Architecture is not merely what we see. It is also the silent systems, careful arrangements, and felt atmospheres that shape our lives without drawing attention to themselves. The tradition behind this idea encompasses a conservation ethic that supports restraint, small urban movements that create a ripple effect, and design philosophies that deem objects insignificant in order to bring life to the forefront. Juhani Pallasmaa’s reminder that architecture should appeal not only to the eye but to all the senses is central to this approach. So is the pragmatic view that buildings are composed of layers that change at different speeds, most of which are hidden in walls, ceilings, and floors.

Invisible architecture is not about disappearing. It is about shifting authorship from object to experience, from exhibition piece to support system. Consider quiet renovations that reduce energy consumption without a new façade, street parks that improve the street with a single sensitive addition, or additions that preserve communities in place rather than tearing down and rebuilding.

Definition of the Concept

Invisible architecture refers to design actions that work in harmony with what already exists, minimize disruptions, and enhance quality of life through subtle methods. It seeks advantages in small or hidden movements: adjusting acoustics, light, and temperature; clarifying how the space is perceived; adding soft layers that expand usability without drawing attention. It prioritizes continuity over ostentation.

This concept appears in various fields. In heritage studies, it is associated with minimal, understandable, and reversible interventions. In urban planning, it aligns with Jaime Lerner’s concept of “urban acupuncture,” where precise interventions trigger broader renewal. In terms of productivity, Kengo Kuma’s concept of “anti-object” in modest architectural theory advocates for the removal of autonomous objects to bring the environment and human activities to the forefront.

The historical roots of “invisible” interventions

The conservation movement codified restrictions. The Venice Charter (1964) established principles that still frame sensitive work: respect for the original structure, clarity and scale between old and new, additions that do not disrupt colour or composition. By imposing careful limitations on restoration, prioritising recognisable yet harmonious integration over stylistic uniformity, it encouraged conservation as an ethical duty.

Jaime Lerner popularised the concept of “urban acupuncture” by arguing that small, well-placed actions at the city level can improve larger systems. Examples range from intimate pocket parks like Paley Park to the removal of harmful infrastructure or the revitalisation of markets. The key is sensitivity, speed, and a spark that spreads outward on a human scale.

In theory and practice, architects have also questioned the dominance of objectivity. Kengo Kuma’s concept of “Anti-Object” advocates for prioritizing light, air, and context over isolated form by weakening the architectural object. This approach guides designers toward porous, integrated, and often visually serene outcomes.

Meanings: literal and figurative invisibility

In the truest sense of the word, invisibility refers to interventions that are not immediately visible. Services, insulation, acoustic treatments, smart controls, and light structural reinforcements are located behind walls and ceilings. Stewart Brand’s cut-layer model, developed from Frank Duffy’s work, helps organize these hidden parts according to their different lifespans: the site and structure are permanent, while services and floor plans change frequently. Design that takes these layers into account can improve performance while maintaining a consistent appearance.

Metaphorical invisibility describes a design that refuses to draw the user’s attention. Pallasmaa advocates for a multi-sensory architecture where material, light, sound, and temperature create an “atmosphere” that supports daily life rather than distracting from it. Its value lies in experiential clarity and tranquility. People remember how a place feels rather than how it looks.

A powerful example of this is the conversion of the Grand Parc social housing complex in Bordeaux by Lacaton & Vassal with Frédéric Druot and Christophe Hutin. Instead of demolishing, they added deep winter gardens and balconies while tenants remained in place, improving light, space, and energy performance without increasing rent. This strategy is socially discreet yet spatially generous, winning the 2019 EU Mies Award.

Basic principles and criteria

Restriction and clarity

Interventions should be as light as possible and clearly distinguishable from the original without damaging the scale or composition. This balances honesty with common sense and is consistent with the long-standing principle of conservation.

