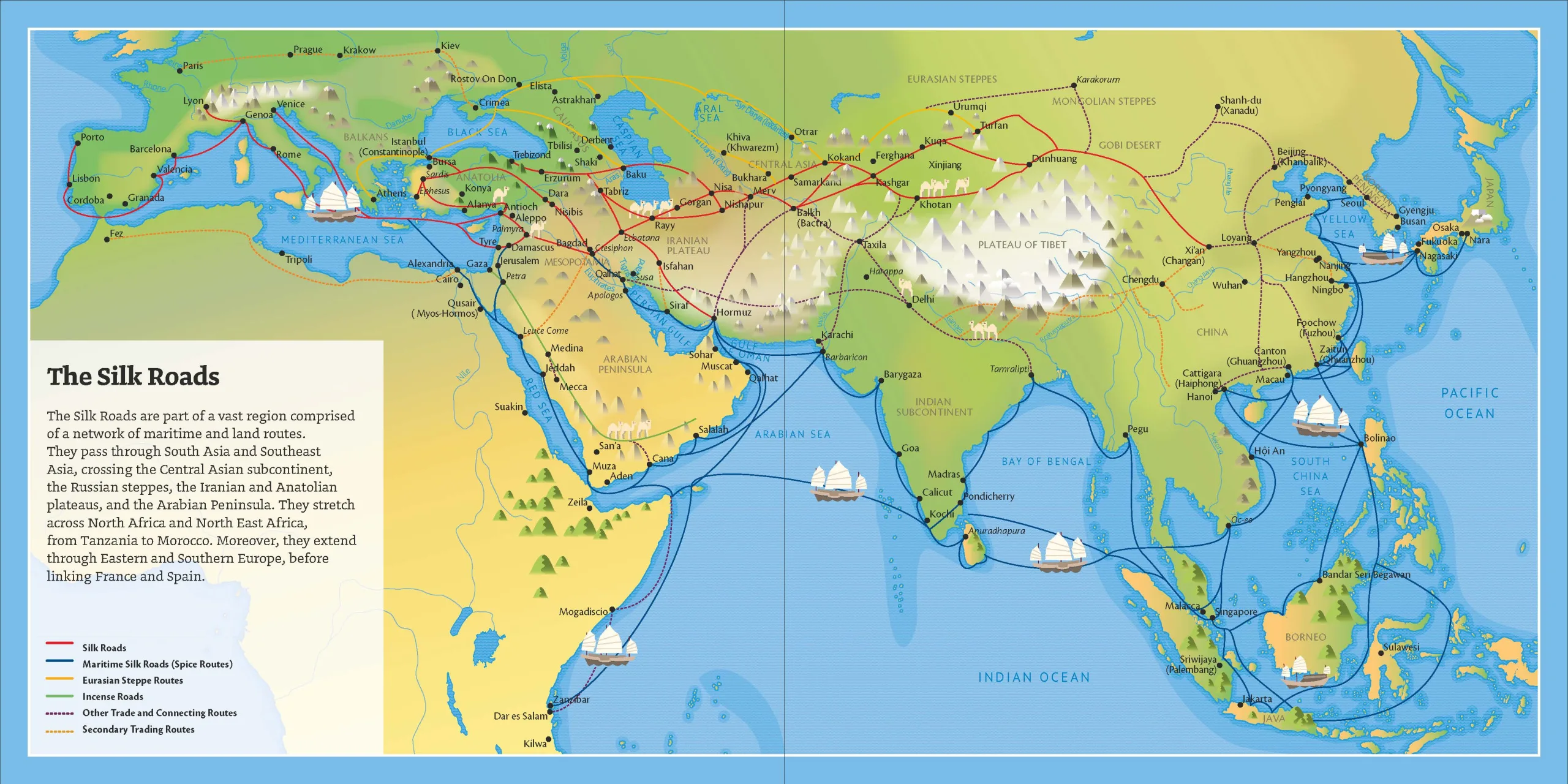

Trade routes build cities. For over a thousand years, the Silk Roads—a network of corridors connecting East and West—transformed architecture into a language of exchange. Caravanserais offered enhanced hospitality; bazaars combined storage with an opulent atmosphere; mosques, madrasas, and mausoleums gave public meaning to wealth. In 2023, UNESCO added the Zarafshan-Karakum Corridor, an artery passing through Samarkand, to its list to fully recognize the power of routes, nodes, and intercultural craftsmanship to shape cities.

