Courtyard architecture is a universal language spoken in different dialects across civilizations. Two prominent typologies are the Ottoman courtyard, which is the sincere courtyard of the Turkish-Islamic tradition, and the Roman atrium/peristyle, which extends to medieval passageways and Renaissance courtyards. a5> to medieval passageways and Renaissance courtyards extending from the Roman Latin courtyard. At first glance, both are simple open-air spaces, but they crystallize fundamentally different worldviews. The courtyard is an inward-looking oasis that embodies Islamic values of privacy and spirituality, often simple on the outside but a paradise within. In contrast, the Latin courtyard tends to exalt an outward-looking order and human-centered harmony, from the public splendor of the Roman atrium to the symmetrical monastery gardens symbolizing Paradise. This article examines five dimensions of these courtyards—climate and materiality, ritual use, threshold design, geometric ideals, and modern reinterpretations—to understand how environment and culture shape different identities. It will take us on a journey from the sun-baked landscapes of Anatolia to the sunny markets of the Mediterranean, from the murmuring of ablution fountains to the silence of monasteries, and ultimately reveal how contemporary architects have reimagined these traditions. The aim is a rich, narrative exploration supported by scientific understanding and vibrant spatial storytelling.

Climate and Materiality: Open-Air Living Versus Indoor Oasis

Climate is perhaps the most decisive factor in the shape of courtyards. The Ottoman courtyard developed in hot, arid, and Mediterranean climates, requiring inward-looking designs that provided shade, coolness, and protection from the harsh sun. In contrast, the classical or Latin courtyard developed in the mild Mediterranean and European climates, which allow for more open and airy configurations. These environmental differences have led to contrasting strategies in terms of materials and form.

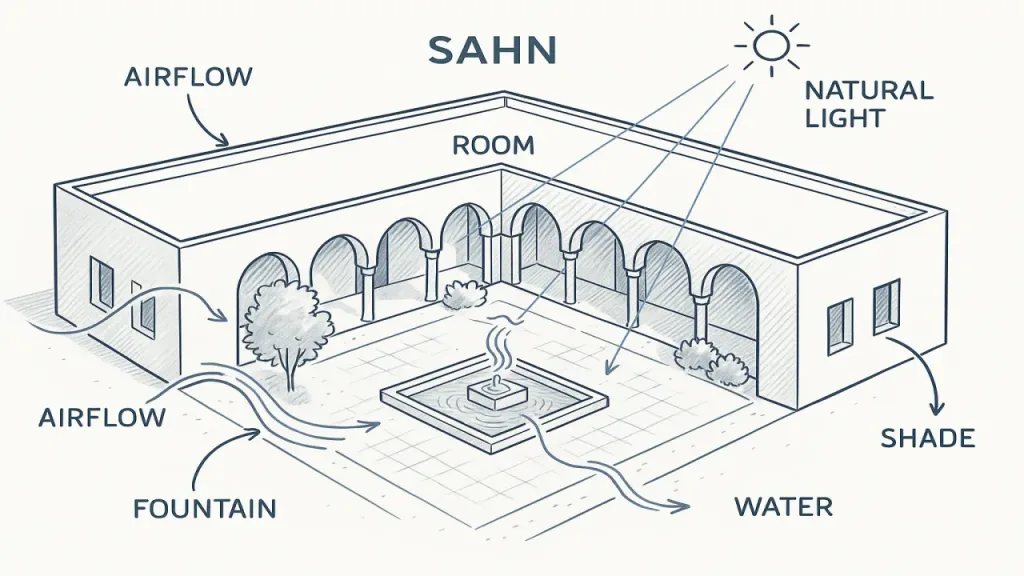

Figure 1: Diagram of a traditional Islamic courtyard (sahn) showing passive cooling (shaded arcades, a central fountain for evaporative cooling, and inward-facing windows) that creates a cool microclimate.

In Ottoman and broader Islamic architecture, courtyards serve as oases. The walls are high and empty on the outside, the plan is inward-facing, and the ratio of the enclosed space to the openness to the outside is maximized. Courtyards feature elements such as water pools, fountains, and lush vegetation, which are not merely decorative but also provide critical climate control. The presence of water at the center (such as the fountain in the mosque courtyard) evaporates to provide cooling and a calming environment, making the air literally more bearable during extreme heat. Deciduous trees and vines have been planted to provide seasonal shade. These features create a sharp thermal contrast: as one writer observed, “there is a deliberate contrast between the sharp, bright heat of the outside and the intimate, shady coolness of the inside.” As a result, a comfortable microclimate—a courtyard that acts as a heat absorber—emerges, enabling life to thrive even during the scorching summer months. Traditional materials take this goal even further: thick stone or adobe walls provide thermal mass, absorbing heat during the day and releasing it at night, while the light-colored marble flooring in the courtyard stays cool when wet. Ottoman courtyards were typically paved with stone and marble (which keep cool) and surrounded by arcades that diffuse sunlight. At its core, the courtyard transforms extreme climate into a richness by harmoniously integrating natural elements—earth, water, and wind—into architectural design.