Layer literacy

Treat buildings as layered systems. Prioritize upgrading rapidly changing layers such as services and floor plans first, avoiding unnecessary disruption to the structure and facade. This allows you to focus on areas where the impact is greatest and disruption is minimal.

Pre-visual atmosphere

Prioritize comfort, touch, sound, and light quality over visual novelty. The goal is not to create an object that competes for attention, but rather an environment that supports daily rituals and well-being.

Leveraged sensitivity

Opt for small, strategic moves that trigger broader change in the urban fabric. Pocket parks, revitalized markets, and micro-infrastructure can reinvigorate streets and communities with modest means.

Generosity and Continuity

When additions are needed, make them work for and with residents. The transformations in Bordeaux demonstrate how additions can expand life while preserving community bonds and budgets.

Why is invisibility important for architects and users?

- It preserves heritage and context. Minimal, legible additions preserve the originality and shared memory embedded in buildings and streets, aligning the design with a public ethic rather than a special display.

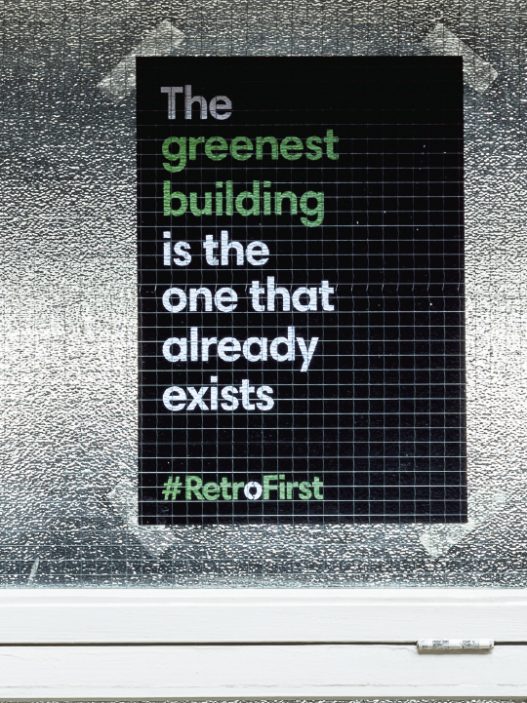

- It reduces interruptions and waste. Working in layers enables upgrades that are faster to implement, easier to maintain, and have a lower carbon footprint compared to a full overhaul. Hidden improvements to services and envelopes typically provide the greatest comfort gain per intervention.

- It puts the human experience at the center. It creates spaces that feel multi-sensory, calm, supportive, and socially generous. When a project improves light, sound, temperature, and usability without drawing attention to itself, people live better.

- It shows how small things can have a big impact. Urban acupuncture proves that subtle and humane gestures can revitalize entire neighborhoods, demonstrating that change doesn’t have to be big, loud, or expensive to create transformation.

- Finally, it keeps communities intact. The Bordeaux example demonstrates how adding rather than removing can expand life without disrupting the social fabric. This ethical and economic gain explains why this approach has earned Europe’s highest honor.

