The 1960s was a period of profound changes around the world, marked by a vibrant countercultural movement aimed at challenging social norms. This period was characterised by the search for freedom, self-expression and re-imagining society. As young people rejected the conformism of previous decades, they embraced alternative lifestyles that spanned a variety of fields, including architecture. To reflect the ideals of the counterculture, architects and designers have begun to design spaces that encourage creativity, inclusivity and communal living, moving away from traditional designs.

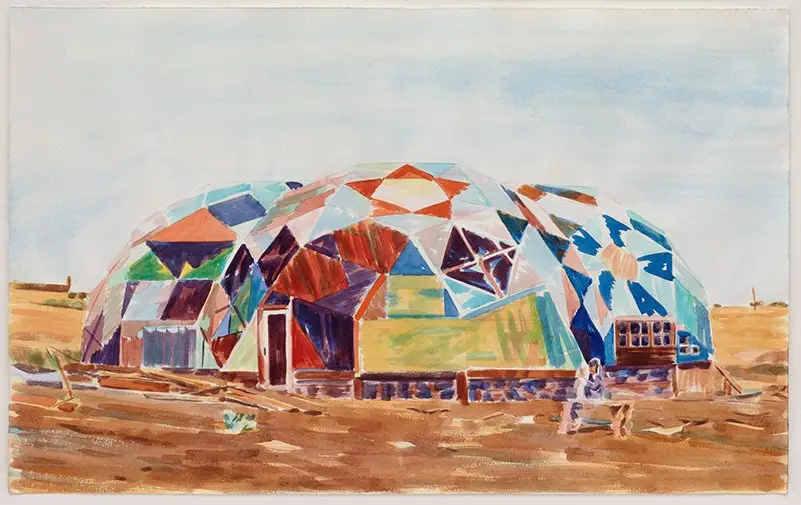

A painting of Drop City in Trinidad, Colorado. Image © Mark Harris

Historical Context

To understand the architectural developments of the 1960s, it is crucial to recognise the historical background. The post-World War II period saw rapid urbanisation and industrial growth, which often prioritised functionality over human experience. By the 1960s, however, social tensions were rising due to civil rights movements, anti-war protests, and growing frustration with government and corporate authority. Amidst this unrest, a strong desire for alternative lifestyles and community-orientated living emerged. This desire has significantly influenced the architectural environment, forcing architects to rethink how spaces can be designed to reflect the values of this new cultural paradigm.

Key Influences on Architecture

There are several important influences that shaped the architectural direction of the 1960s counterculture. The writings of philosopher and urban planner Lewis Mumford emphasised the importance of development on a community and human scale. Mumford’s ideas inspired architects to consider how buildings could enhance social interactions. In addition, the organic architecture movement, championed by figures such as Frank Lloyd Wright, advocated buildings in harmony with their natural surroundings. This approach encouraged the use of local materials and designs that integrate with the landscape, reflecting the counterculture’s respect for nature.

Moreover, the rise of new technologies and materials allowed for more experimental designs. Architects began to play with previously unimaginable forms and structures, leading to innovative designs that focused on aesthetics as much as functionality. This exploration was not just about breaking away from traditional styles; it was also about creating spaces that resonated with ideals of freedom, creativity and community.

Overview of Counterculture Ideals

At the centre of the counterculture movement were the ideals of peace, love and community. These principles were not only a reaction to prevailing social norms, but also a vision of a better world. The counterculture emphasised a holistic approach to life, promoting co-operation over competition and community over individualism. In architecture, this translated into designs that encouraged shared spaces such as communal gardens, open-plan living and collective facilities.

Architects began to envisage buildings as environments that could facilitate social interactions. Spaces were designed to be flexible and adaptable, allowing for a variety of uses and fostering a sense of belonging among users. The idea was to create not just structures, but living ecosystems where creativity can flourish and communities can thrive.

Important People in the Movement

Several architects emerged as important figures during this transformative period. Notable is Richard Meier, whose work, including the Getty Centre in Los Angeles, embodies the spirit of the counterculture in its emphasis on light and openness. Similarly, Charles Moore’s design philosophy, particularly in the Sea Ranch community in California, reflects the ideals of the counterculture. Moore’s designs emphasised integration with the environment and community involvement, creating spaces that were both functional and poetic.