In contrast, the Latin courtyard (exemplified by Roman houses and later European palazzos or monasteries) developed under more mild, temperate conditions that allowed for more outward-looking designs. In many Roman and Renaissance examples, the courtyard is a place that invites light and air in rather than keeping them out. Therefore, courtyards in cooler or less arid climates tend to be more open to the surroundings, with larger window openings, lower walls, and even facades facing outward. For example, in temperate regions, “the size of windows facing the courtyard is large to obtain more sunlight”—a priority unimaginable in the sun-baked Middle East. Roman peristyle courtyards were often surrounded by colonnaded arcades, but were open to the sky and breezes, sometimes containing ornamental gardens rather than deep shade. The Romans included fountains and shallow pools (impluvium) in their atriums, but these were not used as an absolute necessity for cooling, but primarily to collect and decorate rainwater. The materials used in the Latin context—brick, stone, and fired clay—offered thermal stability in a different sense: thick walls kept buildings warm on cool nights and provided structural integrity, but the need for protection from excessive sunlight was less pronounced. In Spanish and Italian Renaissance courtyards, greenery and open arcades create an airy, pleasant open-air room for enjoying the mild climate rather than a tightly enclosed shelter. A study on courtyard types notes that tropical and temperate courtyards have a more “porous texture,” blurring the boundaries between interior and exterior spaces, while hot and dry courtyards are “more closed and sheltered.” The Latin courtyard is an example of the former: it usually embraces the surrounding environment—a portico opening onto a garden or a walkway with one side open to the view. If the courtyard is an inward-looking paradise, the Latin courtyard is an open square—a place where one can breathe fresh air under the sun or stars.

Figure 2: Plan of a typical Roman domus (city house) with an atrium and peristyle courtyards. Roman courtyards were open to light and usually surrounded on all sides by living quarters, reflecting a more outward-looking use of climate (allowing for sunlight and ventilation) suited to the milder conditions of the Mediterranean.

In summary, while the climate turned the Ottoman courtyard into a shaded sanctuary—with thick walls, an inward focus, and water and greenery that actively cooled the air—the Latin courtyard became an open-air salon that balanced sun and shade for a temperate lifestyle. Each was a direct response to the environmental context: the former an architectural response to heat and aridity, the latter an adaptation to mild, breezy climates. These choices also influenced the choice of materials: the cool stone courtyards and the sound of fountains in Istanbul contrasted with the sun-kissed brick arches and lemon trees of an Italian garden. Climate was the silent sculptor of these spaces, providing comfort while also giving each courtyard type its own unique atmosphere.

Ritual and Cultural Use: Ablution and Exposure versus Privacy and Sociality

Beyond the climate, it is the ritual and social life within these courtyards that give them their true spirit. Ottoman and Latin courtyards have been the scene of very different daily activities, depending on the cultural and religious norms of their societies. By examining how people used these spaces—for prayer or power games, quiet family gatherings, or public ceremonies—we uncover the deeper meanings embedded in their design.

In the Islamic-Ottoman context, the courtyard was filled with sacred and special functions. Whether it was a mosque, a madrasa, or a traditional house, the courtyard was not just an empty space, but a tool for spiritual and social practices. For example, almost every large Ottoman mosque has a central courtyard (sahn) with a ritual ablution fountain (abdestçe) where worshippers perform ritual purification (abdest) before prayer. This transforms the courtyard into a sacred space before prayer, a place where physical and spiritual cleansing takes place under the open sky. The gentle trickling of the fountain and the cool marble floor create a contemplative atmosphere for prayer. In the courtyard of the house, the family would gather in the mornings and evenings, with women and men resting in the shade and children playing within the safety of the walls. More importantly, the courtyard allowed for hospitality in privacy—a fundamental Islamic virtue. Guests (especially male guests) could be received in the courtyard or in an adjoining room without ever looking into the family’s private quarters. Traditional houses in Damascus, Cairo, or Istanbul usually had a two-part layout: an outer courtyard (barrani) for guests and an inner courtyard (jawwani) for the family, providing a balance between hospitality and seclusion. The entrance to these houses was also designed to preserve this sanctity—a sloping corridor that prevented outsiders from seeing directly inside (we will examine this threshold in a moment). All of this stems from cultural priorities: humility, family privacy, and spiritual focus. The philosophy can be summarized as “privacy and seclusion, with social status displayed to the outside world at a minimum”—the courtyard was the hidden heart of the house, where life could unfold away from prying eyes. Activities here included the daily rituals of Islamic life: the family breaking their fast in the courtyard during Ramadan, women doing housework together, elders telling stories to children under the trees. Even sound was part of the ritual environment—the courtyard was often filled with the soothing trickle of water and the chirping of pigeons, fostering a sense of peace. At its core, the courtyard was a microcosm of Islamic morality: hospitable yet modest, open to the sky (and thus symbolically to God) but closed to the street, facilitating worship and family ties.

