When Language Falls Short, Architecture Speaks

The Power of Untranslatable Words

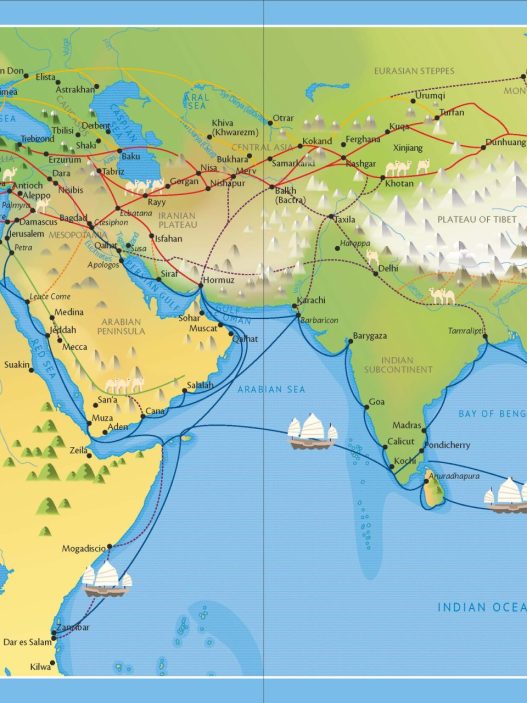

Some cultures invent words for places that others hardly notice: thresholds that slow you down, rooms that teach hospitality, or a “lost” place you still carry in your heart. UNESCO refers to this fabric of living practices and meanings as “intangible cultural heritage,” which encompasses how people use and experience space: what we build, how we gather, where we mourn or celebrate. Architects who listen to these words gain a sharper perspective on the human experience their buildings must accommodate.

Why Should Architects Care?

A single word can serve as a program summary. For example, the word “Meclis” refers to a social room used for hosting guests, consultations, and community ceremonies in the Gulf region; a clear spatial purpose lies within a single name. Designing with the Assembly in mind means planning for the seating arrangement, coffee ritual, wide entrance, and social visibility of the space. This kind of semantic precision is a shortcut to cultural adequacy.

How Does Cultural Semantics Shape Design-Focused Thinking?

Language can indicate spatial logic (such as Japanese ma — meaningful space) or specific structural elements (such as engawa — threshold walkway-veranda). Learning these terms opens up design possibilities: choreographing pauses, thickening thresholds, and giving edges a new social life.

1. “Hiraeth” (Welsh): Longing for a Lost Place

Spatial Nostalgia as a Design Concept

Hiraeth is more than just homesickness; it is a delicate longing for a home, a time, or a feeling that no longer exists or perhaps never did. Think of it as an emotional compass pointing to “the place I belong,” even if the map has changed. As a design lens, hiraeth invites architects to work not only with form and function, but also with memory and absence; it asks how buildings can carry the stories, rituals, textures, and sounds that give people a sense of “coming home.”

In environmental psychology, this lies at the very heart of the concept of “place attachment” — the bond between people and places is shaped by who we are, what we do there, and the qualities of the place itself. Scannell & Gifford’s framework (person-process-place) is particularly useful: it reminds designers that belonging stems from identity and memory (person), emotion and meaning (process), and physical features and environments (place). Designing for hiraeth means valuing all three.

Hiraeth also aligns with UNESCO’s concept of intangible cultural heritage: living traditions, rituals, and meanings, along with the “cultural spaces” that host them. This is a practical tip: architecture can preserve not only the structure but also the social life that gives a place its soul. Courtyards for singing, porches for greeting, kitchens for communal tea drinking… These are the pillars that keep memories alive.

Architectural Responses to Displacement

When people relocate voluntarily or involuntarily, their connection to the place may weaken. Research shows that carefully designed environments can help rebuild belonging and well-being: familiar materials, walkable public spaces, and suitable environments for daily contact support a sense of belonging. For refugees and migrants, even small, understandable spaces for gathering, worship, cooking, and green areas can accelerate the transition from shelter to community.