Think of the Silk Roads not as a single route but as networks: ideas, pigments, bricks, calligraphy styles, and structural techniques traveled alongside saffron, paper, and porcelain. The cities along these corridors display layered “commercial architectures”: squares tailored for markets, gate towers scaled for caravans, and religious complexes that also served as conference halls and lodging. Our first stop, Samarkand, represents the pinnacle of this phenomenon, where transit transformed into a monumental urban form under the patronage of the Timurid dynasty.

Beyond the monuments, the fabric of daily life—courtyard houses, neighborhoods, and street markets—reveals how commerce has become woven into the fabric of life. In the old city of Samarkand, narrow streets and inward-facing houses connect social and economic worlds, while the bazaar streets carry out the city’s public activities such as shopping, bargaining, praying, and resting. This mix of magnificent complexes and finely crafted local architecture is the distinctive feature of the architecture created by the streets.

Samarkand: Crossroads of Cultures

The silhouette of Samarkand—domes, pishtaqs, and minarets covered in blue—symbolizes the Timurid period when the city became the cultural capital of Central Asia. The complexes most frequently mentioned by visitors — Registan, Bibi-Khanym, Shah-i Zinda, Gur-e Amir, and Ulugh Beg’s Observatory — form the basis of an urban narrative where science, ritual, and trade shared the same stage.

However, the city’s identity is not solely monumental. The historic center is organized into neighborhoods: a dense network of courtyard houses, workshops, and small mosques. These neighborhoods, with rooms surrounding shaded courtyards, reflect centuries-old ways of life and local craft economies—architecture scaled to families, guilds, and seasons.

Samarkand’s status as a “crossroads” is both geographical and practical: an oasis where roads intersect on the Zarafshan River and a place where materials, techniques, and scholars converged—from cobalt for tiles to the astronomers around Ulugh Beg. The result is a city that reads like a dictionary of Silk Road urbanism.

The Timurid Legacy and Monumentality

Timurid architects transformed magnificent structures into urban order. The three madrasas at Registan—Ulugh Beg (1417–20), Sher-Dor (17th century), and Tilla-Kari (17th century)—surround a carefully designed square where teaching, ceremonies, and trade were conducted together. Their soaring portals and muqarnas cornices defined the “Timurid look”: massive entrance arches, double-shelled domes, and surfaces woven with geometry and calligraphy.

The Bibi-Khanym Mosque, built after Timur’s campaign in India, pushed the boundaries of scale—a community complex proclaiming imperial ambition with its wide doors and marble details. Its decoration combines multiple tile systems: mosaic tiles (hand-cut pieces assembled like a mosaic), bannāʾī (glazed interlocking patterned bricks), and cuerda seca (color fields separated by resist lines). Even after partial collapses and modern restorations, it continues to symbolize the city’s monumental ambition.

Timurid monumentalism also encompassed science. Ulugh Beg’s observatory—an architecturally integrated instrument—was embedded into the hilltop to eliminate vibration and housed a fixed meridian sextant with a radius of approximately 40 meters. The star catalog Zij-i Sultani produced here set a benchmark for astronomical accuracy centuries before telescopes. Here, architecture was not the backdrop for knowledge; it was the measuring instrument.

Urban Fabrics and Caravanserai Networks

Under the domes, daily life unfolded in neighborhoods: compact blocks of inward-facing houses with shared walls, arranged around courtyards. Rooms were used flexibly according to the time of day; streets balanced climate and privacy; small squares and neighborhood mosques formed the center of social life. This structure, still legible today, explains how a city that was the capital of empires could also function as a city of neighbors.

