Pre-Industrial Roots and Environmental Adaptation

Before the advent of factories and railways, rural homes emerged from weather conditions, soil, and customs. Builders worked with materials found under their feet and above their heads—”stone, straw, clay”—and gradually learned through trial and error to keep rooms dry, animals sheltered, and important areas warm. Roofs made of straw or reeds were not a style choice but a tool for coping with the climate, and the region’s thatched roof traditions were shaped by rainfall, wind, and harvest cycles. Today, Historic England views these local thatched roof methods as part of a place’s identity and warns that some of this knowledge is being lost.

The walls and roofs of these buildings “breathed,” harmlessly transferring moisture to the outside through lime, clay, and plant fibers. This breathability kept simple interiors mild throughout the year and protected the structure from decay. This is a lesson that conservation experts still teach when restoring old buildings. Throughout Scotland and England, guidelines for earth and clay structures emphasize understanding traditional building materials and preserving their vapor-permeable surfaces, rather than trapping moisture with modern, impermeable layers.

Adaptation also shaped the plans. In the longhouses of Dartmoor, people lived in the sloped section while cattle were housed in the lower part of the same roof; smoke from the hearth blackened the lower layers of the thatched roof, and archaeologists still study these traces to understand past crops and crafts. In the northwest, Hebridean blackhouses also shared shelter between families and animals; peat smoke passed through the thatch and stone, drying it, repelling pests, and hardening the roof. These arrangements were as much energy systems as they were homes: warm stables, thick walls, and low, tight structures cut off air currents and saved fuel.

Material Logic: Stone, Wood, and Earth

Stone goes where stone is abundant. In limestone regions, heavy stone tile roofs are installed on thick rubble walls, and these roofs endure decades of service despite exposure to severe weather conditions. Guidelines for traditional farm buildings treat these materials as a whole (roof, walls, and mortar work together) and specify best practices to ensure their durability. The same logic applies in granite and sandstone regions: durability, weight, and a roof that is shallow enough for the stone but steep enough to drain water.

Wooden frames were prevalent in areas rich in medieval forests. The Weald region of Kent and Sussex produced large hall houses with sloping beams and projecting windows; entering a Wealden open hall today is like reading the logic of oak and carpentry in three dimensions; the large roof is supported by curved timber from floor to ridge, and the hall once vented smoke directly through the roof. Museums and case studies preserve example frames demonstrating how carpenters solved issues of joints joined with nails, wavy mud plaster, and later brick infill, addressing gaps, pressure, and weather conditions.

In areas lacking good stone or long timber, people built using the ground. Cob, an uncooked mixture of earth, straw, and water, rose in thick, monolithic layers and was protected by deep eaves and breathable lime or earth plasters. Current conservation notes emphasize that earthen walls can be beautifully preserved if their upper parts are kept dry and allowed to dry from the sides; the repair rule is gentle: match with similar materials and never fill the wall with cement.

Regional Typologies in the British Isles

The local language of England is like a mosaic reflecting its geology. In the southeast, timber-framed Wealden hall houses still show their open hall origins, while in Dartmoor, medieval longhouses stretch lengthwise on gentle slopes, with dwellings at one end and barns under thatched roofs made of threshed wheat at the other. Each type solves the same problems (heat, work, weather) with different palettes, and today their preservation often involves dendrochronology, reading smoke-stained thatch, and rebuilding traditional mortars and ridges.