Strategies and Techniques

A palette to visually calm buildings

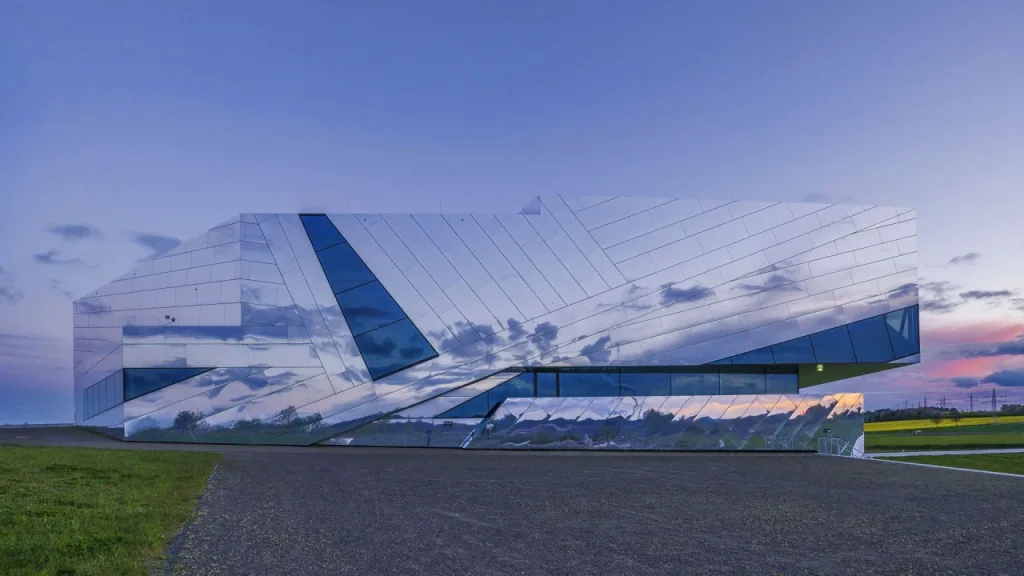

Invisible architecture uses materials and geometries that borrow a space’s colors, reflections, and rhythms to pull objects into the background and bring landscapes to the forefront. Tactics range from mirror coatings that reflect the sky and vegetation, to low-contrast envelopes, vegetated roofs, and sunken courtyards that add volume to the topography. The best works lower their voice rather than disappearing, allowing the context to speak.

Not tricks, but systems

Behind this effect lie systems that regulate light, view, heat, and acoustics. Mirrored or polished finishes expand the horizon; semi-transparent layers blur the edges; sets and cuts conceal volume; precise openings regulate daylight. These are environmental tools as much as visual strategies, and are clearly seen in projects such as SANAA’s reflective Louvre-Lens project, where polished aluminum panels reflect the park, visually “continuing” the landscape throughout the museum mass.

The Ethics of Disappearance

Invisibility is never merely a cosmetic element. It may be necessitated by ecological constraints or urban courtesy, but it also brings certain obligations: glare control, heat management, bird safety, and legibility for users. Cities are now regulating glass to reduce bird strikes and mandating the use of bird-friendly materials on the lower sections of large facades. Collision science shows that reflections and transparency conditions are the main risks, and that visible patterns and lighting controls significantly reduce the harm.

Use of reflective and mirrored surfaces

What is it and how does it work?

Mirrors and high-gloss coatings display buildings as organized elements within their surroundings. This technique merges figure and ground: the object becomes a lens that multiplies the sky, the landscape, and movement. At the Louvre-Lens, the shiny aluminum coating reflects the park, softens the building’s outlines, and visually unites the museum with the landscape.

Techniques and performance considerations

Surfaces vary from mirror glass to bright anodized aluminum. Flat planes provide a clear horizon line continuity; curved or angled planes blur reflections and eliminate volume. Maintenance, glare, and heat gain should be managed through coatings and shading. Importantly, mirrored or transparent glass requires bird-safe detailing, as mandated by codes such as New York City’s Local Law 15, which mandates the use of bird-friendly materials in significant facade areas.

Examples

Doug Aitken’s work titled Mirage, a farmhouse entirely covered in mirrors, disappears into the California desert and transforms the landscape into a “facade.”

In Joshua Tree, Tomas Osinski’s work titled Invisible House expands this idea to the scale of a residence with a long, mirrored prism that reflects the rocks and the sky.

The Sumida Hokusai Museum in SANAA uses light-reflecting aluminum panels to soften the mass while capturing the changing urban light. Each project presents reflection not as an innovation, but as a contextual drawing.

Camouflage, texture and material imitation

Reading the site through texture It is a scale, texture, and pattern adapted to a specific biome. Architects use earth tones, printed or textured cladding, and plant-covered roofs to blend buildings into their surroundings, so that it is not the silhouettes of the buildings but their shadows and textures that define the perception. The Biesbosch Museum Island in the Netherlands achieves this with its earthworks and grass-covered roof, serving as a venue for exhibitions while also being read as a land art piece.

