In the 20th and 21st centuries, energy regulations sharply reduced wall U-values, making multi-layered lightweight walls dominant in cold regions. The best example of this is the Scandinavian or Canadian timber frame wall: a 2×6 (or deeper) wooden frame filled with fiberglass or mineral wool, clad on both sides, totaling perhaps 20-30 cm thick, but achieving U-values of 0.2-0.3 W/m²K (R-20 to R-30) U-values—significantly better insulation than a 50 cm-thick stone wall. These walls are “lightweight” in terms of thermal mass but highly effective at preventing heat loss. The benefits are immediately apparent: less heating fuel is required, and compliance with Passive House or similar standards is easier to achieve.

Structural exchange, on the other hand, is based on the thin, super-insulated walls being perfectly detailed: any gaps or “thermal bridges” (such as wooden or steel studs passing through the insulation) can create cold spots that invite condensation or mold. A heavy wall has greater tolerance to moisture (it can absorb and release some of it); a thin insulated wall with an improperly placed vapor barrier can trap moisture and deteriorate rapidly. For this reason, building science in cold climates places great emphasis on vapor barriers, airtight layers, and ventilation systems to keep thin walls dry. A well-constructed lightweight wall can perform admirably even in -30°C snowstorms, but a poorly constructed wall can leak air and form ice in the cavities.

Another challenge of walls in mildly cold climates is thermal sensitivity. These houses, which have low thermal mass, heat up and cool down quickly. This is a double-edged sword: on one hand, it’s convenient—you can quickly heat the house in the morning (unlike a stone cottage, which might take days to reach equilibrium). On the other hand, once the heating is turned off, the temperature drops rapidly. In the age of smart thermostats, quick response is often marketed as a feature (“heat only when needed!”), but flexibility suffers—a power outage on a winter night will be felt within hours. Some architects mitigate this by adding internal mass to specific areas, such as concrete floor slabs or a wall heater that stays warm (a stone stove). However, at its core, the thin-wall strategy for cold climates assumes continuous insulation and typically continuous heat input. Regulations like Passive House encourage adding more insulation rather than relying on mass: A Passive House in Sweden might have 40 cm of polystyrene in its walls, but minimal thermal mass inside. The result is an extremely stable indoor air temperature while the house is closed—the building effectively acts like a thermos bottle.

Here, compromise emerges in the experiences of building occupants: such houses may lack thermal inertia to buffer internal heat gains, meaning that on a sunny winter day, indoor temperatures may rise unless shading or ventilation intervenes (since the walls do not absorb excess heat). Some building occupants also report feeling “stuffy” due to the reliance of very lightweight, insulated homes on mechanical ventilation (an airtight, thin shell requires a source of fresh air). Acoustics is another consideration: while thick walls naturally block sound, thin walls require additional layers (plasterboard, insulation, flexible channels) to achieve equivalent sound insulation. Therefore, if lightweight constructions are not detailed for acoustics, privacy and tranquility may be compromised—consider how easily sound travels through a thin partition compared to a thick brick wall.

Structurally, thin wall systems typically rely on skeleton frames (wooden or steel studs) rather than the load-bearing mass of the wall itself to carry loads. This can be an advantage in seismic regions (lighter buildings have lower inertial forces) and offers flexibility in creating large spans or modular prefabricated panels. Many prefabricated housing concepts in Europe and North America utilize optimized thin walls: for example, a prefabricated panel may be only 20 cm thick, yet incorporate structured insulation, vapor control layers, and pre-installed services. Such panels can be shipped and assembled quickly, demonstrating the economic advantage of lightweight construction—material efficiency and speed. They also tend to use less raw material in terms of volume (especially if they have a wooden frame), which can mean lower embodied carbon if low-carbon insulation is used. However, if insulation or cladding materials are petroleum-based (foams, plastics) or contain a significant amount of steel, embodied carbon may increase. There is a stark contrast between a typical insulated stud wall (using fiberglass or wood fiber insulation) and an ICF (Insulated Concrete Form) wall: the former is made entirely of lightweight materials; the latter sandwiches a heavy concrete core between foam layers. ICFs offer excellent thermal performance and durability, but their cement content significantly increases embodied CO₂. We will revisit carbon impacts later—but it is important to note that “lightweight” walls are often compatible with the use of bio-based materials (wood, bamboo, straw), which can be far more environmentally friendly than cement and brick.

In summary, thin-walled systems are successful in both ends of the climate spectrum, but for different reasons. In hot-humid regions, they prevent overheating by shedding heat and embracing airflow, even at the expense of not storing coolness. In cold regions, they prioritize insulation to trap heat at the expense of not storing heat (thereby requiring constant input). Both face challenges—the former with overheating and noise, the latter with condensation and dependence on mechanical systems. Architects must use complementary strategies (such as shading and ventilation for tropical regions or airtightness and heat recovery ventilation for cold regions) to make lightweight systems successful. The next challenge is to find ways to combine the best of both worlds—heavy and light—leading to hybrid wall concepts.