Another influential figure was Paolo Soleri, who introduced the concept of “archaeology”, a blend of architecture and ecology. Soleri’s vision of densely populated, self-sustaining communities challenged traditional urban planning, proposing a new way of living more in tune with the environment and community needs. These architects, among others, played important roles in shaping the built environment in accordance with the ideals of the counterculture.

Influences on Urban Planning

The impact of the counterculture movement of the 1960s on urban planning was profound and far-reaching. It led to a shift towards more participatory planning processes, with communities increasingly being heard in decisions about their own space. Planners have begun to recognise the importance of public spaces, integrating parks and common areas into urban design to strengthen social bonds.

Furthermore, the ideals of sustainable living and ecological awareness have gained traction, influencing urban designs that prioritise green spaces and minimise environmental impact. Concepts such as pedestrian-friendly streets, mixed-use developments and community gardens became more common, reflecting the counterculture’s commitment to nurturing relationships within neighbourhoods.

As a result, the counterculture architects of the 1960s played a crucial role in redefining community and creative spaces. Their work not only challenged the architectural norms of the time, but also set the stage for contemporary debates about sustainability, community-orientated design and the importance of public spaces in urban planning. The legacy of this movement continues to inspire architects and urban planners today, reminding us of the power of design to shape a more connected and cohesive society.

The 1960s was a transformative decade of countercultural movements that challenged the norms of society, art and architecture. This period gave rise to a wave of innovative architects and artists who sought to redefine community life and creative spaces. Their work was not just about building structures; it was about creating environments that fostered connection, freedom and self-expression. As we explore the major architectural masterpieces of this period, we see how they reflect the ideals of community and creativity at the heart of the counterculture.

Important Architectural Masterpieces

The Digger’s Free Shop

One of the most iconic manifestations of the 1960s counterculture was the Digger’s Free Store in San Francisco. Founded by a group of artists and activists known as the Diggers, this space was much more than a store; it was a bold statement against consumerism. The Free Store operated on the principle of the gift, where goods were freely exchanged rather than bought and sold. This radical approach to commerce created a community centre that encouraged sharing and collaboration.

The Free Store’s architecture was deliberately simple and unpretentious and designed to reflect Diggers’ values. It was a space where people from different backgrounds could come together, fostering a sense of belonging and mutual support. The Digger’s Free Store exemplified how architecture can be used as a tool for social change by fostering a culture of generosity and interconnectedness.

Ant Farm’s Cadillac Farm

Ant Farm, a collective of artists and architects, has taken a playful yet provocative approach to architecture with their installation known as Cadillac Ranch. Located in Amarillo, Texas, the artwork consists of ten vintage Cadillacs buried nose-first in the ground, creating a surreal and eye-catching landscape. The installation is a striking commentary on American consumerism and the car culture that dominated the 1960s.

Cadillac Ranch is not only a static work of art; it also invites interaction. Visitors are encouraged to spray paint the cars, allowing the installation to evolve over time. This participatory aspect reflects the counterculture’s understanding of creativity and self-expression. Transforming an ordinary object into a canvas for artistic expression, Ant Farm redefined the relationship between architecture and the public, making art accessible and engaging.

Haight-Ashbury District

The Haight-Ashbury District in San Francisco became the epicentre of the 1960s counterculture movement. Its colourful Victorian houses and lively streets filled with vibrant storefronts reflected the spirit of the era. Architects and urban planners working in the area focused on creating spaces that foster community by taking a more organic and inclusive approach to urban design.

The area was home to numerous gathering points, including cafes, music venues and parks designed to encourage social interaction. Haight-Ashbury’s architecture reflected a mix of styles that symbolised the diversity and creativity of its residents. Through shared spaces, the neighbourhood has become a refuge for those seeking alternative lifestyles and artistic expression, demonstrating how architecture can shape cultural movements.

Black Mountain College Campus

Black Mountain College in North Carolina was an experimental institution combining art, education and community life. Founded in the 1960s but flourishing in the 1960s, the college attracted renowned artists and thinkers, including Buckminster Fuller and Merce Cunningham. The campus itself was designed as a collaborative space where architecture plays a crucial role in fostering creativity.

Buildings at Black Mountain College are often constructed using local materials, emphasising sustainability and connection to the environment. The design encouraged interaction between students and faculty, fostering an atmosphere of experimentation and dialogue. This approach to architecture not only served educational purposes, but also provided a model for how spaces can be designed to enhance learning and creativity.

