Modern homes and apartments move us almost seamlessly from one space to another, leaving little room to breathe. The once-familiar corridor—that narrow, confining channel between rooms—is shrinking or disappearing entirely from many floor plans. Home builders are avoiding what they see as wasted space in non-functional areas like hallways, instead touting the efficiency gains of arranging functional rooms in a “Tetris”-like configuration. Today, when you step through the front door of a newly built building, you will likely find yourself in the living room or kitchen without passing through any foyer or hallway. This design trend reflects a cultural mindset that rewards openness, speed, and the utilitarian use of space. However, while celebrating the open-plan lifestyle, we may be mourning an architectural and emotional loss. The humble corridor—that in-between space, the transition area—has quietly served important purposes in our homes and our souls. Its disappearance raises questions: What was the corridor originally for, and what happens when we remove it? How does losing these thresholds affect our sense of privacy, comfort, and ritual within the home? And what does this erasure say about our cultural relationship with space, time, and attention?

What was the corridor originally designed for, and what happens when we remove it?

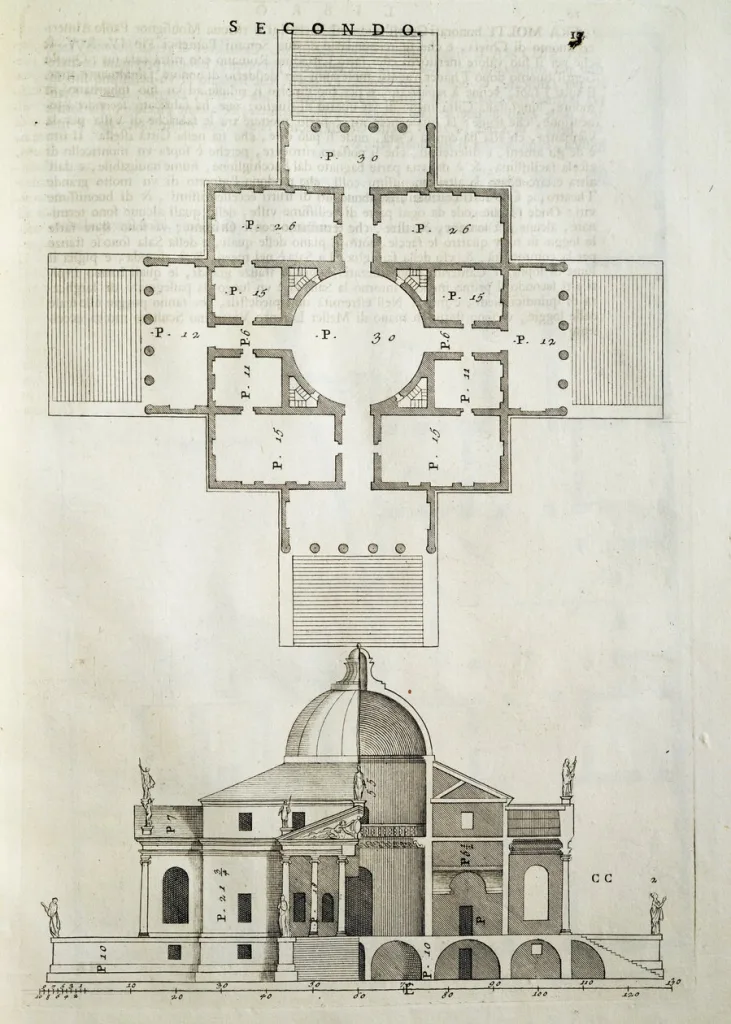

Before the era of open-plan living, corridors and similar passageways developed to meet basic functional and social needs in buildings. The corridor as we know it today has a relatively recent origin in architectural history. In many pre-modern residences, there were no separate corridors—movement flowed directly from rooms or multi-purpose halls. For example, Renaissance Italian villas featured enfilades of interconnected rooms without private passageways. Andrea Palladio’s Villa Rotunda (circa 1570) is a classic example of a plan where “the path through a house is indistinguishable from the occupied parts of a house.”

People could move around the dwelling in multiple directions, paths could intersect freely, and privacy was managed through social protocols rather than physical divisions. This meant a permeable living arrangement: residents frequently encountered each other, and spaces served overlapping functions. Similarly, in many non-Western traditional homes, a central hall or courtyard served as both a circulation and living space. For example, the Ottoman-Turkish house was typically built around a sofa or hayat – a large hall connecting the rooms. These were not just corridors, but rather “multi-purpose halls between rooms” that were often used for sitting, working, or receiving guests. In such houses, the rooms were largely self-contained and opened onto the sofa; the sofa itself was an open, transitional area that allowed for airflow, light, and social interaction.

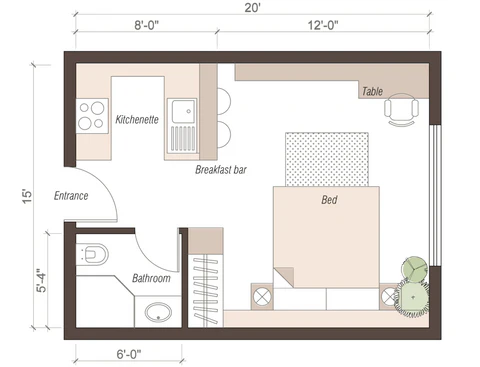

The plan of a Renaissance villa (Palladio’s Villa Rotunda) features en-suite connected rooms without separate corridors. Such layouts offered numerous paths and frequently intersecting traffic areas.

