Across civilizations, large-scale buildings relied on durable materials and repetitive structural modules. For example, the ancient Egyptians built massive temples and pyramids of pillar and lintel construction using closely spaced stone columns and thick curved walls. As early as 2600 BC, Egyptian columns were carved to resemble bundled plants (papyrus, lotus, palm). Similarly, Greek architecture developed formal column styles (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian) that defined their own order. In later Roman times, the arch became dominant, complementing the classical orders. Other cultures made similar innovations: Mesopotamian builders constructed massive stepped ziggurats (terraced temple towers) as religious monuments, and Mayan civilizations built stone pyramids with wide terraces and broad staircases (e.g. El Castillo in Chichén Itzá).

- Egyptian columns During the Old Kingdom, architects such as Imhotep used stone columns in the form of bundled reeds (papyrus, lotus) with richly carved capitals. The Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak (New Kingdom) has 134 columns up to 24 m high, forming a “forest” of supports.

- Greek layouts: Classical Greek temples (e.g. the Parthenon) used modular Doric, Ionic or Corinthian columns in standardized proportions. These orders governed column height, fluting and entablature design. Later, the Romans adapted these orders, adding the round arch and vault and allowing much wider spans.

- Mesoamerican platforms: The Maya and other pre-Columbian cities built pyramidal platforms of cut stone. El Castillo (Chichén Itzá) consists of square terraces with 91 steps on each side (365 steps in total) leading to a temple that emphasizes vertical scale. These stepped pyramids lack true arches, instead relying on cornice vaults in the inner chambers.

- Mesopotamian ziggurats In Sumerian/Babylonian cities, ziggurats served as elevated temple bases. They are stepped pyramids (flat-topped) built of mudbrick and glazed brick, often crowned by a temple. Later Persian palaces (e.g. Persepolis) also showed the continuation of colonnaded halls, using tall stone columns in the hypostyle halls.

- Roman arches Roman engineering revolutionized large-scale construction by introducing true arches, domes and concrete (e.g. aqueducts, Pantheon) – an improvement on earlier forms.

The Egyptian columns in the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak (Luxor) are carved and painted to resemble lotus and papyrus stems. These massive stone pillars demonstrate Egyptian mastery of the pillar and lintel system for monumental temples.

Environmental Considerations

Architects often oriented and shaped buildings according to the local climate. In hot and arid regions, ancient builders used thick walls and small windows to minimize heat gain. Sumerian houses in Mesopotamia, for example, were grouped closely (sharing walls) with central courtyards for light and ventilation. The Egyptians built houses of adobe and stone in the same way: the houses of the rich had shaded courtyards and even sleeping terraces on the roofs to take advantage of the night breezes (cooler at night). They also invented wind catchers (malakaf) – tall chimney-like towers with openings facing the prevailing wind – to direct air into buildings and expel hot air out. This type of passive cooling is a hallmark of sustainable design. Important buildings in Mayan cities are astronomically aligned: El Castillo’s staircase casts a serrated snake shadow at the equinox, showing the integration of solar pathways. Indus Valley cities like Mohenjo-daro had paved streets and sewers; houses had private wells and toilets that drained into covered brick sewers. They also built high city walls that doubled as flood barriers against seasonal rivers.

- Sumerian/Mesopotamian design: Thick earthen walls and limited openings kept interiors cooler. Adobe houses were often adjacent to each other, reducing the wall area exposed to the sun; narrow shaded streets provided relief.

- Egyptian coolness: Dwellings utilized courtyards and roof spaces; more importantly, “mulkaf” wind towers directed breezes into rooms. For large temples, the Egyptians aligned buildings according to celestial events (solstices/equinoxes) that required precise sight lines, as at Karnak.

- Indus Valley planning: Urban networks at Harappa and Mohenjo-daro optimized sunlight and sanitation. Many houses had northern baths and sewers; wastewater was diverted to street drains. City walls provided protection against monsoon floods.

- Maya alignments: Temples and plazas often follow cardinal or astronomical orientations. Chichén Itzá’s El Castillo is rotated so that the equinox sun angles create the famous snake-shadow effect. This shows that solar pathways were deliberately integrated into the design.

- Greek towns: Mediterranean towns often have narrow winding streets and houses with courtyards to provide shade and catch the sea breezes (as seen in many traditional Greek villages).

A cluster of wind towers (badgīr) in Yazd, Iran. These traditional chimneys capture prevailing breezes and direct them into buildings for passive cooling, an ancient technique still effective in desert climates.

