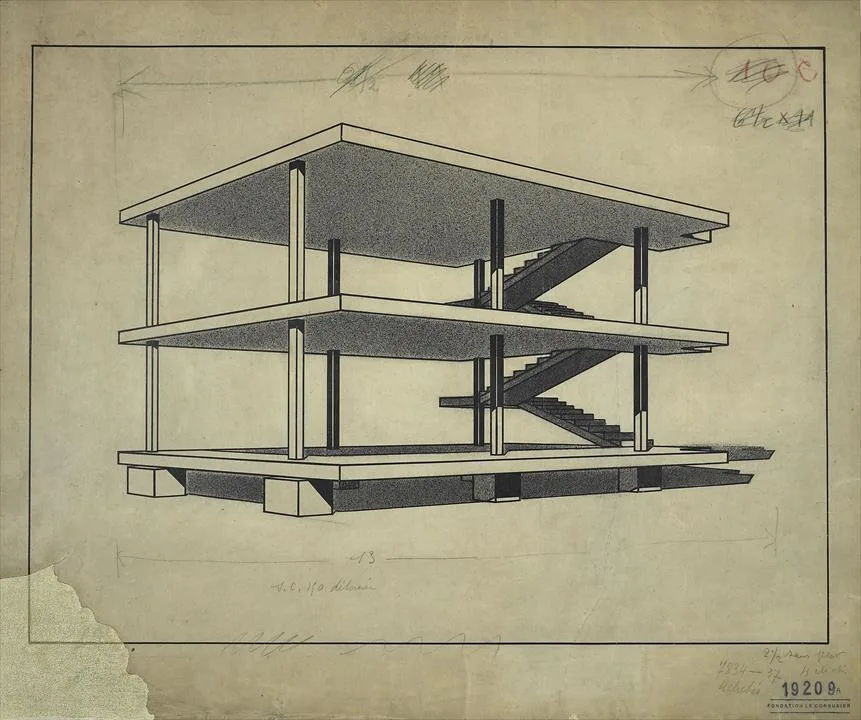

By the early 20th century, the Industrial Revolution had transformed society’s relationship with technology and mass production. Le Corbusier embraced this “machine age” ethos: he rejected historical embellishment and advocated efficiency and standardisation. He had learnt the virtues of reinforced concrete construction and mass production alongside Auguste Perret and Peter Behrens. In 1915 he sketched the Dom-Ino house, a modular reinforced concrete slab on pilotis (thin columns) without load-bearing walls, which he explicitly designed for prefabricated, mass-produced housing. In 1918, together with the artist Ozenfant, he formulated Purism, a doctrine to “refine and simplify design, abandon ornamentation” and make architecture “as efficient as a factory assembly line”.

He even named a proto-urban project Maison Citrohan to signify that housing should be built like Citroën cars, adopting the methods of the automotive industry. In his 1923 manifesto Vers une Architecture, Corbusier stated that “A house… is a machine for living in”. This slogan summarised his belief that a modern house should be rational, standardised and functional, like a well-designed product, and reflected a wider modernist turn away from decoration towards function and industrial logic.

Transport technology was a lively source of inspiration. Corbusier was obsessed with the automobile: He owned a Voisin C-7 Lumineuse from 1925 and often posed in front of his buildings as a symbol of modernity. He praised automobiles as “beacons of the future of architecture” and even drew a low-cost “Voiture Minimum ” (a simple automobile that incorporates aerodynamics and functionality) to test automotive minimalism. Likewise, ocean liners deeply influenced him. He admired their sleek white hulls and efficient layouts; the S.S. Normandie in particular convinced him that a building could be both functional and beautiful.

He wrote that “ocean liners… demonstrate the potential of high-service megastructures to provide ideal living conditions”. He borrowed nautical motifs in his architecture – for example, the living room of the Villa Savoye was deliberately designed like an upper deck cabin, complete with a tubular balustrade and curved promenade deck. In general, Corbusier equated architecture with the engineering marvels of his time – aeroplanes, grain silos, ships and cars: “the religion of beautiful materials” was dying, and modernists like him replaced it with pure function, proportion and images of machinery and transport.

Classical Ideals and the Five Points: A New Domestic Space

Although Corbusier rejected past styles, he utilised classical concepts (Vitruvius’ solidity, utility and taste) but redefined them with modern technology. He believed that structural order and proportion (firmitas) were necessary, but that functional utility (utilitas) and aesthetic pleasure (venustas) no longer required ornamentation. As he wrote in L’Art décoratif d’aujourd’hui (1925), the ornamental fad was a “quasi-orgy” in its death throes, to be replaced by “useful, well-designed” objects whose elegance came from their perfect function. In practice, this meant translating classical ideas into five technical principles – the famous Five Points of the New Architecture (1926-27) – and applying them to houses, turning them into “machines” for living.