Hybrid Wall Systems – Combining Mass and Lightness for Optimal Performance

If solid walls offer thermal stability and thin walls offer rapid insulation, why not combine them? This question has driven many contemporary innovations in wall design. Hybrid wall systems seek to capture “the best of both worlds” using a layered approach: typically, a high-performance insulation (to control heat flow) paired with and often completed by a lightweight protective cladding (to store and delay heat). In addition, advanced hybrids incorporate dynamic elements such as phase change materials (PCMs) or ventilated air cavities, effectively adjusting the wall’s behavior to the rhythms of the climate. The goal is a wall that can absorb heat when needed and release it when necessary, but without sacrificing energy efficiency. This is at the heart of passive solar design and many net-zero energy buildings today.

A classic example of a hybrid system is the Trombe wall, pioneered in the 1960s: it consists of a dark-painted heavy wall or concrete wall placed behind a glass layer with an air gap. Sunlight passes through the glass, heats the wall, and the heat is either transferred into the room through ventilation openings or transmitted after a time delay, while the glass and air cavity reduce direct heat loss to the outside. This is an early form of combining thermal mass (the wall) with insulation/delay (the air gap + glass acts as insulation). In modern versions, better glass (double or triple-pane) and sometimes a selective surface on the mass wall to retain heat are used. A properly designed Trombe wall in a sunny and cold climate can meet a significant portion of a home’s heating needs without using fuel. However, it can also lead to overheating in summer if not shaded—hence hybrids still require active control (shutters or ventilation openings).

In contemporary construction, the more common hybrid is simpler: thermal mass inside, insulation outside. For example, many high-performance homes have interior concrete or brick walls (or a concrete floor slab) inside the insulation envelope. The exterior walls can be thickly insulated wood or steel frames, but a feature brick wall, a water tank, or even just thick plaster within the conditioned space can add thermal mass. In this way, when the sun or internal gains (people, devices) heat the house, the internal mass absorbs excess heat, preventing sudden increases; at night, when the heaters are off, this mass gently redistributes the heat, preventing a sharp drop. Most importantly, the mass is inside the insulation, so it does not quickly release heat to the outside. This arrangement—“mass within insulation”—is recommended by energy experts because it maximizes the benefits of thermal mass. In contrast, the mass of an old, uninsulated stone building is exposed to the cold exterior and cannot retain heat effectively. By wrapping insulation around a heavy core (as in Insulated Concrete Form (ICF) walls or exterior-insulated wall construction), you create a wall that changes temperature very slowly inside. A study comparing ICF walls (internally and externally insulated concrete core) with traditional “tilt-up” concrete (mass on the outside, insulation on the inside) found that ICF keeps interior surfaces more stable and reduces peak heat flow, especially in climates with large temperature fluctuations. In a side-by-side EnergyPlus simulation, the ICF wall shifted the peak heat demand by 7 hours compared to a fully insulated wall, effectively flattening the load curve. These performance gains translate to lower HVAC usage and generally better comfort levels.

Another promising hybrid approach uses Phase Change Materials (PCMs) embedded in lightweight structures to mimic thermal mass. PCMs are substances that melt and freeze at room temperature, absorbing or releasing latent heat in the process (such as special waxes or salts). A thin layer of PCM can store as much heat as a thick concrete wall, yet it has a negligible weight. Researchers have integrated PCM panels or capsules into gypsum panels, ceiling tiles, or between stud cavities to act as an “invisible thermal mass.” For example, in a case study conducted in Iran, a BioPCM panel was added to the walls of a test house in a hot and dry climate, resulting in improved indoor temperature stability and reduced cooling requirements. The PCM layer increases the effective thermal inertia of the normally lightweight wall by absorbing heat during the day (thus preventing the room temperature from rising too quickly) and solidifying at night (releasing heat when temperatures drop). Experimental results have shown that cooling loads were reduced by 20-30% in some buildings enhanced with PCM. A report from Saudi Arabia noted a 20% reduction in cooling energy when PCM was used in walls compared to the same houses without PCM. This benefit is less pronounced in climates with a clear daily cycle (so that PCM can fully charge by cooling/melting) and where nighttime temperatures remain high (PCM never solidifies to release heat). The placement of PCM is also important: studies show that positioning the PCM layer toward the interior surface provides better comfort in warm climates (by absorbing indoor heat) and in cold climates, it can work better slightly inward from the interior to both capture indoor gains and store some of the sun’s heat from windows. PCM integration is still an emerging technology—cost and fire safety are considerations—but it is a compelling way to add thermal mass without adding bulk. Today, you can even purchase PCM-infused wall panels that look like standard drywall but can absorb several hundred kJ per square meter as they melt. When combined with standard insulation, this effectively transforms a thin insulated wall into a hybrid thermal battery.