Design strategies that honor Hiraeth are concrete and repeatable:

- Preserve the traces. Preserve elements such as old walls, rows of trees, and floor patterns, so that there is something for memory to cling to. Heritage guidelines like the Burra Charter recognize not only bricks and stones but also their social and spiritual value.

- Program rituals. Create spaces for recurring practices (Sunday, prayer, tea time, music). These rhythms breathe new life into old identities.

- Design for connection. Environmental psychology links everyday interactions such as sitting, meeting, and walking with stronger bonds; green and public spaces are key in this regard.

Even in temporary environments, respectable arrangements and a “sense of home” are important. Research on camp design argues for the importance of spaces that can develop into permanence or a meaningful routine rather than endless transience.

Case Studies: Design for Emotional Return

Yr Ysgwrn (Trawsfynydd, Wales). Poet Hedd Wyn’s farmhouse, with its furniture, hearth, and domestic arrangement, has been preserved almost entirely as it was in 1917, allowing visitors to take a “journey back in time.” The house, which preserves the fabric of rural life, has become an instrument of collective memory and sorrow, a silent example of hiraeth. The tradition of “keeping the door open” at this place highlights how hospitality and continuity can be incorporated into heritage management.

Welsh Churches in Patagonia (Gaiman & Trelew, Argentina). In Y Wladfa, Welsh settlers reproduced church typologies using local stone and timber and maintained cultural rituals such as the Eisteddfod and community tea gatherings. The architecture here acts as a bridge: familiar Nonconformist forms were adapted to a new landscape, creating places where language, song, and gathering could take root, and where descendants could still feel a living connection to Wales.

Senghenydd National Mining Disaster Memorial Garden (Caerphilly, Wales). Officially recognized as Wales’ National Mining Disaster Memorial Garden in March 2024, this memorial space transforms losses into paths, names, and markers. Offering families and communities a place of return where they can revisit memories of work, solidarity, and grief, this memorial garden demonstrates how public spaces can honor a nation’s sense of hiraeth.

2. “Ma” (Japanese): Space

Existence as Space in Japanese Architecture

Ma (間) is not a void to be filled, but a living interval—the perceived pause between objects, the “space-time” that breathes life into form. In Japanese art and architecture, ma frames attention: a gap in a wall, a silent courtyard, the stillness before movement. This idea entered the global design discourse with Arata Isozaki’s landmark exhibition “Ma: Space-Time in Japan.” The exhibition showed that painting, theater, music, gardens, and architecture create a choreography of meaning through intervals rather than objects.

What matters is that ma is relational. This stems from how the elements face each other and measure each other: pillar to pillar, step to step, breath to breath. Traditional carpentry transforms this relationship into structure—the distance between columns (hashira-ma) becomes a fundamental unit of a house and is read as ken (bay). In this sense, “nothing” is actually a precise ratio that determines rhythm, appearance, and tranquility.

The Use of “Ma” in Modern Space Planning

Consider ma not as a metaphor, but as a design tool. Three practical steps:

- Design pauses. Intentionally incorporate “breathing” spaces into plans: courtyards in front of lobbies, niches along corridors, and small exterior sets that slow down arrival. These calibrated voids make wayfinding intuitive and provide moments for orientation and contemplation (light, view, bench, breeze). Contemporary discourse frames ma as a time-space-human relationship achieved through place-making; use this to organize urban thresholds and interiors in the same way.

- Do not reinforce the edges of the layers. Instead of a single thick wall, use adjustable layers (curtains, wings, sliding doors) to adjust privacy, airflow, and light throughout the day. This allows spaces to expand/contract over time, preserving the range not as a fixed boundary but as a variable element. Articles and exhibitions written on ma emphasize this temporal quality as much as spatial geometry.

- Program the space in between. Assign a purpose to the “now” spaces: a chair in a niche, a tea corner by the window, a shaded walkway that also allows for social interaction. When the intermediate space hosts a real activity, ma becomes public: people meet, spend time, and accept the rhythm of the building as their own. Research and theses on ma in contemporary contexts argue precisely this: that emptiness is the host of flows and encounters.