Simple Living Architecture

The concept of Simple Living Architecture emerged as a reaction against the excesses of modern life. Architects and designers have endeavoured to create homes and spaces that are not only functional but also environmentally sustainable and minimalist. This movement has emphasised the importance of living simply and in harmony with nature.

Simple Living Architecture often features open floor plans, natural materials and a focus on light and space. These designs reflect the counterculture’s rejection of consumerism, promoting a lifestyle that values experiences over possessions. Real-world applications of this philosophy can be seen in eco-villages and tiny house movements that continue to advocate for sustainable living and community-oriented spaces today.

In conclusion, the architectural masterpieces of the 1960s counterculture are enduring evidence of an era in which creativity, community and social change were deeply intertwined. Through their innovative designs and collaborative spaces, these architects not only reshaped the physical landscape, but also inspired future generations to consider the impact of architecture on society. Their legacy lives on and encourages us to explore how our built environments can foster connection, creativity and a sense of belonging.

The 1960s was a decade marked by profound social upheaval and cultural revolution. Amid civil rights movements, anti-war protests and a burgeoning counterculture, architects began to rethink the environments in which people lived, worked and played. This exploration led to a new wave of architecture emphasising community, creativity and sustainability. The architects sought to create spaces that reflect the values of the counterculture, celebrating individuality, co-operation and a deep connection with nature.

Design Principles of Counterculture Architecture

Counterculture architecture emerged as a reaction to the rigid structures of mainstream architecture. It is characterised by several basic principles that aim to foster a sense of community, encourage creative expression and establish a harmonious relationship with the environment.

Community and Co-operation

At the centre of countercultural architecture was the idea of community. The architects recognised that spaces could not only serve functional purposes but also bring people together. Designs often included communal spaces where individuals could come together, share ideas and collaborate on projects. This emphasis on community manifested itself in a variety of architectural forms, from shared housing projects to open-plan layouts in public buildings.

For example, Sea Ranch in California, developed by a group of architects and designers, exemplified this principle. It included not just isolated structures, but homes that were part of a larger community and encouraged interaction between residents. The idea was that improving relationships would lead to stronger, more vibrant neighbourhoods.

Rejection of Traditional Aesthetics

Counterculture architects deliberately distanced themselves from established design norms. They believed that traditional architectural styles were often elitist and disconnected from the realities of everyday life. Instead they adopted eclectic forms, combining different styles and materials to create unique structures that reflected the diversity of the communities they served.

Buildings from this period often exhibited playful shapes, bold colours and unusual materials. For example, the work of architect Robert Venturi, particularly his design for the Vanna Venturi House, broke away from the austere minimalism of modernism. Venturi’s designs emphasise complexity and contradiction, celebrating the chaotic beauty of the contemporary world.

Use of Sustainable Materials

As awareness of environmental issues began to grow, counterculture architects sought to incorporate sustainable practices into their designs. By favouring locally sourced and environmentally friendly materials, they reflected a growing awareness of the impact of construction on the planet.

The use of reclaimed wood, natural stone and other sustainable materials has become widespread as architects aim to minimise their ecological footprint. Ecovillage in Ithaca, New York is an excellent example of this commitment. Houses built with sustainable materials and emphasising energy efficiency show how architecture can harmonise with ecological principles.

Flexibility in Space Utilisation

Another defining characteristic of countercultural architecture was the emphasis on flexible spaces. The architects recognised the need for environments that could adapt to the changing needs of the residents. This flexibility allowed for multifunctional spaces that could serve a variety of purposes throughout the day.

For example, community centres designed during this period often incorporated movable walls and adaptable layouts, enabling them to host a range of events from meetings to art exhibitions. This approach has not only increased the usefulness of the areas, but also fostered a sense of ownership among community members as they are able to reshape their environment according to their own needs.

Integration with Nature

Finally, countercultural architecture sought to create a seamless relationship between the built environment and the natural world. Architects aimed to design buildings that coexist harmoniously with their surroundings and often incorporated natural elements into their designs.

The concept of biophilic design emerged during this period and emphasised the importance of nature in human life. For example, many houses were designed to maximise natural light and ventilation, and the lines between indoors and outdoors were blurred. The work of architect Frank Lloyd Wright, particularly his designs for buildings such as Fallingwater, influenced this movement and inspired architects to prioritise nature in their projects.