Beyond PCMs, other hybrid strategies include green walls/facades and ventilated cavities for cooling. A vegetated green facade adds a shaded, evaporative cooling buffer in front of a wall—it is not a thermal mass on its own, but moderates how much heat reaches the wall, acting like a dynamic insulation that is more effective on hot days (when plants transpire) and thin enough not to impede cooling at night. In some buildings, active water-filled walls or capillary tube systems are used to remove heat by allowing a thin film of water to pass through the walls—essentially giving a lightweight wall the heat-absorbing capacity of water (which, incidentally, has a higher heat capacity per volume than concrete). These systems fall under the mechanical HVAC category, but they highlight a trend: combining passive and active elements to achieve the desired thermal performance. A research prototype combined a passive PCM wall panel with an active solar-powered water circulation system—water heated by solar energy during the day charged the PCM in the wall, and at night the PCM released heat into the interior, reducing heating energy by 44% in winter tests. Such complexity may not yet be common in residential design, but it demonstrates the potential of hybrid systems.

A simpler hybrid wall that is becoming increasingly common in sustainable architecture is the double stud or service core wall: a protective wall against external weather conditions (which may be prefabricated panels or cladding) and an internal structural/service wall with a space between them that is usually filled with insulation or even air. The inner layer can be heavy—such as cross-laminated timber (CLT) panels or concrete—providing strength and some mass, while the outer layer is a lightweight exterior cladding to protect against rain. The separation prevents thermal bridges and creates space for multiple layers of insulation. Many net-zero homes use this approach, essentially constructing a highly insulated shell with internal mass elements. For example, some designs feature a central concrete chimney or masonry stove (thermal mass) and super-insulated lightweight exterior walls—a hybrid at the building scale rather than the wall section scale.

The performance of hybrid walls is typically evaluated using dynamic modeling software such as EnergyPlus or WUFI, because steady-state R-values alone cannot capture time-delay benefits. These models generally show that adding internal mass reduces peak cooling loads and delays heating demand, which may allow for smaller mechanical systems or off-peak operation. In hot climates, hybrid walls help keep indoor temperature fluctuations within the comfort band for longer periods, extending the time before air conditioning is needed. In cold climates, they can maintain temperature for longer periods during a heating setback (useful for load shifting or if intermittent renewable energy is used for heating). However, a potential disadvantage is cost and complexity: a composite wall with multiple layers (structure, mass, insulation, cladding) may be thicker and more expensive to construct than a traditional single-wall system. Additionally, there are challenges related to moisture management—design must prevent condensation or allow it to dry without damaging the layers (especially if the mixture includes PCM or organic materials).

In summary, hybrid wall systems represent a design philosophy based on layering and integration. They acknowledge that a single material cannot meet all requirements (structure, insulation, thermal storage, moisture control, finish), so wall assembly becomes an orchestrated package. The potential benefits are significant: a well-designed hybrid wall can keep a building comfortable with minimal mechanical input, adapt to seasonal changes (some PCM walls can even be “tuned” to different phase change temperatures for summer and winter), and significantly reduce energy consumption. As we move toward net-zero and passive buildings, these composite solutions are becoming increasingly popular. Interestingly, the concept is not entirely new—it could be argued that the 19th-century brick cavity wall was an early hybrid (heavy interior wall + air cavity + exterior wall). What has changed are the materials (e.g., advanced insulators and PCMs) and the analytical tools we have to optimize them. In the next section, we will take a step back to see how culture and climate historically determined wall thickness and offer lessons that will resonate even as we innovate.

In the Context of Culture and Climate – How Did Tradition Shape Wall Thickness?

Long before the jargon of building science existed, people around the world developed wall systems that perfectly adapted to their surroundings, embedding cultural values into their walls in the process. The thickness (or thinness) of traditional walls was usually a direct response to climate, available materials, and the lifestyle of the inhabitants. In some cultures, walls have been monumental and permanent, while in others they have been temporary and flexible. By comparing these, we gain insight into the building philosophy in different contexts: permanence versus adaptability, insulation versus ventilation, fortress versus filter.