Figure 3: An Ottoman mosque courtyard (Beyazıt Mosque in Istanbul) with a domed portico and central fountain (şadırvan) for ablutions. Such courtyards serve as both a spiritual preparation area and a social center for worshippers, demonstrating the role of the courtyard in Islamic ritual.

In contrast, the Latin courtyard (especially in classical and Renaissance usage) had a more public and status-oriented role reflecting Greco-Roman and later Christian-monastic cultural values. In ancient Rome, the courtyard of a house was the center of civic life for the elite. A Roman paterfamilias would receive his clients in the courtyard every morning (salutatio ritual) to demonstrate his power and benevolence. The design of the atrium reflected this function: it was usually the most lavishly decorated part of the house, with marble busts of ancestors, expensive mosaics, and an open roof to impress visitors with a view of the sky. A historical account notes that because customers and guests waited here, the owner “ensured that [the courtyard] was well decorated with attention and money.” It was a place of display and prestige, almost a semi-public courtyard within a private domus. Beyond the atrium, in many Roman houses, a second, more private courtyard—the peristyle garden—served as the family’s dining and entertainment area. These peristyles emphasized planted nature: colonnaded walkways, statues, fountains, flower beds. In the cool hours of the evening, they served as places of leisure and reflection where philosophical conversations or fading banquets could take place in the fragrant air of a walled garden. The contrast with an Ottoman courtyard is striking: Roman courtyards were not so much places of seclusion as they were places of being seen and seeing either by socially dependent individuals or by one’s own household and guests.

Throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, courtyards continued to exist in the form of monastery cloisters, each with its own rituals, and palace courtyards. The square courtyard of the monastery, surrounded by covered ambulatory corridors, became a symbolic sacred space. Monks and nuns used the corridors as a place to walk while praying, read sacred books, or contemplate nature in silence. Many monasteries were designed with a central fountain or well, and their gardens were often divided into four sections, clearly evoking the Christian symbolism of the Garden of Eden. The enclosed garden with a water source at its center symbolized paradise and recalled the four rivers of Eden. Still, monasteries had their daily uses: the central courtyard served as a gathering point connecting the monastery buildings, sometimes used for mundane tasks like washing clothes or drying herbs, always within the monastery’s quiet order. The soundscape here was the exact opposite of the courtyard fountain—perhaps the chirping of birds or just the echoing footsteps under the arcades in an atmosphere of disciplined silence. Meanwhile, in Renaissance palaces and Spanish houses, the courtyard (veranda) became a place for social life and displays of power. For example, in Spain, the courtyard of noble houses was a place for celebrations and family ceremonies and a status symbol—it was often decorated with arches and balconies where musicians could play and guests could be entertained. Thus, we see that the meaning of the Latin courtyard has evolved from the sacred to the ceremonial: it can be a closed Paradise for religious devotion or a stage for worldly affairs and pleasures.

In summary, cultural practices have assigned different roles to the courtyard and the Latin courtyard. The courtyard was essentially introverted and multipurpose: a place for ablutions, teaching the Quran to children in the shade, women gathering away from prying eyes, and showing hospitality without compromising privacy. The Latin courtyard was more outward-looking or social: a place for displaying virtue or wealth (ancient Rome), contemplating the divine order (monastery cloisters), or socializing (Renaissance palace). These uses influenced the design: the high walls, fountains, and prayer rugs of the courtyard facilitated an intimate, devout atmosphere, while the symmetry, arcades, and formal gardens of the Latin courtyard facilitated visibility, interaction, and often a show element. Each courtyard type became a theater for the daily rituals of its culture—one the “open-air room” of piety and private life, the other the “closed square” of social life and representative display.

