The design of housing and common spaces profoundly shapes the way communities interact, reflecting both cultural values and environmental constraints. From the courtyard-centred layouts of southern Europe to the vertical social spaces of North America and the compact micro-gardens of East Asia, architectural traditions and urban planning strategies in different regions create different opportunities for social connection.

Regional Differences

Southern Europe

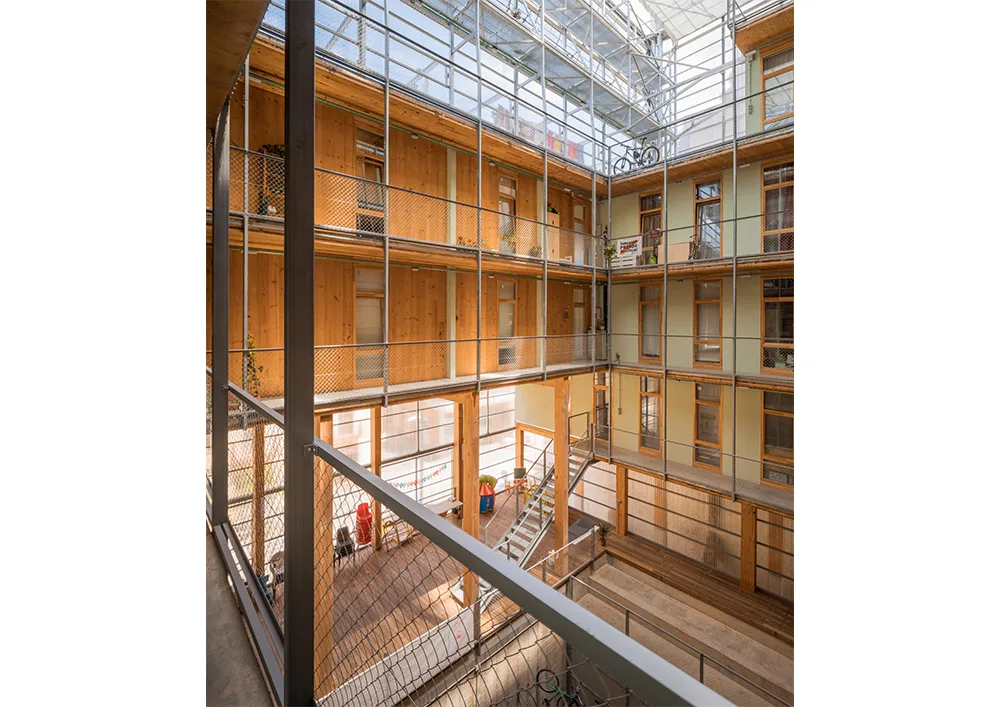

In places like Spain and Italy, warm climates and social traditions have long favoured courtyard-centred housing. Barcelona’s new La Borda co-operative, for example, surrounds 28 units with an open central courtyard and shared roof terraces. This reflects older typologies: Mid-20th century Italian social housing (e.g. Rome’s INA-Tuscolano project) used 6-8 storey blocks around internal gardens, integrating schools and shops in the same blocks.

Even in the early 20th century, historic Greek neighbourhoods such as Nikea built small 35 m² apartments around communal courtyard areas (with communal laundries and children’s playgrounds). These courtyards naturally cool the buildings and serve as semi-public foyers for residents, encouraging neighbourly interaction and communal activities (gardening, children’s games, evening gatherings).

North America

In North America, by contrast, social space is often pushed vertically or towards the front of buildings. High-rise or mid-rise housing in cities such as New York often compensates for limited floor space with communal roof decks and terraces. For example, the Via Verde residences in the Bronx offer community gardens on the rooftop and a central courtyard with a lounge on the top floor, as well as a playground and amphitheatre. All these amenities are open to every resident, reflecting the developers’ emphasis on “social sustainability” through shared spaces.

Similarly, traditional row houses in the USA use the front landing as a semi-public extension of the house. Jane Jacobs noted that brownstone landings (raised entry steps) function as a “neighbourhood amphitheatre” where neighbours meet and watch street life. American design culture tends to reward individual privacy (through setbacks, private courtyards or secure entrances) and often treats common spaces as add-on amenities rather than intrinsic to the layout of the block.

East Asia

Dense cities like Tokyo have to make do with a minimum of open space. Apartments often have only narrow balconies, which architects use as “micro-gardens”. For example, a project in Tokyo states that balconies do not count towards floor area, so each unit has a small planted terrace. These small balconies (like Japan’s traditional engawa patio) blur indoor/outdoor boundaries, but in practice serve more for personal use (drying laundry, flower pots) than for group socialising.

Yet communal spaces are emerging: Many towers in Asia include communal sky gardens or rooftop decks to escape the crowded city. Building regulations shape all of this: Tokyo’s allowance of balconies encourages green facades, while NYC requires stairs/elevators to access the roof and influences how terraces are designed. Cultural attitudes are also important. In some societies privacy is extremely important: As observed in a study of Jordanian housing, “privacy is deeply embedded in cultural and religious values, and preventing family life from being seen from the outside” is dominant. Such norms mean that designers in these regions often restrict or heavily screen common areas. In contrast, Southern Europeans more readily accept shared courtyards and plazas in everyday life, reflecting a different neighbourly ethos.