Consider the ancient Mediterranean and Middle East. Here, in regions such as the Middle Eastern deserts, North Africa, or the Mediterranean basin, massive rammed earth walls were the norm. Why? These regions were exposed to intense sunlight and heat during the day, cool temperatures at night, and often a scarcity of fuel or construction materials—but there was an abundance of soil, stone, and mud. The result: walls of earth and stone sometimes over a meter thick. For example, the walls of traditional mud-brick houses in the city of Yazd, Iran, are 40–100 cm thick (three mud-brick layers deep). In some Iranian deserts, walls up to 2 m thick have been used in fortress-like structures. These heavy walls served multiple purposes: structurally, they kept the buildings standing over time; thermally, their high mass moderated the harsh climate (as discussed earlier, delaying heat flow and softening daily fluctuations); and defensively, the thick walls provided protection against sandstorms and, in the history of frequently invaded cities, against attackers. The identity of a desert kasbah or medina house is tied to its heavy, closed walls, which offer cool shelter and privacy. “Thick walls with minimal openings” are defined as necessary for comfort and survival in Saharan architecture. These walls are usually made of local mud or stone and literally anchor the architecture to the ground. Culturally, they represent permanence and security. The house is a fortress against an inhospitable environment—a feeling captured in the Berber houses of the Atlas Mountains, where “thick mud walls help regulate indoor temperatures, keeping interiors cool in the scorching summers and warm in the cold winters.” At its core, for these cultures, wall weight equals comfort and security. The social life in such buildings often centers around inner courtyards or terraces—the heavy walls create an inward-looking sanctuary (such as a cool courtyard oasis) that reflects social values like privacy and family.

In contrast, look at Japan and other parts of East Asia (and many tropical societies). Traditional Japanese architecture is renowned for its lightness: paper-thin shōji screens, wooden frames, modular panels, and deliberately temporary materials. A Japanese house from the Edo period could be dismantled, its walls rebuilt seasonally (more open latticework in summer, more solid infill in winter), and, due to the wear and tear of the materials, it would typically be rebuilt every few decades. The Japanese approach prioritizes ventilation, flexibility, and connection to nature. As noted in a comparative analysis: “While space in Western architecture is enclosed by thick, heavy walls, in Japanese architecture, space is achieved using shōji, movable, thin and semi-transparent partitions.” In other words, walls in Japan were seen not as heavy dividers but as dynamic filters between the interior and exterior. The climate (most of Japan is humid subtropical) encouraged breathable designs. Thick walls could trap mold and heat in summer and pose a liability in earthquakes. Instead, lightweight wooden walls on a raised wooden frame allowed air to circulate beneath and within the house. They also responded to a cultural idea: Ma, the concept of space as something temporary and fluid. Paper walls allowed soft light and shadows to enter, making spaces feel more open and connected. They also facilitated an adaptable lifestyle—rooms could be reconfigured with sliding screens, something impossible with fixed thick walls. Of course, the downside was negligible thermal insulation. Historically, Japanese homes were cold in winter; residents adapted by heating themselves rather than the space (kotatsu tables, futons) and by embracing seasonal living (using verandas in breezy summers, closing them off with more mats in winter). The philosophy here is based on transience—buildings are not necessarily built to last for centuries (temples and castles aside), but rather to adapt to the seasons and be rebuilt when necessary. Ritual and tradition support this; for example, the Ise Grand Shrine is rebuilt every 20 years to reflect renewal. While extreme, this illustrates how a culture can prioritize renewability over longevity in materials.

There are many variations between these extremes. Europe offers an interesting middle ground: heavy stone or brick walls were common in temperate regions and the cold north (e.g., 60 cm thick solid brick walls in Victorian London houses or meters thick stone walls in a Swiss mountain house). These walls provided durability and some thermal mass, but Europeans also developed techniques such as cavity walls and insulation after fuel costs rose. The cultural aspect of Europe’s thick walls was often related to social status and protection—castle walls and villa walls were thick as symbols of power and to physically keep out enemies or noise. However, in residential architecture, the Industrial Revolution gradually introduced thinner, more standardized walls (such as stud partitions) that reflected a shift in priorities from sheer durability to cost and speed.

In the local architecture of Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia, thick earthen walls also had a spiritual/cultural dimension. For example, the thick walls and small windows in Middle Eastern houses are associated with the concepts of privacy and a cool, dim interior space as a sacred family area—the wall acts as a mediator of light and social interaction. Meanwhile, in many African and Pacific cultures where thick construction is not possible or necessary, we see walls as partitions rather than barriers. Some traditional homes in sub-Saharan Africa have no walls at all during certain seasons (open-sided structures with thatched roofs) – walls are an optional addition to block rain or cold winds. This reflects a worldview that seeks to be part of the environment rather than closed off from it.

It is also instructive to consider the availability of resources: cultures with easy access to stone or clay (such as the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and the Andes) tended to build massive walls. Cultures in dense forests (Southeast Asia, Pacific Islands) had access to wood and built lighter walls. In arid grasslands (some parts of Africa, Central Asia), neither wood nor large timber was available—lightweight tents (yurts, etc.) or, if possible, earth emerged. For example, the Mongol yurt is insulated with felt but fundamentally reflects a nomadic lifestyle with a lightweight, portable wall system. Compare this to a European medieval stone cottage fixed to a single location—it reflects the mobility or sedentary nature of an architectural society.