The Concept of Threshold: Layered Privacy and Axial Openness

One of the most illuminating differences between Ottoman and Latin courtyard traditions lies in how one enters the courtyard, that is, in the threshold condition. The threshold is the transition from the public space to the protected courtyard, and its design reveals how each culture negotiates privacy, sacredness, and accessibility.

In Ottoman architecture, thresholds are usually carefully designed, layered transitions that protect privacy and sanctity. The journey from the street to the courtyard is rarely direct. For example, many traditional Islamic homes feature a “curved” entrance corridor (dihliz): before opening onto the courtyard, one enters a narrow hall that turns around a corner. This clever arrangement means that even if the door is momentarily open, an outsider cannot see directly into the family’s living space—the curves block the view and also muffle noise and dust from outside. This is a physical manifestation of the value placed on privacy and modesty. As described in a narrative set in Damascus, “the winding corridor layout ensured privacy by preventing passers-by on the street from seeing inside the residence.” Only after passing through this winding entrance does the visitor step into the bright courtyard and often experience a dramatic sense of revelation. — the famous “wow effect” of passing from a simple street to a lush courtyard (truly, as a 19th-century traveler marveled, “a golden core within a clay shell”). This layered threshold continues inside the house: semi-open porticos or eyvan surround the courtyard and serve as intermediate rooms between completely enclosed rooms and the sky-lit courtyard. An eyvan (a vaulted semi-enclosed porch) or Turkish sofa (veranda) is intentionally a liminal space—neither completely inside nor outside. It is a place where a guest can be welcomed with drinks or where family members can relax in the breeze and enjoy the courtyard in the shade. Culturally, these intermediate spaces convey a sense of hospitality and a polite protocol; they filter who can enter. Even in large complexes such as Topkapı Palace, the idea of sequential thresholds is very important. Topkapı is organized as a linear progression of courtyards, each entered through a monumental gate and each more private than the last. The first courtyard was open to the public, the second was for official business, the third was for the royal family, and so on. Moving inward was like passing through concentric layers of privacy and privilege marked ceremonially by thresholds (doors, halls, screens) that signified increasing sanctity or secrecy. As researchers have noted, “[Topkapı’s] courtyards are clearly defined as public, semi-public, and private spaces according to hierarchical concepts.” Threshold spaces—usually shaded porches or domed entrance halls—prepared people for the next realm. Mosques also typically feature an intermediate passageway or arcade along the edge of the courtyard where worshippers remove their shoes and mentally transition from the secular to the sacred realm. Thus, in Ottoman design, the threshold is ritualized and spatially reinforced. It serves as a buffer (protecting the interior from direct exposure), a filter (controlling who and what enters), and a symbolic boundary of the sacred. The shaded porch or eyvan is often filled with reverence—one steps into it by passing over a small elevation, such as a sacred rug, before entering a room. In summary, the Ottoman courtyard is jealously protected by threshold layers and reflects a worldview that values intimacy, gradual revelation, and controlled access.

In contrast, in the Latin (classical and Renaissance) tradition, courtyard thresholds are generally more open and axial, emphasizing continuity rather than seclusion. The Roman domus is a clear example of this: typically, one entered the house from the street through a short entrance (fauces) that opened onto the atrium in a straight line. In most cases, one could stand at the entrance and see all the way to the columns of the peristyle garden beyond the atrium—a powerful axial vista deliberately designed by the architects. This was about visibility and transparency: a guest passing through the threshold was immediately placed at the center of the house’s public space, with the line of sight usually ending with a view of the richly decorated tablinum (office) or the greenery beyond. There was little thought of hiding the interior; on the contrary, the architecture invited the eye inside. Roman houses faced the street with a relatively empty façade (for reasons of security and noise), but once you passed through the street door, you were in a series of open, harmonious spaces aligned on an axis. In this context, the threshold—perhaps marked by a small porter’s room or a pair of columns—was not intended to hide the interior but to ceremonially frame it. In monasteries and cloisters, thresholds are similarly open: typically a simple door or passageway leading from a church or outer courtyard into the cloister, usually without elaborate curves or concealing elements. The monastery was intended to be an open courtyard accessible to all members of the monastery, so the threshold from the surrounding corridors was more a matter of passing through a passageway than negotiating a secluded entrance. Renaissance palaces in Italy typically had a large door opening onto an arched courtyard from the street; here, the threshold (an ornate arch or portal) emphasized formality and symmetry rather than privacy. Visitors stepped into a courtyard that was visible from the moment they entered—a showpiece of architecture that again emphasized the Renaissance ideals of transparency and proportion. Indeed, Renaissance design guidelines emphasized aligning the entrance axis with the center of the courtyard or garden to create a view that revealed order and invited exploration. We can say that the Latin approach to thresholds reflected a cultural comfort with permeability and display: in a social environment where status was displayed and architecture was a means of expressing humanist ideals, one did not hide beauty behind too many veils. Instead, the threshold often provided a dramatic display, similar to a proscenium where the inner courtyard could be seen immediately.

