Brutalism as an act of creating spaces with radical honesty, never promised beauty or aesthetics over purpose and goal. Its birth came from a world of chaos that fed every living soul. Governments wanted to protect their people with the simplest solutions.

One of the clearest early examples was Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation—a concrete giant in Marseille built not for luxury, but for survival. It wasn’t beautiful in a way we know. It wasn’t soft. But it offered dignity in the form of shelter, in a Europe still dusted with ash.

Designers did not want to use design as an escape from the reality of a building and began to see that its beauty actually came from its originality and character.

Alison and Peter Smithson—who helped define “New Brutalism”—believed buildings should reflect society’s raw truth. To them, stripping architecture down wasn’t minimalism. It was an act of resistance.

Brutalism fought and unearthed all the pain hidden deep beneath the wallpaper, the ornate furniture, the spacious but soulless rooms, the epic hand-drawn paintings, and the underlying falsehood.

The way a Brutalist building stands today tells us little to nothing about the original design process behind it. We need to go back and put on our post-war world glasses to truly understand what the real quest was in choosing béton brut. Named from the French béton brut, or “raw concrete”—was never about finish or perfection.

It was about exposure.

Structure on display.

Truth without surface.

When you are in a position to make decisions that affect not only yourself but millions of your followers, you must be brutally honest and even harsh in order to fulfill the mission of saving everyone from damnation.

The way Brutalist buildings meant truth and honesty, it’s pretty self-explanatory to see its getting mainstream. It was meant to protect the lives living in it while allowing people to modify it as they wish.

Brutalism wasn’t a desperate act. It was a disciplined offering. A structure built with the faith that humans would fill it with warmth.

And think it as a blank canvas with many advantages.

The European lifestyle encourages going out and spending days outdoors, whether for work, to meet friends, or to be an active member of society in a cafe or at a concert. But that logic falls apart fast—because humans don’t just need rest. We need roots. If we think of home as a place where we go to sleep and leave in the morning, we’d never have left the caves or lived in tents. Home should be a place that inspires you to get up every morning. It should inspire you to hope and believe in a better future in whatever you enjoy.

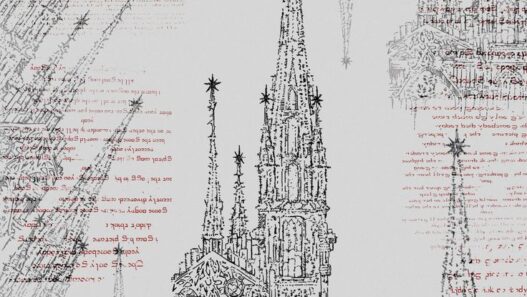

So, in a way, Brutalism gave us a cave, as if we were starting our evolution all over again, and freed us from building cathedrals. From a designer’s point of view, this may seem like an exciting opportunity to have a house designed by you for your needs. But if we take the lives of the people that day, we can clearly understand the backlash that occurred. People were on the cusp of technological innovation in a rapidly changing world. They were witnessing tens of centuries of progress in the span of a few decades. Something similar is happening with the knowledge that is being spread thanks to the Internet.

And then came the real collapse.

There was no quick way to pass on knowledge.

No blueprint.

Just millions of people living in buildings they no longer understood-

in a world they never imagined. They were lost between their childhood of the early 1900’s and the -modern – day they were living in without being able to participate.

Then came the maintenance problems and poor workmanship that began to show up in the homes of millions.

Officials ignored the dark spots. Until they couldn’t.

There was crime at the core of the building and it was starting to rot from the inside.

Nowhere this felt more than Trellick Tower in London. Designed by Ernő Goldfinger, it was once a symbol of egalitarian housing. But poor upkeep, isolation, and media sensationalism turned it into a national scapegoat.

When people realized they were living harder lives than their parents, the bitterness set in. They weren’t evolving—they were surviving inside concrete cages. That made the people riot and media to challange this idea of –suffering– to earn another day in this world.

As all the beliefs and struggles began to emerge, we saw what the real reason for the concrete choice was.

It gave us shelter.

It made humanity last longer.

She made it clear that every soul has the right to live in this cruel world.

She showed us that we can be strong but ugly. It showed us that we can be honest and simple. That life happens not in the walls themselves—but in the meals, the mourning, the moments those walls shelter.

Showed us that it is a shell to allow us to be free and hopeful inside.

All while protecting society.

Let’s look at Brutalism from today’s perspective and talk about what we’ve learned from it.

It is pretty clear that we love concrete and creating buildings that now require almost no maintenance. But as technology advances faster than ever, we started to like new more than strong.

The life we live now can be seen all over the world with similar actions. It became more mainstream and more similar without thinking about the cultural past of societies. Minimalism flourished in this context even though no one has only one set of clothes. In essence, it promotes creating multiple functions within designs, but this creates a gap between what typical end user wants and what you want. Because it dictates on how you relax, sit, sleep, create, eat, watch and use it in a single form.

Minimalism was a real search for the fact that life happens inside spaces and between people. The goal was to create a space that would allow our moments to live in silence. If we look at this direction, it’s a very similar goal to Brutalism. Both tried to be a tool, not a goal, for a satisfying life.

But somewhere along the way, both styles became aesthetics instead of tools. They were meant to serve us—yet we began serving them.

As time passed and our expectations of architecture changed, we adapted it to meet our needs. But the main search gets faded when we as humans try to satisfy a lifestyle that is not aligned with our values. What Brutalism gave us was a blank canvas to fill with our colorful lives. We should not be surprised that having a black and white life – and thinking – in a Brutalist building leads to depression. Blaming inanimate objects or walls for our dearest problems. Perhaps the main issue is not the buildings, but our lives, which are becoming standardized and one-size-fits-all, deprived of their colors and unique nuances.