Cultural buildings such as museums, theatres and cultural centres are crucial in shaping the urban landscape as landmarks that reflect a city’s identity, history and aspirations. Their placement, scale, visibility and integration into various urban contexts are influenced by the complex interplay of cultural policies, heritage conservation frameworks and urban design strategies.

The Impact of Urban Cultural Policies and Heritage Conservation Frameworks

Paris: Heritage Orientated Urban Planning

In cities with strong heritage protection laws, such as Paris, urban cultural policies prioritise the preservation of historic urban fabric. France’s tradition of architectural conservation, rooted in the work of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc in the 19th century and reinforced by international agreements such as the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, imposes strict regulations on new construction in historic areas.

The Grand Projects initiated by François Mitterrand in the 1980s exemplify this approach. Projects such as the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the Louvre Pyramid were strategically placed to enhance cultural significance while respecting heritage constraints. Conceived as four open books, the Bibliothèque Nationale is positioned to create a symbolic cultural centre that reinforces Paris’ identity as a city of art and knowledge. Similarly, the Musée d’Orsay, the transformation of a historic railway station, demonstrates adaptive reuse to integrate new cultural functions into existing structures.

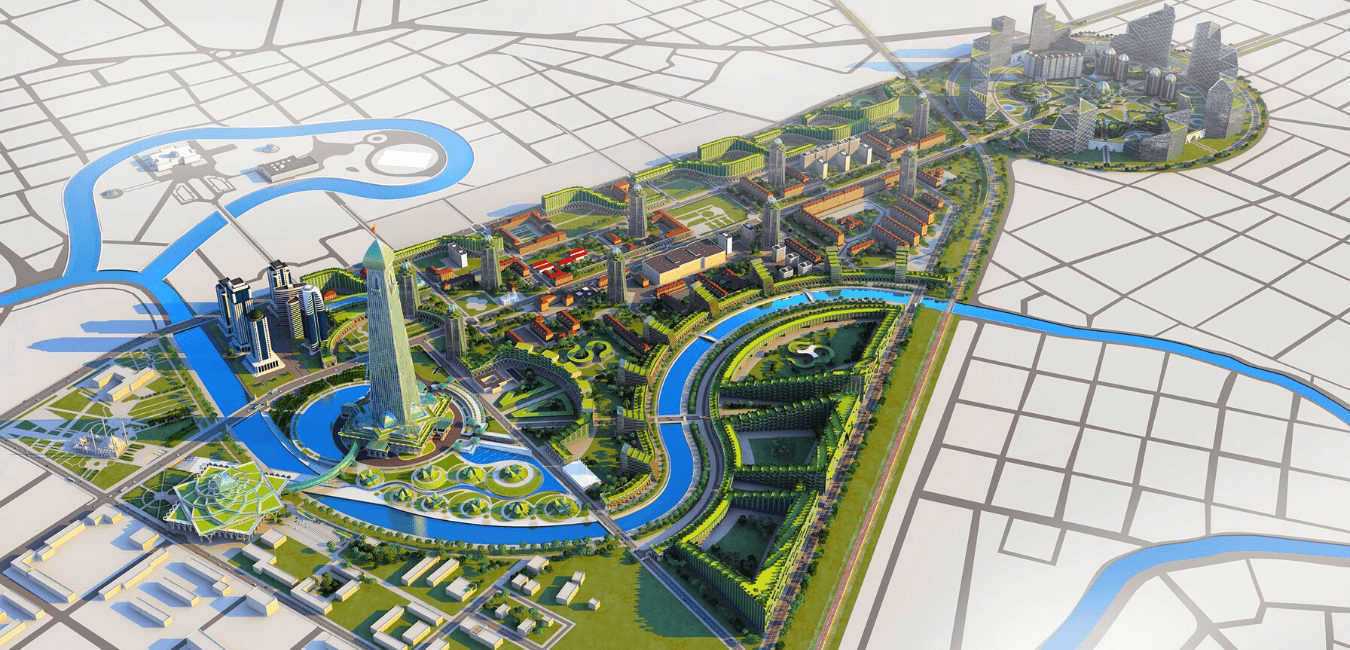

Dubai Development-Oriented Cultural Centres

In contrast, development-oriented cities such as Dubai prioritise iconic cultural buildings to increase tourism and global recognition. The Dubai 2040 Urban Master Plan outlines the goals of developing vibrant communities and preserving cultural heritage, with cultural buildings such as the Dubai Opera and Museum of the Future placed in strategic locations to maximise visibility.

Located in the Opera District near Burj Khalifa, Dubai Opera is designed to be a focal point for cultural exchange and its dramatic view corridors enhance its significance. Located on Sheikh Zayed Road, the Museum of the Future serves as a symbol of innovation with its futuristic design in line with Dubai’s goal of becoming a global centre.