It is important to note that they recognized the spatial hierarchy of Latin traditions (from public to private), but achieved this through plan organization and decorum rather than physical partitioning. For example, in a Roman house, private bedrooms may be located away from the courtyard, and in a monastery, only certain individuals may enter the monastery, but once entry is permitted, the spatial design itself is simple. In the Ottoman tradition, there could be additional thresholds even within the courtyard—for example, a raised semi-open room (eyvan) for honored guests and more secluded rooms for the family. Thus, one system supports a continuous spatial flow and visual openness, while the other emphasizes partitioning and indirect progression.

A Latin courtyard is usually connected to the outside—for example, Italian villas of the Renaissance placed their courtyards extending toward gardens or landscapes to strengthen an open relationship with nature and the city. Meanwhile, courtyards in Ottoman houses are inward-facing and typically do not align with street grids or create outward-facing vistas—in fact, they often turn away from the outside world or are oriented independently of street alignment toward the qibla, thereby disrupting external symmetry in favor of an internal logic.

In summary, the threshold in Ottoman courtyards is related to creating a sacred or special intermediary—a sense of transition between shadow, shade, and the protected area. As one moves from the bright, chaotic street to the cool, semi-lit entrance and then into the tranquil courtyard, there is a psychological transition by design. In the Latin courtyard, the threshold is more like an open door or a framing arch—usually a single monumental arch or entrance door that quickly leads to the central space, signaling openness and human control of the space. Both approaches convey a great deal: Ottoman architecture treats the house or mosque as a sacred area that must be entered slowly, in harmony with norms of spiritual introspection and privacy, Latin architecture generally treats the courtyard as an extension of the civil space or nature, where one can step in with relatively little ceremony, in harmony with a worldview that trusts in the presence and visibility of humans in space.

Geometry and Worldview: Divine Orientation and Human-Centered Order

Architectural geometry—the shapes, proportions, and symmetry of space—encodes a culture’s philosophical worldview. Ottoman-Islamic and Latin-Christian (or classical) courtyard designs are no exception. By examining their typical proportions and layout geometry, we uncover an implicit dialogue: one between a orientation toward the divine and the acceptance of asymmetry, and the other between human-centered rationality and classical symmetry.

The Ottoman courtyard typically exhibits an adaptable, organic geometry guided by functional needs (such as orientation toward Mecca or spatial context) and a theological aversion to ostentation. Traditional Islamic architecture has not always insisted on perfect symmetry in plan; instead, it has valued orientation and hierarchy. For example, in a mosque courtyard (sahn), the qibla axis (the direction towards Mecca) is very important—the courtyard may be rectangular with the prayer hall on the qibla side, and even if this breaks strict symmetry, it gives more emphasis to this side (usually with a deeper portico or a larger iwan). This reflects a worldview in which the design accepts a direction (towards God) beyond itself. There may be a fountain in the center of the courtyard, but unlike a Renaissance courtyard focused on a human statue or secular focal point, the Islamic fountain is for ablutions—not a human figure, but a ritual center. The spatial composition thus shifts the emphasis from the human to the divine focus (direction of prayer, ritual purity). Furthermore, courtyards in houses have been shaped by the pragmatics of privacy and land constraints, resulting in irregular or L-shaped courtyards when necessary. Islamic cities such as Fez or Aleppo grew organically; a courtyard could be outside the center or not be a perfect square, adapting to the dense surroundings. This was acceptable as long as it served the purpose of the space—cooling, gathering, privacy. There was no equivalent to Vitruvius’ dictates that a courtyard in the Islamic tradition must conform to ideal proportions; instead, builders often used proportional systems (geometric tile patterns, etc.) in decoration, while the layout could be more free-form. However, symmetry is more common in official settings such as imperial caravanserais or madrasas—but even there, one side is usually different (e.g., the side with the prayer iwan is larger). We can say that the Islamic approach to courtyard geometry emphasizes a hierarchy (some sides are more important) and a cosmic orientation (qibla) rather than pure bilateral symmetry for its own sake.