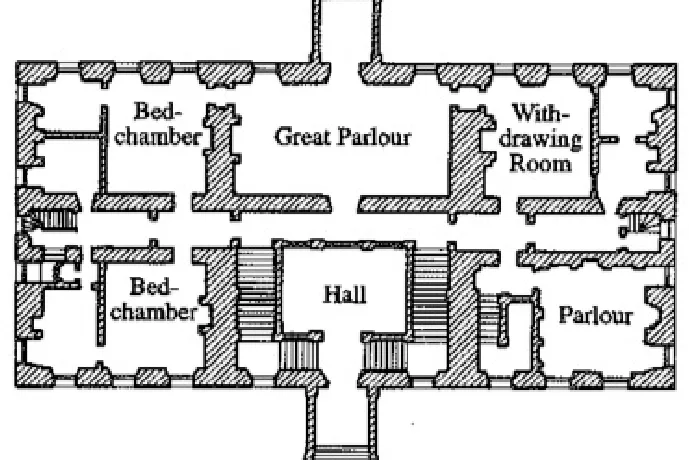

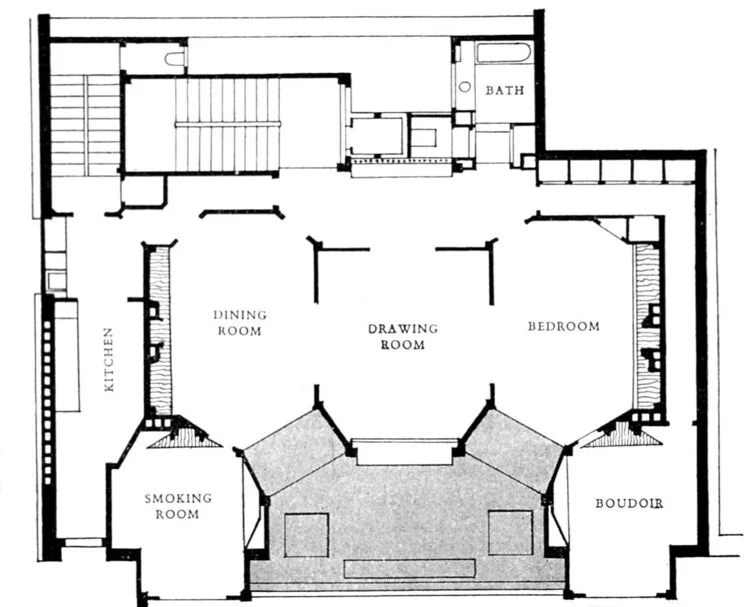

Early corridor plan of Coleshill House (17th–19th centuries), an English country house (highlighted in the center). The addition of a corridor allowed circulation between rooms without interfering with private areas.

The corridor did not become a standard feature of Western domestic architecture until the 18th and 19th centuries. Social historians and theorists such as Robin Evans have mapped this change: as lifestyles began to value individual privacy, regular circulation, and the separation of domestic functions, internal passageways were used to “separate people and activities” within a house. In Victorian England, corridors allowed family members and servants to move around shared rooms without constantly disturbing one another. Evans sarcastically notes that by the 1800s, “the only purpose of the corridor was to prevent people from disturbing one another”—the corridor helped solve this problem by keeping traffic in its own lane. At its core, the corridor was designed as a buffer and regulator. It was a neutral zone that gave each main room a kind of autonomy: activities in the living room, bedroom, and study could remain separate, while the corridor handled entry and exit. This functional logic extended to institutions like schools and hospitals, where long corridors efficiently connected many rooms, and to apartment buildings, where corridors maximized access within a narrow footprint.

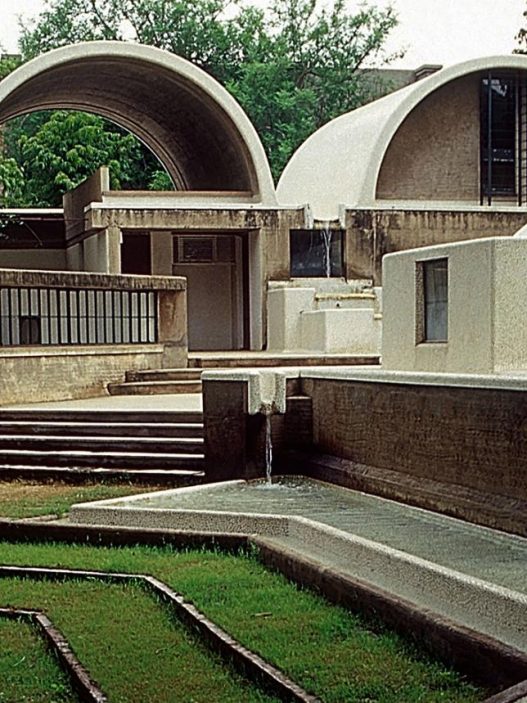

Beyond efficiency, corridors have historically served a subtle psychological function: they provide a decompression zone between different environments. Stepping from the intense silence of a library into a corridor or from the privacy of a bedroom into a living room, one experiences a brief mental reset. In early homes, entrance halls or galleries were often found not only for practical purposes (removing coats, greeting visitors) but also to provide a moment of transition from the outside world to the inner sacred space. In monasteries, the cloister, a roofed passageway surrounding a courtyard, was the spiritual cousin of the corridor, offering a sheltered, rhythmic space for contemplation between the chapel, refectory, and cells. The monastery’s long corridors buffered the noise of the world and prepared the mind for prayer. Similarly, the Ottoman house’s sofa served as a threshold between the public reception room and the private family quarters—a spatial threshold where one could symbolically “leave the outside behind” before entering the deeper private realm.