Material strategies

From living roofs to compacted earth and embossed or printed facades, the palette is quite broad. Herzog & de Meuron’s Ricola Kräuterzentrum building is cast from locally sourced earth elements, and its mud walls appear less like foreign objects and more like a geometric section of the landscape.

Examples

STPMJ’s work titled Invisible Barn uses mirror film to cover a simple wooden frame, creating the illusion of an uninterrupted view of the enclosure and making the object appear ghostly.

The Biesbosch Museum Island’s plant-covered roof obscures the building and grounds throughout the seasons, while Ricola’s plant center connects the production to the earth-toned mass and local soil. Together, they present camouflage as a spectrum ranging from true reflection to material similarity.

Underground and soil-integrated forms

Hiding mass within the section

Placing volume below ground level or on sloped areas reduces the visible scale and preserves sightlines. Sunken courtyards, stepped roofs, and protected cut-outs provide air, light, and orientation while allowing the landscape to remain visually dominant. BIG’s TIRPITZ museum carves four linear courtyards into the sand dunes, revealing the gallery network beneath while keeping the shoreline wild.

Daylight and readability underground

The invisible mass is useful in preventing visitors from losing their way. Courtyards, light wells, and clerestory windows make underground spaces intuitive. Tadao Ando’s Chichu Art Museum is mostly built underground to avoid disrupting the island landscape, yet it is illuminated by carefully controlled natural light. Glenstone’s Pavilions place galleries within an elevated structure, with rooms arranged around a light-filled water courtyard to facilitate navigation.

Examples

Villa Vals conceals a fully panoramic residence by opening a circular void into the Alpine slope. Doshi’s Sangath project in Ahmedabad buries vaulted studios into the ground to soften the climate and lighten its presence.

On the Danish coast, TIRPITZ transforms a World War II-era bunker site into an uninterrupted dune landscape with hidden galleries beneath. Different landscapes, same idea: removing volume to bring the space to the forefront.

Light, shadow, and transparency manipulations

Light as structure

In invisible architecture, light draws. Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum draws daylight in through narrow skylights and distributes it with wing-shaped aluminum reflectors, so the galleries shine without visible fixtures. The ceiling appears like the sky, and the building’s tectonics recede behind the artworks.

Degrees of transparency

Transparency is not a binary concept. Ranging from transparency to translucency and reflectivity, each adjusts the perception of proximity and depth. SANAA’s Glass Pavilion at the Toledo Museum uses layered glass walls and courtyards to allow views to flow through space, blurring the boundary between gallery, park, and sky.

Philip Johnson’s Glass House, designed to observe the landscape, transforms the space itself into the primary surface of the architecture.

Shadow, hole, and the choreography of shadow

Perforated canopies and curtains create dynamic patterns that visually lighten the mass. At Louvre Abu Dhabi, Jean Nouvel’s 180-meter dome transforms sunlight into a “rain of light”; a microclimate of dappled shadows that makes the museum feel like a medina of shadows. Light becomes the facade; the structure recedes into the background.

Environmental warning

Transparent and reflective tactics should take ecology into account. Research shows that daytime reflections and transparent conditions are the main causes of bird collisions; regulations now require the use of visible patterns or materials to make glass visible to birds. Invisible architecture works when it is visually calm for humans and clearly visible for wildlife.

Technologies and Innovations

Invisible architecture is increasingly being brought to life with technologies that shift the focus from the object to performance. The most effective systems are those that are unobtrusive yet active in the background, combining materials science, sensing, and computing technologies to adjust light, heat, sound, and attention in real time. Electrochromic glass softens glare without blinds, kinetic blinds follow the sun rather than forcing users to adapt, and projectors draw temporary stories onto historic stones without altering a single fixture. These tools expand the designer’s access to the living experience, enhancing service quality while allowing architecture to recede into the background.