The Latin courtyard, especially during the Renaissance, summarized the ideal of classical symmetry, proportion, and geometric perfection. This goes back to Greco-Roman principles (Vitruvius’ writings on harmony and module) and was enthusiastically revived in the 15th century. A Renaissance courtyard, for example in an Italian palace, is typically a regular rectangle or square with symmetrical arcades on either side, each section repeating in a harmonious rhythm. Proportions may follow simple ratios (1:1 or 2:3 for a square, etc.) that reflect the belief that mathematical order is the foundation of beauty and truth. This approach places the human mind and aesthetics at the center: the courtyard is often aligned with the grid of a building and the grid of the city, organizing it into a regular void within a regular whole. The worldview here is humanistic—summarized by something as famous as Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man drawing, which places the human figure as the measure of all things within a circle and a square. Similarly, the classical courtyard also places human activities within a regular geometric form, suggesting that order (symmetry, axis) is aligned with the order of the world. For example, a monastery is typically a perfect square—its four sides not only evoke theological symbolism but also embody the classical love of the square as an expression of balance. Renaissance architects such as Alberti and Palladio made great efforts to achieve geometric purity; Palladio’s villas are typically symmetrically placed and proportioned to reflect their façade arrangements, striving for ideal consistency with central courtyards or atriums. This reflects the Renaissance worldview of the cosmos reflected in human designs—the belief that designing a courtyard with precise symmetry and centrality reflects the rational cosmos created by God and that humans are the interpreters of this cosmic geometry.

From a practical point of view, Latin courtyards have generally facilitated axial views and the centrality of the observer. When you stand in a Renaissance courtyard, you can typically stand in the middle and feel equidistant from all sides, framed by the architecture—a subtle elevation of the courtyard user. In contrast, stand in the courtyard of an Ottoman caravanserai: you may find your attention drawn to one end by an important iwan or fountain that breaks the symmetry but emphasizes function (perhaps opening onto a prayer hall). While the center of Islamic courtyards can be left symbolically empty or filled with water and plants (evoking paradise), a Baroque European courtyard may feature a statue of the patron or a monumental fountain celebrating worldly splendor at its center. These choices reveal whether culture places God or man at its conceptual center. Islamic thought generally avoids representative symbols at the center (there are no statues, because figurative representation has been discouraged) and instead uses water or geometric patterns—perhaps to imply that God’s presence (even if invisible) is central, or that the beauty of nature (as a sign of God) is central. Western classical thought reinforces anthropocentrism by comfortably placing a human figure or a proudly proclaimed symbol at the center of a courtyard (think of a king’s statue in a palace courtyard).

Osmanlı ve daha geniş anlamda İslami tasarımda geometrik titizlik vardı ancak bu titizlik genel simetrik hatlardan ziyade plan alt bölümlerinde ve süslemelerde ortaya çıkma eğilimindeydi. Avrupalı ziyaretçilerin de belirttiği gibi Topkapı Sarayı, Avrupa saraylarına kıyasla “düzensiz, asimetrik, eksenel olmayan ” bir görünüme sahipti. Yine de bahçelerinde ve köşklerinde karmaşık modüler planlar ve küçük ölçeklerde (çini işçiliğinde, kubbe oranlarında vb.) altın oran uyumları vardı. Sanki İslami yaklaşım belli bir karmaşıklığı ve katmanlaşmayı benimsemiş gibidir – bütünün basit bir Platonik form olması gerekmez, ancak bütünün içinde düzenli bir desen cenneti yatar. Latin yaklaşımı, özellikle de resmi mimaride, tüm topluluğun kendisini net bir geometrik form, bir bakışta görülebilen insan tarafından empoze edilmiş bir düzen ifadesi haline getirmekti (örneğin, Michelangelo’nun Roma’daki mükemmel yamuk Campidoglio avlusu veya Santa Maria della Pace’nin kare manastırı).

In summary, proportions and geometry in these courtyards reflect broader worldviews. Even if the geometry of the courtyard introduces asymmetry or hidden order, it generally suggests a world where God’s guidance (Mecca) and practical humility guide the design. This is a worldview that is comfortable with mystery and inner focus—the beauty of a courtyard may not reveal itself in a balanced exterior façade, but rather in the layered symmetry of its arches or in the four-part chahar-bagh garden metaphor (paradise garden), which is a cosmic geometry of its own kind. The Latin courtyard proclaims a worldview of clarity, human scale, and outward harmony—it strives to impress with obvious symmetry and proportional perfection that echoes classical ideals where “symmetry, proportion, geometry” are key. Poetically speaking, one could say that while the Ottoman courtyard points upward (to the sky through its open roof) and beyond itself, the Renaissance courtyard points to an ideal geometric center where man can stand and feel in control. Each is beautiful within its own philosophy—one is the earthly echo of the divine paradise, the other a microcosm of the rational cosmic order.