So what happens when we remove the corridor? Practically speaking, we gain a few extra square meters of usable space—a larger living room or kitchen extension where the corridor would have been. This is one of the main reasons developers are starting to eliminate corridors; in contemporary home design, any space that doesn’t directly “add value” to living or storage tends to be seen as unnecessary. As a residential research group has clearly stated, today designers are combining rooms by “eliminating unnecessary circulation space” to reduce overall home size at an affordable cost. The result is an open-plan layout with fewer interior walls and functional zones directly adjacent to one another. However, this efficiency comes at the expense of spatial hierarchy and breathing space. Without corridors, movement is immediate and disorienting: one steps out of a bedroom and is immediately immersed in the noise of the living area or enters the core of the house directly from outside. There is no transition or soft progression from public to private spaces. Architecturally, the home is no longer a series of distinct rooms connected by neutral passageways but rather an uninterrupted environment divided into zones. We lose the buffer that once absorbed sound, sight, and even scent between rooms. The psychological “airlock” provided by a corridor—a moment to gather oneself when transitioning from one context to another—is gone. At its core, the modern open layout trades the ritual of transition for an instantaneous experience. This can be liberating and social, as we will discover, but it also has profound effects on privacy, sensory comfort, and the way we experience our homes.

How Does the Absence of Corridors Affect Spatial Privacy and Perception of Boundaries in Homes?

One of the most immediate effects of a corridor-free, open-plan home is on privacy – both physical and psychological. In the traditional layout, corridors and doors allowed for clear divisions: you could close the bedroom door and be “away” from the kitchen and living room, which were separated by the corridor and the walls between them. Each room was a kind of sanctuary, and the hallway served as a moat. In open-plan designs, these moats dry up. The boundaries between functional areas are blurred or invisible, which means a shrinking sense of personal space. Everything is actually in the same large room, and at best there are partial clues separating the areas. This can lead to a constant feeling of exposure. Family members or roommates are always within each other’s field of vision (or hearing), even if they are engaged in different activities. A parent trying to work or read in one corner of the large room can see and hear children playing in the kitchen area and a television blaring in the “media corner,” because everything is in a single stream. The lack of partitions makes it difficult to escape mentally from distractions or to be alone. “One of the most obvious disadvantages of an open layout is the lack of private space”. People may start to miss walls without realizing why—until they find themselves hiding in the bathroom to be alone for a moment, because it’s the only door that closes.

Open layouts also affect comfort and cognitive load by increasing noise and stimuli. Since there are no corridors or solid barriers, sound spreads uncontrolled. The clatter of dishes in the kitchen, video games in the living area, phone conversations next to the desk—all contribute to a single sound environment. Real estate experts say, “Open spaces can increase noise, making them challenging for families with children or people who work from home.” Constant background noise can raise stress and frustration levels, much like in open-plan offices. Visually, everything is in plain sight. With no hallway or door to hide behind, any clutter or activity in one area is visible from another. This constant visual field can be overwhelming—there is nowhere for the eyes or mind to rest. In fact, organizers report that without walls or defined areas to hide or organize items, open floor plans can lead to “visual clutter becoming overwhelming and creating a feeling of overstimulation.” The brain is required to process multiple micro-environments simultaneously, and there is no intermediate “blank” space (such as a neutral corridor wall) to provide a reset. Interior designer Natalie Aldridge mentions that in open-concept homes, “seeing half the house at a glance” can be exhausting—especially if that view includes cluttered countertops or toys scattered around.

For residents, the difficulty of setting boundaries in such spaces can affect behavior and well-being. Many people find it difficult to relax when they feel “on display” or lack a place to retreat to. In an open-plan home, even when you’re alone, the spaciousness can feel psychologically overwhelming—the opposite of comfort. And when others are around, the absence of anything separating you can create a subtle pressure to be ready or on guard. This is especially true for children, the elderly, and neurodivergent individuals who need environmental cues and separation to feel safe. Young children living in a completely open home may have trouble napping or focusing because sounds and movements permeate everywhere. They also lose the advantage of a quiet corner or a door that can be closed while studying, which can potentially affect concentration. For the elderly or those with cognitive challenges, open layouts can be confusing—without clear rooms or hallways, it may be more difficult to create a mental map of the home or interpret the purpose of each space. (In memory care design, there is debate about open layouts: while they offer visual access, some studies suggest that the lack of defined or closed spaces may contribute to disorientation in people with dementia.)