Philosophical Implications: The permanence of heavy walls is often associated with civilizations that value monumental architecture (the Romans, Persians, and Egyptians all built massive walls that are now in ruins) and the concept of heritage in buildings. A person living in a house with thick walls feels a sense of solidity and continuity. Many of these cultures have also developed rich decorations (stone carvings, thick mud niches, etc.) on these walls, expressing their identity through the building’s permanent structure. On the other hand, cultures with lighter construction traditions have often emphasized the quality of space over materials—for example, Japanese tea houses, where the subtle qualities of light passing through paper and the arrangement of spaces are more important than the material of the walls. Juhani Pallasmaa has written about how Japanese spaces “breathe” through light and shadow, while Western spaces enclose and frame. One is not necessarily better than the other—these are different emotional experiences. A Japanese house may feel liberating and in harmony with nature, but perhaps less private and sturdy; an Iranian courtyard house may feel protective and grounding, but perhaps more inward-looking and static.

Interestingly, with climate change and globalization, some of these historical solutions are being re-examined. Architects are asking the question: Can Berber mud walls or Roman thick walls teach us something about passive cooling that high-tech systems have forgotten? The answer is often yes. For example, architects inspired by Hassan Fathy have built new adobe homes in Sinai and New Mexico for modern living and found that 50 cm walls still work wonders (with a bit of moisture-proofing added). In contrast, the idea of flexible partitions and operable facades from Japanese tradition can be seen in today’s climate-responsive dynamic facades (even when made from modern materials). Thus, historical choices of thickness were not merely arbitrary—they were early solutions to local climate challenges and reflected how people wanted to live with or against nature.

To summarize this journey: Thick walls historically symbolized stability, coolness, and generally social conservatism—from Roman baths, where “thick concrete and brick walls insulated against the outside heat,” to Middle Eastern houses that provided citizens with a place to breathe, where life developed in the fixed comfort behind earthen walls. Thin walls, from Japan’s semi-transparent paper rooms that blend with gardens to the airy bamboo huts of tropical regions that tremble with every breeze, symbolized adaptability, openness, and transience. Each was a valid response to a specific climate-culture equation. Faced with a warming world, architects now confront the challenge of synthesizing these lessons—choosing thickness or thinness not out of habit, but through thoughtful analysis. In the final section, we explore how someone equipped with both modern data and ancient wisdom might make decisions about mass and light today.

Building for a Warming World – Choosing Between Mass and Light

As global temperatures rise and extreme weather conditions become more frequent, the risks associated with selecting the right wall system have never been higher. Architects must navigate a complex matrix of factors: local climate (both today and in 2050), building usage and occupancy patterns, energy sources (is power reliable? renewable?), and even the carbon footprint of materials. The question “mass or light?” becomes part of a broader design decision tree. The future points not to a single answer that fits everyone, but rather to climate-specific, hybridized choices guided by both quantitative analysis and qualitative assessments of comfort and culture. Here’s how architects can approach this dilemma:

1. Climate Analysis Comes First: The starting point is knowing your climate—not just the general category, but the nuances. This means looking at not just average temperatures, but daily temperature ranges, humidity levels, seasonal variations, and projected changes due to global warming. Tools such as climate zone maps (e.g., Köppen or local building zones) and psychrometric charts help identify dominant design concerns—for example, is the location cooling-dominant, heating-dominant, or mixed? A basic rule emerges from both local tradition and modern research: the greater the day-night temperature variation, the more thermal mass can help; the smaller or more humid the variation, the more ventilation and insulation are required. In many regions of the warming world, nights are getting warmer (nights warm up faster than days), which reduces the effectiveness of thermal mass because the cooling phase is shorter. For example, a city that once had an 15°C swing may only have an 8°C swing in 20 years due to higher nighttime temperatures—this shows that a design that favors heavy mass today may need to be rethought for the climate of the future. Architects are increasingly using future weather data to simulate building performance in 2030, 2050, etc., to ensure that a building optimized for today does not become uncomfortable tomorrow. Analysis may reveal, for example, that a city transitioning from a temperate climate to subtropical conditions will require more shading and lighter structures compared to the past. Conversely, areas experiencing more intense heatwaves but still cool nights may benefit from more thermal mass to buffer extreme conditions. Climate analysis also points to humidity issues: a warming world may become more humid in some regions, increasing condensation concerns on walls—suggesting that vapor-permeable, lighter assemblies may dry better than super-thick walls or that new ventilation strategies may be needed.