Lessons to be Learned from Traditional Japanese Design

In post-and-beam houses, the space between columns creates a repeating partition (ken) that organizes rooms, views, and movement. In Japanese applications, space was measured in tsubo (a square ken), while room layout was based on the tatami grid. This is proof that not only objects but also proportions and spacing structure life. Use consistent divisions to create a legible rhythm; leave a few divisions open (double height, courtyard) to allow the rhythm to breathe.

Engawa—a narrow veranda extending toward the garden—its edge becomes a livable space for sitting, greeting, and watching the rain. Today, you can interpret this as deep projections, porch-like galleries, and exterior corridors that soften the climate and invite chance encounters.

Tea rooms, Noh stages, and garden paths form the sequence of scenes: compress, release, turn, reveal. Borrow this dramaturgy for clinics, schools, and workplaces—short narrow passages before bright communal spaces, quiet entryways to reset your mood, framed views worth taking a few more steps for. The “Ma: Space-Time in Japan” exhibitions made this interdisciplinary logic visible; architects can put it to practical use.

3. “Gezelligheid” (Dutch): A Cosy Togetherness in Space

Creating Warmth in Shared Spaces

Gezelligheid is a Dutch cultural keyword meaning a shared warmth, sincerity, comfort, and easy camaraderie, and is etymologically derived from the word gezel (“friend”). It is not just an indoor atmosphere, but a social atmosphere that people actively create together. Linguist Bert Peeters defines the word gezellig as culturally rich and difficult to translate, showing how it expresses the places and moments where people want to be, want to do things together, and feel that “nothing bad can happen here.” This framework serves as a powerful design summary for hospitality and public indoor spaces.

A classic example is the Dutch bruin café (brown café): small rooms, worn wood, candlelight, and tables close together that encourage conversation with friends and strangers. The material palette and lighting—dark wood, tobacco-stained ceilings, soft, low-intensity lamps—deliberately create a social atmosphere, making conversation the “program.” Travel and culture guides consistently associate these cafés with a sense of gezelligheid.

Peeters also cites gezellige drukte—“pleasant bustle”—as a characteristic: enough people, low risks, and a relaxed rhythm. Design can stage this hustle and bustle through scale (small rooms), permeability (views facing the street), and rituals (coffee at 11 a.m., board games at the bar). In other words, gezelligheid is not a style, but a behavior enabled by the space.

Design Elements That Promote Social Comfort

Let’s start with three questions taken from Peeters’ definition of a gezellig space: Do people want to be here? Can they do simple things together? Does the room provide a sense of security and comfort? Translate these into concrete features: warm, dim lighting at eye level; tactile materials that soften sound (wood, fabric, cork); small tables placed close enough to hear each other; and edges that invite lingering—window-side chairs, bar counters, and seating near entrances.

Use the brown café as a design book: layered wooden surfaces, intimate corners, and informal seating areas instantly create social readability. Keep ceilings as modest as possible and allow lighting pools to create conversation “islands.” Avoid hard, echoing surfaces that inhibit conversation. These are not just aesthetic considerations, but environmental cues that are repeatedly mentioned when explaining why brown cafes feel so cozy.

Set the scene. Peeters shows that gezelligheid develops when people can do small things together for a while—have a drink, play a game, listen to a simple performance. Add gentle rituals to the calendar (acoustic nights, family-style dinners, neighborhood coffee hours). In signs and arrangements, prefer invitations over instructions; gezelligheid arises from consent, not control.