More importantly, individuals who are sensitive to sensory input—such as many people on the autism spectrum or with ADHD—may find open-plan living overwhelming. The constant flow of stimuli and lack of a quiet space can increase anxiety or trigger sensory overload. They may prefer a small, enclosed space to regulate their emotions; classic hallways or corners often provide this. Without a permanent refuge, families may have to create temporary ones (a tent in the corner for a child who needs to rest, or noise-canceling headphones for a teenager doing homework at the dining table). Privacy is not just about hiding from others; it is about having control over one’s environment. The removal of corridors often means a loss of control over exposure. In the words of an organizational expert, “without walls or clear divisions, some people struggle to create a sense of intimacy or mentally ‘switch off’ in their homes.”

This situation became particularly apparent during the recent pandemic, when homes were transformed into multipurpose spaces 24/7. Families suddenly found it difficult to have multiple activities (work meetings, remote learning, relaxation) coexist in one large open space without conflict. As a result, many people began to long for walls, doors, or anything else that would bring back some sense of separation.

So it’s hardly surprising that there has been a mini backlash. Designers and homeowners are rediscovering the value of thresholds and separate rooms for well-being. Surveys indicate a growing desire for more traditional layouts or at least hybrid solutions, driven by factors such as the need for privacy, sound control, and designated spaces for different tasks. Once upon a time, open-plan homes assumed that corridors eliminated personal space, but now they must mimic this effect through furniture arrangements or screens (a trend we’ll explore in the next section). The psychological result is that people benefit from zoning—different areas for different moods and lifestyles. Corridors once served as the seams that connected these zones while keeping them separate. Without these seams, our indoor spaces risk becoming a homogenized blur, which can subtly erode the sense of sanctuary and order that a home should provide.

Can Corridor-Like Passageways Enhance Emotional Narrative and Ritual in Everyday Life?

Architectural spaces do not merely fulfill practical needs; they also contribute to the emotional fabric of our daily experiences. A corridor, though often simple and utilitarian, has long played a role in the narrative of movement within a space by offering moments of pause, anticipation, or reflection as one transitions from one place to another. The philosopher Gaston Bachelard, in his classic work The Poetics of Space, reminds us that such thresholds and “in-between” spaces are rich in imaginary and emotional meaning. “Both the outside and the inside are private spaces… If there is a surface at the boundary between such an inside and an outside, this surface causes pain on both sides,” he writes. Bachelard implies the loaded nature of the threshold: the doorway or corridor where one stands between the familiar and the unknown, the private and the public. It is a zone of uncertainty—a liminal region—and as such, it can heighten our awareness. We have all felt that slight excitement when waiting in the entrance hall before entering an important room or walking down a quiet corridor after a noisy meeting. The corridor can be a buffer that allows us to shift gears and roles not only physically but also emotionally.

Consider a simple homecoming ritual. In cultures around the world, there is an entranceway where the outside world is symbolically left behind. In Japan, this is the genkan, an entranceway where one removes their shoes and mentally “leaves the outside world behind.” The genkan is not merely a practical mudroom; it serves as a threshold between the ordinary world and the inner sacred space of the home (a concept derived from Zen monastery architecture), resonating deeply with cultural significance. Stepping into the genkan from outside in slippers instead of shoes is a small but meaningful ritual—a way of saying, “I am now entering a protected, sacred space.” In traditional Japanese inns (ryokan), corridors are typically dimly lit, covered in tatami mats, and punctuated by the soft padding of slippered feet. At the threshold, a neatly arranged row of shoes may be visible; each pair represents a traveler’s transition from journey to restful lodging. These corridors become both metaphorical and literal bridges. When you reach your room, you find yourself psychologically removed from the outside world. When homes eliminate entry halls or foyers, we lose part of this ritual. Walking directly into a living room where the TV is on and dinner is on the stove means there is no gentle mental ramp—you immediately enter the intensity of domestic demands without the chance to gently “arrive.”

Corridors and passageways also allow for moments of narrative in spatial journeys. Think of a long hospital corridor and how each step toward a patient’s room can increase your anxiety or hope—in this case, the corridor is a place to gather courage or calm. Or consider the cliché but meaningful scene of a child sent to stand in the hallway for misbehaving in class: the hallway, being neither here nor there, semi-public yet separate, becomes a place of penance and reflection. In homes, a hallway can similarly frame our experiences. In the morning, walking down a hallway toward the kitchen, each family photo on the wall can greet you with a memory, fully waking you up. At night, the same hallway, dimly lit, can create a sense of silence, preparing you for sleep as you leave the living areas and head toward the bedrooms. Architectural theorist Juhani Pallasmaa has emphasized how such sensory cues affect us—lighting, acoustics, and even changes in floor texture in a transitional space can signal a new mood in the subconscious. A carpeted corridor that follows a bright and noisy living room immediately softens the atmosphere and pushes you toward silence. Without a corridor, we cannot allow the day’s noise to gradually fade away; the change can only be sudden.