2. Comfort and Usage Patterns: Not all buildings are used 24/7. The choice between mass and lightness may depend on whether steady-state comfort or rapid adjustability is required. For example, an office building that is not used at night may be designed for a lightweight structure; you would not want a large structure that absorbs all the cooling from the air conditioning during the day but releases it hours later. A lightweight, well-insulated office can cool down quickly when the air conditioning is turned on each morning and does not waste energy heating/cooling the dead mass outside of working hours. On the other hand, a home or hospital used around the clock may benefit greatly from mass to maintain a constant temperature throughout the day. Additionally, user behavior is important: if building occupants prefer to keep natural ventilation (common in homes) closed at night in favor of a conditioned space, this will influence wall selection. Thermal mass is ideal for passive buildings (no HVAC) that maintain a natural temperature cycle; light weight is typically chosen for fully mechanically controlled buildings where HVAC does the heavy lifting and walls only need to be insulated. In a warming world with more frequent power outages and heat waves, designing for passive survivability is critical—basically, can the building maintain livable conditions for a period of time without electricity? Heavy mass can keep a building habitable for longer in both heat (by slowing temperature increases) and cold (by retaining heat), but only if the climate allows it to cool or recharge appropriately. This consideration can influence decisions for critical buildings such as emergency shelters or housing for vulnerable populations: for example, a well-insulated but lightweight high-rise apartment building could become too hot to inhabit during a heatwave with a few days of power outage (as tragically seen in recent events), whereas a heavy-mass building could remain cooler inside for longer and buy time for assistance. Such scenarios are increasingly becoming part of design criteria.

3. Carbon Footprint and Materials: Sustainability is not only about operational energy, but also about embodied energy/carbon. There is an important trade-off here: concrete and brick have a high carbon footprint (the cement industry alone accounts for ~8% of global CO₂ emissions), while wood or straw-based systems can be low- or even carbon-negative (by storing the carbon absorbed by plants). Therefore, choosing between a massive concrete wall and a lightweight wooden wall is also a choice between potentially pumping a ton of CO₂ into the atmosphere or storing it. For example, a simple comparison: a traditional foam-insulated and wood-framed 4×8 ft wall panel emits approximately 39 kg of CO₂ during production, while an equivalent straw bale panel can store ~78 kg of CO₂ (net negative emissions). This represents a significant difference of over 100 kg of carbon per panel. Therefore, from a climate change mitigation perspective, the use of dense concrete or fire brick is problematic unless mitigated through carbon capture or offsetting; the use of wood, straw, or earth materials is generally much less harmful. This means that architects need to carefully consider whether the benefits of thermal mass (which typically requires concrete/brick) can be achieved in a lower-carbon way. Options include stabilized earth with low embodied energy (adobe, compressed earth blocks) or newer low-carbon concretes and recycled masonry. On the other hand, if lightweight insulation is preferred, petroleum-based insulation such as XPS or spray foam should be avoided, as these contain high amounts of carbon and even potent greenhouse gases during production. Even if walls need to be slightly thicker to achieve the same R-value, more sustainable insulation materials (cellulose, mineral wool, hemp, straw) can be preferred. The thinnest walls (in terms of high R-value per cm) typically use high-performance insulation technology (such as vacuum-insulated panels or aerogels), so there is a balance between making walls super-thin and keeping embodied carbon low. Nevertheless, exciting developments are underway: aerogels and vacuum panels can achieve R-40 in just a few centimeters—great for retrofitting existing thin-walled buildings without adding volume. While costs and complexity are currently high, they could pave the way for ultra-insulated yet thin profiles in the future, potentially revolutionizing space-constrained urban renovations.

4. Regulatory Frameworks and Certifications: Passive House (Passivhaus), LEED, WELL programs and local energy codes will influence choices by setting performance targets. For example, Passive House does not mandate wall types, but its strict energy use limits effectively force designs toward heavy insulation and airtightness—resulting in many passive houses opting for thicker, highly insulated walls (typically 30–40 cm of insulation). However, Passive House also encourages the use of thermal mass for passive solar gain if climate-appropriate. LEED may reward the use of specific materials or strategies (recycled content, regional materials, etc.) that can support either approach depending on the context. For example, using local adobe can earn points for regional materials and passive design in LEED, while using certified wood framing can earn points for other categories. Some building codes in hurricane zones may mandate impact-resistant construction (e.g., using concrete/blocks instead of thin wood), while seismic codes in earthquake zones may prefer wood or steel (lighter materials) over heavy masonry. In a warming world, building codes themselves are evolving—in some regions, mandatory passive survival features or at least ensuring that buildings can withstand higher design temperatures are being discussed. This could mean requiring external shading or minimum thermal mass in certain climates to prevent unsafe overheating. Thermal comfort standards, such as ASHRAE’s adaptive comfort model, can also indirectly encourage designs that mitigate indoor fluctuations (mass helps with this). This is a dance between prescriptive rules and performance-based targets. Architects should use these frameworks as guidelines but still adapt them to the specifics of the project.