Markets connected these neighborhoods to the monumental center. The historic bazaar near Bibi-Khanym and the long-standing Siab market demonstrate the continuity of trade streets as the urban backbone, featuring storage cells, stalls, and places of worship. In Silk Road cities, such markets were typically connected to caravanserais (courtyard-enclosed inns), allowing merchants to house their horses, sleep, and conduct trade within a day’s walk of the main square.

Samarkand was located within a corridor densely populated with these key junctions. Along the Zarafshan-Karakum route—now recognized by UNESCO as a series of sites—caravanserais such as Rabati Malik (between Samarkand and Bukhara), water reservoirs (sardobas), and fortified courtyards adorned the desert. When read together, the mahalla, bazaar, and caravanserai form a single system: local life, urban trade, and long-distance trade are intertwined with urban design.

Color, Craftsmanship, and Material Identity

The surfaces of Samarkand are like a craft curriculum. Timurid architects combined various techniques to harmonize light and patterns: mosaic tiles for sharp-edged geometric patterns; bannāʾī for drawing patterns on brick and tile; and cuerda seca for drawing multicolored motifs without the colors blending. The decoration of Bibi-Khanym exemplifies this mix of techniques, combining structural boldness with surface ingenuity.

The city’s blue hues—cobalt, turquoise, and white—have deeper roots. In the century before Timur, lajvardina (a dark cobalt glaze overlaid with enamel and gold) was used on tiles in the Shah-i Zinda necropolis, and this taste carried over into the Timurid period. The result is the famous “Samarkand blue”: domes and portals that reflect the desert light during the day and hold it at dusk.

Craftsmanship was (and still is) the social infrastructure. Workshops tied to neighborhoods sustained wood carving, brick making, tile cutting, and painted ceilings; intangible traditions like music, miniature painting, and embroidery also nourished the same aesthetic world. This ecosystem of skills made large-scale architecture possible and provided a living foundation for today’s conservation efforts.

Xi’an: East Gate

Xi’an is located at the eastern end of the Silk Roads, where caravans once set out for Central Asia. This role is officially recognized in UNESCO’s “Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor Route Network.” This network is a 5,000-kilometer strip stretching from Chang’an (the Tang dynasty capital located in the present-day Xi’an area) through western China to Central Asia. This list highlights the elements that make the city unique: long-distance trade, religious interaction, and the spread of technology and ideas.

City Walls and Grid-Pattern City Planning

Enhanced defensive urban planning.

Xi’an’s existing walls—largely rebuilt during the Ming dynasty—enclose the historic center in an almost rectangular area with a perimeter of approximately 13.7–13.75 km. The average height is ~12 m, with the top section 12–14 m wide and the base 15–18 m wide. Every ~120 m, there are protruding walls for firing from the sides. Beyond its military past, the walls now serve as a public space—accessible by bicycle and on foot, legible from above—transforming the defensive infrastructure into an everyday urban area.

A city drawn like a board game.

Beneath today’s street grid lies the Tang-era plan of Chang’an: nine main north-south and twelve east-west avenues dividing the capital into 110 walled rectangles — 108 residential/official districts and two state-run markets. The district gates closed every night, enforcing a curfew and daily rhythm of movement. This plan combined imperial symbolism with clear logistics for crowd management and the flow of goods and people.

The legacy of walls and grids offers two working ideas for 21st-century cities:

- Reuse of ancient walls as green mobility loops (Xi’an’s wall-top promenade, as an “entertainment infrastructure” model)

- Neighborhood-scale planning — walkable superblocks with strong edges and clear entrances — has been reinterpreted with open boundaries, mixed uses, and public transportation.

Research on Chang’an’s neighborhoods demonstrates how the size and content of blocks shape daily life. This information is useful for setting contemporary block lengths, service passages, and corner programs.

Chang’an and the Influence of Buddhist Architecture

The Giant Wild Goose Pagoda (Dayan Ta) at the Daci’en Temple was first built in 652 to house the sacred books and paintings brought back from India by the monk-scholar Xuanzang. It became both a spiritual symbol and an architectural lesson: a square, stepped brick tower with protruding “eaves” that mimic the wooden structure, transforming the Indian stupa into part of the Chinese city skyline. This site is now part of the Silk Roads World Heritage community.