As a result, the counterculture architects of the 1960s redefined the way we think about community and creative spaces. Their principles – collaboration with the community, rejection of traditional aesthetics, sustainable materials, flexibility in use and integration with nature – continue to influence contemporary architecture. These visionary architects not only transformed physical spaces, but also inspired a movement that prioritised human relationships and environmental stewardship, leaving a lasting legacy for future generations.

The 1960s was a pivotal decade of profound social change, artistic experimentation, and a burgeoning counterculture that challenged established norms. Among the many voices of this period, architects played an important role in redefining how communities were designed and experienced. The counterculture architects of the 1960s were not just designers of buildings; they designed spaces that fostered connection, creativity and a sense of belonging. This research examines their influence on modern architecture, highlighting their legacy, contemporary practices and enduring principles that continue to shape our environment today.

Influence on Modern Architecture

The architects of the 1960s were deeply influenced by the cultural upheavals of their time. They sought to move away from rigid, traditional design practices and instead favoured approaches that emphasised openness, flexibility and a strong connection to the community. This shift was not simply aesthetic; it was driven by a desire to create spaces that reflected the ideals of peace, love and equality that characterised the counterculture movement.

One of the most important contributions of these architects was their focus on human scale design. Instead of monumental structures that alienate individuals, they advocated accessible and inviting designs. This emphasis on user experience permeated modern architecture, encouraging a more participatory relationship between people and their environment. Today we see this reflected in urban planning efforts that prioritise walkability, mixed-use developments and the inclusion of green spaces that encourage social interaction and community engagement.

Legacy of 1960s Architects

The legacy of the counterculture architects of the 1960s is reflected in the various architectural movements that followed them. Their innovative designs and philosophies paved the way for the emergence of postmodernism and other contemporary styles that embraced eclecticism and a mix of historical references. Architects such as Richard Meier and Robert Venturi integrated these elements into their work, inspired by the playful forms and bright colours that characterised the period.

Moreover, architects of the 1960s advocated a more democratic approach to architecture, emphasising the importance of community input in the design process. This participatory approach continues to influence contemporary design practice by encouraging architects to engage with local communities and consider their needs and aspirations. This legacy has encouraged a more inclusive architectural dialogue that values diverse perspectives and strives to create spaces that resonate with all members of society.

Contemporary Community Spaces

Today, the principles advocated by the architects of the 1960s are reflected in the design of contemporary community spaces. Projects such as community centres, parks and public plazas are designed to bring people together and encourage interaction and collaboration. These spaces often include flexible layouts that reflect the dynamic nature of modern life and can host events ranging from concerts to farmers’ markets.

Moreover, urban designers increasingly recognise the importance of integrating art and culture into public spaces. This approach not only enhances the aesthetic quality of environments, but also fosters a sense of identity and belonging among urban residents. The architects continue the legacy of the 1960s by creating vibrant and engaging spaces that celebrate local culture and emphasise the role of architecture in shaping community life.

Green Architecture Movement

The 1960s counterculture laid the foundation for the green architecture movement that gained momentum in the late 20th century. Architects of this period were among the first to advocate sustainable practices, emphasising the need to harmonise buildings with their natural surroundings. This holistic approach to design considers not only the environmental impact of buildings, but also their social and cultural impact.

Contemporary green architecture aims to minimise ecological footprints through innovative materials, energy-efficient systems and designs that encourage biodiversity. Buildings are now designed as part of a larger ecosystem integrating features such as green roofs, solar panels and rainwater harvesting systems. This shift reflects a growing awareness of environmental issues and a commitment to creating spaces that contribute positively to both people and the planet.

Adaptive Reuse of Historic Sites

Another important legacy of the 1960s counterculture is the practice of adaptive reuse, which involves redesigning existing buildings for new uses. This approach not only preserves historic architecture, but also promotes sustainability by reducing the need for new construction. Many architects of the 1960s recognised the potential of older buildings to serve contemporary needs, leading to a renewed appreciation of heritage and context in architectural design.

Today, adaptive reuse projects can be seen in cities around the world, transforming warehouses into loft apartments, factories into art studios and churches into community centres. These projects breathe new life into underused spaces, creating unique environments that honour the past while embracing the future. Valuing history and creativity, adaptive reuse continues to inspire architects to find innovative solutions that reflect the countercultural spirit of the 1960s.