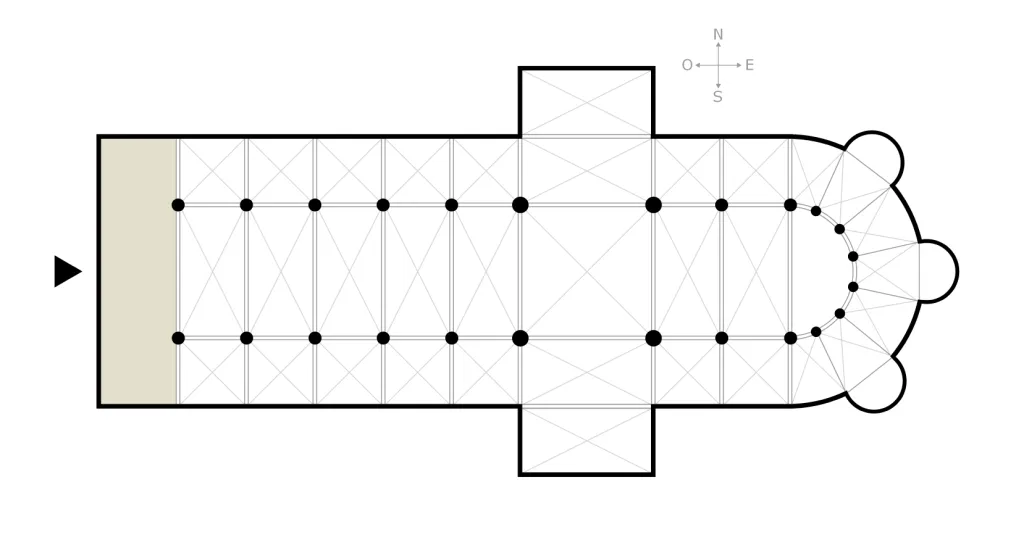

Furthermore, transition areas are historically filled with ceremony and symbolism. In religious and monumental architecture, passageways often represent spiritual progress. The narthex (entrance hall) of a cathedral prepares worshippers to enter the nave, just as the cloister of a monastery prepares monks to re-enter the chapel. Even in local architecture, thresholds have meaning—think of how many cultures have superstitions or traditions related to entering a home (from bringing the bride over the threshold to rituals for moving into a new home that include the foyer). These traditions implicitly recognize the threshold as a special area. When architecture compresses or erases these spaces, some of the poetry of daily life can be lost. We may perform fewer small rituals, such as pausing at an entry desk to leave our keys and mentally close the day, lingering on a landing to say goodbye, or passing through a winding corridor that builds anticipation before revealing a large room. The “emotional narrative” of moving through a home becomes flatter—in an open plan, every space announces itself at once, leaving less to discover or savor slowly.

Transition areas also allow for moments of solitude and reflection within a shared space. Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, known for his sensory approach, writes about the importance of thresholds and intermediate spaces in creating atmosphere. Zumthor often designs buildings with layers—an outer courtyard, a low-lit entrance, a vestibule-like corridor—so that entering the main space becomes a kind of journey of initiation. He argues that these intermediate layers set the emotional tone and allow visitors to adjust their “frequency” to that of the building. In everyday homes, a corridor can serve a similar purpose on a smaller scale: a place where a family member can walk for even 10 seconds between the chaos of the kitchen and the privacy of the bedroom and gather their thoughts. It can be said that people often walk in corridors when they are anxious or thinking; the linear, neutral space makes it easier to take a meditative step, unlike the cluttered living room. Indeed, a writer has described a hallway as “a place that carries you from one place to another, holds you while you rest, think, and meditate, cutting off the noise around you.” Without corridors, where could we step or retreat to find a moment of peace within the house? Instead, we might find ourselves circling around a kitchen island—but we wouldn’t capture the same thoughtful atmosphere!

Modern düzenler, geçişleri sıkıştırarak fırsat ve ritüel duygumuzu da sıkıştırabilir. Her yemek, televizyon izlediğiniz ve ev ödevlerinizi yaptığınız aynı açık büyük odada yenildiğinde, bir koridor üzerinden farklı bir yemek odasına geçme eylemi (zihniyette bir değişime izin verebilirdi – “şimdi akşam yemeği için toplanıyoruz”) yok olur. Sonuç, hayatın bir dizi amaçlı an yerine sürekli bir çoklu görev olduğu hissi olabilir. Elbette açık alanlarda hala ritüeller geliştirilebilir, ancak mimari bunları pekiştirmiyor. Bunun yerine, her şey paradoksal bir şekilde mahrem anların özelliğini azaltabilecek çıplak bir mahremiyet içinde açığa çıkıyor.

This does not mean that corridors are magical or that open plans cannot be spiritual. Many modern architects have attempted to create new types of transition experiences without traditional corridors. Some, such as Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto, blur the boundaries so much that the entire house becomes a continuous transition ( Fujimoto‘s N House is made up of “interlocking shells” — layers of enclosures extending from the exterior to the interior — effectively transforming the entire residence into an extended threshold). In such designs, the transition ritual is still present, but in a new form: instead of a separate corridor, you pass through semi-open areas, courtyards, and intermediate spaces, with each step providing a subtle transition in light and privacy. This demonstrates that what people are seeking is not a narrow corridor, but rather a “transition experience”—an experiential buffer and narrative between points A and B. If we were to remove it, we would have to ask: are we replacing this experience with something else, or are we simply giving it up?

Koridorun Yerini Ne Aldı ve Bu İkameler Psikolojik ve Mimari Açıdan Yeterli mi?