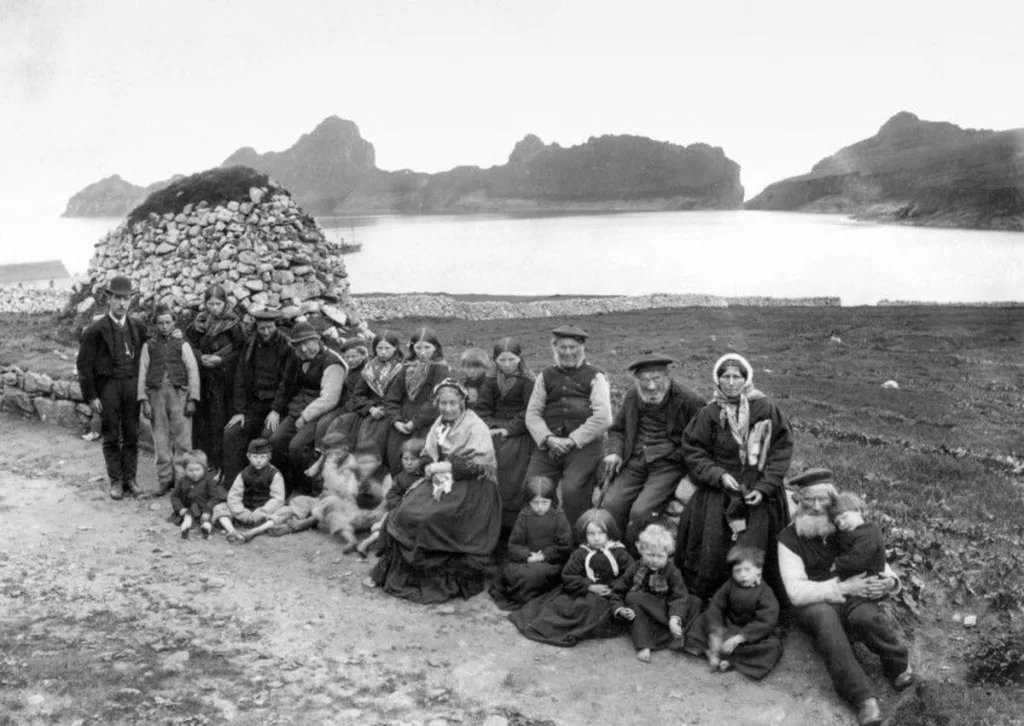

In the Hebrides islands of Scotland, black houses compress life within thick double walls, low profiles, and thatched roofs secured with nets against Atlantic storms. The design is practical and intimate: a shared roof for people and animals, widespread peat smoke that protects the thatched roof and keeps insects away, and a layout that adapts to the wind and the terrain. Contemporary heritage institutions view these houses not as outdated relics, but as high-performance solutions to exposure and limited resources.

In Wales and Ireland, long single-story, three-part thatched cottages reflect local craftsmanship using stone, earth, and straw. The Welsh term tŷ hir (meaning “long house”) typically combines the dwelling and barn in a single line; you can still study such houses in open-air collections and archival research. In Ireland, national and county programs map and protect thatched-roof houses, noting their characteristic oat straw, deep eaves, and porch-entry plans; grants and guidance are provided because these houses are both fragile and symbolic.

The Effect of Agricultural Practices on the Form

Farm work defined the boundaries of rural homes. In areas of mixed farming, the barn and dwelling being together preserved warmth, footfall, and labor at night. Calves could be heard calving within earshot, feed and family were under the same roof, and barn cleaning could be done directly into the yard. The Dartmoor longhouse is a classic English example; a cross-passage separates clean and dirty areas, with the animal section sloped for drainage. Scottish and Welsh variants also demonstrate the same economy: plans that facilitate animal care, heat sharing, and daily movement from field to hearth.

Beyond the house and barn, all the farm buildings continued to function. In the Pennines, the laithe house, the threshing barn—a linear machine for grain and cattle—and the barns were connected to the dwelling. In Historic England’s guide to traditional farm buildings, it is noted that these courtyards, rows, and roofs are inseparable from the agricultural systems that produced them, and that a good restoration respects this functional consistency as much as its picturesque appearance.

These choices resulted in sturdy and functional buildings. Stone floors were durable enough to withstand the hooves of horses shod with iron shoes; thick walls protected both animals and people; low doors and small windows blocked airflow during times when barns were full and winds were strong. Today, restoring such buildings means understanding agricultural logic (ventilation where animals are kept, sturdy eaves where carts turn) and designing new uses that ensure old circulation and moisture pathways still make sense.

The Role of Oral Knowledge and Craftsmanship Transfer

Traditional houses were built based more on memory than written sources. This knowledge was passed down through apprenticeships, family teams, and local experts (thatched roof masters, wall masons, lime plasterers). The risk is now straightforward: as older craftsmen retire, certain skills are diminishing. National skills analyses and major projects warn that large-scale restorations, such as those we would like to see for the millions of houses built before 1919, could occupy a large portion of the remaining skilled workforce.

The response, though uneven, is steadily increasing. Heritage institutions are running structured apprenticeship programs and multi-year programs to train new specialists in lime, timber, roofing, and masonry. Even cathedrals are opening training centers because there is a severe shortage of human resources in this field. In parallel, the Red List of Endangered Crafts tracks which skills are viable, endangered, or critically endangered. Recent updates highlight pressure on traditional thatch roofing in some parts of the UK and encourage targeted support.

Foundation training keeps the structure alive where it stands. Dry stone wall associations organize short-term courses and apprenticeship programs from Cumbria to Yorkshire, enabling farmers, students, and career changers to learn the rules of sound wall construction in the fields these walls protect. Similar networks exist for adobe, wattle, and lime, and institutions in Ireland and England support these through grants, advice series, and maintenance guides. These are practical ways to ensure that knowledge is passed on from hand to hand, as it always has been.