Psychological Aspects

Monumentality and symbolism often drove architectural form. To impress their subjects and the gods, rulers built massive structures reflecting a “larger than life” mentality. The Egyptian pyramids and temple pillars are the most famous: huge stone structures with almost no openings, emphasizing solidity and permanence. In Mesopotamia, large gates and protective figures signified power. For example, ziggurats (stepped temples) rose above cities as visible landmarks and became “monuments to local religions”. Assyrian and Babylonian cities placed huge lamassu (winged bull-human) statues at the palace gates – huge apotropaic guardians surrounding the entrances. Such elements were meant to frighten and even intimidate visitors. Similarly, Greek city-states built imposing temples (e.g. the Parthenon) and theaters as expressions of civic pride, but their style emphasized harmony as much as grandeur. In the Americas, Mayan and Inca rulers also signaled social hierarchy by building towering pyramids and plazas for ritual displays (the height of El Castillo, for example, symbolized the ascension of Kukulkán).

- Egyptian monuments: The pyramids and temple complexes of the pharaohs exhibit a gigantic scale. All the great temples used pillars and lintels of stone beams on massive columns, a heavy, unyielding style designed for durability. The effect was awe-inspiring for worshippers and subjects alike.

- Mesopotamian towers and gates: Ziggurats (e.g. Ur) were huge stepped towers that literally brought the temple closer to heaven. City gates (such as Babylon’s Ishtar Gate, seen below) were richly decorated and flanked by towering statues. The gates of Assyrian palaces were lined with stone lamassus (huge multi-legged guardian figures) reflecting power and divine protection.

- Greek/Persian: While Greek temples were often more elegant than imposing, they nevertheless served as symbols of the prestige of the city-state. Persian Persepolis used forests of columns to create an overwhelming sense of grandeur in its reception halls.

- Mesoamerican temples: Mayan and later Aztec pyramids rose above plazas. Stepped temples (with high platforms) were conceived as bridges to the gods and indicators of the ruler’s divine favor. The height and scale of structures such as Tikal’s Temple IV or Chichén Itzá signified ritual significance.

Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate of Babylon (c. 575 BC) in the Pergamon Museum. The blue glazed brick gate with stylized lions is an example of Mesopotamian monumental design – blending art with sheer scale to amaze onlookers and demonstrate royal power.

Human Centered and Sustainable Design

Even in ancient times, some societies prioritized comfort, efficiency and social utility in their architecture. Harappa houses in the Indus civilization had private bathing rooms and indoor drainage; a jar of water could flow through brick pipes into the city sewer to flush toilets. Most houses had separate wells that provided a reliable water supply. Egyptians similarly utilized local resources: residential structures were built with sun-dried adobe and stone to buffer heat, and wealthier houses had decorative gardens (pleasure gardens with pools) for shade and irrigation. More importantly, Egyptians slept on roof terraces in summer to cool off with night breezes. Middle Eastern architects developed these principles further: as mentioned above, windbreaks and evaporative ponds provided passive climate control. Even Greek urban planners designed compact housing blocks with communal courtyards (providing social space and ventilation). In sum, many ancient communities were built with people’s daily needs in mind, from sanitation (Indus) to natural ventilation (Egypt, Iran) to urban livability.

- Indus Valley sanitation: Cities like Mohenjo-daro pioneered indoor plumbing. Houses typically had latrines and “private” toilets. Waste was transported by gravity-fed drains made of uniform bricks, a remarkable early sewage system.

- Cooling and living comfort of the Egyptians: Dwellings were often organized around inner courtyards and roof terraces. The famous mulkaf (wind tower) was a human-centered innovation: it drew fresh air into living spaces. In summer, it was common to sleep outdoors on flat roofs for natural cooling.

- Courtyard houses (Mediterranean/Asian): Many houses in the ancient world were clustered around open courtyards to maximize daylight and airflow. (For example, traditional Greek and Chinese courtyard houses later formalized these ideas, but they date to post-ancient times).

- Resource efficiency: Early architects often minimized resource waste by using local materials (adobe in Mesopotamia and Egypt, stone in mountainous regions, timber in forests) and machine-free designs. The emphasis on passive climate strategies (see Environment section) is an early form of sustainable design.