Modern Mergers and Adaptations: From Revival to Hybrid Innovation

Despite their different origins, courtyards and Latin courtyards have generally undergone a Renaissance in contemporary architecture, often combining their principles in hybrid forms. As designers today seek sustainable and human-centered environments, courtyards are making a comeback, drawing inspiration from both Ottoman and classical examples. Let us examine a few examples and trends that illustrate how these typologies have evolved or converged in the modern era.

Revivals Inspired by the Ottoman Empire: Many modern architects in Turkey and the Middle East have consciously drawn on the legacy of the courtyard. Turgut Cansever’s Demir Tatil Köyü (Bodrum, 1980s) is an award-winning project that reinterprets the local Mediterranean-Turkish courtyard house for a holiday village community. Often referred to as a “wise architect” in Turkey, Cansever believed in using traditional forms to achieve environmental harmony. In Demir Tatil Köyü, clusters of holiday homes are arranged with courtyards and terraces that evoke the feel of an Ottoman coastal village. The design uses thick stone walls, wooden screens, and whitewashed surfaces to keep interiors cool (a nod to climatic function) and arranges houses around semi-private courtyards that encourage community interaction while respecting privacy. Cansever’s team has clearly rooted their architectural language in “Greek, Byzantine, and Ottoman precedents” and integrated them into a modern form. The result is a contemporary environment that feels timeless, with bougainvillea-covered courtyards and pergolas open to sea breezes yet as intimate as an old Anatolian house. This demonstrates how the “DNA of the courtyard”—climatic sensitivity and enclosed social spaces—can be transferred to new contexts. Another acclaimed project is Emre Arolat’s Sancaklar Mosque (Istanbul, 2013). This contemporary mosque breaks away from Ottoman historical style, yet interestingly reinvigorates the spirit of the stage in an abstract way. The mosque is situated on the slope of a hill with a garden and a reflecting pool at its entrance, surrounded by high stone walls that separate it from the noisy outside world. Passing through nature, between water and wildflowers, one enters a tranquil courtyard-like forecourt before reaching the prayer hall. This design strategy—using a sunken, sheltered courtyard as an entrance hall to prayer—clearly reflects the traditional mosque courtyard that prepares worshippers for prayer. The architects of Sancaklar note that “the high walls surrounding the upper courtyard draw a clear boundary between the chaotic outside world and the tranquil atmosphere inside.” One side of the courtyard is defined by a low tea house and library pavilion set within a shallow water pool, which reinforces the reflective, oasis-like atmosphere. Although formally ultra-modern (raw concrete and rock, no overt historical ornamentation), Sancaklar Mosque demonstrates a modern rediscovery of the courtyard concept – using landscape and enclosure to create a spiritual refuge and using the threshold of a courtyard to enhance the sense of transition from the ordinary to the sacred. These examples show a departure from direct historical forms (no one is rebuilding Topkapı’s style exactly), but a convergence in principles: climate adaptation, spatial layering, and human-scale shelter , which remain at the heart of modern “courtyard” design.

The Latin Courtyard Reimagined: On the other hand, architects inspired by Latin and European traditions have adapted the courtyard to the present day. For example, Mexican architect Luis Barragán incorporated monastery-like and courtyard elements into his work in the mid-20th century. Barragán created enclosed gardens and courtyards with a highly thoughtful character, such as the Capuchin Monastery (Tlalpan Chapel, 1955) and his own home in Mexico City, which he designed through a modern minimalist lens, evoking “peaceful, monastic spaces.” He used long, flat walls painted in vibrant colors to enclose the courtyards, often featuring a shallow water basin or a solitary tree that evoked a blend of Mexican and Mediterranean heritage. This effect resembles a monastery or a Spanish-Moroccan courtyard: silence, sunlight, and a place for inner reflection, yet rendered in modernist geometry. Barragán’s courtyards carry Latin influences with their aesthetic joy and openness to the sky, but they also reflect the inner spirituality of the courtyard (Barragán was indeed extremely religious and admired the tranquility of monasteries). This kind of cross-pollination shows how modern design often combines two traditions—the courtyard becomes a universal symbol of tranquility that draws on both: a love of Latin proportion and a sense of Islamic seclusion. The Swiss architect Mario Botta, known for his strong geometric forms, has also explored courtyard-like designs. In some of his works (such as the atrium of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art or various church projects), Botta creates central voids and atriums that provide light and focus in large structures, functioning like passageways. While these spaces are not always open-air courtyards (they are typically enclosed with glass), they draw on the concept of a closed central space. Botta’s religious buildings, such as the Church of St. John the Baptist (Mogno, 1996), do not have a real courtyard, but they include vestibules and forecourts that evoke the psychological pause of a monastery courtyard or an Italian church courtyard. We can also consider the trend of courtyard-style residential blocks in Europe and America: contemporary urban design often uses a block with an inner courtyard to create community space in dense cities (a model historically common in Barcelona or Berlin). Architects are now ensuring that these courtyards feature greenery, shared gardens, and even fountains—essentially bringing back the Mediterranean courtyard concept for sustainable, communal living. Such designs combine the social focus of the Latin courtyard (neighbors gathering around a shared garden) with climate adaptations (using courtyards for ventilation and cooling) similar to Islamic tradition.