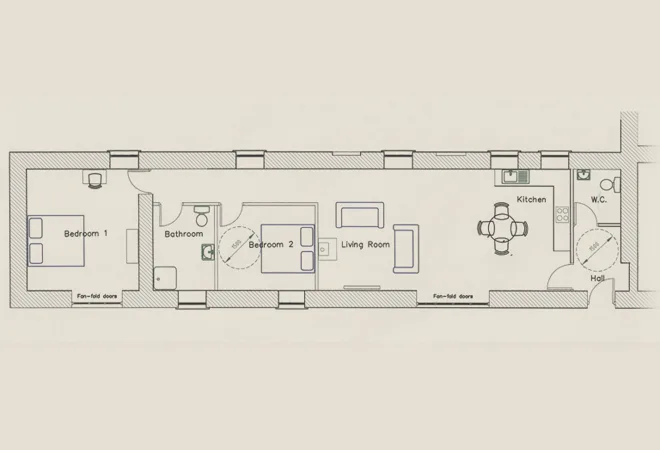

Spatial Hierarchy and Room Functions

In a rural home, the rooms are arranged to prioritize functionality, warmth, and privacy rather than abstract symmetry. One of the most enduring layouts in England is a three-part arrangement centered around a passageway: a service area at one end for storage and preparation, a hall or living area in the middle for heating and gathering, and a more private “upper” end for sleeping and status. Conservation studies and listing guidelines describe this cross-corridor plan as a defining feature of local houses, adapted over centuries without losing the fundamental hierarchy that facilitates the flow of daily life.

The longhouse in Dartmoor transforms hierarchy into a single sloping line. A cross-passage cuts through the plan; the cattle shed is on a sloping hillside, while the family rooms are on a sloping hillside to keep them dry and warm. Detailed records of surviving examples reveal how partitions and wings were later added to this core, but the original division of clean and dirty work, animal warmth, and human comfort is still clearly visible in the walls.

Elsewhere, the entrance itself indicates its function. In some parts of Ireland and England, research handbooks distinguish between direct-entry homes, where the door opens directly into the main room, and lobby-entry homes, where a small internal porch or lintel wall protects against drafts and provides storage space at the threshold. These are small changes but have big results: they control smoke, manage dirt, and determine the air quality inside the house before you take off your shoes.

Roof Forms, Chimneys, and Climate Strategies

Roofs in rural areas are primarily climate tools, with their silhouettes taking a backseat. Reed roofs, once common across much of England, provide good insulation and efficiently drain water when laid in accordance with local traditions. Current guidelines advise owners to preserve regional materials and details (ridge patterns, eave profiles, fastening elements), as these details are not decoration but methods of protection against weather conditions learned over generations. The same sources explain how supply chains and skills now influence conservation choices. Therefore, understanding the original strategy is crucial during repair or renovation.

Adding insulation to a thatched roof or altering its structure requires careful consideration, as the roof’s high thermal performance depends on its vapor permeability. Technical notes indicate that if you compromise the roof’s ability to breathe, it may lead to risks such as condensation in the air gaps, and they recommend solutions that consider both energy goals and the moisture pathways of the material. The result is a roof that retains heat where the family needs it while still functioning as intended.

Chimneys emerged to control smoke and divide the space more finely. Preservation recommendations trace the transition from open halls to smoke compartments, smoke hoods, and finally to walled chimneys in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This was a quiet revolution that allowed for the addition of floors and the specialization of room functions. Today’s maintenance guides treat chimneys as open structures requiring careful maintenance against weather conditions and heat loss, while also acknowledging their role in the ventilation of the home.

Open Hearths, Thresholds, and Symbolic Features

The fireplace is the social hub of rural homes. In medieval hall houses, it burns in the center of the room, smoke rises upward and escapes outside; later, smoke baffles and hoods concentrate the fire against the wall, creating large fireplace corners that form a sheltered area where people can sit, cook, and converse within reach of the flames. Technical notes and building histories explain how this evolution provided opportunities for cleaner air, privacy, and the creation of cozy corners that became the emotional center of the home.

Thresholds quietly do their job. A passageway or lobby filters wind and mud, provides a place to pause and rest, and protects the hearth from sudden drafts. Listing guides precisely define the passageway type, and Irish research manuals explain the hearth-lobby plan where a lintel wall forms the inner porch. This element, which may seem like a small detail, actually acts as a buffer between the landscape and living space, transforming the doorway into a small climate and ceremonial moment.

The porches and small overhangs at the entrance increase the depth of this buffer. Even modest wooden or stone porches help the house cope with the weather; they provide a place to shake off rain from your coat, store tools, or gossip without bringing the field inside. Although their forms vary greatly, the fundamental purpose remains the same: to keep the weather out, soften the entrance, and show hospitality without sacrificing warmth.

Extensions, Sheds, and the Evolution of Their Use

Rural houses grow like trees over time. In Dartmoor, you can see traces of outbuildings that were once used as kitchens or dairies, and later wings that provided additional sleeping space without disrupting the main layout. Archaeological notes on individual longhouses record these changes in wall lines and roof traces, showing a steady pattern of expansion based on need rather than a collective redesign.

With the modernization of agriculture, the number of detached sheds, barns, and dairies, each serving a different purpose, increased around homes. The guides and character descriptions used to record farms reveal common layout types (linear rows, L-shaped plans, parallel lines), clearly showing that the house and work buildings form a single organism. When read together, they reveal how families increased and diversified their capacities and then adapted their buildings when old functions disappeared.