On the other side of the city, the Small Wild Goose Pagoda (684 CE) at Jianfu Temple offers a more compact example of Tang architecture. Together, the “Great” and “Small” pagodas demonstrate how Buddhism took root in Chang’an through its translation centers, monasteries, and visible markers within the urban fabric. These structures served as elements that anchored processions, teachings, and pilgrimages in a capital organized for administration and trade.

The pagodas here are not just monuments, but also programmatic tools: archives, markers, and wayfinding devices. Brick-simulated wooden syntax also offers a broader lesson for contemporary applications: how we can “translate” foreign forms into local craft and climate without losing their meaning. (Britannica’s explanation of Dayan Ta’s simulated wooden details continues to provide a clear starting point on this subject.)

Markets, Mosques, and Cultural Fusion

During the Tang Dynasty, Chang’an centralized trade in the Eastern and Western Markets. These markets were state-controlled areas that housed warehouses, currency exchange offices, and artisans. Their location within the grid plan made long-distance trade understandable and controllable. This was an urban strategy that formed the basis of the capital’s cosmopolitan economy.

A mosque that looks like a temple but faces Mecca.

The Great Mosque of Xi’an (Huajuexiang) embodies the hybrid nature of the Silk Road. Arranged as a series of courtyards and pavilions in a long, narrow space, the mosque resembles a Chinese temple in its layout and roofline, yet its axis extends east-west, aligning the prayer hall with Mecca. Blue-glazed tiles, calligraphy, and garden courtyards combine Islamic devotion with Chinese craftsmanship.

The same blend is reflected in today’s Muslim Quarter, where halal kitchens, spice vendors, and bakeries form a vibrant market culture tied to the city’s Silk Road origins. For urban planners, this lesson is practical: when boundaries are permeable, roads are open, and small shops support daily rituals and transactions, religious and commercial life can share the public space.

Bukhara: Sacred Geometry and Public Space

Bukhara is located on the Silk Roads as one of Central Asia’s best-preserved medieval cities. Its urban fabric, consisting of mosques, madrasas, caravanserais, and neighborhoods, is still legible at the street level. UNESCO recognizes the historic center for this continuity, where sacred spaces and civic life intertwine around courtyards, squares, and commercial streets.

The “sacred geometry” here is not a metaphor: from the interlocking brick patterns of the perfectly cubic Samanid Mausoleum to the calibrated proportions of the Po-i-Kalyan complex, Bukhara’s patterns and measurements take on a public meaning. The Samanid Mausoleum (10th century) displays sophisticated brickwork and rhythmic voids; centuries later, the Kalyan Minaret anchors a city-wide axis that organizes the mosque, madrasa, and square.

Madrasas and Courtyard Typologies

The Mir-i-Arab Madrasa (1530s) faces the Kalyan Mosque across a shared courtyard. Both utilize the classical four-iwan plan: axial vaulted halls opening onto a central courtyard and surrounding student cells (hujras). This layout balances the ritual axis with daily life (lessons, prayer, and rest) within a single climate-controlled enclosed space. Mir-i-Arab has functioned as a religious school from the Shaybanid period to the present day, highlighting the durability of this typology.

Deep arched passageways, two-story galleries, and tree-shaded courtyards mitigate Bukhara’s dry heat while structuring social time—shade for studying during the day, open sky for fresh air at night. At Po-i-Kalyan, the madrasa-mosque duo, the minaret as a vertical symbol, and the square as a public “living room” read like a courtyard campus. The complex’s form—minaret, mosque courtyard, madrasa courtyard—demonstrates how sacred geometry regulates both movement and microclimate.

The same logic (clear axes, framed courtyards, thick edges) scales up to structure the neighborhoods and squares of Bukhara, uniting education, worship, and commerce into a single walkable network. Today’s designers still draw on these lessons: perimeter rooms for thermal mass, layered thresholds for privacy, and courtyards as adaptable social intensifiers.