As corridors and formal entrances disappeared from many floor plans, architects and building occupants developed improvised substitutes to fulfill some of the same functions. We haven’t completely abandoned the idea of defining space—we’re just doing it with different tools. A common strategy in open-plan interiors is the use of visual zoning elements: material, level, or layout changes that suggest a boundary without a wall. For example, a change in floor covering (tiles in the kitchen, hardwood in the living area) can signal a transition from one function to another. Area rugs are a popular and easy tool—a large rug placed under a sofa and coffee table creates an “island” that mentally separates the seating/living area from the adjacent dining area. Similarly, a drop or suspended ceiling installed above the kitchen can give the impression of a closed-off space within a larger room. These design moves function as “invisible walls” or symbolic corridors. They subtly guide the eye and movement: you may instinctively walk along the edge of the rug or align yourself with a ceiling beam as if following an invisible corridor.

Furniture placement also plays an important role in open floor plans. A strategically placed sofa or bookcase can serve as a low partition that defines a path. For example, placing a sofa in the center of the room, with its back facing the dining area, not only defines the living space but also creates a mini “passageway” behind it, allowing access from the entrance to the rest of the house. Essentially, the back of the sofa becomes a stand-in for a corridor wall. Open shelves or curtain dividers are even more open—they provide partial visual blocking while allowing light and conversation to pass through. It is telling that interior design advice columns now frequently recommend using bookcases, curtains, or folding screens to create privacy or separation in open-plan homes. These elements hark back to the folding room dividers of past centuries, a revived idea adapted to address new challenges. In a way, these are movable corridors—flexible partitions that can be used when needed. Do they work? To a certain extent, yes: they can provide a sense of enclosure or at least create a backdrop that helps focus on an area. However, they rarely provide the full acoustic or visual separation that a real corridor and door can offer. A curtain drawn across the sleeping area of a studio apartment is still a thin veil; sound and light seep through, and the person’s awareness of the wider space persists.

Another method that can be used instead of a corridor is strategic room arrangement without actual corridors. Contemporary architects often design houses where rooms flow into one another, but with careful attention to their arrangement. For example, instead of entering the living room directly, you can enter a small foyer corner that is visually open to the living room but separated by a short partition or even an independent coat rack and bench. This foyer can then “lead” to the large room by mimicking the open progression of an entrance hall. Architects refer to this as creating an “implicit threshold.” It’s somewhat akin to having a veranda within the house—a temporary point that belongs neither outside nor inside. Material changes often reinforce this: a different ceiling treatment in the foyer corner or a pendant light creating a smaller volume within the larger space.

We also see designers experimenting with half walls or interior windows that maintain sight lines but provide a sense of physical boundaries. A half wall at waist height can separate an entrance or work area without extending all the way to the ceiling. Glass partitions or interior windows (e.g., a kitchen that is mostly open but has a half-glass wall above the counter) can maintain visual openness while reducing noise and odor transfer. There is also the concept of a “broken plan,” which emerged in design circles as a term opposed to the completely open plan. A fragmented plan layout uses elements such as stepped floor levels, partial dividers, and varying ceiling heights to create loosely connected different areas. Imagine a home where the living room is a few steps below the kitchen and partially surrounded by a waist-high wall; you still feel like you’re part of a single space, but the changes in level and enclosure give each area a distinct ambiance. These are creative endeavors aimed at having the best of both worlds: some openness and connection, but also articulated separation.

Perhaps the most technologically advanced substitutes are acoustic solutions. Since one of the biggest losses resulting from the removal of corridors is sound absorption, some modern homes (especially luxury ones) are investing in sound-absorbing materials or construction tricks to compensate for this. For example, using extra insulation in interior partitions or adding acoustic panels that look like decor but soften noise. As a design vice president noted, some builders are balancing the lack of a living room by “placing a closet between two bedrooms” or using other adjacent sound-dampening elements. However, such measures are still relatively rare in multi-unit housing—sound insulation is typically subject to value engineering. As a result, many open-plan residents turn to behavioral solutions: noise-canceling headphones, white noise machines in bedrooms, or simply “quiet hours” rules—human-made temporary fixes for an architectural shortcoming.

An intriguing question is whether these substitutes fulfill the psychological role of a corridor. Visually, we can certainly fool the eye into perceiving different areas; intellectually, we know that a rug or a divider means “this area is separate.” But do we intuitively feel the same benefit? For partial cues like rugs and furniture, the effect may be limited. They do little to prevent sensory overload or provide real privacy—they are more like suggestions of boundaries than actual boundaries. We can compare this to open-office partitions: even with low partitions, you know you’re in a sea of people and privacy is nominal. However, some techniques, such as lighting or level changes, can create a strong psychological boundary. For example, stepping into a sunken living room can really feel like entering a different area (even if there is no door). People are highly sensitive to spatial transitions—a small threshold or framed opening can convey a lot. Therefore, a wide door or archway between rooms can sometimes amplify the sense of crossing a threshold, even if it is transparent.