Over the past few decades, many outbuildings have been converted for new uses. Recommendations encourage designers to enhance comfort while maintaining the agricultural character (large doors, simple volumes, authentic materials). When done well, a barn becomes a gallery, a barn becomes an office, and a carriage house becomes a kitchen, yet the story of how this place made a living is not lost.

The Relationship Between Home, Garden, and Landscape

A rural home is never isolated; it is intertwined with gardens, paths, water, and fields. Historical sources indicate that most farms adopted a courtyard layout in arable areas, with buildings surrounding courtyards where animals converted straw into manure, while livestock areas used looser arrangements to move cattle and store manure. These spatial habits reduce wasted steps, capture heat and shelter, and make the hard work a little easier on cold mornings.

On the Atlantic coast, the black house brings this relationship together under a single thatched roof; dry-stone barns are nearby, and everything is low against the wind. Arnol’s visit notes and technical case studies demonstrate how people, animals, fuel, and oaths fit into a tight choreography, proving that good positioning can be as powerful as good construction.

Even in places where farming activities have ceased, guidelines for recording farmhouses emphasize that the house, courtyard, paths, fences, and trees together form the spirit of the place. When you repair the walls, re-roof the building, or convert the barn, you also rearrange the relationship between work and land. Making these relationships understandable transforms a beautiful building from a stage set into a living landscape.

Multi-Generational Housing

Rural homes keep families together over time. On the Hebridean islands, a blackhouse can shelter grandparents, parents, children, and cattle under one roof in winter; the living room and barn are side by side. The fire in the home formed the center of family life, while the warmth and presence of the animals tied the home to the work of the land. The 42 Arnol in Lewis preserves this arrangement almost exactly, showing how closely intertwined kinship, animals, and shelter once were.

Farming is not just a series of fields, but a way of life, so households often remain tied to a single piece of land for generations. Research conducted around Arnol reveals how the memories of certain individuals and farm leases have influenced the value people place on homes today. Landscape assessments of the Outer Hebrides go even further: Farming still forms the basis of culture in this region, where thousands of active farms shape work, identity, and settlement patterns.

In England and Ireland, the theme of the “family living under one roof” experienced ups and downs alongside the economy and migration, but rural homes continued to serve as the center of shared care: young adults gradually moved out, the elderly remained nearby, and seasonal workers returned. Historical studies on household structure help explain these changes and remind us that multigenerational living is not a trend, but a deep-rooted tradition, with rural homes built specifically to accommodate it.

Rituals, Beliefs, and Home Space Habits

The rural hearth was more than just a source of heat; it was a blessing that organized the day. In Irish and Scottish homes, the fire continued to burn as a sign of continuity and good fortune, and in places like Arnol, the peat fire in the middle of the room was “the heart of family life.” The smoke perfumed the thatched roof, and when it was renewed, it even nourished the smoke-enriched hayfields. A complete cycle from the roof to the ground.

Thresholds also brought their own folklore with them. In Scotland’s Hogmanay tradition, it was believed that the first person to cross the threshold after midnight would determine the year’s fortune. Ideally, they were expected to arrive with coal or cake to ensure the house was warm and well-fed. These traditions transform the doorstep into a stage for hospitality, luck, and community gathering; a social function as clear as any architectural plan.

The room layout itself reflected silent beliefs about air, smoke, and humility. Cross passages and lobby entrances protected the fire from drafts and created a moment of “arrival” before entering the family area, while the hearth itself remained a place of blessing, storytelling, and decision-making. A study conducted in Ireland recorded the kitchen hearth as the focal point where work, food, and entertainment converged. Rituals became routine.

Gendered Spaces and Daily Rhythms

Daily life in rural homes was entirely sedentary, shaped by traditions and gender roles. In the Highlands and Islands, groups of women would gather around a table to fill newly woven fabrics by hand, keeping time with Gaelic waulking songs; work, music, and the room itself formed a single social tool. Heritage records indicate that waulking was typically performed in stages by women’s teams, with the songs changing as the fabric softened and the work being done according to the rhythm of the architecture.

Elsewhere, in the northeast of Scotland, single male farmers slept in outbuildings or back rooms and created their own song tradition. The outbuilding ballads sung in kitchens and barracks after long days in the fields recount the humor, hardships, and pride of seasonal labor. The songs survive in recordings and archives, preserving not only their melodies but also the spaces that shaped them: cold courtyards, warm kitchens, dim rooms filled with the sound of wood and stone.

Kitchen work, dairy products, and childcare typically centered women’s routines around the hearth and kitchen, while men worked in the garden, barn, and fields; however, these roles varied according to the seasons and needs. What is noteworthy is how the rooms and thresholds supported this choreography: controlling smoke, keeping tools within reach, and greeting neighbors at the door. The architecture did not so much dictate the rhythm as allow time for it.