Smart facades and adaptive coatings

What are they?

Smart facades are exterior cladding that changes its state according to climate and usage. These include electrochromic glass that changes color on command, double-skinned facades that regulate air in ventilated cavities, and kinetic blinds that open and close with the sun. Together, they transform buildings from static shells into environmental tools. Authoritative reviews and guidelines frame this field around thermal buffering, natural ventilation potential, and integrated control strategies with building management systems.

How do they work and why are they important?

Electrochromic glass controls sunlight and glare while preserving the view, enhancing comfort, and reducing HVAC demand. Recent federal reports and manufacturer studies document energy and health benefits when control logic coordinates tint, daylight, and glare thresholds. Similarly, double-glazed facades soften peaks, reduce noise, and support mixed-mode ventilation when climate permits by using a second layer and cavity. Performance depends on careful control and detailing appropriate for acoustic properties.

Examples and warnings

The Al Bahar Towers in Abu Dhabi use computer-controlled mashrabiya as a second layer of cladding. Thousands of triangular units in each tower fold according to the sun’s position, reducing the effect of sunlight without blocking the view outside. Engineering partners report a significant reduction in solar energy gain when the system is active, demonstrating how cultural form and climate control can be combined. As such systems increase complexity, reliability, ease of maintenance, and bird-safe detailing remain fundamental responsibilities.

Digital projection and illusion systems

What is it?

Projection mapping aligns light with architecture with millimeter precision. Designers scan or model facades, “mask” surfaces in software, and play content through high-lumen projector arrays, making stone appear to breathe, figures walk along cornices, and structural depth seem optically rewritten. This is a reversible environment that can animate heritage without making physical changes.

Optics, workflows, and range

Workflows combine 3D scans or precise measurements with specialized playback systems and content engines. Large cultural projects use dozens of projectors to produce continuous, high-contrast images and are sometimes integrated with sensors for audience interaction. Case studies document museums built with projection and sensing; in these museums, rooms respond in real time to visitors’ movements and proximity.

Applications and responsibilities

From Gaudí’s Sagrada Família to national art venues, projection has become a readable urban narrative tool on an urban scale. It can highlight craftsmanship, mark the seasons, or simply turn architecture into a public canvas. Permits, impacts on the space, and light pollution require careful planning to ensure the display supports rather than overwhelms the space.

Parametric design and computational blending

What is it?

Parametric design enables geometry to adapt to changing performance targets by linking it to rules. When combined with multi-objective optimization engines, designers can balance daylight, glare, energy, views, structure, and cost within a single decision loop. The goal is not the shape itself, but a design that is compatible with its context and climate.

Toolchain and Methodology

Within Rhino and Grasshopper, the Ladybug Tools package connects models to Radiance and EnergyPlus for daylight and energy simulation, while plugins such as Octopus and Karamba3D investigate trade-offs and adjust structural sections. This stack improves the quality of early stages by keeping feedback within the modeling domain and makes invisible performance readable to the design team.

Evidence and results

Peer-reviewed studies show that multi-purpose workflows can increase daylight autonomy while reducing energy consumption and controlling glare, and can produce envelopes that are perceived as quiet simply because they are functional. Structural optimization examples demonstrate similar gains in material usage and deflection control, allowing designers to conceal efficiency within seemingly effortless forms.

Sensing systems and responsive architecture

From sensors to building behavior

Responsive architecture enables buildings to adjust themselves by combining environmental sensing, control, and actuation capabilities. Classic examples include Jean Nouvel’s Institut du Monde Arabe, with its camera-like eyes that regulate light, and Toyo Ito’s Tower of Winds, which transforms wind and sound into light patterns. Contemporary applications extend this logic through building standards that define high-performance control sequences for HVAC and ventilation.