Urban Planning that Takes Sociability into Account

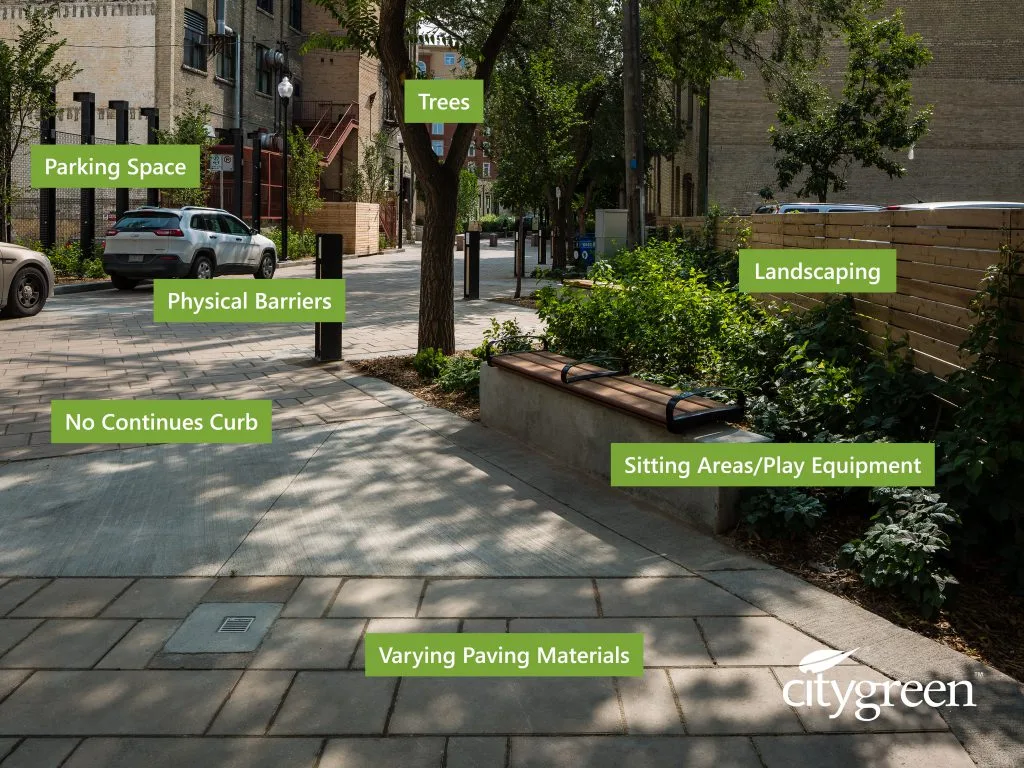

On an urban scale, the Dutch woonerf (“living street”) design adds sincerity to mobility. Emerging in the Netherlands in the 1960s and 70s, the woonerf treats the street as a shared social space: very low vehicle speeds, uninterrupted sidewalks, trees and benches along the roadway, and priority for pedestrians and play. Evaluations have shown that accidents have decreased, social interaction and children’s play have increased, and residents’ satisfaction is high; in other words, the street has become gezellig thanks to its design.

Historical hofjes (almshouse courtyards) offer another model: small houses surrounding a quiet green space, closed to traffic but open to communal living. Amsterdam’s Begijnhof demonstrates how this typology creates “urban oases” — semi-private areas of tranquility within the city where a sense of belonging is routinely practiced. Contemporary research and city guides document why hofjes have been attractive for centuries and how they still provide social comfort today.

Taken together, these examples align with Peeters’ semantic test for gezelligheid: environments that offer human presence, easy activities, and an inviting sense of security. Whether it’s a lively street, a courtyard complex, or a candlelit bar, design them on a small scale, with soft edges, and for daily rituals; the atmosphere will take care of the rest.

4. “Sobremesa” (Spanish): Those Left Behind After the Field

Design for Post-Function Moments

The word “sobremesa” refers to the time spent at the table after a meal: conversation, jokes, the quiet enjoyment that follows eating. Spanish language authorities define this word as “the time spent at the table after a meal,” which provides architects with a ready-made summary: design not only the meal, but also the moment that follows it.

Culturally, sobremesa is part of a broader Mediterranean ethic of friendship. UNESCO’s inclusion of the Mediterranean diet on its list explicitly celebrates hospitality, neighborly relations, and eating together not just as a menu, but as a shared cultural practice. Designing for sobremesa means honoring this social time and space that preserves conversation, eye contact, and a calm tempo.

Time usage data helps explain why these areas are important: Southern European countries (including Spain) spend more time eating and drinking than other countries, which naturally extends the “after” period. With this in mind, create arrangements that don’t require immediate conversion and micro-spaces near the table (a buffet for coffee, a corner seat for grandparents, a small play area for children) so that people can rearrange without leaving.