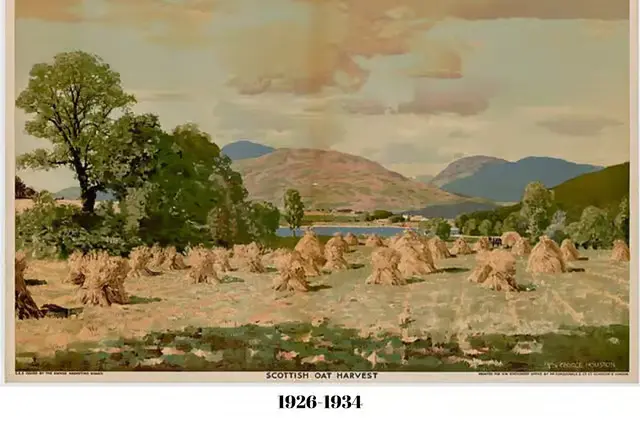

Festivals, Social Labor, and Seasonal Change

The harvest season turned the farmhouse upside down. At the end of the harvest, English communities celebrated Harvest Home “with feasts, songs, and carrying the last sheaf like the spirit of the field.” In Scotland, kirn similarly marked the end of the season. Churches later incorporated part of this calendar into the Harvest Festival, but the essence remained the same: neighbors worked together and celebrated.

In Ireland, meitheal refers to a deeper practice: when heavy work was needed “such as cutting turf, gathering hay, or harvesting potatoes” neighbors would gather at one farm, then move on to the next, labor for labor, and the work would be reinforced with food, music, and conversation. Academic and public records trace meitheal from early legal texts to twentieth-century fields, showing how the culture of reciprocity sustained small farms and made the home the center of collective effort.

The midwinter crowd brought it back to the threshold. Hogmanay’s first-foot ritual kept doors open late into the night, while the following days filled kitchens with visitors, whiskey, and songs. The role of architecture here is simple and profound: a deep porch, a warm lobby, a large table, and a steady fire make celebration possible when the wind blows and the new year arrives.

Stories, Songs, and the Memory of the Place

Rural homes preserve culture through sound. In Gaelic communities, waulking songs make up the largest portion of work songs. These songs are call-and-response pieces that incorporate the rhythm of beating cloth and the names of places, people, and weather conditions. When a group gathers around a table in a low-ceilinged room to beat tweed fabric and sing, the house transforms into an instrument that turns labor into memory.

In Scotland’s farmsteads, bothy ballads speak of plowing teams, the darkness of winter, and the camaraderie accompanied by voices after work. These songs, collected in archives and recordings, are more than entertainment; they are records of how the buildings felt to the people who lived and worked in them. They are records of how the stone floor echoes the choir and how the wooden roof warms to a slow melody.

In places like Arnol, memories are tied to rooms and the light of the fire. Research on black houses shows that visitors and descendants value these places not only for their structure, but also for the stories connected to the people remembered here, the small farms, the peat smoke, and the curves of the thatched roof. Ultimately, the rural home is a library without shelves; its pages are turned by the seasons, work songs, and the footsteps of a family moving through time.

Modernization and Rural Population Decline

Rural life in the British Isles has been reshaped by a century of mechanization, service centralization, and labor migration. The results are uneven: while some areas lose young adults to cities, they attract older migrants, creating communities that are stable in terms of population but fragile in terms of age balance. In England, government summaries show that rural areas are older than urban areas and that the proportion of the population aged 65 and over is increasing more rapidly. The mobility experienced since 2020 has generally benefited many rural area authorities, but young people aged 15-19 continue to leave the region, taking with them apprenticeship programs, school enrollments, and future caregivers for buildings requiring practical care.

Scotland exhibits the same push and pull tendencies, made even more pronounced by geography. Parliamentary and research briefings indicate that while some island groups have remained stable since 2001, others (particularly in Argyll and Bute and North Ayrshire) have declined. Highland leaders warn that without new jobs, services, and housing, double-digit declines will occur by 2040. This situation can be described not simply as “the emptying of the Highlands,” but as a mosaic of growth near centers and a quiet decline in remote areas, accompanied by a reduction in schools, buses, and clinics.

These demographic changes are directly reflected in buildings. When the number of families living near barns or black houses decreases, maintenance work shifts from an annual ritual to an occasional emergency task. Vacant property data in Scotland shows that there were over 46,000 vacant properties in 2023/24, with over 28,000 of them having been vacant for a year or longer. Each vacant property means a roof more likely to leak and a wall more likely to sag.

Loss of Local Materials and Techniques

Traditional houses, fields, and thatched roofs, pits and stones, fences and timber stores were all interconnected. These relationships have now become strained. Historic England’s 2025 guidance on thatched roofs clearly states this situation: it has become difficult to obtain reliable local straw and reeds; imported materials and non-local methods are becoming widespread; and the conservation skills once passed down from master to apprentice are declining. When homeowners change materials or techniques, this can lead to a loss of meaning as certain as the collapse of the roof facade.