5. Future: Innovation and Synthesis: The ultimate choice between “mass and light” may soon become obsolete; instead, we will see new materials and methods that blur the line. Some interesting developments:

- 3D-printed walls use optimized geometry to provide both internal thermal mass and insulation. For example, some 3D-printed concrete or clay walls have solid parts (thermal mass) while creating hollow lattice structures that trap air (insulation). This can provide a structurally sound, climate-responsive, thick wall that is not solid material throughout—essentially a hybrid by design.

- Phase change gypsum board and insulating thermal paints are coming onto the market, which means that any wall (even a lightweight one) can gain some thermal storage by applying special coatings or finishes. Imagine a future renovation where, instead of adding a Trombe wall, you apply a “thermal paint” that increases the wall’s heat capacity. The first versions contain microencapsulated PCMs within the paint or plaster.

- Smart walls equipped with sensors and controls can actively manage heat flow—for example, ventilation openings in wall cavities that open at night to expel heat from the mass wall and then close during the day (thus effectively transforming a high-mass wall into a cool nighttime radiator). Dynamic insulation prototypes (where the insulation value changes according to conditions) are being researched. For example, a wall that is highly insulated (keeping heat out) in summer but less insulated (allowing solar heat to charge a thermal mass) in winter—perhaps using materials that change their conductivity or movable insulation panels.

- Nature-inspired solutions: Scientists are looking to termite mounds (essentially mud structures with intelligent ventilation) for clues. Additionally, incorporating living elements such as green walls that not only provide shade but also grow and change with the seasons, or algae-filled wall panels that produce shade and oxygen, can add a new dimension to wall design. These may not affect thickness but can add functional layers.

When making decisions today, architects should generally opt for a mixture: perhaps heavy floor coverings and interior partitions for mass, high-insulated lightweight exterior walls – or the exact opposite, depending on the climate. What matters is holistic integration: walls, roofs, windows, orientation, etc. are just part of the passive design toolkit. An old saying goes, “the best insulation is a well-designed building.” If a building can be oriented to minimize unwanted heat gain and maximize natural cooling, the mass vs. insulation debate becomes less critical—the building will perform well due to its overall design. However, with increasing climate extremes, it is wise to err on the side of caution: Design for the hottest expected conditions (heat dome events) while ensuring that thermal mass or super insulation (or both) can handle them, and design for flexibility (such as ensuring that a room in the building can passively remain cool as a refuge).

Decision Flow Chart (conceptual): Climate → Primary Challenge → Wall Strategy:

- Hot-dry desert → Large diurnal temperature variation → Insulated high thermal mass (thick adobe or concrete) to reduce heat flow at midday.

- Hot-humid tropics → Excessive heating and little cooling → Reflective insulation and shading with light, ventilated walls (wood/bamboo); use thermal mass only if actively cooled.

- Moderate/Mixed (Mediterranean, etc.) → Seasonal variation → Hybrid approach: mass for winter solar gain, insulation for summer; e.g., brick cladding or cavity walls.

- Cold (Continental/Polar) → Heat retention critical → Thick insulation (super-insulated wood/metal stud walls or structurally insulated panels); add internal mass if sunny or for off-peak storage, but focus on airtightness.

- High altitude/Alpine (sunny but cold) → Intense sun, cold air → Combination: walls (or floors) exposed to high solar mass plus insulation and glazing to store daytime sun, high insulation elsewhere.

- Urban Heat Island (Heating Cities) → Hot days and nights, limited daily relief → Active cooling or lighter structures with thermal mass, only nighttime cooling through cool breezes or mechanical pre-cooling is possible (perhaps using renewable energy during off-peak hours to cool the mass). Green facades and reflective surfaces to combat the heat island effect.

Finally, architects should keep in mind the perception and well-being of building occupants. Some people feel better in a solid, quiet enclosure; others prefer an airy, open environment. Thermal comfort is partly physiological and partly psychological. A large stone house naturally provides a sense of shelter (and actually usually superior acoustic comfort and low vibration), which can be calming. A light house may feel more connected to the outside visually and acoustically—which can be pleasant or disturbing depending on the context (the soft patter of rain on a thin roof can be soothing, but the howling of wind through the walls can be frightening). Biophilic design may favor more natural materials (wood, earth), which are typically compatible with heavy local (earth) or light local (wood) materials, depending on the region. When designing for a warming planet, we must aim not only for energy and temperature figures, but also for the well-being of the building’s occupants. Perhaps thick walls provide psychological comfort in chaotic times, or thin walls provide the connection to nature needed in an urban forest.

At the end of this section, the trade-off between mass and light is not a binary transition—it is a sliding scale with many combinations available. In a warming world, the best approach is often “mass where you need it, lightness where you can”: use enough thermal mass to buffer expected fluctuations and provide flexibility, and use highly insulated, lighter assemblies elsewhere to minimize energy loss/gain. Optimize orientation and shading so that whatever strategy you use, you play to its strengths (e.g., don’t let the sun hit light walls in summer, let it hit heavy walls in winter, etc.). And critically, consider carbon and life cycle—we want solutions that are not only climate-resilient but also climate-friendly. With thoughtful design, architects can create buildings that are cool in the heat, warm in the cold, energy-efficient, and respectful of their surroundings—whether it’s a 2-meter-thick compressed earth wall, a 10-inch SIP panel, or a creative sandwich made from materials that didn’t exist a decade ago.