Architecture That Makes You Want to Stay

In indoor spaces, the tradition of “service environment” research shows that the physical environment (lighting, acoustics, temperature, seating arrangement) determines how long people will stay and how they will feel during their stay. Small decisions such as warm light pools at eye level, soft sound absorption, and comfortable, movable chairs extend the length of stay and facilitate conversation.

Cues in the environment are also important. Classic experiments on the tempo of background music have shown that slower tempos extend the time customers spend in the venue (and sometimes affect sales). You can translate this information into playlists that slow down the tempo of the venue after dessert. The goal is not consumption, but getting customers to agree to stay in the venue.

Evidence from public spaces outside the restaurant also points to the same conclusion. William H. Whyte’s fieldwork on public squares revealed that simple, movable chairs significantly increased dwell time and social interaction. This is because these chairs offer people choices: to move into the sun or shade, to join a small group, or to pull up a chair to listen to another story. This is the logic of sobremesa on a city scale.

The Cultural Value of Places That Don’t Rush

Sobremesa is socially important: it is where families come together, friends chat, and ideas emerge. Spanish media routinely presents it as a defining tradition, sometimes even suggesting it as cultural heritage, and Latin American writings reflect the same practice across the ocean. When architects design a room where people can “linger a bit,” they not only add comfort but also preserve a living social ritual.

At the urban scale, “third places” (cafes, libraries, parks) are valuable precisely because they provide a space for this relaxed togetherness. Contemporary interpretations highlight the need for these spaces to be revitalized and rebuilt as accessible, welcoming, and non-oppressive environments. Designing terraces, squares, and cafes that prioritize presence over efficiency reconnect cities to the pleasure of spending time in daily life.

Policy can either help or hinder. Cities like Barcelona actively regulate café terraces to strike a balance between neighbors’ comfort and street life; operators sometimes exert pressure in the opposite direction and impose time restrictions that shorten working hours. Good rules and good design aim for the middle ground: clear working hours and noise restrictions, but comfortable and flexible seating areas to allow the culture of lingering to continue.

5. “Heimat” (German): Sense of Belonging Through Place

Architecture and Identity

Heimat does not simply mean “home.” In German usage, it combines the concepts of place, memory, and belonging; it generally refers to the region or environment where a person has put down roots. This emotional weight is clearly evident even in dictionary entries: Heimat is the place where a person grew up or where they feel at home by living there continuously. For designers, this means that buildings can be more than just shelter; they can reinforce identity.

Historians show how Heimat shaped German identity by linking local and national elements. Celia Applegate argues that the “Heimat vision” emphasizes regional cultures rather than being a simple opposition to foreigners, while Alon Confino explains how Germans imagined the nation through local ties—transforming village landscapes, dialects, and traditions into national memory. For architects, this means designs that respect regional materials and patterns without caricaturing them.

This concept is powerful and flexible. Academics note that the concept’s ambiguity facilitates its use in marketing or politics, and that it can be inclusive or exclusive. This dilemma is part of modern German discourse (there was even a federal “Heimat” office in the interior ministry). Good design treats the Heimat concept not as an obstacle, but as an element that invites the creation of inclusive bonds.