Crafts lie behind the materials. The UK’s Heritage Crafts “Red List” tracks which skills are viable, endangered, or critically endangered; recent editions highlight regional thatch roofing traditions among the skills most at risk due to an aging workforce and limited training pathways. Journalism has amplified this warning: While a few crafts, such as hazel basketry and bowl-making on a lathe, have found new energy, more crafts are drifting into the danger zone. The equation for preservation is simple: Without craftspeople, there is no preservation.

Even if skills are preserved, supply chains remain unstable. Research conducted for Historic England lists the practical obstacles faced by UK straw and reed producers: agricultural science, processing, price pressure, and long delivery times that make “like-for-like” repairs difficult. Every harvest interruption becomes a minor structural risk for thousands of roofs.

Planning Policies and the Neglect of Local Values

Policy can either support or undermine local character. The National Planning Policy Framework requires decision-makers to assess damage to designated and non-designated heritage assets against the public benefit and to establish “positive strategies” for protection. In practice, the fate of an unlisted adobe barn or stone carriage house often depends on the clarity of local inventories, the time a struggling municipality can devote to the issue, and its ability to find a suitable use before decay progresses faster than permits allow.

Conversion pathways are very important. In the UK, “Class Q” permitted development allows agricultural buildings to be converted into homes without full planning permission, and recent changes made in May 2024 have expanded the scope of this. When done carefully, this preserves the use of these structures; when done carelessly, it can eliminate the agricultural character behind general carpentry and airtight cladding, preventing old buildings from breathing. Conservation advice for traditional farm buildings emphasizes the need to examine the entire complex (house, courtyard, stables) before altering any part.

Risk is tracked with numbers. Historic England’s 2024 Heritage at Risk Register lists 4,891 sites vulnerable to neglect, deterioration, or misguided development. This register serves as a warning siren and a to-do list, showing what happens when value is recognized too late and what can be saved when communities, owners, and funders are on the same page.

Decay, Abandonment, and Re-Savagery

When a rural house is enveloped in silence, nature springs into action at an astonishing pace. Vines and shrubs soften the roof lines and bind them together with lime mortar; both the risks and benefits are now accepted. Vines trap moisture and conceal imperfections, but in some cases they also protect walls from weather and pollution. Good management means managing growth, not viewing every plant as an enemy.

Some landscapes are transitioning from abandonment to intentional nature restoration. At Knepp in Sussex, the owners stopped trying to force a failing farm and allowed free-roaming herds to do the ecological work; the property then regenerated its built fabric by converting farm buildings into small businesses, creating jobs while restoring biodiversity. New projects, such as the campaign to purchase and restore a large tract of Northumberland land for nature and the local economy, demonstrate how “rewilding” can coexist with lived heritage when people, buildings, and habitats are planned together from the outset.

Elsewhere, abandonment becomes archaeology. The evacuation of St Kilda in 1930 left its houses and huts exposed to Atlantic weather. Today, the National Foundation for Climate Stress Decay separates what can be salvaged. The romance of the ruins meets the mathematics of limited budgets, and every salvaged dry stone room represents difficult choices about memory, security, and importance.

The Emotional Impact of Architectural Erasure

If a roof collapses or a garden gate opens once and never again, the loss is not merely visual. Environmental psychologists call one dimension of this feeling place attachment; it is the bonds between people and environments that shape memory and identity. When places change beyond recognition, distress follows; Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht calls this form of pain solastalgia, “homesickness at home.” In rural England, where family histories are intertwined with hearths and fences, this word expresses the feeling many people experience when farms fall into disuse.

Even as buildings decline, culture responds. Tate Britain’s “Ruin Lust” exhibition brings together the British fascination with decay that has persisted for centuries, arguing that ruins carry dual meanings of mourning and possibility: the collapse of the past into the present, and the present imagining the future from fragments. This perspective helps explain why a collapsed porch or a smoke-blackened thatched roof affects us so deeply: a rural home is a repository of labor and love, and when its structure is compromised, we grieve not only for the building but also for the form of togetherness it represented.

So the task is to turn feelings into action: to make rural life sustainable in order to keep people where they are, to secure craft channels so that repairs are possible, to use policy tools to protect ordinary local cultures and exceptional cultures, and to work with nature as much as possible rather than against it. If we do this, decline can become manageable, and destruction can lead to lived continuity rather than empty romanticism.

Passive Design and Climate Sensitivity

Regional homes read the weather and respond with their form. The same approach can guide new projects: orient rooms and openings according to the breeze, use sun-appropriate sizes and shade glazing, and allow the structure to buffer heat rather than fight it. Modern guidelines echo these common-sense steps. The UK’s Approved Specification O asks designers to limit solar gains and remove excess heat through strategies like cross ventilation and night ventilation. This is a codified version of what farmhouses and barns achieve with opposing doors, deep eaves, and small south-facing windows. CIBSE’s adaptive comfort studies support this, showing that comfort can follow the latest outdoor temperatures in free-standing buildings. Design the facade and openings well, and people will feel better with less machinery.