Standards and durability

ASHRAE Guide 36 formalizes sensor-based sequences that enhance efficiency and comfort in common systems. Recent additions incorporate outdoor air pollution modes and humidity protection measures to enable buildings to maintain indoor air quality during wildfire smoke or excessive humidity events. This coded logic transforms sensors into applicable, repeatable building behaviors rather than specific scenarios.

Implementing digital twins

Research and applications converge on creating digital twins that continuously monitor data from sensors and feed it into models for prediction and fault detection. Reviews and case studies demonstrate how twins support operations and energy resilience, and how they translate invisible performance into a manageable, visual environment for owners and operators.

Sensitivity presented to the public

Media active envelopes and pneumatic coatings transform perception into public experience. Projects such as Barcelona’s Media-TIC project adjust ETFE cushions according to the angle of the sun, while kinetic facades such as Kiefer Technic’s showroom continuously reshape porosity through movable panels. These examples showcase sensitivity not merely as a display, but as an environmental tool that makes the mass lighter and the interior more stable.

Case Studies and Examples

Quiet architecture is best understood through sensitive works that emphasize the environment, light, and use. The following examples demonstrate how reflection, earthworks, street-scale arrangements, and long-lasting renovations can make architecture visible yet visually restrained.

Mirrored pavilions blending with nature

What do they show?

Mirrored envelopes reflect the scenery back onto themselves. When carefully positioned and detailed, the object’s outer lines soften and become part of the surrounding composition.

Case summaries

- Invisible Barn, STPMJ. The barn-shaped wooden frame, covered with reflective film, transforms a shelter into its own facade, creating a camouflaged folly that changes with the seasons.

- Mirrorcube, Treehotel. Located in Harads, Sweden, this 4 x 4 x 4 meter cube covered in mirrored glass floats among pine trees, blending the sky and treetops, while its plywood interior frames a 360-degree view.

- Mirage, Doug Aitken. For Desert X, a completely mirrored suburban house becomes a tool of perception that absorbs and reflects the desert, erasing the boundary between object and space.

- The Invisible House, Joshua Tree. A long prism covered in mirrored glass reflects the rocks and sky on its surface, allowing us to perceive the house as terrain and light rather than volume.

Buildings that are submerged or partially buried

What it shows

Buildings can preserve horizons, sand dunes, and gardens by concealing mass in sections and revealing voids through courtyards and cuts, while remaining intuitively navigable.

Case summaries

- TIRPITZ, BIG. Four pits dug into the sand dunes form an “invisible museum” next to a World War II shelter. Glass roofs allow daylight into the underground galleries without disrupting the profile of the sand dune.

- Chichu Art Museum, Tadao Ando. The spaces in Naoshima, mostly located underground, receive controlled daylight, allowing artworks and seasons to be enjoyed without disrupting the island’s landscape.

- Glenstone, The Pavilions. The galleries, set on an elevated platform, are arranged around a water courtyard adorned with plants. Thus, while performance objectives are quietly achieved, the landscape and art take center stage.

- Villa Vals, SeARCH + CMA. A circular facade carved into the mountainside conceals a residence with full valley views, minimizing the impact near Zumthor’s baths.

Urban projects that minimize visual impact

What it shows

In dense contexts, the least noticeable action can be the most transformative: place most of the program underground or redesign the street space with lightweight, recyclable materials.

Case summaries

- Apple Fifth Avenue, New York. A public square surrounded by trees and linear fountains is encircled by a small glass cube that illuminates the expanded store below. Since most of the urban area is underground, the city skyline is clearly visible.

- Pedestrianization of Times Square. Closing the diagonal section of Broadway to vehicular traffic and constructing simple plazas significantly increased safety and comfort by minimizing the number of permanent objects, and was later formalized as a capital project. Evaluations documented a decrease in injuries and an improvement in pedestrian flow.