Public Art and Architecture

Finally, the integration of public art into architectural projects is another enduring aspect of the influence of the 1960s counterculture. Architects began to see art as an essential component of the built environment, enriching public spaces and enhancing community identity. This collaboration between artists and architects has led to the creation of vibrant murals, sculptures and installations that invite interaction and provoke thought.

Contemporary public art initiatives often aim to reflect the cultural and social narratives of their communities and make art accessible to all. Encouraging dialogue and interaction, these projects embody the ideals of the 1960s, promoting inclusivity and shared experiences. As cities continue to evolve, the combination of art and architecture remains a powerful tool for community engagement, reflecting the transformative spirit of the counterculture era.

As a result, the architects of the 1960s were visionaries who challenged traditional norms and reimagined the role of architecture in society. Their influence is evident in modern practices that prioritise social inclusion, sustainability and the integration of the arts. By continuing to explore and expand their legacy, contemporary architects can create spaces that not only meet the needs of today but also inspire future generations.

The 1960s was an important period in history, marked by a wave of social change and a desire for freedom and authenticity. Against this backdrop, a group of architects emerged, motivated by the ideals of the counterculture. They did not just design buildings, but sought to reshape communities and create spaces that foster connection, creativity and inclusivity. Through their innovative approaches, these architects transformed the way people interact with their environment and with each other, pushing the boundaries of traditional architecture in ways that resonate today.

Case Studies on Community Oriented Projects

Omega Institute

Founded in upstate New York, the Omega Institute for Holistic Studies embodies the spirit of the counterculture movement. Its design is based on principles that prioritise well-being, sustainability and community. Set amidst a lush natural environment, the campus is a sanctuary for personal and community development. The architecture blends seamlessly with the landscape using natural materials and organic forms that evoke a sense of harmony.

The focus at Omega is not only to provide a space for workshops and retreats, but to create a community where individuals can explore transformative practices such as yoga, meditation and sustainable living. The design encourages interaction between participants, fostering a sense of belonging and shared experience. This holistic approach has made the Omega Institute a model for similar spaces around the world, demonstrating how thoughtful design can nurture both the individual and the community.

San Francisco’s Community Gardens

In the vibrant city of San Francisco, community gardens have emerged as grassroots responses to urbanisation and food shortages. These gardens are more than just green spaces; they are communal spaces where different groups come together to cultivate not only plants but also relationships. The design of these gardens reflects the principles of accessibility and inclusivity, often including raised beds for those with mobility difficulties, and spaces for gathering and education.

Through community gardens, residents reclaim vacant land and transform it into productive spaces that contribute to food security and environmental sustainability. Serving as educational centres, these gardens teach residents about gardening and nutrition, while fostering a sense of pride and ownership in their neighbourhoods. The success of these gardens highlights the power of collaborative design to address social issues and build community resilience.

Common Ground in New York

Founded in the 1980s, Common Ground has taken a radical approach to the problems of homelessness and housing insecurity in New York City. The organisation focuses on creating supportive housing that not only provides shelter but also creates a sense of community among residents. The architectural design of these spaces emphasises functionality while encouraging social interaction.

Each building is designed with communal spaces such as kitchens and lounges where residents can connect with and support each other. This approach recognises that shelter alone is not enough, creating a supportive environment is crucial to promoting stability and well-being. Common Ground’s success in integrating these principles into their design has inspired similar initiatives across the country, showing how architecture can play a vital role in social change.

Radical Design in Social Housing

The 1960s and 70s witnessed an increase in radical design principles applied to social housing projects. Architects began to challenge traditional notions of housing, prioritising affordability, flexibility and community participation. One notable project is Habitat in Montreal, which redefines urban living with its innovative modular units.

These designs often include common spaces that encourage interaction between residents, such as playgrounds, gardens and community rooms. By moving away from the isolation typically associated with traditional housing, these architects aimed to create environments that strengthen social bonds and provide support networks. This radical approach continues to influence contemporary social housing initiatives, emphasising the importance of design in promoting equality and social cohesion.

Participatory Urbanism

Participatory urbanism represents a transformative shift in the involvement of communities in the design process. Rooted in the counterculture movement, this approach invites residents to actively participate in shaping their environment. It recognises that the people living in a community are best equipped to understand their needs and aspirations.