Water Infrastructure and Urban Cooling

Before modern pipes were invented, Bukhara organized its streets and squares around hauz—stone-lined pools fed by canals—creating evaporative cooling, water access, and shaded meeting places. Lyab-i-Hauz (“by the pool”) remains the best-known example. This complex forms a whole where the pond, madrasa, and hankah mutually support each other in terms of climate, worship, and trade.

Stagnant water brought disease with it; during the Soviet period (1920s-30s), most city pools were filled in. Lyab-i-Hauz survived and became a social anchor point once again. Historically, its water was supplied by the Shahrud canal through closed channels (aryks). The microclimate of the square—shade, breezes over the water, and nighttime radiation cooling from the hard edges—demonstrates how simple hydrology can shape urban comfort.

The reintroduction of small water bodies, shaded seating areas, and narrow canal banks can cool hot cities with minimal energy. Bukhara’s hauz system serves as an example for contemporary “blue-green” squares that combine social life with passive climate control.

The Role of the Marketplace in Urban Form

Dome-shaped intersections (toki) as traffic concentrators.

Bukhara’s trade domes—Toki Zargaron (jewelers), Toki Telpak-Furushon (hat sellers), and Toki Sarrafon (money changers)—are located at important street intersections. Thick stone walls cool the air and turn street intersections (chorsu) into urban “rooms” where people, goods, and information are exchanged. The largest and best preserved, Zargaron, is located at the intersection of the city’s east-west and north-south axes.

The linear backbone of covered markets.

Between the Toki, long vaulted arcades (tims) form a shaded trade corridor; the most important is Tim Abdullah Khan (1577), which connects religious complexes with trade streets. This chain of enclosed spaces demonstrates how Bukhara’s economy and movement were integrated into a single continuous microclimatic system.

Istanbul: Between Continents and Empires

Adaptable Reuse Over the Centuries

Layers of faith, layers of stone. Few cities showcase reuse like Istanbul. Hagia Sophia alone tells a 1,500-year-old story: Byzantine cathedral (6th century), Ottoman imperial mosque (post-1453), museum during the Republican era, and since 2020, once again a mosque, while remaining one of the most important monuments on UNESCO’s “Historic Areas of Istanbul” list. The nearby Chora (Kariye) complex has undergone a similar process and reopened as a mosque in May 2024 following restoration. These transformations demonstrate how the buildings have survived by adapting their uses while preserving their world heritage value.

From Byzantine churches to Ottoman mosques, modern museums, and back again. Istanbul’s fabric is full of transformations: the Zeyrek Mosque complex (formerly the Pantokrator Monastery) forms part of a UNESCO site, while the Arab Mosque was built in the 14th century as a Genoese Dominican church, and its Gothic architecture is still clearly visible beneath its minaret. Across the Golden Horn, an old customs warehouse has been transformed into the new Istanbul Modern museum (Renzo Piano, 2023), showcasing contemporary reuse and cultural programming on the historic waterfront.

Adaptive reuse in Istanbul is not only symbolic but also a technical issue. Restoration campaigns, legal status changes, and urban management plans mediate between dedication, tourism, and conservation. UNESCO’s monitoring of Hagia Sophia and Chora after the status changes highlights the balance between “living” monuments and global heritage expectations.

The Mosque as an Urban Anchor

Ottoman imperial mosques were typically constructed as multi-building complexes (külliye) donated by charitable foundations. In addition to prayer halls, they housed schools, kitchens, bathhouses, clinics, libraries, fountains, and markets, thereby providing social services and regular pedestrian traffic to neighborhoods. The Süleymaniye complex (1550-57), built by Sinan, is a classic example of this, bringing together madrasas, a hospital, a nursing home, kitchens, bathhouses, and the tombs of Süleyman and Hürrem Sultan in a single urban acropolis.

A form that shapes a silhouette and a neighborhood. Architecturally, the Ottoman domes and half-domes frame the inner courtyards and streets, while slender minarets serve as beacons in the urban landscape; this whole organizes the movement, markets, and daily rhythms around it. In Istanbul, this reaches its classical expression in Sinan’s Süleymaniye Mosque. The mosque’s central dome and layered volumes define the skyline as a means of orientation, both spiritual and urban.