- Paley Park, Midtown. This park, which fits into the pocket of an original jacket, demonstrates how a narrow space, a waterfall, trees, and movable chairs can create an urban sanctuary in an area of 0.4 hectares.

A project combining invisibility and sustainabilityeler

What it shows

Restrictions are generally compatible with performance. Upgrades that preserve the existing structure, conceal the mass, or integrate with the ecology can provide social, energy, and carbon benefits without creating visual noise.

Case summaries

- Grand Parc, Bordeaux, by Lacaton & Vassal with Druot and Hutin. Instead of demolishing the building, the team improved light and thermal comfort by adding deep winter gardens and balconies. This allowed residents to continue living in their homes without rent increases. The project won the 2019 EU Mies Award.

- EnerPHit retrofits. The Passive House Institute’s EnerPHit standard certifies deep retrofits through component or demand pathways, enabling phased upgrades that enhance comfort and reduce energy consumption with minimal external alterations.

- Sainsbury Laboratory, Cambridge, Stanton Williams. A low-rise limestone building with controlled daylight and 1,000 square meters of photovoltaic area, it quietly stands within the Botanic Garden and achieved a BREEAM Excellent rating.

- Biesbosch Museum Island, Studio Marco Vermeulen. The roof, composed of earthworks and grasses and herbs, adds ecological value by integrating the museum into the freshwater tidal landscape while reducing the visible mass.

When considered together, these projects advocate for a non-insistent architectural presence: contextually responsive, generous in experience, and disciplined in how it engages with the city, climate, and time.

Challenges, Criticisms, and Future Directions

Invisible architecture promises a silent power, but it encounters very real limitations in terms of physics, rules, ecology, cost, and culture. The following sections address the main conflicts in this field and the direction in which this field will progress in the future.

Practical and technical limitations

Optics and heat are unforgiving

Concave or mirrored envelopes can concentrate sunlight and create extremely hot spots. London’s 20 Fenchurch Street burned objects at street level before precautions were taken, while Las Vegas’s Vdara caused burns at the poolside due to focused reflections. These are cautionary tales about solar geometry, cladding selection, and shading logic.

Facade systems increase safety and maintenance risks

Double-skin facades offer acoustic and thermal advantages, but when fire spreads to the inner skin, the large voids can act as chimneys, making fire stopping and compartmentalization critical. Designers should follow not only model performance but also current facade fire guidelines and test details. Kinetic cladding and operable shading systems also add moving parts, which increases commissioning and lifetime operation and maintenance risks.

The impacts on wildlife and the night sky are now being regulated

Glass, perceived as habitat or clean air, kills birds due to daytime reflections and the transparency effect. Cities like New York are seeking solutions to this problem with bird-friendly design laws that mandate the use of patterned or textured glass in areas with the highest collision risk. Outdoor lighting should be protected, limited, and timed because nighttime light harms ecosystems.

Integrated systems require robust controls

Invisible upgrades are effective when control sequences are transparent and verifiable. Standardized control logic, such as ASHRAE Guide 36, increases reliability and comfort, and the latest additions update sequences for modern equipment and boundary conditions. Commissioning according to these sequences reduces silent failures in “smart” systems.

It relates to underground, water, exit, and wayfinding

Semi-buried or underground structures eliminate bulk, but intensify demands for drainage, waterproofing, smoke control, emergency exits, and intuitive wayfinding. Accessibility standards such as ISO 21542 also require clear pathways and perceptible information in complex sections.

Ethical and perceptual concerns

When disappearing becomes a form of exclusion

“Hostile architecture” conceals social control behind seemingly neutral details, from benches that prevent resting to sharp edges that keep people away. These tactics are subject to fierce criticism because they are concerned with controlling visibility rather than meeting needs, undermining the civic legitimacy that invisible architecture seeks.

Greenwashing risk

Silent envelopes, greenery, and smart optics can be used to market sustainability without delivering measurable performance. Editors and researchers warn that the profession must separate credible full-life-cycle carbon studies from decorative claims and publish transparent data.