Rebuilding Heimat in Post-Conflict Contexts

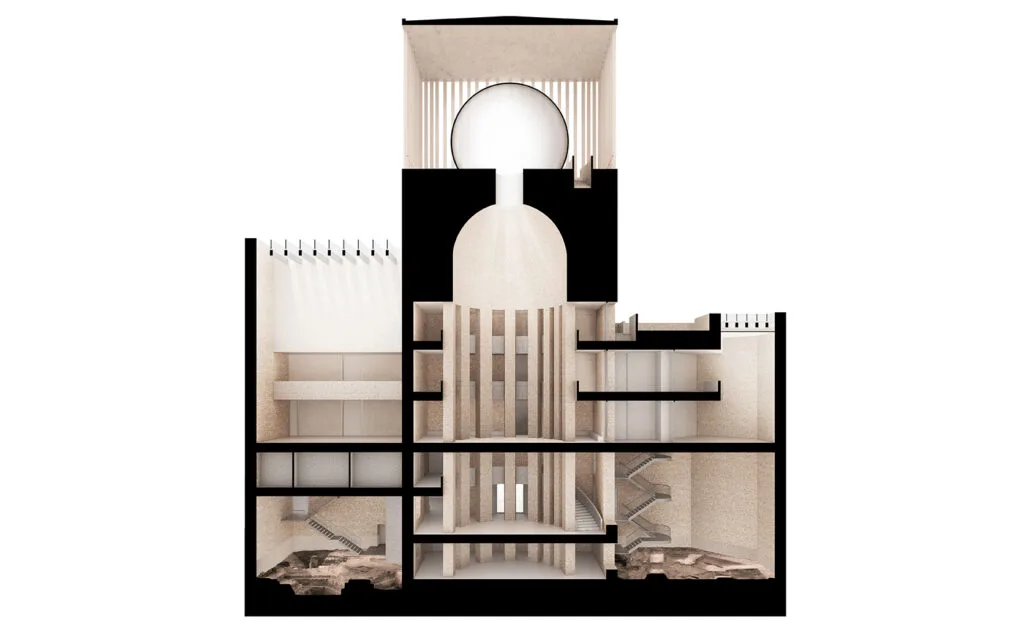

After the destruction, some places can help people return emotionally before they physically return. The Frauenkirche in Dresden is a striking example of this: largely rebuilt with donations (1994–2005), this church is seen by the church and the city as a symbol of reconciliation and European unity. Its structure blends new stones with the damaged originals, making memories visible rather than erasing them.

Germany’s decentralized culture of remembrance reinforces a sense of belonging in everyday life. Gunter Demnig’s project, Stolpersteine, marks the former homes of people persecuted by Nazism with small brass “stumbling stones” embedded in sidewalks. With over 116,000 stones in more than 1,800 municipalities, this network transforms streets into silent archives, enabling residents to hold memorial ceremonies at their doorsteps.

The Center for Documentation of Displacement, Exile, and Reconciliation in Berlin broadens its perspective from a single nation to a shared human experience. Opened in 2021, the center narrates the forced migrations of the 20th century and today, offering a public space to process losses and rebuild social trust. These are fundamental components of post-conflict Heimat.

Design for Multicultural Belonging

Contemporary Heimat must work for pluralistic cities. Architecturally, one answer is Berlin’s House of One: a synagogue, a church, and a mosque under one roof, connected by a central communal hall for encounter and learning. Designed by KUEHN MALVEZZI in collaboration with structural teams such as sbp and Arup, the project is located on the historic foundations of Petriplatz and links new coexistence to deep urban memory. This is an open spatial scenario for shared belonging.

Urban policy can support these spaces. Germany’s federal Soziale Stadt (“Social City”) program invested in neighborhood public spaces, community centers, and social infrastructure for twenty years; since 2020, it has been consolidated under the Sozialer Zusammenhalt (“Social Cohesion”) program. The goal is practical: to improve the everyday environments where people gather (libraries, courtyards, playgrounds), thereby enabling residents with different backgrounds to form lasting bonds. Architects can participate in these programs with modest, flexible designs created in collaboration with local communities.

6. “Duende” (Spanish): The Emotional Depth of a Place

Places That Invoke the Supreme Being

In Spanish, “Duende” can mean a mysterious, indescribable charm — an intensity that takes hold of a moment or a place.

Federico García Lorca took this term even further: not skill or style, but a dark, earthly power that makes art feel alive, a struggle that pierces through technique. When it comes to architecture, think of duende as a felt weight that carries us beyond words, created by the convergence of material, light, and silence.