Mosque economies: bazaars as donations. Many complexes covered their maintenance costs through adjacent income-generating buildings. For example, the Egyptian Bazaar was built as part of the New Mosque complex, and shops were rented to support the mosque’s activities. This was an urban model linking commerce with civil and religious life.

Trade Ports and Architectural Hybridization

Ports at the heart of cultural mixing. On the northern shore of the Golden Horn, the Genoese Pera/Galata grew as a colony surrounded by walls with its own tower and streets. The Galata Tower (1348) and the remains of the walls recall this maritime outpost where Latin, Greek, Jewish, and later Ottoman communities exchanged goods and architectural ideas, forming the basis for centuries of hybrid forms.

Traveling typologies: from the han to the passage, then to the bank. Istanbul’s commercial center combined the Ottoman “han” (caravanserai-warehouse) concept with European passages and 19th-century financial palaces. Bankalar Caddesi in Karaköy housed the financial district of the late Ottoman Empire, including the headquarters of the Ottoman Imperial Bank (now SALT Galata). Designed by Alexandre Vallaury, this building reflected an imported Beaux-Arts language adapted to the Levantine port street.

The 21st-century waterfront laboratory. Today’s Galataport has redesigned the same waterfront strip with a world-first underground cruise terminal, connected by a cover system that creates a temporary customs zone when ships dock, thus opening the promenade for public use the rest of the time. The new Istanbul Modern next to it deepens the mix of culture and commerce while keeping the port legible as a public space. A contemporary hybrid that still listens to the port’s long memory.

Kashgar: Local Resilience and Spatial Memory

Soil Architecture and Seismic Compatibility

Traditional Uyghur houses in Kashgar are constructed using earthen techniques such as adobe bricks and compacted earth, and are typically combined with wooden elements. Earthen walls provide thermal mass and can be quickly repaired using local soil; wooden elements (ring beams, ties, straps) help the fragile earthen structure behave more like a system. Conservation research on earthen buildings recommends precisely this type of hybrid structure: continuous timber/tie beams, vertical and horizontal ties (bamboo or steel wire), corner keys, and lightweight diaphragms — interventions proven in shaking table tests and field restorations.

Kashgar is located near the active fold and thrust belt on the edge of the Tarim Basin. The devastating earthquakes that occurred in 2003 (approximately 100 km east of Kashgar, in Bachu/Jiashi) resulted in the deaths of more than 250 people and the destruction of tens of thousands of adobe houses. This hazard profile explains why safety is a recurring topic in discussions about the city’s redevelopment and why low-tech reinforcement is important for the survival of existing structures. The applicable kit for designers renovating earthen houses is clear: add a continuous ring beam at the eave level; connect parallel walls with ties; secure wall-roof connections with straps; and, where acceptable, transition to limited wall corners or partial frames.

Use locally sourced timber/bamboo for bands and ties, keep diaphragms lightweight to reduce inertial loads, and prioritize redundancy at openings and corners. These measures have repeatedly improved the life safety performance of adobe structures worldwide without compromising local character. This approach is highly suitable for Kashgar’s material culture.

Courtyards as Thermal and Social Regulators

In Kashgar’s hot and dry climate, inward-facing houses with shaded courtyards balance extreme temperatures: high-mass walls absorb heat during the day and release it at night; narrow openings and courtyards filled with plants support stack and cross ventilation. Research on Chinese courtyard types and arid region courtyards shows that daytime shading + nighttime openings can significantly reduce working temperatures — a finding consistent with the daily rhythms of Uyghur homes.

Recent simulations using Kashgar housing geometries revealed significant differences in comfort hours between variants by comparing enclosed space types and orientations. This confirms that the arrangement of rooms around the courtyard (and the light they receive) affects thermal outcomes. More extensive Xinjiang analyses also offer data-driven cladding solutions that enhance comfort while preserving the local language, by testing compressed earth and brick-wood cladding under current and projected climate conditions.