Putting this into practice means balancing glass, shading, mass, and air pathways. The Passivhaus Trust’s summer comfort guide requires modest, well-oriented glazing, external shading, clean ventilation, and user-friendly controls to keep interiors cool without heavy cooling systems. CIBSE TM59 adds a consistent method for testing the risk of overheating before homes are built. These two guides reward the kind of plan that builders in rural areas will embrace: windows stretching from one end of the room to the other, eaves that block high sunlight, and thick elements that absorb heat and then release it.

The renovation of old buildings should enhance comfort while preserving their vapor permeability properties. Historic England’s whole-building approach emphasizes gentle, compatible measures and long-term monitoring, so that energy efficiency improvements do not trap moisture or prevent the house from “breathing.” In short, allow the building to perform its own function, then add simple climate tactics that the building will recognize.

Material Circularity and Resource-Efficient Specification

Local construction operated in a cyclical manner: straw was turned into thatch, smoke matured the straw, and when replaced, it nourished the reed fields. Today, circular design formalizes this logic. ISO 20887 sets principles for designing buildings to be adaptable and demountable, guiding architects to use reversible fastenings, separable layers, and clear material information so components can be repaired, reused, or recycled without waste. London now requires large projects to submit Circular Economy Declarations that prioritize the reuse and preservation of existing structures. This effectively means “repair first” at the urban scale.

Since carbon is also a material issue, UK guidelines encourage a whole life cycle approach. The updated RICS Whole Life Cycle Carbon standard, which will be available for use from July 2024, provides a method for calculating emissions from production to end of life, while LETI’s Retrofit vs Rebuild “Unpicker” and UKGBC guidelines show that preserving and renovating an existing building is often more carbon-efficient than demolition. Lime-based repairs and “like-for-like” strategies for traditional facades continue to be both building-friendly and recyclable, aligning craft preservation with circular design.

Community-Based Planning Approaches

Local places are co-created by the people who live and work there. Contemporary planning has the tools necessary to bring this co-authorship back to the forefront. In the UK, the National Model Design Code requires municipalities to incorporate community views, reflecting local character and translating lived experience into clear, locally specific rules. Neighborhood planning under the Localism Act allows communities and forums to shape what gets built and how it looks, providing a guide that outlines simple steps from vision to referendum. When used together, codes and neighborhood plans can steer growth toward forms that feel local, not imposed.

Scotland’s place-based policies propose a similar idea from a 20-minute neighborhood perspective: concentrating daily needs close to homes, adapting this to rural and island contexts, and allowing community organizations to manage land that supports long-term well-being. Crofting Community Right to Buy provisions even allow communities to apply to purchase suitable small croft land for collective purposes. These tools do not replicate longhouses or black houses, but they do revive the fundamental social contract that enabled the functionality of such buildings.

Psychological Comfort and Spatial Familiarity

People feel comfortable in rooms that behave as our minds expect: easy to understand, easy to control, and quietly rich. Recent research in environmental psychology reveals that our responses to environments are shaped around dimensions such as enchantment, consistency, and home-like warmth. These characteristics are found in traditional homes with textured materials, legible plans, and a hearth-centered focus. Attention Renewal Theory adds that contact with nature renews mental focus. This explains why work gardens, fences, and sky views feel like part of the room rather than just scenery.

Material selection is also important. Studies on wooden interiors have shown that they have stress-reducing effects compared to non-wooden rooms, highlighting the physiological benefits of warm and tactile surfaces. Simple touches such as wood paneling you can touch, lime plaster that softens light, and deep moldings that frame the view transform new health standards without imitating old atmospheres. In other words, designing for comfort is as much about emotions and control as it is about kilowatt-hours.

Time-Tested Flexibility and Seasonal Modulation

Traditional homes have a flexible structure according to the calendar. In winter, life centers around the warm core; in summer, doors open to the breeze and activities move to the veranda, garden, and sunbathing areas. Contemporary low-energy projects demonstrate how this choreography can be deliberately designed. The Hockerton Housing Project utilizes a south-facing sunbathing area and high thermal mass, enabling the house to absorb winter sunlight and retain heat during cool nights, thereby reducing the need for active heating. The same envelope remains comfortable in summer through ventilation and shading.

Standards now require designers to demonstrate this seasonal balance. The Passivhaus guide clearly sets comfort targets for summer months and encourages external shading, modest glazing, and night cooling, while England’s Part O section offers simple methods to limit solar gain and remove heat, highlighting cross ventilation as a particularly effective method. All of Historic England’s building recommendations complete the cycle by encouraging post-occupancy adjustments and maintenance, acknowledging that the building’s flexibility can be maintained if owners and users make continuous adjustments. This is an updated version of the old rhythm: design for the seasons, then live with the building as it changes.

The Future of Rural Homes in British Architecture

Adaptive Reuse and Rural Revitalization

Rural resilience often begins with a careful second life. Converting working buildings (barns, haylofts, car garages) does not disrupt the settlement pattern, reduces carbon emissions, and creates space for new livelihoods. Historic England’s guidance on adapting traditional farm buildings explains the simple rule that makes this work: first understand its significance, then ensure new uses fit the old structure, from openings to roof pitch and courtyard relationships. This approach transforms buildings into living spaces rather than stage sets.