Some modern designs are likely going even further by creating entirely new types of transition areas. We mentioned Sou Fujimoto’s N House earlier: instead of corridors, this house consists of interlocking enclosures and courtyards, creating a gradual transition between interior and exterior spaces. In such a house, as Fujimoto puts it, “there is no distinct boundary other than the gradual change in space.” The entire space consists of a seamless transition, yet achieves comfort through layering. This demonstrates that it is possible to reimagine the corridor not as a narrow tube but as a series of overlapping zones that soften the transition from one space to another. Some contemporary buildings incorporate closed courtyards or atriums that act like large halls, connecting rooms while also separating them along a void. Others use open-air corridors (common in some tropical architectures): an enclosed open-air passageway that connects rooms throughout a house, essentially moving the corridor function to the exterior. These solutions can be pleasant and effective in certain contexts by providing light, air, and a sense of movement.

Still, for an average home with limited space and budget, changes tend to be simpler: the open concept itself, perhaps a few subtle adjustments like an entryway furniture set or a sliding barn door that can occasionally close off an area. Is this enough? In terms of pure functionality, it is usually sufficient. Families learn to adapt their behavior to open living, and many enjoy the flexibility (let’s not forget that open-plan design has gained popularity because many people find traditional layouts too restrictive or isolating). Being able to cook and chat with someone in the living room at the same time, or easily keep an eye on the children from anywhere, is nice. These are real advantages that are not hindered by rugs and furniture. However, where substitutes fall short is in providing solid options for retreat and focus. A curtain or a bookshelf cannot replicate the reassuring click of a door closing off the world or the solidity of a wall that guarantees you won’t be seen. These are half-measures.

There is also an aesthetic and symbolic aspect. Some architects lament that by removing corridors, we lose opportunities for spatial drama and progression. A well-designed corridor can create tension or reveal views gradually (think of a long corridor ending in a window framing a tree, a small moment of art). Niches for a beloved library or a place to display works of art can be found in corridors—serving as a gallery of personal memories. Open-plan homes trying to replace corridors may attempt to replicate this feeling by surrounding a large room with storage or decor. However, an open room tends to focus on the big picture, while corridors celebrate the peripheral and sequential. Perhaps one reason people feel something is “missing” in very minimal open spaces is the absence of a sense of progression, the lack of waypoints in the home’s geography.

In summary, the alternatives used in place of corridors—carpets, furniture arrangements, half walls, level changes, and the like—mitigate the loss but do not fully compensate for it. They help to restore some visual order and a sense of space by assisting the perception of boundaries. However, they generally perform below par in terms of acoustics and psychology. Apart from a few innovative designs, the functionality of most open-plan homes relies on the tolerance and adaptability of the building’s occupants. In conclusion, we see a pattern: many residents eventually introduce post-sale adjustments (curtains, room dividers, additional doors) after living in a completely open space for some time. This is akin to adding a comma to a run-on sentence—the human mind craves a bit of punctuation in the home’s continuous space.

What does the erasure of the corridor reveal about our cultural relationship with space, time, and attention?

The disappearance of corridors in modern homes is more than just a quirk of architectural fashion; it is a physical reflection of deeper cultural changes in the value we place on space and the way we manage time and attention. In a way, our floor plans have become a mirror of contemporary life: fluid, efficient, and always “open.” What does the fact that we have designed spaces by eliminating intermediate areas, pauses, and buffers say about us? Several themes emerge.

First, the loss of corridors highlights our obsession with efficiency and maximization. We live in an age where value is often measured in quantitative terms—square footage, cost per square foot, functional benefit. By these measures, a corridor is “wasted space” because it is not a destination room and is not typically counted in lifestyle features. Designers can promote more open and usable space in a compact area by squeezing corridors. Culturally, this aligns with a broader notion that empty space (or free time) is undesirable. Just as we fill our calendars with productivity hacks and constant connectivity, we have filled our homes with constant functionality. Every corner must have a purpose (a work corner, a storage unit, etc.), just as we feel compelled to check emails or scroll through feeds every minute. The disappearance of the hallway is the spatial equivalent of our reluctance to let even a moment go to waste. We’ve lost some of our appreciation for negative space, for breathing room, not just in architecture but in our lifestyles as well. This points to a cultural momentum: faster lives demand that our environments keep pace.

In addition, the open-plan, corridor-free trend reflects a shift in values away from privacy and formality toward transparency and collectivity. In the mid-20th century, modernists such as Frank Lloyd Wright advocated open living spaces as a way to bring families together and break down the rigid boundaries of Victorian homes. Society was moving toward informality, equality, and collaboration—walls (and their symbolic corridors) came down. Today, the elimination of the corridor takes this ideal to an extreme: the home as a single shared space. It suggests prioritizing togetherness and visibility—everyone shares the same large space—perhaps reflecting the ethos of sharing and publicness in the social media age. Yet this togetherness has two sides. Just as social media blurs the boundaries between public and private life, the open home blurs the boundaries between personal and shared space. By removing corridors, we could argue that we are physically revealing the collapse of the boundaries that define modern life. Work and home are blurring (especially with remote work: without a home office behind a door, one can literally work at the kitchen table amidst the flow of domestic activities). The blurring of day and night (when the TV, dining table, and work computer occupy the same line of sight, it becomes harder to signal the end of the day or the transition to leisure time).