The courtyard is also part of the social infrastructure. The raised earthen supa platform, central to Uyghur domestic life, is used for hospitality, ceremonies, and daily relaxation, strengthening relationships between relatives and neighbors at the heart of the climate-controlled home. Design updates that protect the supa (with breathable surfaces and shaded edges) do not disrupt the social logic, while thermal improvements are made to the building’s exterior without being conspicuous.

The Lost Old City and Conservation Challenges

The large-scale demolition and reconstruction of Kaşgar’s Old City accelerated after 2009 and was officially framed as a disaster prevention program for unsafe housing in a seismically active region. International observers and academics documented the pace of demolition and warned of heritage loss and cultural erasure, while officials emphasized public safety following deadly regional earthquakes. The result was a profoundly altered urban fabric, where “heritage” was often recreated as themed street scenes.

Rights groups and researchers argued that the transformations in the Old City displaced residents and weakened the traditions of settled life in courtyard houses and neighborhood mosques, describing what some called “spatial massacre” or forced redevelopment. Reports and analyses detail how everyday domestic elements (including courtyards and supa platforms) are central to cultural memory and how their loss carries meaning beyond aesthetics.

Recent local regulations aim to protect the Ancient City and promote environmentally conscious tourism. For conservation to be credible, technical renovation work must be carried out in accordance with international heritage guidelines (wooden/connecting beams, joints, recycled reinforcement), and conservation policies must prioritize not only facades but also lived-in neighborhoods. In other words: keep people in place, repair what is fragile, document what is lost, and strengthen Kashgar against earthquakes without erasing the courtyard city that makes Kashgar what it is.

Isfahan: Axis, Gardens, and Grandeur

Maidan and Visual Choreography

Naqsh-e Jahan (Meidan-e Emam) is one of the world’s largest urban squares: measuring approximately 560 m x 160 m, surrounded by two-story arcaded galleries and flanked by different structures—the Imam (Shah) Mosque to the south, Ali Qapu Palace to the west, Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque to the east, and Qeysarie Gate to the north, which opens onto the bazaar. Built during the reign of Shah Abbas I, the square was used for polo, royal ceremonies, trade, and worship, and its architecture shaped the city’s daily life.

Since the long axis of the square is not aligned with the qibla, a dim, L-shaped entrance hall was used at the entrance of Sheikh Lotfollah to turn visitors toward Mecca. When you enter the shadow and turn, you emerge into a light-filled domed room. When the sun’s rays in the oculus form the tail of the bird painted in the center of the dome, the famous “peacock” effect emerges. This is spatial problem solving transformed into theater.

Isfahan Square demonstrates how to stratify public life: establish a clear framework (arched passageways), anchor corners with programs that attract different crowds, and direct flow using controlled perspectives and thresholds. These are transferable urban tools, whether you are designing a public square, a campus green space, or a retail center.

Caravanserais and Long-Distance Infrastructure

Safavid policy made transportation a design priority: roads, bridges, and caravanserais supported merchants from India to the Mediterranean. UNESCO’s newly inscribed serial heritage site, “Persian Caravanserais,” documents 54 examples across Iran. This system enabled long-distance trade and pilgrimage visits, and Shah Abbas expanded it further while rebuilding Isfahan as the capital.

Si-o-se-pol (Allahverdi Khan Bridge) terminates the Chahar Bagh axis and connects the Safavid center to the Armenian quarter of New Julfa; its double-arched passageways carry people, frame the views, and manage water from the Zayandeh Rud river. Iranica’s research emphasizes that Isfahan’s bridges served a triple function: hydraulic regulation, irrigation, and public entertainment. Thus, infrastructure transforms into civil architecture.

The Abbasid complex was originally a caravanserai established by the Safavid dynasty in the early 18th century. Today, this structure, which has been preserved in its redeveloped form as a heritage hotel, serves as a tangible reminder that roadside lodgings once financed schools in the Isfahan network and served traffic. This is an example of modern reuse that maintains the courtyard-caravanserai type in public life.

Geometry, Light, and Symbolic Architecture

Safavid architects popularized haft-rang (seven-colored) tilework, achieved by firing glazed, painted tiles together. This made it possible to read large-scale calligraphy and arabesques on curved domes and iwans. While Sheikh Lotfollah and Imam Mosques showcase this technique, the city’s Jameh (Friday) Mosque is an example of the old four-iwan plan developed by the Safavids on a monumental scale.