Urban Morphology and Social Space Activation

Different block and street layouts create very different opportunities for random encounters. In Barcelona’s Eixample district, the regular grid with octagonal (“chamfered”) corners is clearly designed to open up intersections and improve visibility. Each block originally had a central courtyard and numerous light wells, and building heights were kept moderate so that all units received daylight. The ground floors were commercial (shops, cafes) and the upper floors were residential, creating a constant street activity.

Today Barcelona’s “superblock” (Superilla) initiative is built on this foundation: Groups of 3×3 original blocks are closed to traffic and the internal streets are transformed into pedestrian squares and cycle paths. The planners emphasise that facilities and public spaces should be within a 10-minute walk of residents to promote social cohesion. In fact, the Eixample model combines a fine-grained grid (maximising intersections and facades) with integrated mixed use, so that casual gatherings can take place at many nodes (shops, chamfered plazas, inner courtyards).

In perimeter block cities such as Berlin or Paris, buildings form solid edges around private courtyards. Berlin’s historic “Höfe” (courtyard blocks) illustrate this well: behind the street-facing apartment blocks are deep courtyards that were once divided by social class.

Today these inner courtyards often contain gardens, workshops, cafés and the like. As one author puts it, Berlin’s courtyards “contain apartments, offices, workshops, shops, stores, galleries, cafés and gardens… They pump energy into Berlin street life in a unique way”. In other words, these semi-private courtyards function as hidden mini plazas for the residents. Ground floor entrances and passages opening onto the street offer passers-by a glimpse of this inner life. The permeability of these blocks (open passageways versus controlled passageways) and the transparency of the facades (retail facades versus blank walls) greatly influence vitality. When internal passageways are open or at least visible, and internal balconies or galleries overlook communal gardens, people feel invited to linger or pass through, linking public and private spaces.

In contrast, open-plan or Modernist superblocks (think of Le Corbusier’s towers in a park or many post-war housing estates) tend to discourage spontaneous encounters. Here houses or towers are scattered with lawns or car parks between them; there is often no fine grid of streets and entrances may be hidden behind the landscape.

Jane Jacobs pointed out that such settlements lack the “short blocks, density of housing and variety of uses” necessary for street life. Without porosity or inviting thresholds, residents can interact only at planned nodes (playgrounds, community centres), not on every block. Recently, urban designers have responded by reintroducing plazas, pedestrian routes and localised ‘urban rooms’ into new developments. For example, many mixed-use projects now include deliberate gathering points: a plaza on the ground floor in a shopping complex, an inner courtyard in a block of flats or an ‘agora’ between buildings. Even inside buildings, designers are creating “vertical lobbies”: A redevelopment in the Netherlands added a multi-storey stairwell with wide steps for employees to meet each other on their way up.

In summary, grid patterns and masses that maximise intersections and edges (and provide a transition from the private home to the public street) encourage everyday social encounters, while isolating superblocks or gated blocks tend to suppress them.

Architectural Details Encouraging Encounters

At the building scale, certain elements can choreograph spontaneous gatherings by creating inviting stopping points and sightlines. Wide staircases are one example. In Evernote’s office, a large white ash-coloured staircase between floors is flanked by cushioned bench seats on the wide steps. This “wide staircase is equipped with cushioned step seating” and becomes a natural place for employees to sit and talk on the way. Similarly, the NeueHouse co-working space in NYC features a tiered “Spanish Steps” in the entrance lobby – concrete stairs that function as auditorium seating for informal work or events. By designing the stairs as stepped sofas or amphitheatres, the architects transform a passageway into a social hub with built-in stopping points and sightlines.

Open-air galleries and balconies also mobilise the community. In Lacaton & Vassal’s social housing renovations (France), they infused existing towers with generous glazed balconies and “winter gardens”. These doubled the living space of each apartment and created common edges where residents could mingle. As Lacaton explains, “good architecture is open to life” – by adding verandas rather than demolishing them, they provided tenants with flexible semi-open space that residents could adapt to (growing plants, chatting, drying laundry).

In traditional settings, the engawa exemplifies this: engawa is a wooden porch with a roof that extends the interior space towards the garden. It is literally “a space between indoors and outdoors”; neighbours can have tea here or enjoy the breeze. (See image below.) Such layered thresholds blur the private/public: one moves gradually from the house to the engawa and to the street, making casual greetings more natural.

Shape: A traditional Japanese engawa (veranda) extends the interior space outwards under the eaves, providing a space for relaxing and chatting comfortably all year round.

More broadly, layered thresholds – such as landings, porches or semi-open lobbies – invite moments of contact. When a building entrance is located between the street and the apartment (for example, on a townhouse landing or in a recessed lobby), passers-by and building occupants naturally collide. Even subtle devices such as projecting balconies or double-height corridors can create pauses: SANAA’s Rolex Learning Centre (EPFL) uses sweeping ramps and 14 glazed atriums instead of enclosed corridors.

These gently sloping pathways and “social space” courtyards allow people to easily cross paths on all levels. SANAA describes it as an “intimate public space” designed to “encourage informal encounters” throughout its fluid interior. In summary, the architects blur the lines between circulation and living space through wide steps, open galleries, mid-floor terraces or porches, creating opportunities for sightlines and spontaneous dialogue while respecting accessibility and user choice.