Comparative Analysis

| City | Policy Approach | Placement Strategy | Scale and Visibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paris | Heritage protection | Integration with historical texture | Modest scale, transparent designs |

| Dubai | Development orientated | Strategic placement in new regions | Large-scale, iconic designs |

In Paris, zoning laws and landscape corridor protections limit the scale and siting of cultural buildings to preserve historic aesthetics, while in Dubai policies encourage bold, large-scale design to create new urban identities. These differences reflect changing priorities: economic and touristic ambition versus cultural preservation.

Integration into Historically Layered or Visually Sensitive Contexts

Strategies for Harmonious Integration

Integrating new cultural landmarks into historic or visually sensitive urban contexts requires careful design to avoid disrupting the existing aesthetic or socio-spatial logic. Key strategies include the following:

- Transparency: Use of glass or other transparent materials to maintain visual connections with the historic environment.

- Contextual Massing: To design buildings of a scale and form that complement the existing urban fabric.

- Material Reference: Incorporating materials that reflect local architectural traditions.

- Cultural Metaphors: The use of design elements inspired by local culture or history to create resonance.

- Archaeological Integration: Preservation and display of archaeological findings within the building design.

Louvre Pyramid

Designed by I.M. Pei and completed in 1989, the Louvre Pyramid is a prime example of integrating a modern building into a historical context. Located on the Cour Napoléon, the glass and steel pyramid serves as the main entrance to the Louvre Museum, addressing functional issues while paying homage to the historic palace. Its transparent design ensures that views of the Renaissance architecture are unobstructed, while its simple geometric form contrasts with the ornate surroundings without overwhelming them. Pei’s use of glass was a conscious choice to minimise visual impact, and the pyramid’s alignment with Paris’ historic axis, which extends to the Champs-Élysées, integrates it into the city’s urban narrative.

Acropolis Museum

Designed by Bernard Tschumi and opened in 2009, the New Acropolis Museum in Athens exemplifies integration through transparency and contextual alignment. Located 280 metres from the Parthenon, the museum uses glass facades to provide a visual connection with the Acropolis, allowing visitors to see the historic site from the inside. The top floor, which houses the Parthenon Frieze, is oriented to match the dimensions and alignment of the Parthenon, creating a symbolic dialogue. The museum also houses an archaeological excavation site, where glass floors reveal artefacts, thus preserving and displaying history.

Balancing Innovation and Protection

Both examples show how modern design can coexist with historical contexts by prioritising transparency, respectful scale and cultural references. However, controversies such as the initial opposition to the Louvre Pyramid for its modernist style emphasise the difficulty of balancing innovation with preservation. Architects should guide public and critical perceptions to ensure that new landmarks strengthen rather than weaken urban aesthetics.

City Branding and Its Role in Civic Identity

Global Approaches

Cultural institutions serve as powerful tools for city branding and civic identity, shaped by cultural, political and economic contexts. State-led approaches, such as in Qatar and China, use cultural institutions to promote national identity and soft power, while market-oriented contexts, such as the US, focus on tourism and economic benefits.

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

Designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 1997, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao has transformed Bilbao from a declining industrial city into a global cultural destination. With more than one million visitors a year, the museum plays an important role in stimulating tourism and economic regeneration. Funded by the Basque government, the museum’s iconic titanium-clad design has become a symbol of Bilbao’s reinvention, but some critics argue that it prioritises architectural spectacle over local cultural authenticity.

Qatar National Museum

The National Museum in Qatar, designed by Jean Nouvel and opened in 2019, reflects a state-led approach to cultural diplomacy. Its desert rose-inspired design and integration of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani’s historic palace make it part of Qatar’s heritage, while its modern aesthetic positions Doha as a cultural centre. In its first year, the museum attracted over 450,000 visitors, strengthening Qatar’s global image. Qatar Museums’ policy of combining Islamic and Qatari elements ensures cultural authenticity, but the reliance on international architects raises questions about local representation.

Comparative Analysis

| Region | Approach | Example | Impact on Branding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilbao (Spain) | Market orientated | Guggenheim Museum | Economic regeneration, global tourism |

| Qatar | State-led cultural diplomacy | National Museum | National identity, soft power |

| USA (Los Angeles) | Market orientated | Getty Centre | Civil pride, tourism |

The tension between authenticity and spectacle is evident in these examples. Bilbao’s Guggenheim is celebrated for its economic impact but criticised for overshadowing local culture; Qatar’s National Museum balances local symbolism with global appeal. Successful branding requires the alignment of architectural design with cultural narratives that resonate locally and internationally.