In Isfahan’s mosques, daylight is arranged like a material: it enters in strips through grilles at drum level, reflects off the muqarnas, and spreads across the tiles, illuminating the sacred texts. Research on mosque lighting and Safavid symbolism reveals that these effects not only enhance visibility but also choreographically regulate mood, ritual focus, and a sense of order.

Even the palace contributes to this: the Music Room at Ali Qapu uses carved plaster cuts and muqarnas to diffuse sound and reduce echo; this is an early acoustic diffuser embedded in the decoration. This reminds us that the word “sublime” carries a very sensory meaning here: a meaning designed around the interplay of geometry, light, and sound.

Architectural Lessons from the Silk Road

Connection as a Design Principle

The Silk Roads were never a single route, but rather a network of corridors comprising capitals, castles, passes, religious sites, and trading cities. UNESCO’s corridor nominations formalize this network logic: the Chang’an-Tianshan route connects 33 component areas over 5,000 km, while the Zarafshan-Karakum Corridor links mountains, oases, and desert passes into a single east-west backbone. From an urban planning perspective, these corridors demonstrate how the arrangement of places forms a readable region rather than isolated symbols.

Persian caravanserais functioned like recurring service stations along long-distance routes—secure courtyards with water, storage, stables, and rooms, spaced about a day’s journey apart. UNESCO’s serial list and ICOMOS assessment clearly define these as road infrastructure integrated into a larger network — proof that architecture can make connectivity functional on a regional scale. Today, transit corridors can borrow this rhythm: reliable, programmatically rich stops that set the pace of movement and trade.

The Silk Roads thematic study proposes viewing trade routes as families of site types (passages, warehouses, markets, ritual nodes). For designers, this means creating campuses, coastlines, or cultural zones not as one-off symbols, but as interconnected constellations (with clear boundaries, repeatable opportunities, and memorable thresholds).

Cultural Change and Hybrid Typologies

The Great Mosque in Xi’an aligns its prayer hall towards Mecca, yet employs Chinese-style wooden courtyard architecture (eaves, entrance gates, and axial courtyards), creating a structure that is both locally rooted in its construction and sensitive in its worship function. This represents a respectful adaptation model: function and orientation are preserved; form and details are translated.

UNESCO defines the Silk Roads as engines of idea exchange—languages, crafts, technologies, and religions moved alongside goods. Markets, madrasas, pagodas, mosques, bridges, and warehouses became shared “interfaces” where forms were copied, modified, and reassembled. Today, approach civic programs in the same way: bring together different uses (learning + trade; ritual + market) to make exchange visible and part of daily life.

Instead of mass imitation, combine elements at the component level (roofs, portals, curtains, courtyards), so that local architecture, climate, and regulations remain the primary principles, while foreign references enrich legibility. (Consider hybrid plans, local materials, and culturally specific ornamentation transformed into new, site-appropriate types.)

Resilience, Adaptability, and Local Resources

Along the roads, builders worked with materials that were slow to move or locally sourced: earth, brick, timber. Earth and stone working traditions are not “primitive”; they are optimized for climate, cost, and maintenance, and carry a craft heritage worth preserving. Conservation organizations such as ICOMOS and the Getty programs emphasize that preserving these systems sustains both knowledge and identity.

For fragile soil or unreinforced walls, low-tech measures (continuous tie beams, wall-to-roof connections, and stitching along corners and openings) significantly enhance life safety without compromising character. Getty’s Seismic Retrofit study packages these techniques, making them implementable by local builders and acceptable to regulators. Make resilience not just an engineering drawing, but a community skill.

Courtyards in hot and dry cities provide passive cooling: heavy paving buffers heat; shaded voids facilitate air movement; vegetation and water increase comfort hours. Recent research on courtyard geometry and ventilation has quantitatively measured these effects. Use these measurements to determine courtyard dimensions, adjust their orientation, and regulate day-night openings in contemporary residential and campus plans.