Data, sensing, and consent

Smart buildings collect usage and behavioral data. Research and advocacy groups indicate that privacy risks exist when sensing lacks consent, minimization, and governance. Security guidelines exist for IoT networks and privacy-preserving sensing approaches, but these should not be assumed, must be specified, and should be audited.

Originality in interpretation

Projection mapping and digital overlays can tell powerful stories about heritage fabric without touching the stones, but digital heritage experts advise paying attention to authorship, accuracy, and community context so that spectacular images do not overshadow meaning.

Balancing invisibility with user experience

Readability first

Invisible architecture should never be unreadable. Universal Design principles, particularly perceptible information and simple, intuitive use, wayfinding, contrast, tactile cues, and multi-modal communication, provide a practical checklist. Use them to prevent the clarity of serene aesthetics from being compromised.

Make the hidden visible in important places

Bird-friendly signs placed at eye level and around landscape reflections reduce collisions without altering the overall appearance of the facade. Night lighting can be compatible with dark sky initiatives and curfews, so people feel safe while wildlife and neighbors are protected. To help operators understand how a “silent” system should work, clearly communicate control objectives when switching it on.

Design for failure and maintenance

Determine fail-safe positions for actuators, define replacement intervals for actuators and films, and link all of these to standardized sequences so that future teams can keep performance invisible to users but visible to operators.

Emerging trends and speculative futures

Smarter glass, more careful use

Electrochromic glass is maturing. Research and federal reports detail the gains in energy and well-being when controls are coordinated with daylight and glare thresholds. Savings vary depending on the type of building and its exterior. This argues for selective, performance-based application rather than general use.

Solar energy integrated into the building envelope

Building-integrated photovoltaics are moving from the pilot phase to the framework phase, and IEA PVPS Task 15 is advancing standardization and technical guidance. Expect integrated BIPVs that look like normal cladding, are more color-stable, and have verified output and fire ratings.

Operational intelligence with clearer protective measures

Digital twins connect sensors, simulation, and controls for predictive operations. Reviews conducted in 2024–2025 show momentum toward standard data models and 48-hour predictive control cycles, while also emphasizing governance and cybersecurity as part of the design brief.

Renovation as a priority policy

The lifetime carbon policy in large cities encourages teams to prioritize preservation and renovation over demolition. Guidance provided by London and industry groups enables designers to compare similar scenarios and choose quieter options with lower carbon emissions.

Privacy-first sensing

Academic studies suggest privacy-preserving sensors and permission management that do not perform surveillance in shared spaces. Designers will specify not only what a building senses, but also what it refuses to collect and how it anonymizes data by default.

A shared ethic

The future of invisible architecture hinges on a simple agreement: visually appealing, yet highly responsible. This means measured daylight and energy outcomes, accessible pathways, bird-safe glass, dark sky lighting, transparent controls, and privacy provided through design. When these are achieved, disappearing becomes not a mask, but a service.

References for further reading

Kengo Kuma, Anti-Object; Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin; Grand Parc, Bordeaux on the EU Mies Award archive; TU Delft on cut layers; Island Press and ASLA on urban acupuncture. Louvre-Lens designed by SANAA; Sumida Hokusai Museum designed by Kazuyo Sejima; TIRPITZ designed by BIG; Villa Vals designed by SeARCH + CMA; Sangath designed by B. V. Doshi; Chichu Art Museum designed by Tadao Ando; Kimbell Art Museum designed by Louis I. Kahn; Glass Pavilion designed by SANAA; Philip Johnson’s Glass House. Engineering notes for Al Bahar Towers prepared by Arup; DOE report on electrochromic windows; IEA and CIBSE resources on double-skin facades and building controls; Ladybug Tools and Karamba3D documentation; projection mapping case studies prepared by Moment Factory and teamLab.