Through workshops, forums and collaborative design sessions, architects and urban planners can gather invaluable insights from community members. This inclusive process not only leads to more relevant and effective designs, but also empowers residents, giving them a stake in their environment. Successful examples of participatory urbanism can be seen in various cities where citizens are transforming vacant land into parks or revitalising neighbourhoods through collaborative initiatives. By encouraging dialogue and collaboration, this movement continues to reshape urban landscapes, allowing them to reflect the diverse voices of the communities they serve.

As a result, the architects of the 1960s counterculture movement laid the groundwork for a more inclusive and community-orientated approach to design. Their innovative projects and philosophies continue to inspire contemporary architecture and remind us of the profound impact that thoughtful design can have in fostering connection, creativity and social change.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The 1960s was a pivotal moment in the history of architecture, marked by a vibrant counterculture that sought to reshape not only buildings but also the fabric of community life. The architects of this period challenged traditional design norms and embraced ideals of freedom, experimentation and communal living. Reflecting on their contributions, we can see that their profound influence on contemporary architecture and community planning continues.

Reflecting on Countercultural Ideals

The counterculture architects of the 1960s were driven by a vision of a society that prioritised human relationships, creativity and sustainability. They designed spaces that would foster co-operation and encourage a sense of belonging. During this period, innovative designs emerged, such as communal living environments, shared housing and open-plan spaces that break down barriers between individuals. These visionaries rejected the rigid structures of mainstream architecture, advocating a more inclusive design approach that took into account the needs and aspirations of diverse communities.

Their ideals were not merely theoretical; they were often put into practice through projects that served as experiments in social living. For example, the design of communal spaces in neighbourhoods aimed to enhance interaction between residents, creating a sense of shared responsibility and ownership. This reflection of the past reminds us that architecture is not only about physical structures, but also about the relationships and experiences they foster.

Challenges of Community Architecture Today

Despite the rich heritage of the 1960s counterculture, the architecture of modern society faces numerous challenges. Urbanisation and rapid population growth have led to a demand for housing that often prioritises profit over community needs. As cities expand, the essence of communal living can be overshadowed by cookie-cutter developments that lack character and connectivity.

Furthermore, socioeconomic inequalities continue to pose barriers to inclusive design. Many communities struggle to find their voice in architectural debates, leading to developments that do not reflect their cultural identity or needs. The challenge lies in balancing the desire for innovative, community-oriented architecture with the realities of market forces and regulatory frameworks that often prioritise speed and efficiency over human-centred design.

Emerging Trends in Socially Conscious Design

As we navigate the complexities of modern life, some emerging trends indicate a growing interest in socially conscious design. Architects and planners are increasingly focussing on sustainability, integrating green practices that not only protect the environment but also enhance community well-being. This includes designing spaces that support active living, such as parks and pedestrian-friendly areas that encourage social interaction and a healthier lifestyle.

There is also an increasing emphasis on participatory design, where community members play an active role in the planning and development process. This approach encourages a sense of ownership and pride, ensuring that the spaces created truly reflect the needs and desires of those who will use them. Projects utilising local materials and traditional building techniques are also of interest, meeting contemporary needs while celebrating cultural heritage.

The Role of Technology in Future Spaces

Technology is reshaping the way we think about social spaces. Smart technology and data analytics offer new opportunities to design environments that respond to users’ needs in real time. For example, adaptable buildings that can change their function according to the time of day or the number of occupants are becoming increasingly common, creating flexible spaces that can evolve with the needs of the community.

Furthermore, digital platforms facilitate greater collaboration between architects, designers and community members, enabling more inclusive and transparent processes. Virtual reality and augmented reality tools enable stakeholders to visualise and interact with designs before they are built, giving everyone a voice in the creation of their environment. As technology continues to advance, it has the potential to enhance our understanding of how people use space and create more adaptive and responsive environments.

Final Thoughts on Legacy and Impact

The legacy of the 1960s counterculture architects is profound and enduring. Their determination to redefine society through innovative design fuelled movements that continue to influence contemporary architecture. As we look to the future, it is crucial to honour their ideals when addressing the contemporary challenges of urban living.

Adopting a holistic approach that values sustainability, civic engagement and technological advancement can help us create spaces that nurture human connections and reflect the diverse needs of our societies. The influence of these architects reminds us that the built environment can be a powerful agent for social change, shaping not only the physical landscape but also the way we live, interact and envision our shared future.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.