Recent landscape-scale projects demonstrate how heritage and local economies can develop together. At Knepp in West Sussex, rewilding went hand in hand with the reuse of farm buildings for small businesses and visitor infrastructure; the estate reports hundreds of local jobs and strong nature tourism revenue, alongside major biodiversity gains. In other words, the farm has become a rural business hub again, with different tenants and species.

In the north, wildlife foundations and their partners are acquiring large tracts of land for nature restoration tied to viable villages and resilient buildings. The Rothbury project in Northumberland exemplifies the new model: raising capital for land restoration, balancing restoration with grazing, developing ecotourism, and incorporating community support. This economic plan works as long as homes, farms, and local services remain in use.

Revitalization of Local Architecture Led by Architects

New generation applications are renewing the rural structure without imitating the past. In the Skye and Highlands region, architecture firms such as Rural Design and Dualchas have approached small farmhouses and cottages as living typologies, redesigning them with today’s materials, budgets, and weather conditions in mind, featuring simple sloped volumes, sturdy exteriors, and sheltered entrances. Their work demonstrates how modest scale, careful placement, and thoughtful details can evoke both a contemporary and site-specific feel.

Elsewhere, detached houses serve as manifestos. David Kohn Architects’ Red House in Dorset (winner of the RIBA 2022 House of the Year Award) uses brick, eaves, and dormers to create a characterful, climate-friendly, and forward-thinking country home.

WT Architecture’s Taigh na Coille house in Sutherland, sheltered from wind and rock by high insulation, low-carbon materials, and sweeping views, reminds us that performance and belonging can coexist under one roof.

Low-tech innovations also have their place. Invisible Studio’s “Ghost Barn” project demonstrates that local logic—using locally sourced timber and fast, economical assembly methods—can be applied without compromising on quality, from workshops to homes, utilizing local resources, minimal processing, and reparable structures.

Policy Changes and Estate Management

The rules are changing and are significant in rural areas. The UK’s National Planning Policy Framework was revised in December 2024 and updated again in February 2025; it continues to place great importance on heritage, but is pushing for more housing, infrastructure, and climate action, thereby altering the context of rural design and conservation. Commentators note that the concept of the “gray belt” has been introduced to facilitate the development of degraded green belts. This change will test how well design rules and heritage policies can preserve character as implementation accelerates.

At the micro level, the development rights permitted under Class Q were expanded in May 2024, making more agricultural buildings suitable for conversion into residential properties. This is an important tool for preserving farm buildings, provided that designers take into account the building’s breathability, structure, and location, as heritage consultants have repeatedly emphasized.

The administration continues to race against time. Historic England’s 2024 Heritage at Risk Register lists 4,891 entries of buildings and sites vulnerable to decay, neglect, or changes made through poor decisions. This register also serves as a planning map: it shows where public funds, community efforts, and good design can transform decay into resilient use.

Training Designers with Local Wisdom

Tomorrow’s rural homes will be as good as the questions their designers ask. The Architects Registration Board’s new competency framework places climate, safety, and ethics at the heart of architectural education and reshapes how education providers structure learning. Meanwhile, RIBA is implementing mandatory competency tests and climate literacy programs to ensure graduates can translate local knowledge into strong performance.

Site skills are also transferred through planning tools. The National Model Design Code and pilot applications encourage municipalities and communities (including rural ones) to write locally specific rules for form, material, and layout, thereby transforming tacit knowledge into explicit and testable design parameters. When used correctly, codes help small villages steer growth toward forms they can claim as their own.

Digital Tools for Local Documentation

Records are rapidly being transferred to digital formats. In Scotland, Historic Environment Scotland decommissioned its old platforms in June 2025 and launched Trove.scot as the gateway to the National Historic Environment Records. This platform is a combined, searchable map of places, descriptions, and archives that facilitates the discovery and use of evidence in rural areas. In England and Wales, Heritage Gateway and Coflein offer parallel portals to sites, images, and records supported by local Historic Environment Records.

Open spatial data now brings land and definitions to every table at survey level. The Environment Agency’s national LiDAR program provides 1-meter elevation data across the UK, and this data is invaluable for reading settlements, roads, and water sources. DEFRA’s MAGIC viewer helps teams reduce site risks before visiting by presenting various definitions, from SSIs to agricultural environment programs, in layers. Combined with Historic England’s record guides and APIs, along with growing photogrammetric 3D model libraries, this provides small rural projects with the kind of evidence once reserved for large-scale plans.

What brings all of this together is attitude. Consider the rural home as a working tool adapted to weather conditions, terrain, and community, and every tool, from the design code to the LiDAR car, becomes a way to keep this tool operational. A future where reuse funds are prioritized, policies reward ownership, and education teaches designers to listen first and then draw seems most promising.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.