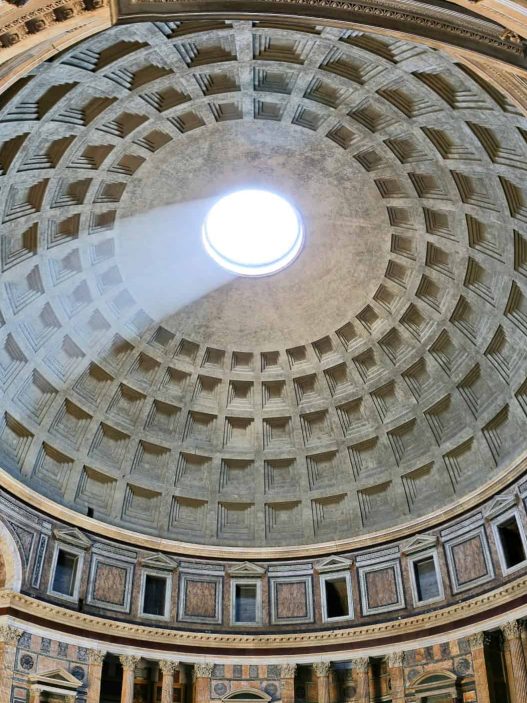

This approaches the limits of the sublime—feelings where attraction and unease intertwine, what philosophers like Kant called “pleasure through discomfort.” In spaces that compress and release light, heighten contrast, or confront death and memory, this vibration is felt.

Ronchamp’s pilgrimage chapel transforms a hill into a site of revelation by resisting beams of light with its thick walls. Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Field Chapel is a burnt wooden void clad in concrete, with a peephole at its center: raw, secluded, and strangely luminous. Ando’s Light Church consists of a cross of daylight cut into concrete—a sensitive simplicity that sharpens the senses.

Flamenco, the art form most closely associated with duende, is recognized by UNESCO for the diversity of emotions it conveys, such as sorrow, joy, fear, and delight, reminding architects that cultural rituals teach us how spaces can hold deep emotions.

Importance, Light, and Duende

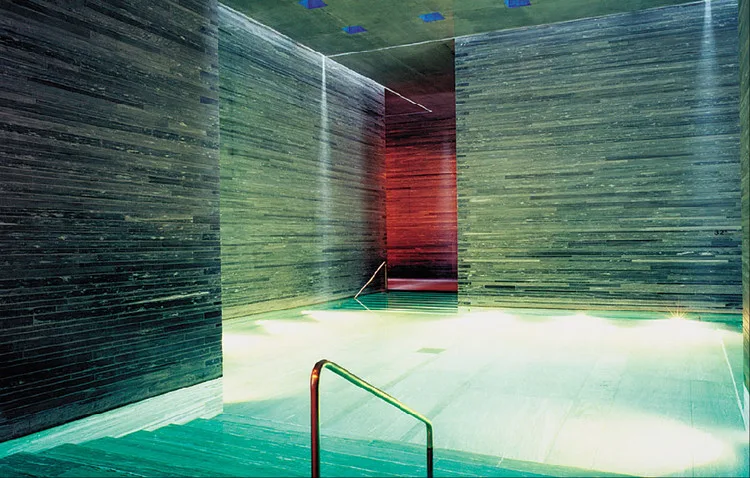

Peter Zumthor’s cornerstone is “atmosphere” — an intense, unique mood that makes a building’s presence felt. The authenticity of the material is part of this: In Vals, 60,000 local quartzite slabs, cool water, and dim light draw you into a stony silence; this is as much a sensory scenario as it is a plan. In Bruder Klaus, the interior is literally the memory of fire: 112 tree trunks emerging from concrete molds have burned, leaving a charred cave that directs light like a star.

Işık duyguları yazıyor. Ronchamp’ın açılı açıklıkları, duvar bir fenermişçesine ışınları dağıtır; Ando’nun beton kutusu, ışığın haçı karanlığı kesip biçtiğinde bir şapel haline gelir. Çağdaş araştırmalar bu sezgiyi destekliyor: “atmosfer”, ışık, doku, geometri, akustik ve düzenin ruh halini ve davranışları nasıl uyumlaştırdığından ortaya çıkar — bu, tasarlayabileceğimiz ve giderek daha fazla ölçebileceğimiz bir etkidir.

Environmental psychology offers a threefold concept to explain why some places are appealing and others are boring: enchantment, consistency, and authenticity. Duende is not the same as these concepts, but it draws on their interaction: when consistency is very low, grandeur turns into chaos; when enchantment is very low, intensity is lost.