Urban Design Strategies for Connectivity

Principles of Connected Design

Cultural buildings can enhance urban connectivity through strategies that prioritise public access, integration into the urban fabric and community engagement. These include:

- Public Squares and Spaces: Create accessible public spaces around or within the building.

- Adaptive Reuse: Reuse of existing structures to preserve history and integrate new functions.

- Pedestrian Connectivity: Design connections such as bridges or walkways to connect the building to the city.

- Use of Local Materials: Use of materials that reflect the local environment or culture.

- Urban Integration: Positioning the building as a focal point in the cityscape.

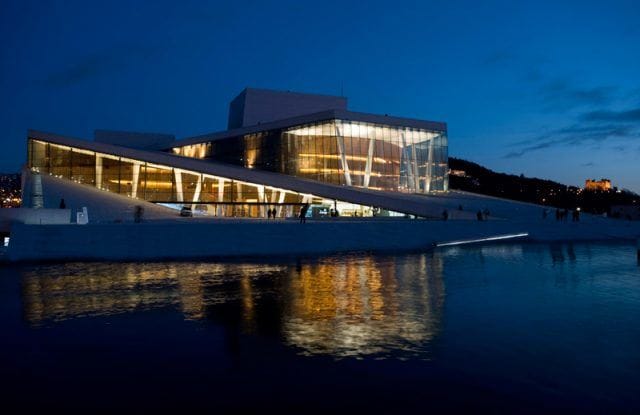

Oslo Opera House

The Oslo Opera House, designed by Snøhetta and completed in 2007, is a model of connector design. Located in the Bjørvika neighbourhood, the building’s sloping marble and granite roof is used as a public plaza, allowing visitors to walk up and enjoy panoramic views of Oslo and the fjord (Oslo Opera House). The building’s design, inspired by the icy Norwegian landscape, integrates with the waterfront, making it a natural extension of the city. Its transparency and accessibility break down barriers between the public and art, encouraging social interaction.

Tate Modern

Housed in a repurposed power station extended by Herzog & de Meuron, London’s Tate Modern is connected to the city via the Millennium Bridge and across the River Thames to St Paul’s Cathedral. The adaptive reuse of the industrial building creates a vibrant cultural centre while preserving London’s history. Public spaces such as the Turbine Hall and free entry to the permanent collection ensure inclusivity, making the museum a community asset.

Increasing Urban Readability

The public roof of the Oslo Opera House and the pedestrian bridge of the Tate Modern create physical and social connections, fostering a sense of community and place.

Ensuring Long Term Urban Sustainability

Challenges of Gentrification

Large-scale cultural developments can trigger gentrification by increasing property values and displacing low-income residents. For example, the High Line in New York has stimulated economic growth but also led to gentrification in surrounding neighbourhoods. To mitigate this, architects and planners should prioritise equity and sustainability.

Strategies for Sustainable Development

- Community Involvement: Involving local residents in planning to ensure that the building meets their needs.

- Affordable Housing: Integrating or supporting affordable housing to preserve existing communities.

- Inclusive Programming: Providing free or low-cost access and community-oriented programmes.

- Sustainable Design: Incorporation of energy-efficient systems and green spaces.

- Comprehensive Urban Planning: Inclusion of the building in a broader strategy addressing social, economic and environmental objectives.

Medellín’s Library Parks

Medellín’s social urbanism strategy includes library parks, such as the Biblioteca España in Santo Domingo Savio, designed to provide cultural and educational resources to underserved communities. Part of a wider urban regeneration plan, these projects prioritised local needs over tourism, reducing inequality and promoting social inclusion.

Copenhagen’s Superkilen Park

Designed by BIG, Superflex and Topotek 1, Superkilen Park in Copenhagen celebrates diversity through community input, bringing together elements from more than 60 nationalities. Its inclusive design and public accessibility provide a model for sustainable cultural spaces that enhance social cohesion.

Avoiding Top-down Approaches

Top-down ‘starchitecture’ projects, such as some iconic museums, can risk gentrification by prioritising vanity over community needs. In turn, inclusive planning, as seen in Medellin and Copenhagen, ensures that cultural structures contribute to equitable and sustainable urban development.

Conclusion

Cultural buildings are more than architectural landmarks; they are catalysts for urban regeneration, identity and connectivity. By navigating the complexities of urban policy, heritage conservation and inclusive design, architects and planners can ensure that these buildings enhance cities without disrupting their social or aesthetic fabric. From Paris’ heritage-driven approach to Dubai’s development-oriented strategy, and from Bilbao’s economic revitalisation to Medellín’s social urbanism, cultural buildings reflect diverse priorities and possibilities for shaping sustainable, inclusive and vibrant urban futures.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.