Global Hybrids: Perhaps the most fascinating are projects where both elements are consciously blended. Some modern architects in the Middle East and North Africa are combining the Islamic courtyard heritage with Western design education. For example, new government buildings and universities in the UAE and Iran often feature courtyards with Islamic-inspired shading devices in addition to more international materials. Another area of convergence is residential architecture—boutique hotels in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern contexts often incorporate courtyards that pay homage to local history (such as a riad in Morocco or a palazzo in Italy). These spaces are designed for tourists to enjoy—hence they often combine both the lush intimacy (planted corners, bubbling fountains) and the grand symmetry of European courtyards (formal pool layouts or classical columns), all for ambiance. The revival of riad hotels in Morocco or courtyard boutique hotels in Spain is a good example of this—architects have restored old courtyard houses with modern comforts, transforming them into cosmopolitan spaces where East and West truly meet under the open sky.

Finally, as sustainability becomes a priority, architects around the world are rediscovering the courtyard as a climate solution. This is leading to a convergence: regardless of its stylistic origins, a courtyard can significantly reduce energy needs by promoting cross ventilation, providing shaded open space, and encouraging social interaction without air conditioning. As a result, we are seeing contemporary architecture in places as diverse as California, China, and Australia return to the courtyard typology—not necessarily as a courtyard or monastery, but as a timeless strategy. In some designs, inspiration from both is clearly evident: for example, a mosque in Australia may feature a courtyard inspired by the Prophet’s Mosque (Islamic history), yet also be arranged with gardens reminiscent of local monasteries or campus quadrangles—a true hybrid for a multicultural society.

Convergence or Divergence? In modern adaptations, we observe both divergence (the separate development of each tradition) and convergence (blending). Ottoman-inspired designs continue to prioritize privacy, shadow, and water—but now often with a minimalist or abstract aesthetic. Latin-inspired designs continue to celebrate symmetry and social life—but now often with a more ecological and intercultural sensitivity. In many contemporary projects, when entering a courtyard, echoes of both an Islamic garden and a Mediterranean courtyard can be felt, but they are indistinguishable from one another—this is proof of the universal appeal of a central open space in design. One thing is clear: architects are using courtyards for their long-standing strengths, such as climate flexibility, social harmony, and spiritual beauty. In an age of glass skyscrapers and air-conditioned towers, the revival of courtyards—whether called courtyards, verandas, atriums, or quads—demonstrates a reconnection with timeless, human-centered design wisdom.

The Ottoman courtyard and the Latin courtyard, born out of different climates and cultures, can be seen as two variations on a theme: how to carve out a piece of sky and how to incorporate it into daily life. The differences between them—the courtyard’s open-air forum versus the courtyard’s inward-looking cool oasis, the courtyard’s proud symmetry versus the courtyard’s hidden thresholds—all reflect the deeper values of the societies that created them. One is not “better” than the other; rather, each has achieved a remarkable harmony between people, space, and faith. The Islamic courtyard has transformed harsh environments into secret gardens and aligned homes with an ethical compass of humility and devotion. The Western courtyard, on the other hand, has turned architecture into a stage for human ideals of proportionate beauty, whether monastic contemplation or public sociability. Ultimately, both types aimed to create a paradise on earth: the first, a hidden paradise of shade, water, and faith; the second, a harmonious paradise of order, nature, and community. Today’s architects, when redesigning courtyards, are in a sense reconciling these paradigms—seeking spaces that are both private and communal, climate-conscious, and aesthetically sublime. When we step from a noisy street into a quiet courtyard—whether it is a courtyard in Istanbul, a monastery in Florence, or a modern courtyard in Los Angeles—we cross a threshold into a permanent human refuge. Under an open sky surrounded by old or new walls, we experience what our ancestors intended: relaxation, connection, and perhaps a moment of transcendence. Ottoman and Latin courtyards are siblings speaking a common architectural language that remains relevant in the 21st century as it was in past eras.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.