Impact of Wildlife Habitat

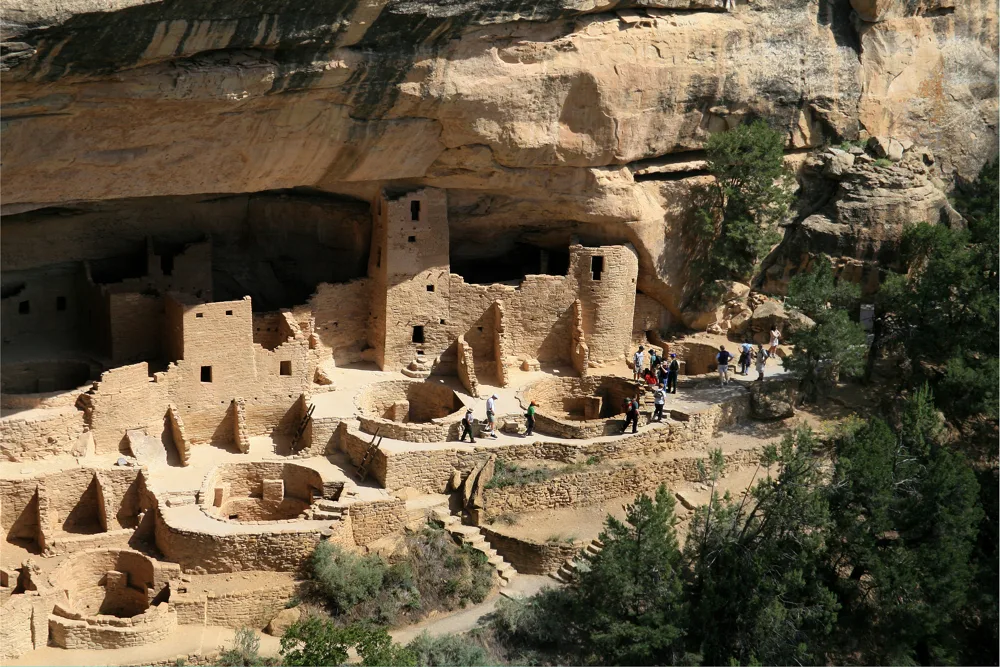

Architectural form often adapted to the natural landscape. In flood-prone areas such as the Indus, cities were built on mounds and surrounded by high walls, which served both defensive and flood control purposes. Similarly, Egyptian settlements rose above the Nile floodplain. Mountainous and cliff regions inspired settled dwellings. For example, the Ancestral Puebloans of Mesa Verde built the Cliff Palace (c. 1200 AD) beneath a natural hollow in the canyon wall. This 150-room village (housing ~100 people) was sheltered by an overhanging cliff using sandstone blocks and timber, blending architecture with its rocky habitat. In Mesoamerica, mountainous Mayan cities (such as Copán and Tikal) oriented terraces towards the slopes. In South America, the Incas built Machu Picchu and other cities on steep ridges, carving terraces and stone walls to match the Andes. Even on islands or lakes, ancient peoples shaped their settlements according to the terrain (for example, the temples of Lake Titicaca on raised islands). In general, nature determined much of the design, from the materials used (adobe in deserts, wood in forests) to the orientation of the building (for example, the Greek hill temples at Delphi or Olympus followed the contours of the mountains).

- Indus flood defenses: The great Harappan cities had fortress mounds and massive perimeter walls. Archaeological evidence suggests that these city walls also served as a barrier against monsoon floods.

- Cliff Palace (Mesa Verde): Built around 1200 CE under an overhanging cliff in present-day Colorado, the Cliff Palace contained ~150 rooms and 23 ritual kivas. The Puebloans quarried the sandstone blocks in situ and placed them in the natural hollow of the cliff, providing protection from the weather.

- River and lakeside architecture: Many early temples and cities were located near water for resources and transportation (e.g. Egyptian and Mesopotamian cities on rivers; Mesoamerican temple-pyramids near cenotes or springs). Builders often incorporated water into the design (baths, pools) and oriented structures to prevailing breezes over the water.

- Hill and mountain sites: The Acropolis (Athens) and Mesa Verde are two extremes of adaptation to altitude. The Inca citadel of Machu Picchu similarly shows how terraces and stonework were used to stabilize steep slopes. In each case, the architects let the landscape guide the plan.

The Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde (Colorado, c. 1200 AD) is located under a sandstone ledge. Built into hollows, this Ancestral Puebloan village used local stone and followed the natural ledge – a clear example of architecture shaped by the wild environment.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.