Weight as Meaning – Rethinking Thickness in a Burning World

The debate over thermal mass in thin walls reveals something profound: the weight of a building—its physical heaviness or lightness—has meanings beyond engineering. It is an expression of how we relate to climate, time, and place. In ancient Jericho or Rome, thick walls meant survival and legacy (literally the concrete evidence of a civilization). In a Javanese or Japanese village, thin walls meant transience and harmony with the flow of nature. Today, as our planet warms and our technology advances, we have an unprecedented ability to choose our wall systems not just out of tradition or necessity, but with a clear intention.

The result is that neither heavy nor light is absolutely “better”—success lies in adaptation. A thick earthen wall that moderates a desert home is a brilliant move in context, but it would be a thermal disaster in a tropical swamp. A thinly insulated wall can keep a Passive House in Canada warm with minimal energy, but the same wall would turn a home in Niger into an oven without 24/7 air conditioning. Therefore, architects must become master climate interpreters who translate the conditions of a site into design decisions related to mass and insulation. This is not a new role—it extends to local builders who intuitively do the same thing—but it must now be carried out with the twin lenses of cutting-edge simulation and deep respect for low-carbon solutions.

More importantly, the wall thickness dilemma also serves as a proxy for balancing the past and the future. Thermal mass typically refers to traditional materials (stone, brick, earth) and time-tested passive strategies, while lightweight high-performance walls refer to modern materials (polymers, high-tech membranes) and industrialized methods. When rethinking thickness, we are actually synthesizing the wisdom of the past with innovation for the future. For example, by combining a centuries-old adobe technique with a thin aerogel insulation layer, we can create a wall that honors heritage while meeting tomorrow’s standards. Or we can use advanced engineered wood to create multi-layered panels that combine structural, insulation, and interior finish functions—a nod to old wooden walls but turbocharged with science. In a “burning” world (both literally, with forest fires, and figuratively, with climate change), our walls can be part of the solution: cooling us without wasting energy, protecting us without isolating us from the environment.

The poetry of walls should not be lost in this technical discussion. Walls create space—thick walls often create recesses, deep window sills, a sense of enclosure, and shadow, while thin walls create openness and a sense of proximity to the light and sounds outside. As Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa has noted, materials and shadows deeply influence our architectural experience. The weight of a wall can be felt by building occupants—stepping into a massive stone monastery versus a lightweight glass pavilion elicits entirely different emotional responses. As we strive for sustainability, we must also aim for architecture that nourishes the human spirit. In some cases, a heavier wall that provides a cool refuge and a sense of silence (and actually reduces stress during a heatwave) can be a boon for health, while in other cases, a light, daylight-filled environment enhances mood and connection to nature. Rethinking thickness means rethinking what we want the experience of living in that building to be.

From a planetary perspective, building lighter (using low-carbon, renewable materials) can significantly reduce emissions – but building smarter (being slightly heavier in the right places to reduce operational energy later) is also beneficial for the climate. The choice is a delicate life cycle balance: a concrete mass wall can save energy for 100 years but has a very high initial carbon cost; a straw bale wall is carbon negative but requires careful detailing to last 100 years. There is no such thing as a free lunch—but there are many nutritious options. Architects should utilize emerging tools such as energy models and life cycle assessment (LCA) calculators to find an optimum. Generally, hybrid solutions provide the best overall eco-balance (e.g., a mostly wooden structure with a few concrete elements for mass where truly needed, or the opposite using recycled concrete aggregate to reduce the footprint).

In climate-sensitive design, wall thickness is not merely a technical parameter—it is almost a philosophical stance on how a building relates to its environment and over time. As the climate crisis forces us to build differently, perhaps in some places thick, breathable walls – earthen structures, biomaterial composites – in other places, we will see a renaissance of incredibly thin, super-insulated cladding and composites that masterfully blend layers together. The “insulation versus thermal mass” dilemma will dissolve within a spectrum of sensitive designs. Old and new architects will continue to ask the fundamental question posed at the outset: How much and what kind of wall do we need between us and the climate? The answer will come from science, history, and creative experimentation.

Whether a wall is heavy or light, what matters is that the building as a whole remains comfortable, durable, and enriching for its inhabitants, while also having a light footprint on the earth. If we achieve this, whether it weighs tons of earth or consists of just a few panels of air and gel, then the wall has done its job. In a world that is literally heating up, rethinking our walls—the “skin” of our built environment—is a fundamental step toward a cooler and more sustainable future.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.