Architecture as Emotional Performance

Lorca’s duende is born in the living struggle; in buildings, “performance” is the sequence we choreograph over time for bodies. Approaches that constrict and then open, thresholds that silence noise, and rooms that allow light to enter like a signal—this is the staging. Ando’s side entrance and angled screen in Ibaraki transform a simple box into a dramatic emergence; when you first see the bright cross, it is not a static image, but an entrance line.

If duende seems like a non-scientific concept, pay attention to the growing evidence: Research shows that built form can alter emotions, physiology, and behavior; dimensions such as enchantment and coherence consistently shape aesthetic response in both natural and architectural settings. New projects are testing atmospheres using neural, physiological, and self-reporting measurements, treating mood as a design variable rather than a chance occurrence.

So let design be like a performance: write the rhythm (light and shadow), choose the actors (stone, water, wood, air), and score the silences. When structure, sequence, and perception are in harmony, spaces can carry duende—a depth you don’t just see, but feel in your bones.

7. “Wabi-Sabi” (Japanese): The Beauty in Impermanence

Celebrating Aging, Wearing Out, and Time

Wabi-sabi is a Japanese aesthetic that finds beauty in imperfection, transience, and incompleteness. “Wabi” refers to humble simplicity, while “sabi” expresses the quiet patina of age—the softening, scratches, and wear that time brings. These two concepts together encourage designers to accept knots in wood, fine cracks, and sun-faded pigments not as flaws to be removed, but as part of the space’s authenticity.

Scientists base the meaning of the word sabi on meanings such as “rustic patina” and “well-aged”; this represents a shift from its earlier meaning of desolation towards a positive appreciation of the traces of time.

In practice, this means paying attention to details for an elegant transformation: allowing copper or weather-resistant steel to form self-closing oxide layers; selecting surfaces that can weather evenly; highlighting repairs rather than hiding them. For example, weather-resistant steel is designed to develop a protective surface “rust” that stabilizes and reduces future corrosion—this is the engineering reflection of sabi‘s patina. This layer heals itself even after scratches.

Designers can also draw inspiration from kintsugi, the art of repairing broken pottery with lacquer and gold. This is a material metaphor for repair interpreted as renewal rather than loss. Institutions explaining kintsugi explicitly relate it to wabi-sabi’s embrace of imperfections and time.

Wabi-Sabi as a Sustainable Aesthetic

Wabi-sabi is naturally compatible with circular design: preserve what already exists, design for repair, and allow materials to age gracefully. Circular economy frameworks emphasize eliminating waste, circulating products at their highest value, and regenerating nature. Architects can express these principles through durable finishes, adaptable plans, and repair-friendly details.

Examples of Japan’s culture of repair include boro textiles—layered, repeatedly patched garments—used for generations and now studied and exhibited as a creative craft. Seeing the patch not as a compromise but as an aesthetic expression is the essence of wabi-sabi.

At the urban scale, wabi-sabi’s respect for time supports adaptable reuse rather than demolition. AIA’s professional guidance encourages design for adaptability, demolition, and building/material reuse. These choices preserve embodied carbon and keep the “story” of places legible even as they evolve.

Architectural Examples of Imperfect Beauty

Approximately every 20 years, Japan’s most revered Shinto shrine is completely rebuilt in a ceremony called Shikinen Sengū. This practice renews the wood, passes on craftsmanship, and balances permanence with impermanence — a living monument to the wabi-sabi philosophy on a landscape scale.

Katsura’s strolling garden and tea pavilions embody the ideal of a tea house with natural materials, elegant simplicity, and rooms open to seasonal changes. The sukiya-zukuri tradition represented by this structure emphasizes rustic harmony, wood left in its natural state, and an intimate scale rather than monumentality.

Kyoto’s famous dry garden — fifteen stones placed on raked gravel — invites the eye to rest on the absence as much as the form. You cannot see all the stones at once; the absence is designed. This is a spatial lesson in acceptance and mindful perception.

Contemporary designers use charred cedar (yakisugi) cladding that is resistant to decay and insects while creating a stylish surface, or honest patina metals that allow buildings to visibly age over decades, recording the climate and touch without hiding behind plastic perfection.

Discover more from Dök Architecture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.