This leads to an effect on attention and mental rhythm. In the past, hallways created a small pause—you move from one environment to another, which requires a moment of orientation. This moment can serve as a reset for attention, an invitation to refocus. Without such cues, we may find ourselves mentally “carrying” each other’s activities with us. Many people report feeling they multitask more in open-plan homes—cooking dinner while helping children with homework or glancing at a messy kitchen that needs cleaning while watching TV. The separate-room model with corridors naturally limited such overlaps: tasks and mindsets had their place. Now, however, everything is competing for our attention in a single space at the same time. This constant partial attention is a feature of our age (juggling notifications on devices, etc.), and the home environment now reinforces rather than mitigates it. It is speculative but plausible that the prevalence of open, uninterrupted spaces could be linked to a heightened sense of distraction or an inability to fully relax. Without any architectural guidance to divide activities into sections, individuals must rely entirely on mental discipline to do so.

Culturally, the disappearance of corridors also points to a changing relationship with ritual and formality. This implies that we no longer need the formal graces of transition – we are always in a hurry, always multi-tasking. The idea of the liminal moment has diminished. Anthropologically, liminal spaces (real or metaphorical) were important in rituals—they marked a person’s transition from one state to another (think of initiation ceremonies or even the time between engagement and marriage). In architecture, corridors and entrances were the boundary zones of the home. Now that these have disappeared, it can be said that we have embraced a culture of instant and constant partial interaction. We don’t “arrive” in stages; we teleport from one mode to another. Or rather, we try to exist in all modes at once. The growing interest in mindfulness and slow living may be partly due to this—we sense that something is culturally amiss and are seeking balance. Ironically, even as homes become more open and “efficient,” people have begun creating small, restorative niches: a window sill for reading, a meditation corner, or flocking to cafes for a change of scenery. These are, in a way, attempts to recreate a sense of transition or another place that the home no longer provides by default.

The disappearance of corridors also reflects how society’s values regarding privacy and community have changed. At times, we value openness (both literal openness in space and figurative openness in sharing), which leads to designs that reflect this. Then, as privacy and silence diminish, they suddenly feel like a new luxury. For example, we see news stories about technology executives banning iPads and screens at home to give their children more focused attention—always a reaction against openness. Similarly, the design pendulum may be swinging back: as people rediscover the benefits of separate rooms and closed home offices, there is talk of a “return of walls” in post-2020 home design. COVID-19 lockdowns were a social stress test for open-plan living; many people found that without the ability to escape to work or school, the lack of internal boundaries within the home became problematic. In this sense, the disappearance of hallways revealed our confidence (or arrogance) that we didn’t need boundaries—that we could handle constant togetherness and fluidity. Reevaluating this points to a cultural humility: boundaries, pauses, and transitions are healthy after all.

On a more philosophical level, the lost corridor highlights our relationship with liminality—the state of being in between. Modern Western culture is not very comfortable with liminality; we prefer clear categories and direct paths. Corridors are fundamentally liminal. Removing them could symbolize our attempts to eliminate uncertainty and empty transitions from our lives. Yet liminal spaces (and times) have value: they encourage reflection, creativity, and adaptation. Many great ideas come to us in the “corridors” of time—the walk between meetings, the commute home, the shower (often referred to as a liminal space for thinking). Without corridors in our homes and schedules, we risk losing these productive pauses. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is how our always-connected devices effectively erase the mental corridor that exists when we commute to work or spend a quiet evening—there is no transition anymore; through the internet, you are always potentially “in the same room” with everyone else. The death of the architectural corridor is an analogy for this digital collapse of transition.

The cultural relationship that emerges here is linked to how we perceive the home. Is a house (as modernists argue) a functional machine for living, where maximum efficiency and openness are ideal? Or is a house also a psychological landscape that requires texture, diversity, and even a touch of mystery? The trend of removing corridors has taken the machine paradigm too far—houses have become more like efficient attics or studio sets. But people are not machines; we desire to play a little hide-and-seek in the environments we inhabit. We see this in how popular culture romanticizes “mysterious houses” with their secret passages, or how children playing games create their own secret little rooms by draping a blanket over a table in an open space. The enduring appeal of a house with nooks and crannies suggests that there is something within us that takes pleasure in hidden places or paths that are not entirely visible. Corridors typically provide these small journeys and corners (a bench at the end of a corridor, a window halfway along). By removing them, we may have traded away part of a home’s primal capacity to enchant and comfort.

In conclusion, removing the corridor is a small design choice with significant effects. Sometimes, openness, speed, and a culture of constant activity are prioritized at the expense of introspection, privacy, and tranquility. It reflects our ambivalent desire to be connected while also needing to be separate. However, as awareness grows, there is an opportunity to consciously reintroduce limitation and pause into our built environments, whether through actual corridors or new design innovations that create this effect. The corridor may have disappeared from many homes today, but the psychological space it represents must be preserved in some way. We still need metaphorical corridors where we can slow down, prepare, think, or simply linger in time and space in order to live well. Architecture will continue to evolve alongside culture, as it always has: perhaps the next chapter will see designs that intelligently integrate transitional spaces into new forms, acknowledging that the journey from room to room (and from moment to moment) is not a waste, but a vital part of the human experience. After all, life itself is made up of transitions—and a home, like a life, is richer when it honors the in-between spaces.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.