Villa Savoye (Poissy, 1928-31) epitomises these principles. It is raised on slender pilotis (columns) so that the living volume floats above the garden and its main façade is free of structure. A long strip of windows runs along the façade, providing equal daylight to all rooms, and the roof is flat and planted as a garden terrace. Together these features realise Corbusier’s Five Points:

- Pilotis (slender columns ) raises the building (solidity) and frees the ground plane for circulation and light.

- Free floor plan: With the structure on columns, the internal walls are not load-bearing and can be positioned arbitrarily (beneficial).

- Free facade: The outer wall becomes a weightless screen and allows for creative facade design (and large glazing).

- Horizontal windows (ribbon windows): Continuous glazed bands fill the interior with light (utilisation and pleasure).

- Roof garden: A flat roof provides an outdoor recreation area and replaces the disappearing footprint of the house with greenery (pleasure and return of nature).

These innovations demolished the old compartmentalised house. The interior was reorientated as a continuous, open flow: instead of hierarchical rooms, families moved through a series of interconnected spaces. Corbusier described this experience as an “architectural stroll”, in which one walks through the house to fully appreciate it. In Villa Savoye, for example, a ramp leads from the living areas to the roof, where the inside and outside blend into each other. Corbusier boasted that in such buildings “the plan is pure… made precisely for the needs of the house… It is poetry and lyricism supported by technique”, he boasted. In short, the Five Points mechanically secured solidity and light, while the absence of ornamentation allowed function and proportion to be the “taste” of architecture.

Modernist Utopias: Housing Reform, Urban Planning and Reality

Le Corbusier’s analogy of the “machine” extended to social reform and urban planning, which he saw as part of the same project. He believed that standardisation on an industrial scale could solve housing shortages and public health crises. In the 1920s, he proposed zoned, tower-filled cities dominated by sunlight, fresh air and productivity. His Plan Voisin (1925) for Paris, for example, envisaged bulldozing large swathes of dense, sickly apartment buildings (then ravaged by tuberculosis) and replacing them with 18 sixty-storey cruciform skyscrapers set in a linear park. Each tower would contain both homes and offices, cars would travel on underground roads, and extensive green belts would provide light and ventilation. This radical zoning, directly influenced by CIAM’s Charter of Athens ideals, treated the city as a machine with separate functions.

Plan Voisin would raze Paris’ historic Seine and medieval street grid to make way for this vision of the “Ville Radieuse”. Corbusier argued that this plan would eliminate unhealthy overcrowding, but critics warned that it would also “erase centuries of architectural and cultural history” and impose a cold, monotonous logic inappropriate to the human scale of Paris. The harsh reaction to Plan Voisin foreshadowed later controversies: how top-down modernism clashed with organic urban life.

In the field of housing, Corbusier’s utopian ideals were partially realised after the Second World War. The Unité d’Habitation inMarseille (1952) is a concrete megastructure of 337 apartments topped by communal facilities and connected by internal “streets”. It was literally a living machine: rising above the pilotis and surrounded by parkland, it included shops, a hotel, a day care centre and a rooftop pool and jogging track.

Corbusier based the layout on a ship, reflecting his ship-inspired logic (“if it looks a bit like a cruise liner, it is no coincidence”). Contemporary critics hailed it as a breakthrough – architectural historian J.M. Richards praised the Unité for “placing clean and healthy housing on a parkland” and noted how it fulfilled the modernists’ promise of hygienic, sunlit living.

However, the social vision of the machine metaphor has also fallen short in many applications. Utopian high-rise buildings often created alienation and management problems. The famous Pruitt-Igoe public housing estate in St. Louis (1951-72), clearly influenced by Corbusian/CIAM planning, collapsed due to crime and decay; its demolition in 1972 was declared “the death of Modern architecture”. Critics such as Reyner Banham have noted that the strict Athens Charter zoning “killed research into other areas of urban housing”.

In practice, Le Corbusier’s grand plans sometimes neglected how people actually used space and city life. Even Unité, while structurally ingenious, was built so far from urban centres that its “avenues in the sky” often felt disconnected from real communities.

Corbusier’s machine analogy embodied early modernism’s belief in technology, standardised design and social engineering. It reshaped architecture – reinforced concrete structures, flat roofs, open plans and communal housing blocks.

But it also revealed a dilemma: the pursuit of pure efficiency and abstraction could clash with cultural tradition and life on a human scale. His legacy, from Villa Savoye to Unité and beyond, illustrates both the innovations of 20th-century modernism and the tensions inherent in treating buildings and cities rigidly as machines.